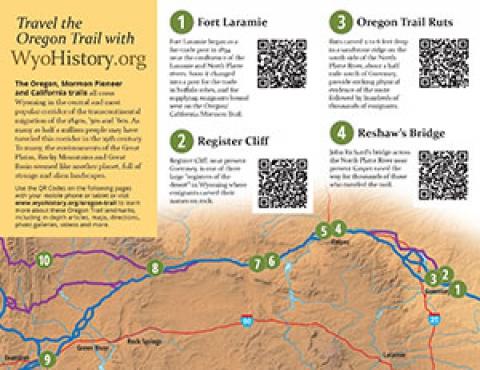

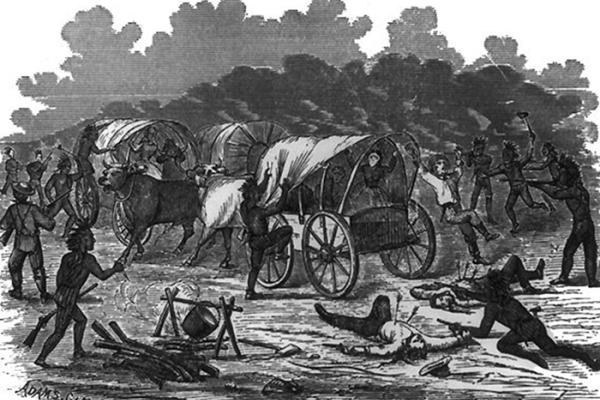

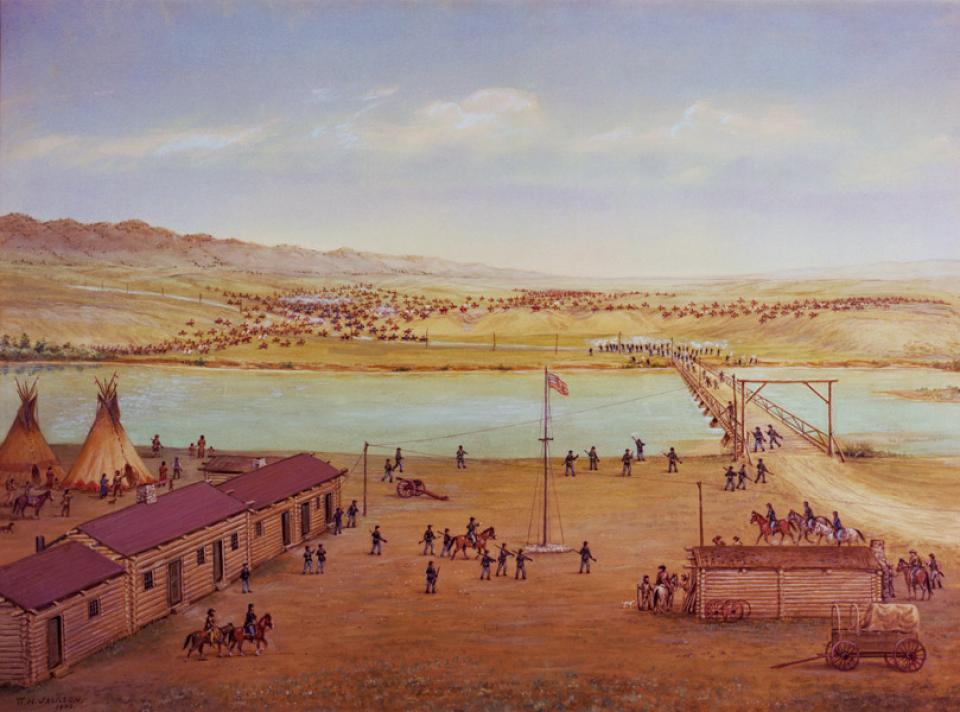

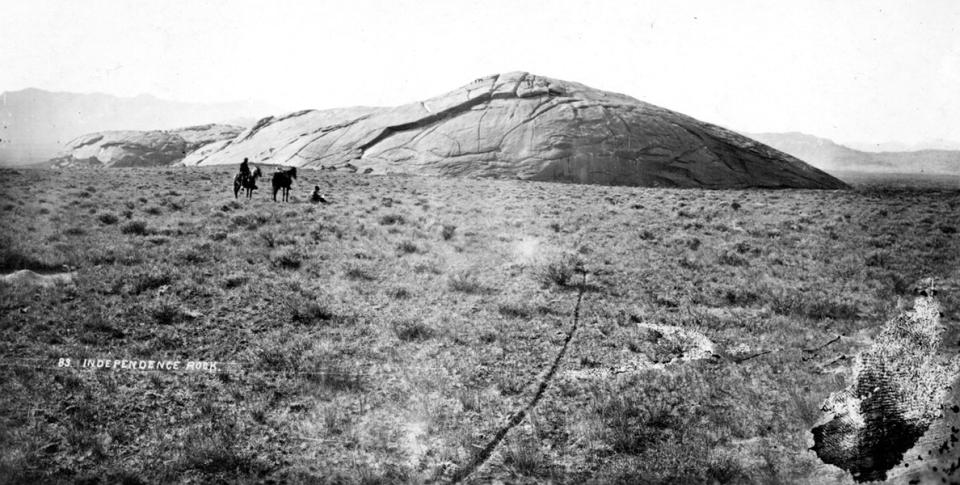

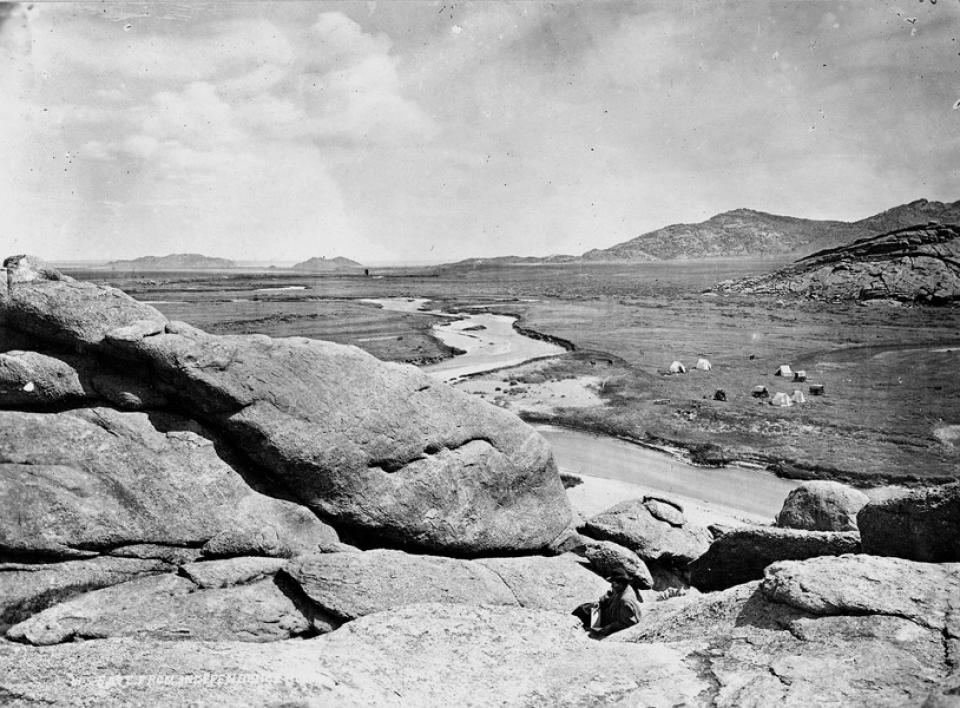

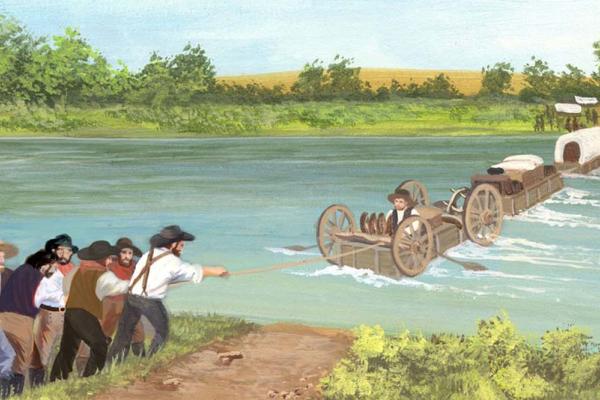

The Oregon, Mormon Pioneer and California trails all cross Wyoming in the central and most popular corridor of the transcontinental migration of the 1840s, ’50s and ’60s.

As many as half a million people may have traveled this corridor in the 19th century. To many, the environments of the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains and Great Basin seemed like another planet, full of strange and alien landscapes.

Use the QR Codes on the following pages with your mobile phone or tablet or visit www.wyohistory.org/oregon-trail to learn more about these Oregon Trail landmarks, including in-depth articles, maps, directions, photo galleries, videos and more.