- Home

- Encyclopedia

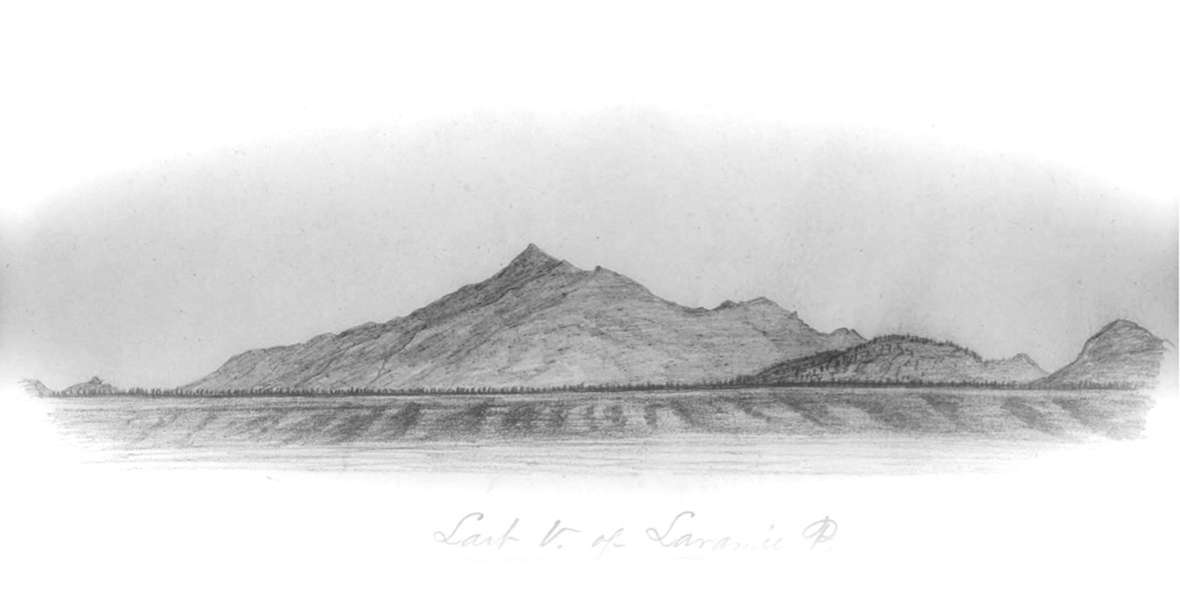

- Laramie Peak, Landmark On The Oregon Trail

Laramie Peak, Landmark on the Oregon Trail

Wagon-train emigrants got their first glimpse of the Rocky Mountains when, near Scotts Bluff in what’s now western Nebraska, Laramie Peak appeared on the horizon about 85 miles away.

A branch of the Oregon/California/Mormon Trail passed through Robidoux pass, a low opening south of the bluff. There, Antoine Robidoux, with his two American Indian wives and their families, kept a trading post and blacksmith shop. Many diarists noted Robidoux’s operation—along with the startling mountains dominated by a high, cone-shaped peak.

“Passed a blacksmith shop even it looks sociable in this wilderness, from tip of bluff. … I saw distinctly Laramie Peak and could distinguish the snow on its tops & sides, looks like a huge blue mound,” California-bound Peter Decker wrote late in May 1849—the first Gold Rush year.

“Passed this evening a trading house owned by a white man who has two Indian wives and several children,” Jackson Thomason wrote that June. “Some men can cut themselves off from the world and Society but I could not. After passing this trading house we crossed over a high ridge where I seen at a considerable distance Laramie’s Peak it being the first view of the Rocky Mountains to be seen.”

The West was changing now for the travelers, becoming drier and higher. The Platte and North Platte rivers, which they had followed through most of what’s now Nebraska and Wyoming, provided a broad, relatively level, natural roadway with ready supplies of water, forage and game.

“The scenery” from Scotts Bluff, Ansel McCall wrote in mid-June 1849, “is very beautiful, presenting to the view mountains, hills and valleys in every direction, changing the outlook entirely from that which we had been so long accustomed to, and convinced us that we were in reality approaching the Rocky Mountains, so long talked of. I do not know when I have witnessed a more beautiful sight.”

But on the western edge of the Great Plains, shortly after the emigrants passed Fort Laramie, the landscape began breaking up into a series of deepening ravines and pitched ascents. And many travelers were astonished, in late May or early June, to find the mountain still covered in snow.

“It is, at this day, covered with snow, which glitters in the sunshine like a diamond in the dark,” Dan Gelwicks wrote on May 28, 1849.

“We were at this point just opposite Laramie’s peak and near to it,” James Pritchard wrote about a week later, from the spot where the trail comes closest to the mountain that rose up about 20 miles to the southwest. “Its Snow caped summit seemed to peer to the Skys. Thus winter Stood aloft, in bold relief upon the left, beautifully reflecting the rays of the sun through the light fleeces of cloud that floated across the blue vault of heavens, while upon the right Nature was clad in all the soft, sweet, and gentle beauty of vernal bloom.”

But it was a cold spring. “Today has been a cold day throughout,” Charles Glass Gray wrote on June 13, 1849, “so as to make an overcoat, thick gloves, and flannels necessary. ... [N]o accidents occur’d though several threatenings of them, such as breaking axle trees and capsizing. For nearly all day we had a fine view of Laramie Peak from which I could not keep my eyes, render’d grander no doubt from our crawling along the prairies for so long a time and at night as it faded away I said to myself – All my troubles are forgot, gazing on this!”

But it was hard to avoid noticing the troubles of others, and hard sometimes, too, to believe one was seeing what one actually saw. “Passed several piles of baked beans and flour,” H.C. St. Clair wrote June 18, 1849. “One company throwed away 1.000 pounds of flour. We are in plain view of Laramie Peak. It appears to be 3 or 4 miles off but it is supposed to be 25 miles from the road and it is thought to be one mile high. There is something on it that looks white. Some think it is snow.”

While many emigrants found Laramie Peak awe-inspiring, the sight also dredged up anxiety as it signaled the beginning of their ascent into the mountains. From here on, the route would become more and more arduous. Laramie Peak would guide their journey for about a week. Although they would skirt the mountain itself, the peak was a towering presence that sometimes seemed to mock them as they struggled to ascend the more minor ridges nearby.

“We sometimes travel in the gorges between the hills and sometimes mount to summit when the prospect would be enchanting,” William North Steuben wrote June 15, 1849. “Right before us is Laramie Peak, one of the highest of the Rocky Mts most always in sight whether you are in the valley or on the hilltop. I cannot describe the Mts. they are so lofty, dark, rugged, dismal and hideous that they remind me of Nature in Chaos.”

Resources

Primary sources

- Decker, Peter. The Diaries of Peter Decker—Overland to California in 1849 and Life in the Mines, 1850–1851. Edited by Helen S. Griffen. Georgetown, Calif: The Talisman Press, 1966.

- Gelwicks, Daniel Webster. Diary kept by Daniel W. Gelwicks from Belleville, Illinois to the South Pass, in 1849. Typescript of MSS 71/161 c, Carton 24, Folder 2, Dale Lowell Morgan Papers, Bancroft Library.

- Gray, Charles Glass. Off at Sunrise: The Overland Journal of Charles Glass Gray [1849]. Edited by Thomas D. Clark. San Marino, Calif: The Huntington Library, 1976.

- McCall, Ansel J. The Great California Trail in 1849: Wayside Notes of an Argonaut. Bath, N.Y: Steuben Courier Printing, 1882.

- Pritchard, James A. The Overland Diary of James A. Pritchard, from Kentucky to California in 1849. Edited by Dale L. Morgan. Denver, Colo: Fred A. Rosenstock and The Old West Publishing Company, 1959.

- St. Clair, H. C. “Journal of a Tour to California [1849].” WA MSS S-1449, Beinecke Library. Typescript.

- Steuben, William N. “Memorandum Books 1849 Journal,” transcribed and edited by Harry Rutledge. Hayward, California, 1960.

- Thomason, Jackson. From Mississippi to California: Jackson Thomason’s 1849 Overland Journal. Edited by Michael D. Heaston, Introduction by Martin Harris. Austin, Texas: Jenkins Publishing Company, 1978.

Secondary sources

- Brown, Randy. Oregon-California Trails Association. WyoHistory.org offers special thanks to this historian for providing the diary entries used in this article.

- National Park Service. “Robidoux Pass,” Scotts Bluff, Nebraska, Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary. Accessed Jan. 9, 2017, at https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/scotts_bluff/robidoux_pass.html.

Illustrations

- The 1851 William Quesenbury sketch of Laramie Peak is from the collections of the Nebraska State Historical Society. Used with permission and thanks.

- The other two photos are by trails historian Randy Brown of Douglas, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.