- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Fort Bridger

Fort Bridger

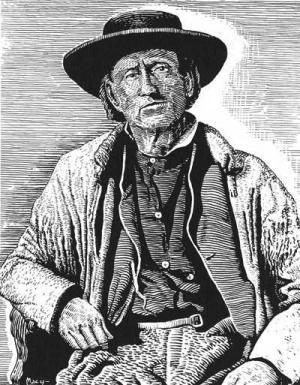

Noted frontiersman Jim Bridger and his partner, Louis Vasquez, established Fort Bridger in 1843 to service emigrant traffic. For the next century, the area—known as the Bridger Valley—served as a crossroads for the Oregon/California Trail, the Mormon Trail, the Pony Express Route, the Transcontinental Railroad and the Lincoln Highway. Today, the valley in southwestern Wyoming is a historic byway, incorporating the small towns of Fort Bridger, Urie, Mountain View and Lyman, which were bypassed when Interstate 80 was built.

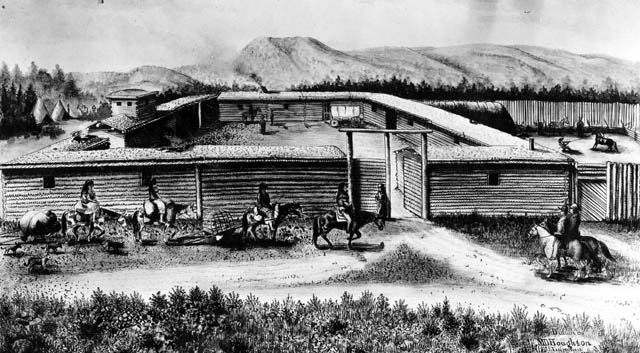

The most notable historic resource in the Bridger Valley remains old Fort Bridger, now operated as a state historic site. Bridger and Vasquez established the fort on the Blacks Fork of the Green River and planned to trade both with the American Indians they had befriended during their years in the fur trade and the westward-bound emigrants. Their first "fort" consisted of two rude double-log houses about 40 feet in length, joined with a pen for horses. They also boasted a blacksmith's shop, something that many emigrants welcomed after months on the trails.

But, for those emigrants who had long looked forward to their arrival at Fort Bridger, the post often turned out to be a disappointment. It was not nearly as well outfitted as the seemingly luxurious Fort Laramie on the eastern Wyoming plains. Fort Bridger turned out to be little more than a crude collection of rough-hewn log buildings. Emigrant Edwin Bryant said of the fort: "The buildings are two or three miserable cabins, rudely constructed and bearing but a faint resemblance to habitable houses.”

The Mormon Pioneer Company arrived at the fort on July 7, 1847. They spent a day there, but found all the prices very inflated. When a small group of Mormons settled nearby, tensions began to mount between Bridger and the new settlers. The settlers reported that Bridger was selling liquor and ammunition to the Indians, in violation of federal law.

Brigham Young, president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and a federal Indian agent, responded by sending the Mormon militia to the fort in 1853. Bridger learned they were coming and fled before the Mormons arrived. Later that year, the Mormons established Fort Supply about twelve miles south of Fort Bridger, specifically to service the Mormon emigrants.

Bridger complained to Gen. B. F. Butler, a U.S. senator, claiming the Mormons had robbed him of over $100,000 in goods and supplies and threatened him with death. The next spring, Young sent a detachment of well-armed Mormons to take control of both Fort Bridger and the Green River ferries, both of which became integral parts of the Mormon settlement plans for the region. The Mormons built a large stone wall around the fort.

The Mormons controlled the fort for a year, until July 1855, when Bridger returned. They asked him to sell but, seeing the new improvements, Bridger balked. After several months, he finally agreed. But the tensions for the Mormons were far from over. The fort again became embroiled in controversy in the fall of 1857 when President Buchanan sent U.S. Troops to Utah Territory to enforce federal authority and to install federally appointed territorial officers. The move became known as the Utah War, and followed years of tension between the Mormons and the federal government over questions of sovereignty, polygamy, land rights, water rights and the authority of courts.

The U.S. Army, under the command of Col. Albert Sidney Johnston, planned to use Fort Bridger as a base of operations for the march into Utah. But, before they could seize the fort, Mormon militia under "Wild Bill" Hickman and his brother burned it and Fort Supply. As a result, Johnston's army spent a miserable winter with little shelter and food.

That winter the Army established the temporary Camp Scott a mile or two to the south of the burnt fort, and in the spring of 1858, tension between the Mormons and the U.S. military subsided. The Army took over and rebuilt Fort Bridger to as a base for troops whose later jobs included protecting laborers on the transcontinental railroad, gold miners at South Pass and Shoshone Indians near the fort and later after their reservation was established on Wind River.

When the Utah War ended, the U.S. government refused to honor either Bridger's or the Mormons' claim to the property and instead turned the commercial parts of its operation over to William Alexander Carter, who had come west with Johnston's army as a sutler. Along with his family, Carter lived at the fort, rebuilding and stocking it and eventually becoming Wyoming's first millionaire.

Various volunteer units of the U.S. Army were stationed at the post during the Civil War. Beginning in 1866, the post was manned by regular units of the U.S. Army until 1878, when it was temporarily abandoned. The Army again occupied it from 1880 to 1890, when, with the end of the Indian Wars the Army closed it for a final time. Many of its buildings were sold and dismantled.

The 38-acre site was named a Wyoming Historical Landmark and Museum in 1933. Parts of the stone wall constructed by the Mormons in the 1850s have recently been the subject of archaeological explorations at Fort Bridger. Several historic buildings, which have been restored, remain at the fort, as well as a reconstructed trading post, an interpretive archaeological site and a museum housing artifacts from the different periods of Fort Bridger’s use.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Bryant, Edwin. What I Saw in California: Being the Journal of a Tour by the Emigrant Route and South Pass of the Rocky Mountains, across the Continent of North America, the Great Basin, and through California, in the Years 1846, 1847. New York, N.Y: D. Appleton & Co., 1848. Reprinted Palo Alto, Calif: Lewis Osborne, 1967. Kristin Johnson transcription.

- Carter, Edgar N. “Fort Bridger Days.” The Westerners Brand Book 1947. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Corral of Westerners International, 1947, 83–88.

- Carter, William A. Letterbook of W. A. Carter, Fort Bridger, Wyoming, 1860–1861. 17B-4-5, Columbia, Mo.: Missouri Historical Society.

- Fillmore, L. [Lemuel]. Diary, 1858. Special correspondent for the New York Herald for Kansas and the Utah War, 1858. Typescript, American Heritage Center. Copy in OCTA Manuscripts, Mattes Library. See also, [Lemuel Fillmore], Fort Laramie, 18 May 1858 and 19 to 29 May. In Gove, The Utah Expedition . . . and Special Correspondence of the New York Herald, 226–38; 249–60.

- Finlay, William Porter. “The Army for Utah.” Dispatches, July to September 1857, in Saint Louis Leader, 5 October, page 4, columns 3-4; 7 October, 4/3-4; 8 October, 4/2-3; and 27 October 1857, 2/2-3. Reprinted in MacKinnon, ed., At Sword’s Point: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858.

- Ferguson, Samuel Wragg. “With Albert Sidney Johnston’s Expedition to Utah, 1857.” Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 1911-12, 12, 303–12.

- Gove, Capt. Jesse A. The Utah Expedition, 1857–1858: Letters of Capt. Jesse A. Gove, 10th Inf., U.S.A., of Concord, N.H., to Mrs. Gove, and Special Correspondence of the New York Herald. Ed. by Otis G. Hammond. Concord, NH: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1928.

- Gove, Jesse Augustus. “March of the Utah Expedition from Fort Bridger to Fort Leavenworth, 1861.” WA MSS 226, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, Green Haven, Conn.

Secondary Sources

- Fifer, Barbara and Fred Pflughoft and David Morris, photographers. Wyoming’s Historic Forts. Helena, Mont.: Farcountry Press, 2002.

- Fort Bridger Historical Association. “Fort Bridger,” accessed 9/14/11 at http://www.forttours.com/pages/fortbridger.asp.

- Janin, Hunt. Fort Bridger, Wyoming: Trading Post for Indians, Mountain Men and Westward Migrants, Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Company, 2007.

- Moulton, Candy. Roadside History of Wyoming. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Publishing, 1995, 286-288.

- Wyomingheritage.org “Fort Bridger,” accessed 5/8/12 at http://www.wyomingheritage.org/fortBridger.html.

- Wyoming Tales and Trails. “Fort Bridger Photos.” Accessed Sept. 14, 2011, at http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/bridger.html.

- Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources. "Fort Bridger." Accessed August 21, 2013, at http://wyoparks.state.wy.us/Site/SiteInfo.aspx?siteID=17.

- Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources. "Fort Bridger Historic Site" brochure, with site map plus information on fort history, public events etc.accessed August 21, 2013 at http://wyoparks.state.wy.us/pdf/ft_bridger.pdf.

Illustrations

- The early drawing of Fort Bridger is from the Wyoming State Museum. Used with thanks.

- The drawing of Jim Bridger, after a photo, is from the National Park Service.

- The photo of Fort Bridger is from Wikipedia.

- In the photo gallery, the picture of the entrance sign at Fort Bridger is by Wyoming State Parks and Historic Sites. Used with thanks. The four photos of buildings at Fort Bridger are by Tom Rea.