- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Pony Express In Wyoming

The Pony Express in Wyoming

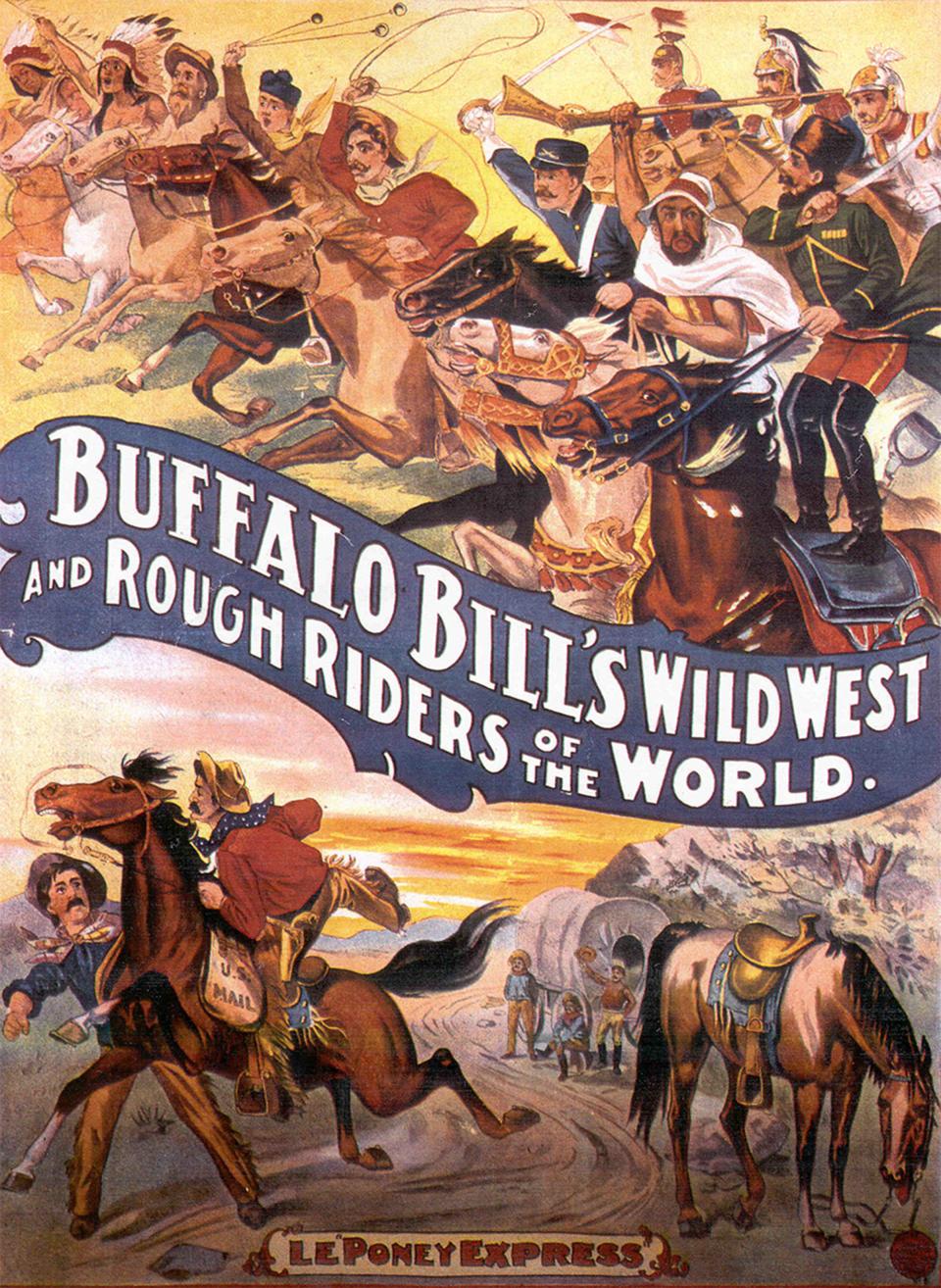

Wyoming played an outsized role in the history of the Pony Express. The world-famous Buffalo Bill Cody claimed to have been a Pony Express rider in Wyoming hired by Jack Slade, the most notorious figure associated with the Pony Express. Slade’s home base was at Horseshoe Creek, near present-day Orin, Wyoming. Buffalo Bill’s account of his time as a Pony Express rider is pure fiction, but were it not for Buffalo Bill and his Wild West show the Pony Express would have been no more than a historical footnote.

While Wyoming proved the backdrop for Buffalo Bill’s fictional exploits, the harsh Wyoming winter defeated the real-life Pony Express. The Pony Express was what we would call today a publicity stunt. Its sole purpose was to secure a $1 million U.S. Mail subsidy by demonstrating that mail could be delivered between the Missouri River and California on schedule even through winter. Despite claims to the contrary, however, the Pony Express could not do so. In the contest between the Pony Express and Wyoming winter, winter won.

Origin of the Pony Express

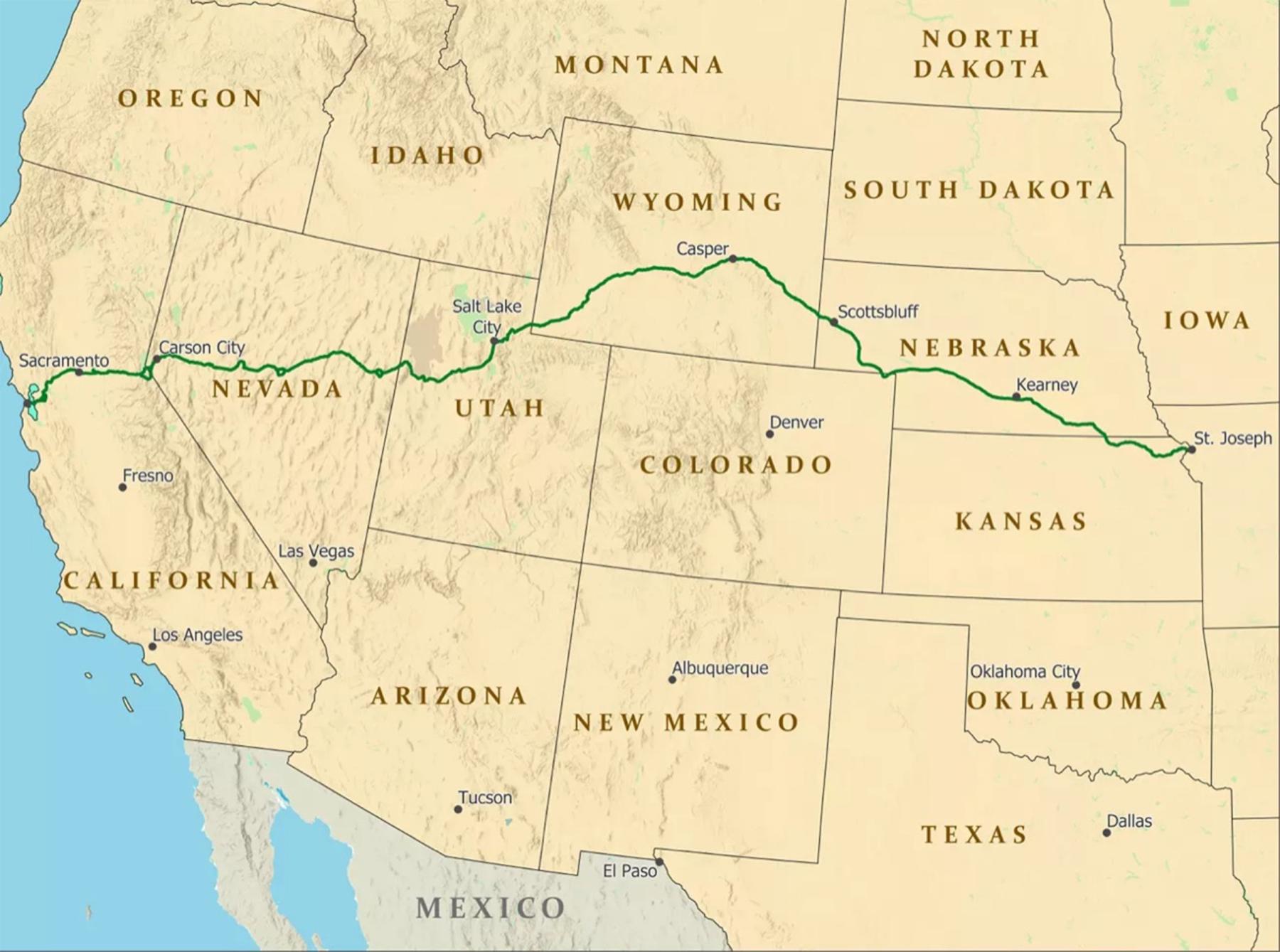

The Pony Express was a mail service that ran between St. Joseph, Missouri and Sacramento, California. The service advertised delivery in ten days, as compared to 20 to 30 days or longer for delivery by stagecoach or steamship. To achieve this pace, riders carried small loads of lightweight mail on horseback and changed horses at intervals averaging around fifteen miles. At the end of one rider’s route, the mail would be passed on to the next rider to continue it forward. The service operated from April 1860 to October 1861.

Image

The Pony Express was never organized as a separate company. Rather, it was a service operated by the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express (COC&PP). The COC&PP, in turn, was a subsidiary of the trans-Missouri freighting firm Russell, Majors & Waddell.

The end of the Mexican American War in February 1848 started the era of permanent U.S. military posts west of the Missouri River. These posts needed to be supplied by wagon train from the depot at Fort Leavenworth. At first, the U.S. War Department hired private freighters to haul government supplies. Over the next half-dozen years, William Russell and William Waddell, as partners, and Alexander Majors, operating on his own, were awarded army freighting contracts under this arrangement.

Starting in 1855, the U.S. War Department simplified the process by contracting with a single firm to service all forts west of the Missouri River. In order to win this lucrative contract, Russell and Waddell joined forces with Majors in December 1854 to create Russell, Majors & Waddell. In 1855, the army awarded the firm a two-year contract, giving it a monopoly on transporting all military supplies west of the Missouri.

The firm kept largely to military freighting until fall 1859, when two of the partners, Alexander Majors and William Waddell, reluctantly agreed to purchase the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company (L&PPE), a failing stagecoach and mail company started by the firm’s third partner, William Russell. Russell had gone to his freighting partners in late 1858 to propose they launch a stagecoach company to offer transportation to the newly discovered Pike’s Peak Gold Rush area near modern-day Denver, Colorado.

Majors and Waddell refused, arguing that the prospect was too risky. Unlike his more conservative partners, Russell wasn’t averse to taking big chances, especially if he could do so with borrowed money. Over time he acquired a reputation as a “plunger;” that is, a risk taker, a reckless gambler, a speculator. Rather than forego his plan, Russell instead partnered with John Jones to start the L&PPE. Russell and Jones borrowed heavily, relying in large part on Russell’s status as a principal of Russell, Majors & Waddell.

Six months later, in October 1859, the L&PPE collapsed. Majors and Waddell felt their firm had no choice but to purchase the line in order to save Russell, Majors & Waddell’s credit standing. Shortly after the firm purchased the L&PPE, Russell incorporated the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express (COC&PP) to continue the L&PPE’s stagecoach and mail service. From that point on, Russell, Majors & Waddell, once a staid freighting company, was diversified into the financially riskier ventures of also carrying passengers and U.S. Mail.

Unlike his partners Majors and Waddell, William Russell saw the U.S. Mail contract as a financial opportunity. The U.S. Government had awarded mail contracts for delivery to Utah since 1848, and from there to California starting in 1851. Among the handful of trans-Missouri overland mail contracts, one stood out above all others. This was a six-year, $600,000 annual contract awarded to the Butterfield Overland Mail to deliver mail between the MIssissippi River and California. Russell set out to ensure that his COC&PP would usurp the Butterfield Overland contract when it came up for renewal in 1862, and further, would win an increased U.S. Mail subsidy of $1 million per year or more.

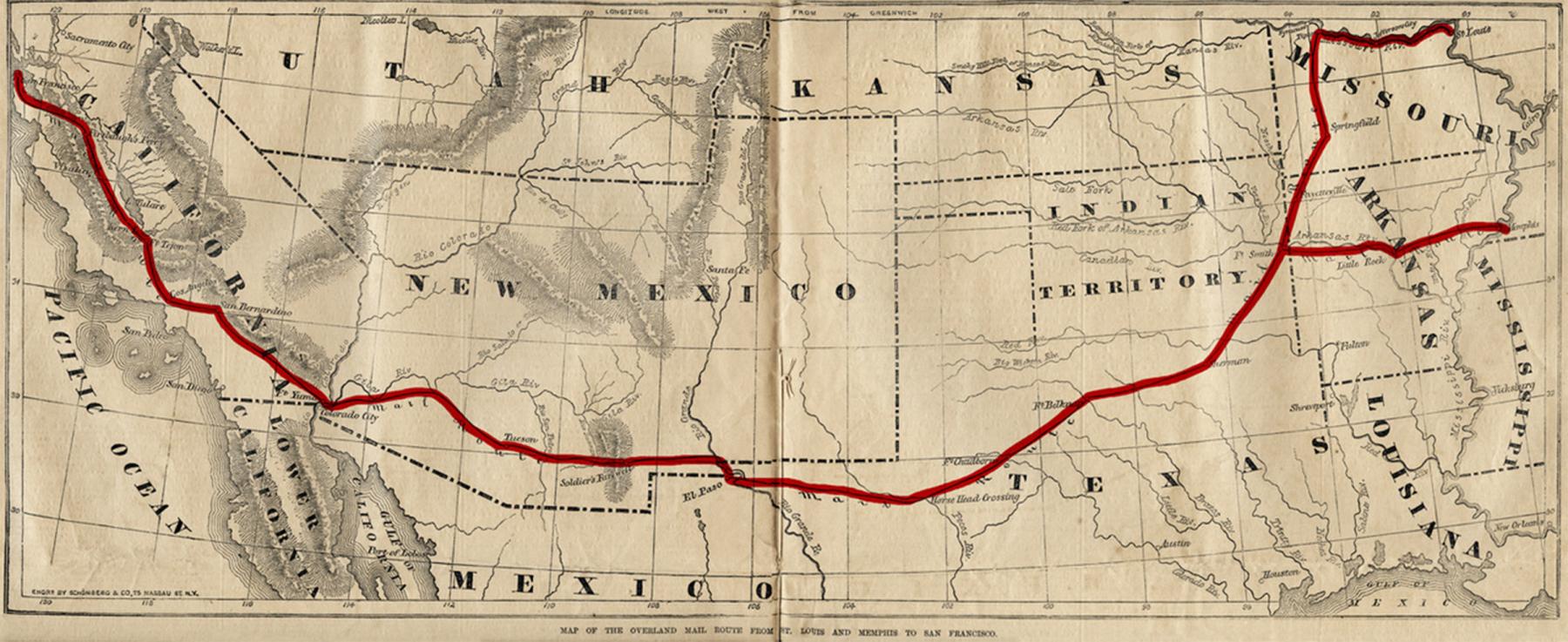

Mail contractors were required to use routes specified by the Postmaster General. The COC&PP contract to deliver mail to Salt Lake City required it use what became known as the Central Route: that is, the trail that ran up the North Platte and Sweetwater rivers and crossed the Continental Divide at South Pass, in what’s now south-central Wyoming. The Butterfield Overland contract specified it take the Southern Route: that is, through Guadalupe Pass along the border between the United States and Mexico.

The owners of the Butterfield Overland had not proposed that route. For one thing, the Southern Route was 2,800 miles long, nearly half again as long as the 1,950-mile Central Route through South Pass. But Postmaster General Aaron Brown forced the Butterfield Overland to use the Southern Route because up to that time no mail service had been able to keep a regular schedule over South Pass during the harsh Wyoming winters.

Common sense seemed to dictate that mail could be delivered more quickly over the shorter Central Route. The problem for Russell was how best to demonstrate he could provide consistent mail service year-round and in less time over the Central Route. He thought simply providing better service would not be enough. He felt he had to create something sensational to prove his point.

His answer was to create the Pony Express.

It is widely believed that Russell, Majors & Waddell started the Pony Express to save the Union by keeping California and its riches connected to the cash-starved United States on the eve of the Civil War. There is no support for such a claim. “Patriotic motives . . . had nothing to do with it,” historians Raymond and Mary Lund Settle have written. “The partners meant to faithfully render a needed public service, but in so doing they intended also to preserve their own legitimate business interests . . . Today it would be called an intensive national advertising campaign.”

Image

The Rise and Fall of the Pony Express

The Pony Express did create a sensation, especially in California where news was normally twenty to thirty days old. Unfortunately, the Pony failed to keep to its promise of delivering mail between St. Joseph and Sacramento in ten days. On the eve of the Pony’s first and only winter, Russell published a notice informing the public that after December 1 and throughout the winter, delivery time between St. Joseph and San Francisco would be extended to fifteen days. In fact, winter weather often doubled the advertised delivery time. The Pony Express, like every other mail service over the Central Route before it, could not maintain a regular schedule through the winter months.

Ironically, the iconic feature of the Pony Express—the lone rider racing across a wilderness on a swift horse—was the primary reason the service could not keep its schedule. A single pony, no matter how stout-hearted, could not plow through the deep Rocky Mountain snow. It needed a daily run of a team of animals to break the trail. Winter passage across the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California was just as difficult as it was over South Pass. But silver had been discovered near Virginia City, Nevada. As a result, the snow was often trampled down by mule teams traveling over the pass, easing the crossing. There was no such traffic to help the Pony Express through Wyoming.

The Pony Express was a money-losing proposition from the start. Historians estimate the service lost somewhere between $100,000 and $500,000 in 1860, or between about $3.6 million and $18 million today. It has also been estimated that it cost the firm sixteen dollars to move a single letter across the country, though the per-letter rates never topped five dollars.

Image

To stave off financial ruin, William Russell borrowed whatever he could under increasingly unfavorable terms. After he’d exhausted all other sources, he became involved in the embezzlement of government bonds, which he used as security for loans. In December 1860, the government official who loaned Russell the bonds had a crisis of conscience and confessed. On Christmas Eve, Russell was carted off to jail. And though the case against him was dismissed due to a technicality in February 1861, Russell, his partners, and their firm were thoroughly disgraced.

Just one month later, in March 1861, Congress did approve a $1 million contract for mail and stagecoach service over the Central Route. But rather than award it to the COC&PP, the contact went to the Butterfield Overland Mail.

During the months leading up to the Civil War (1861-1865), a group of rogue Texas Rangers pillaged and destroyed Butterfield Overland stations across their state, harassed passengers, and interfered with the mail. In order to maintain contact between California, with its wealth and with the headquarters of the Army of the Pacific, Congress ordered the Butterfield Overland to relocate over the Central Route. In order to expedite the move, the Butterfield Overland subcontracted with the COC&PP to operate the eastern half of the service, between the Missouri River and Salt Lake City.

The same legislation also dictated that a Pony Express stay in service until completion of the transcontinental telegraph line. The line was completed on October 24, 1861 and on that date the Pony Express winked out of existence, as if the switch that turned the telegraph on simultaneously turned the Pony Express off.

Myth of the Pony Express

There was nothing inherently special about the Pony Express. The idea of a fast horse-relay message line dates at least as far back as the fifth century BCE. The messages carried by the Pony Express did not directly affect U.S. history in any appreciable way. While the Pony Express brought important news to California on the eve of the Civil War, there is nothing to suggest that but for the Pony Express, California would not have helped elect Lincoln or would not have supported the United States against the Confederacy. To put it another way, there is nothing to indicate that California only stayed loyal because it received mail in ten days rather than eighteen or twenty by stagecoach.

Moreover, it accomplished none of the goals normally attributed to it. The risky venture helped ruin the largest freighting firm of the day, and erased whatever fortunes its owners had or might have amassed. So how did the Pony Express become such a symbol of the American West?

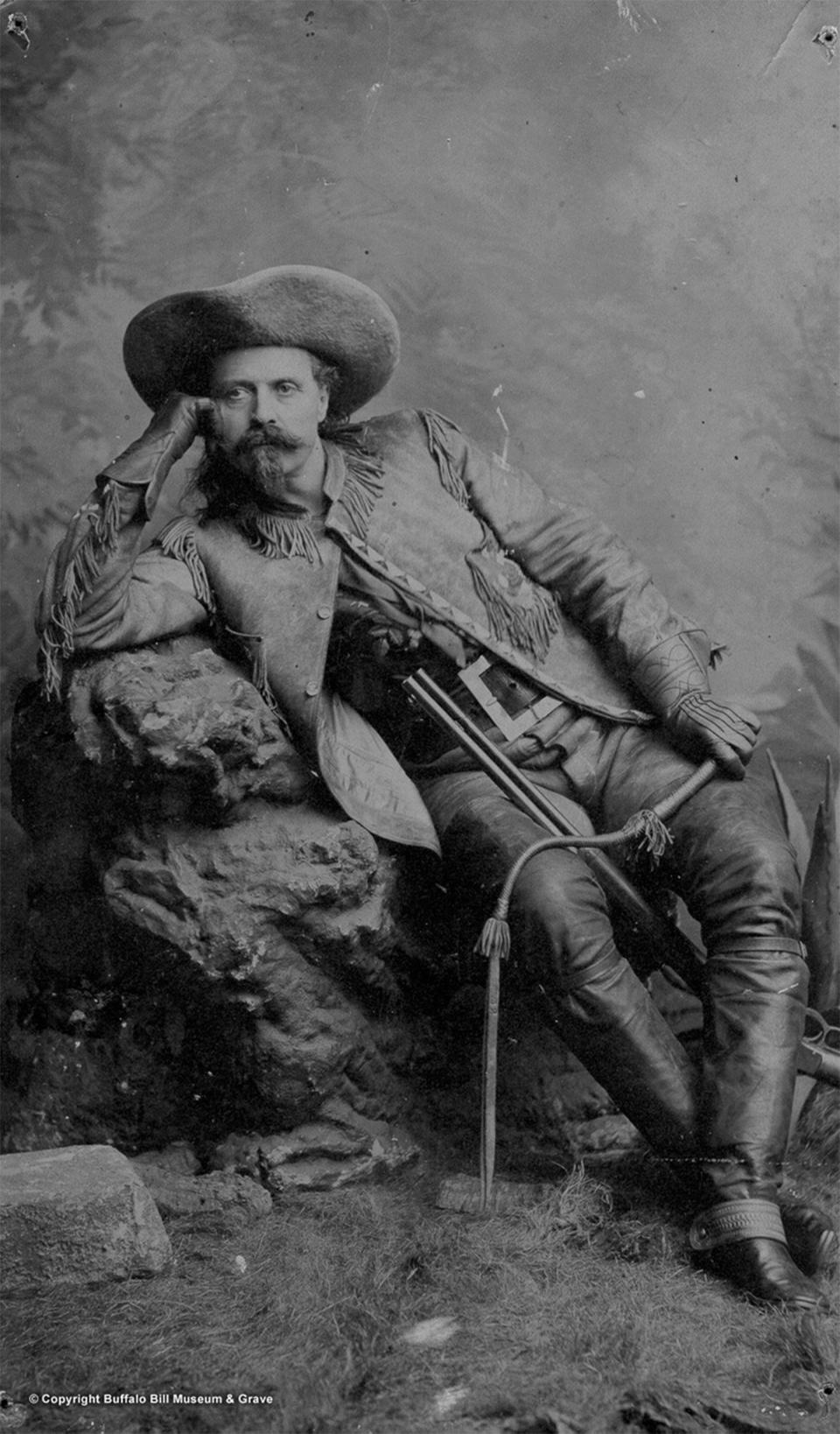

The primary reason is that Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, the most popular traveling show of the era, thrilled audiences throughout America and Europe for more than thirty years with its exhilarating Pony Express segment. A horseman would gallop down the bandstand, check his pony within one length, and just as quickly the mail bag would be on another pony galloping off at full speed. It was a showstopper. No one could ever forget it.

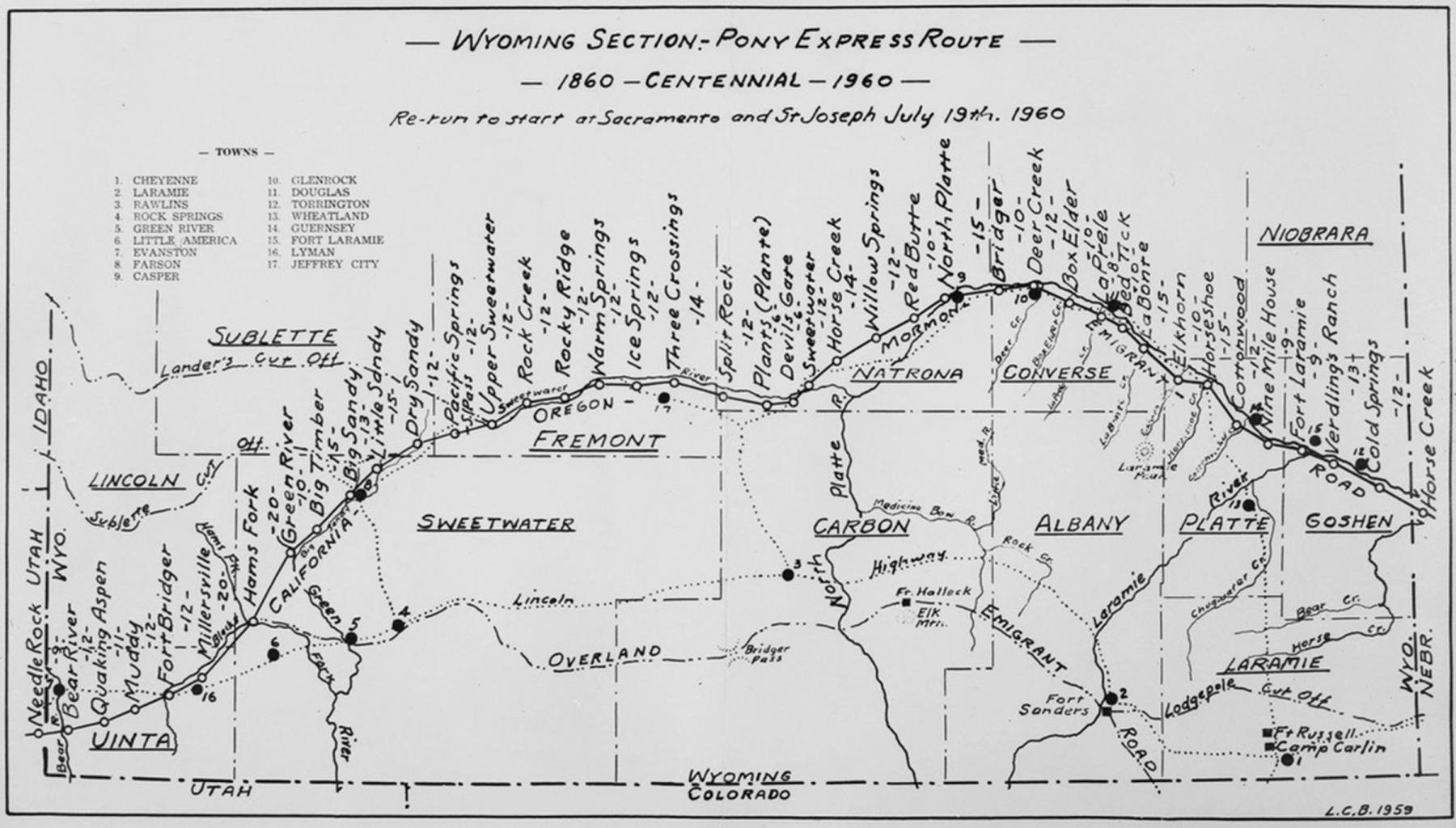

In his autobiography, Buffalo Bill Cody falsely claimed to have been a Pony Express rider, one of the most often repeated untruths about the Pony Express. He wrote that his route was a 76-mile run along the Sweetwater River between Red Buttes (near present-day Casper) and Three Crossings (near Jeffery City), and to have made one of the longest Pony Express runs, 322 miles. Buffalo Bill never rode for the Pony Express: the closest he came was to ride within a three-mile radius of Leavenworth, Kansas as a messenger for Russell, Majors & Waddell when he was eleven-years old. Nevertheless, Buffalo Bill Cody’s popularity, coupled with his fervid imagination and expert showmanship, spun that humble connection into one of the most memorable tales in U.S. history, the Pony Express as we know it today.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support which in part made this article possible.]

Resources

Sources

Books

- Corbett, Christopher. Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express. New York: Broadway Books, 2004.

- Godfrey, Anthony. Historic Resource Study: Pony Express National Historic Trail. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, 1994.

- Hafen, LeRoy R. The Overland Mail, 1849-1869: Promoter of Settlement, Precursor of Railroads. Reprint 2004. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1926.

- Settle, Raymond W., and Mary Lund Settle. Empire on Wheels. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1949.

- Settle, Raymond W, and Mary Lund Settle. Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga. New York: Bonanza Books, 1955.

- Warren, Louis S. Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Articles

- Gray, John S. “Fact Versus Fiction in the Kansas Boyhood of Buffalo Bill.” Kansas History 8, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 2–20.

- Rea, Tom. “Buffalo Bill and the Pony Express: Fame, Truth and Inventing the West.” WyoHistory.org, Sept. 8, 2015, accessed June 14, 2023 at https://wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/buffalo-bill-and-pony-express-fame-truth-and-inventing-west.

- Settle, Raymond W. “The Pony Express, Heroic Effort—Tragic End.” Utah Historical Quarterly 27, no. 2 (April 1959): 103–26.

- Settle, Raymond W, and Mary Lund Settle. “Origin of the Pony Express.” The Bulletin, Missouri Historical Society 26, no. 3 (April 1960): 199–212.

- Settle, Raymond W., and Mary Lund Settle. “The Early Careers of William Bradford Waddell and William Hepburn Russell: Frontier Capitalists.” Kansas Historical Quarterly 26, no. 4 (Winter 1960): 355–82.

- “The Pony Express Rides Again.” The Kansas Historical Quarterly 25, no. 4 (Winter 1959): 367–85.

Illustrations

- The map of the Pony Express route across the West is from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

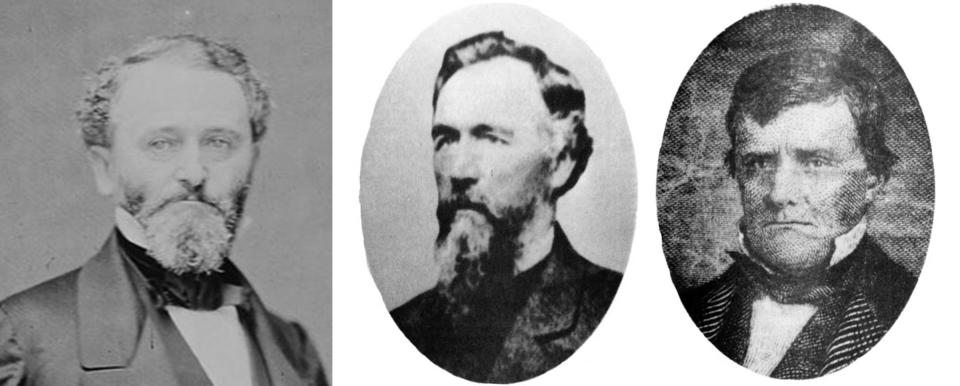

- The images of William Russell and Alexander Majors are from Wikipedia. Used with thanks. The photo of William Waddell is from the National Pony Express Memorial via a National Park Service historic resources study. Used with thanks.

- L.C. Bishop’s 1959 map of the Pony Express across Wyoming is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The image of William Henry Jackson’s painting of the Pony Express rider at Red Buttes is from the William Henry Jackson Collection at Scotts Bluff National Monument. Used with permission and thanks.

- The map of the Butterfield stage route and the Wild West show poster are both from the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum. Used with thanks.

- The portrait of Buffalo Bill in one of his show costumes is from the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Colorado. Used with thanks.