- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Buffalo Bill and The Pony Express: Fame, Truth ...

Buffalo Bill and the Pony Express: Fame, Truth and Inventing the West

Buffalo Bill Cody was just 14 years old, so the story goes, when he made his world-famous ride for the Pony Express. Leaving Red Buttes on the North Platte River near present-day Casper, Wyo., he galloped 76 miles west to Three Crossings on the Sweetwater River. His route took him along what we now call the Oregon/California/Mormon Trail. There was a station—at least a rough cabin and a horse corral—along the road every 12 miles or so. At each station, Buffalo Bill would have jumped off his sweaty horse and onto a fresh one.

As he dismounted, he drew the mochila—the leather saddle cover with special pockets for the mail—from the saddle, and threw it over the saddle of the horse the wrangler brought up. This happened in a matter of seconds. There was no time to lose.

The Pony Express began in the spring of 1860 and lasted for 19 months. Its purpose was to get the U.S. Mail across the country as fast as possible. California, a state since 1850, was filling up with white people. The forces that soon would lead to civil war were pulling the nation apart. If the United States was going to hold together, there had to be fast, reliable communication between the West Coast and the centers of power in the East.

When he arrived at Three Crossings, the story goes on, Buffalo Bill found that Miller, the rider who was to take over for him, had been killed the night before in a drunken brawl.

“I did not hesitate for a moment to undertake an extra ride of 85 miles to Rocky Ridge, and I arrived at the latter place on time,” Buffalo Bill remembered many years later. Rocky Ridge was near South Pass. There, another rider would have picked up the westbound mail young Bill delivered. But the eastbound mail needed a carrier, too, to take it back the way he had just come. Bill volunteered, again. When he got back to Three Crossings, the same man was, of course, still dead, and so Bill again transferred the mochila and galloped back to Red Buttes. The entire distance, supposedly, was 322 miles.

All in all, it was a thrilling ride, made by a valiant boy who was a great horseman all his life. By the time he was 50, in fact, Buffalo Bill was the most famous man in America. His Pony Express ride was one of the reasons for his stardom.

But Bill had things mixed up. For one thing, Three Crossings and Rocky Ridge are only 25 miles apart, not 85. For a second thing, much more important, he never did make the famous ride. In fact, William F. Cody never rode for the Pony Express at all.

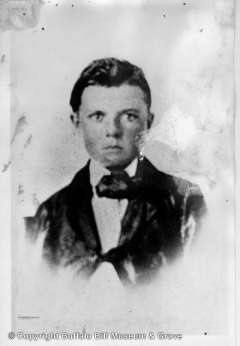

Young Will Cody

Young Will Cody was born in 1846 into a middle-class family on the Iowa frontier. After moving to Kansas in the 1850s, the family was thrust into poverty by the violence that then was leading up to the Civil War. Will Cody’s father, Isaac, was a surveyor, a founder of towns, a real-estate investor and a locator of land claims. During a dispute at a political meeting, a pro-slavery sympathizer stabbed him. Isaac Cody never recovered entirely from his wounds and died three years later. Young Will, meanwhile, had to find work to help support his mother and sisters.

When he was just 11 years old he took a job carrying messages on horseback for the freighting firm of Majors and Russell. He rode from the company’s offices in the town of Leavenworth to the telegraph office at Fort Leavenworth, three miles away.

Majors and Russell soon became Russell, Majors and Waddell, the largest transportation company in the West, which owned stagecoaches, thousands of freight wagons and tens of thousands of horses, oxen and mules to pull them, as well as a network of stations, corrals and employees across the West. This was the company that started the Pony Express system in 1860. Because young Will had worked for them briefly when he was 11, it may not have seemed to him such a stretch later to claim he had in fact ridden for the Pony Express when he was 14.

Will Cody’s real teenage years were troubling, not thrilling. When Congress made Kansas a territory in 1854, lawmakers left it up to the people there to decide whether to allow slavery. Armed men poured in. Some supported slavery, some opposed it. Elections were often violent. For a time, “bleeding Kansas,” as it was called, had two territorial legislatures. One supported slavery, one opposed it and each claimed to be the legal, rightful lawmaking body of the territory.

During the late 1850s, Will Cody did take jobs driving horses and wagons to places as far away as Fort Laramie and Denver. During the 19 months of 1860 and 1861, when the Pony Express was a going concern, he was in school in Leavenworth. He could not have been riding back and forth across what’s now central Wyoming at the same time, on the Sweetwater Division of the Pony Express.

A bloody border war

The Civil War broke out nationwide in April 1861. Sometime in 1862 young Will, consumed by a desire to avenge his father’s death, joined the Kansas Redlegs, an anti-slavery militia. These men and boys were not regular soldiers. They were unpaid and lived only on what they could steal, according to Louis Warren’s 2005 book, Buffalo Bill’s America, source of most of the biographical material in this article. Mostly the Redlegs stole horses and burned farms. More so even than other militias in Kansas and Missouri, they were criminals. They paid little attention to whether the families whose farms they burned were pro- or antislavery, or pro- or anti-union. Young Will Cody rode with them for about a year and a half.

Later in the war, he joined a regular Kansas regiment of the Union Army, and his soldiering became more respectable. After the war, he worked in western Kansas for a meat contractor that provided food for crews building the Kansas Pacific Railroad across the state. His job was to kill buffalo. He became known as Buffalo Bill, one of several hunters on the plains with that nickname at the time. He also became friends with a man who held various police jobs in the towns of western Kansas—James Butler Hickok, better known as Wild Bill. Hickok became suddenly famous in 1867, when a reporter wrote an article about him in Harper’s Weekly, a national magazine.

Soon, both Bills were the heroes of so-called dime novels. Authors of these cheaply made, pulp-paper books used Hickok’s and Cody’s real names but made up their thrilling adventures. Part of the fun for the readers was separating fact from fiction—guessing what was true in the stories and what wasn’t.

Cody understood this. By the early 1870s, Hickok, Cody, a friend named Texas Jack Omohundro, and Jack’s Italian-born wife, Giuseppina Morlacchi, were appearing together during the winters in stage plays around the West. Many of these they wrote themselves. The plays were full of scrapes, escapes, daring rides, fights, rescues, noble heroes and evil villains—the same kind of stuff that thrilled the dime-novel readers.

At the same time, the Indian wars on the plains were escalating. The U.S. Army always needed expert help to find its Indian enemies. Most of this work was done by other Indians and by mixed-race men. They were generally fluent at least in English and their mothers’ Indian languages, which made them useful as interpreters. But because of their race, the white officers were never entirely comfortable around them.

Cody was smart and friendly. The officers liked him because of this, because he liked to drink whiskey and tell stories and because he was white. But Cody also was comfortable around Indians in a way that most white officers were not. When it came time to chase Indian enemies, Cody stuck close to the Indian scouts and stayed out ahead of the troops. When the enemy was found, Cody could take the credit for the discovery.

Soon the officers were praising him in their official reports and in their conversations with newspaper reporters. And they passed his name along to rich men looking for a guide for hunting trips. When Gen. Philip Sheridan arranged for Grand Duke Alexis, son of the Czar of Russia, to come hunt buffalo in 1872, he made sure his favorite officer, George A. Custer, was along on the trip, and that Cody was the guide. At Sheridan’s suggestion, Cody persuaded Spotted Tail, chief of the Brule Lakotas, to visit the hunting camp in western Nebraska with a number of warriors and their families. To entertain the bigwigs, the Indians staged large dances and killed buffalo with bows and arrows from horseback. Custer and the duke were the stars of the event, but the newspapers noticed Cody, too: “He was seated on a spanking charger,” one columnist wrote, “and with his long hair and spangled buckskin suit he appeared in his true character of one feared and beloved by all for miles around.”

Fame

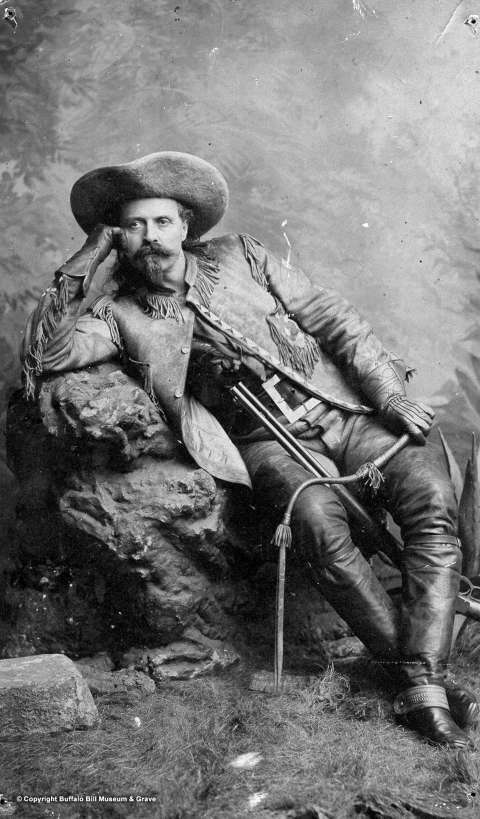

Cody was learning a lot about fame. He continued his double life, appearing in plays in the winter and scouting for the Army in the summers. He took part in a few skirmishes in the Indian wars, and they became part of his plays. Eventually, too, he wore his stage costumes when he went out on campaign. A few weeks after Custer’s defeat and death on the Little Bighorn in 1876, Cody was scouting with the 5th Cavalry in western Nebraska.

He was wearing a red shirt with billowing sleeves and silver-trimmed, black velvet trousers when he encountered a Cheyenne warrior named Yellow Hair. In the skirmish Cody killed him and scalped him on the spot. He sent Yellow Hair’s scalp, warbonnet, shield and weapons home to his wife, Louisa, by then living in Rochester, N.Y., where it was displayed in a store window. Newspapers covered the story. The following winter he toured with a new play, “The Red Right Hand; or, Buffalo Bill’s First Scalp for Custer,” implying that Cody’s was the first act of real revenge after the Custer fight.

In 1879, when he was 33 years old, Cody published his autobiography. The book smoothed the stories of his early life, and expanded his stock-driving jobs, supposed Pony Express service and Indian skirmishes into dramas of frontier nerve, pluck and progress. About this time, with the Indian wars on the plains all but over, with the buffalo nearly gone and the plains filling up with cattle, Cody must have realized that the demand for his scouting skills would only continue to shrink. But still, America was hungry for the other half of Cody’s skills—his skills in show business.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

In 1883, Cody and a partner named William "Doc" Carver put together a traveling show that was part pageant, part circus, part rodeo, part parade and part huge, open-air drama. It was built out of the same thrilling dime-novel and stage-play episodes Cody now knew as well as the episodes of his own life.

Versions of this show, known as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, ran for more than 30 years, from 1883 to 1916. All over North America and Europe, audiences loved it. In the earlier years, Cody found the most efficient way to make money was to park the show in a single spot near a large city—on Staten Island across the harbor from New York, for example, or in a 30-acre field outside Paris—and let the crowds come to him. In later years, after the show became well known, the production had to travel constantly to find audiences still new enough to want to pay to attend.

The show featured mounted Indians attacking a stagecoach or attacking a wagon train, and Indians attacking and burning a settler’s cabin, with the settlers rescued at the last minute by a band of mounted men led by Buffalo Bill. The company included as many as 650 people in the largest years—cowboys, Indians, buffalo soldiers, sharpshooters, trick riders and trick ropers, as well as cooks, wranglers, animal trainers and all the laborers needed to set up, take down and move the show.

Indians played themselves. In 1885, they included Sitting Bull, victor of the Little Bighorn. Other well-known chiefs and warriors took part over the years, too, among them Spotted Tail, Red Shirt and Standing Bear. The show even featured a pretend buffalo hunt.

Thanks to Buffalo Bill, all these events became central to America’s ideas—and the world's ideas—about how the West was settled. For decades after Cody’s death in 1917, they appeared and reappear still in Western novels and especially in Western movies. Year after year, and decade after decade, the show seemed thrillingly real to its audiences. “Down to its smallest details, the show is genuine,” Mark Twain, no stranger to the West, wrote to Cody in an unsolicited fan letter in 1884. The word “show” was never in the show’s actual title. It was called “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,” as though people could depend on it as the genuine article.

And year after year, decade after decade, the opening act was the one many found most thrilling of all: the Pony Express. A rider galloped at full speed to the grandstand and reined his pony back onto its haunches, front feet pawing the air. The rider leapt to the ground, lifted the mochila onto the next horse and was off again at a full gallop. The crowd was left breathless. Then people burst into cheers and applause.

In their luxurious, 10-in by 7-inch printed programs, audience members could read all about Buffalo Bill’s adventures. What did it matter if they were true or not? They seemed true. Cody’s genius lay in offering his audience what it needed to hear.

“Somehow,” writes Texas novelist Larry McMurtry, “Cody succeeded in taking a very few elements of western life—Indians, buffalo, stagecoach and his own superbly mounted self—and created an illusion that successfully stood for a reality that had been almost wholly different.”

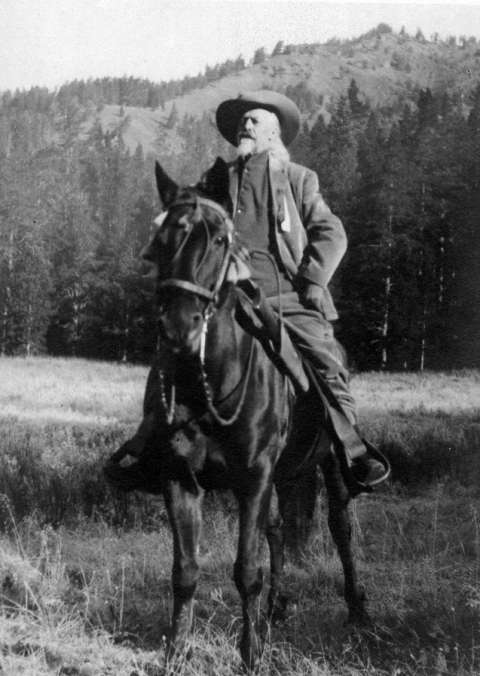

In the end, those realities caught up with the star of the spectacle. Cody’s debts were so large that he lost his show in 1913. He toured with other shows through 1916, but died broke, at his sister’s house in Denver, in 1917.

His legacy, however, is very much alive. Promoters in Wyoming and the West have since the turn of the last century used techniques that Cody taught the world. Cheyenne’s annual Frontier Days rodeo, still continuing today, was founded in 1897 partly with Cody’s Wild West in mind. “Let’s get up an old times day of some sort, we will call it ‘Frontier Day,’ Cheyenne Leader Editor E.A. Slack wrote that year. “We will get all the old timers together, have the remnant of the cow punchers come in with a bunch of wild horses, get out the old stage coaches, and some Indians, etc., and we will have a lively time of it!”

By the 1920s and 1930s, dime novels had given way to western movies. Tourists were driving regularly to Wyoming to see Yellowstone Park—and cowboys. Articles in the Cody Enterprise urged locals to dress western to supply the visitors with what they’d come to see, especially during the week of the Cody Stampede: “Get on the red shirt and top boots and help put ‘er on Wild. On June 1st the localities will be urged to don their eight-gallon hats and buckskin vests and ‘go western’ for the summer.”

That promotional tradition remains as strong as ever in Wyoming. “Roam Free,” the Wyoming Office of Tourism proclaims today at the top of its website. A large part of the West people come to roam—the imagined part, the part they most want to see—is the West that Buffalo Bill began showing us more than 125 years ago, when he let the world believe he really did make those thrilling rides for the Pony Express, right across central Wyoming.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Buffalo Bill. The Life of Hon. William F. Cody, Known as Buffalo Bill, the Famous Hunter, Scout, and Guide: an Autobiography. Hartford, Conn.: Frank E. Bliss, 1879. Republished in a facsimile edition, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978. Cody’s account of his supposed experiences with the Pony Express are on pages 90-92 and 103-125.

- Sherwood, Elmer. Buffalo Bill and the Pony Express. Racine, Wis.: Whitman Publishing, 1940. Accessed Aug. 21, 2015, at http://www.kellscraft.com/BuffaloBill/BuffaloBillcontentpage.html. A children’s book, and a great example of how the story gets retold.

Secondary Sources

- Gray, John S. “Fact Versus Fiction in the Kansas Boyhood of Buffalo Bill.” Kansas History vol. 8, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 2-20, accessed Sept. 4, 2015 at https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-history-spring-1985/15208. Some scholars had long been skeptical of Buffalo Bill’s Pony Express account, but Gray, in this highly detailed and thoughtful article, was the first to show that W. F. Cody never rode for the Pony Express at all.

- Hedren, Paul L. “The Contradictory Legacy of Buffalo Bill Cody’s First Scalp for Custer.”: The Magazine of Western History, Spring 2005. Accessed Sept. 4, 2015 via jstor at http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520671?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. This article is mostly about the art inspired over the years by Cody’s “duel” with Yellow Hair.

- McMurtry, Larry. The Colonel and Little Missie: Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley, and the Beginnings of Superstardom in America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005. A short, readable book by a master novelist who is affectionately tolerant of the foibles of his subjects. The quote about a “reality that had been almost wholly different” is on p. 138.

- Warren, Louis S. Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. The first full-fledged biography of Cody in 45 years and among the best in print. Warren leans on Gray (see above) in his conclusion that Cody never rode with the Pony Express.

For Further Reading and Research

- The website of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West is excellent, packed with information and links of all kinds. The site’s biographical page on William F. Cody is especially useful, though we would disagree with its remark that “at 15, he reportedly rode for the Pony Express.” Reportedly—yes, but not in fact. Of special interest are two You Tube conversations posted on the website between Cody biographer Louis S. Warren and Center of the West Curator of Public History John Rumm. Find them at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJxUSp72yx8 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtxTlwXzj54.

- For an unflattering, highly entertaining view of the Kansas Redlegs, watch the 1976 shoot-‘em-up The Outlaw Josey Wales, starring Clint Eastwood.

- The McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West maintains a rich storehouse of material related to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West—show programs, Cody’s correspondence, posters and much more.

- Sweetwater County Historical Museum. "The Pony Express," accessed April 15, 2020 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHyZerba1T4. Despite its claim that Buffalo Bill was among the riders, this is an excellent, concise five-minute You Tube video on the history and geography of the Pony Express in what's now Wyoming, with particular attention to the route through Sweetwater County.

Illustrations

- The image of the cover of Buffalo Bill and the Pony Express is from Kellscraft.com. Used with thanks.

- The photos of W.F. Cody at age 11, Buffalo Bill in his show costume, 1887 and W.F. Cody horseback near Pahaska Teepee in 1913 are from the great online photo archive of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Colorado. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Buntline, Buffalo Bill, Giuseppina Morlacchi and Texas Jack Omohundro is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.