- Home

- Encyclopedia

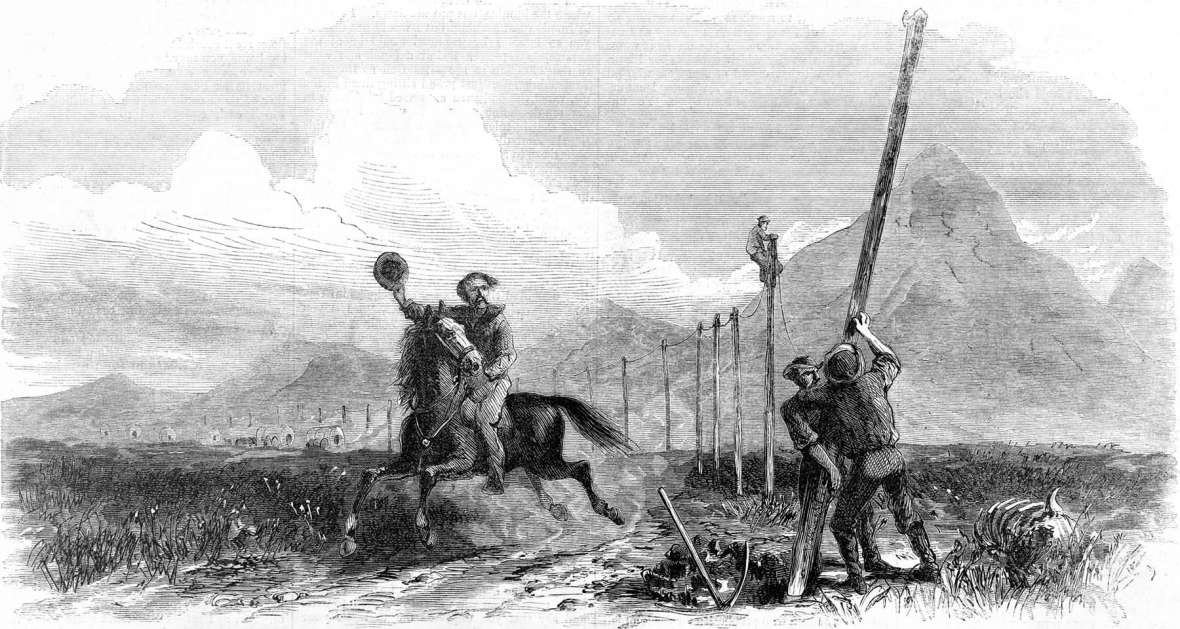

- The Telegraph Crosses Wyoming, 1861

The Telegraph Crosses Wyoming, 1861

Invented by Samuel F. B. Morse in the 1830s, the telegraph was already maturing when it crossed what soon became Wyoming in the 1860s. From the early days of settlement and through the railroad period, Wyomingites—and the nation—relied on it.

In 1861, the first transcontinental telegraph followed the route of the Oregon-California trail. Later, in May 1869, the main transcontinental telegraph line was shifted to the southern edge of the new Wyoming Territory, to run along the route of the Union Pacific Railroad.

The telegraph signaled the demise of previous methods of communication. Before then, a message could be delivered only as fast as a horse could run or a ship could sail. A message took 45 days by steamship from New York to San Francisco, and more than 20 days by overland stagecoach from St. Louis to San Francisco. The Pony Express took 11 days from St. Joseph, Mo., to Sacramento.

Just before the start of the Civil War, Congress offered a subsidy to any company agreeing to build the transcontinental telegraph. Western Union submitted a bid for $40,000 to build the entire line. In the winter of 1860-61, Edward Creighton surveyed the proposed route between Omaha and California to be built with the financial support of Western Union. He dug the first post hole for the telegraph line on July 2, 1861. (Creighton and his brother John were prominent Omaha merchants; their endowed local university still bears their name.)

Creighton, who during the construction phase became Western Union’s general agent, organized two teams of builders, one to work on the line from the West, the other from the East. The eastern line, built by a subcontractor named the Overland Telegraph Co., reached Fort Laramie on Aug. 5, 1861. On Oct. 18, 1861, the workers reached Salt Lake City, completing the eastern section of the line. The western section, shorter but covering more difficult terrain, was finished by the Pacific Telegraph Co., another subcontractor, on Oct. 24.

Some 27,000 poles were set every 75 yards over 1,086 miles from Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory, to Fort Churchill, Calif., in the four months it took for construction. Poles were to be found “en route—" not so easily accomplished on the treeless plains. Western end materials were shipped around Cape Horn to San Francisco.

Furnishing the poles for a short stretch of the Wyoming segment led to the first civil lawsuit ever decided by the Wyoming Supreme Court—the case of Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Monseau. The case finally reached the territory’s highest court in 1870. Monseau had contracted to furnish 754 telegraph poles at $2.50 each. Western Union claimed the man who made the deal with Monseau was not authorized to do it on the company’s behalf. The three-member Supreme Court upheld the lower court ruling in Monseau’s favor. (E. P. Johnson, for whom Johnson County, Wyo., would later be named, represented Monseau).

Galvanized iron wire “of the best quality” and insulators, iron holders embedded in glass and enclosed in wooden forms, kept the wires off the ground. Batteries, needed to power the signal, were shipped as powder in containers with electrodes. Water was added later to bring the batteries to charge.

Stations were located every 20 miles because batteries were usually only strong enough to relay to the next station. Some stations had once served (or were still serving) the overland stage lines. Each telegrapher sent off to the next station, etc., from these “relay stations.” Cost to send a message was $7 for 10 words, seemingly expensive, but cheaper and quicker than the Pony Express. Once the telegraph connected the United States, the Pony Express stopped running.

Eventually upstaged as a technological and engineering wonder by the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869, the telegraph line was completed on Oct. 24, 1861, to national acclaim. The Civil War had begun in April of that year. Just a few months after the war’s outbreak Stephen J. Field, chief justice of California and brother of Atlantic cable promoter Cyrus Field sent a message to Abraham Lincoln assuring him of California’s loyalty to the Union and promising that the telegraph line would “be the means of strengthening the attachment which binds both the East and the West to the Union.”

Through the Civil War years, Western Union, builders of the transcontinental line, continued to grow and prosper. By 1866, the year after the war’s end, the Western Union monopoly controlled a staggering 90% of the telegraph traffic in the United States. Congress tried to nationalize the telegraph and place it under the post office, but failed.

Western Union was challenged eventually by the telephone. By about 1890 telephone engineers expanded the range of audible conversations to a few hundred miles, culminating in the establishment of transcontinental telephone service in 1915.

That, combined with airmail service, radio communication, and teletypes in the 1920s and 1930s, brought about the telegraph’s decline. By 1990, all that remained of the once-dominant monopoly was its money transfer services. The internet, of course, has furthered even that decline.

(Editor’s note: Special thanks to the author, who recently rediscovered a draft of this article originally meant for his syndicated column, Buffalo Bones: Stories from Wyoming’s Past, which ran in Wyoming newspapers in the 1980s and 1990s.).

Resources

For further reading and research

- “Invention of the Telegraph” and “Impact of the Telegraph.” Samuel F. B. Morse Papers at the Library of Congress LOC: 1793-1919, accessed Nov. 20, 2021 at https://www.loc.gov/collections/samuel-morse-papers/articles-and-essays/collection-highlights/invention-of-the-telegraph/ and https://www.loc.gov/collections/samuel-morse-papers/articles-and-essays/collection-highlights/impact-of-the-telegraph/.

The second of these includes a great map of the network of telegraph stations in the United States and Canada in 1853. - Nonnenmacher, Tomas. “History of the U.S. Telegraph Industry.” EH.net, a publication of the Economic History Association, accessed Nov. 20, 2021 at https://eh.net/encyclopedia/history-of-the-u-s-telegraph-industry/. A brief yet thorough history of the business of telegraphy.

- Johnson, Hervey, and William E. Unrau (ed.). Tending the Talking Wire: A Buck Soldier’s View of Indian Country. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1979. Hervey Johnson came to present Wyoming with the 11th Ohio Cavalry in 1863 to guard the telegraph line. The 100 or so letters he wrote home to his mother and sisters make this book a superb primary source. The book is in many Wyoming libraries.

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: the Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-line Pioneers. New York: Walker Books, 1998.

- “Women Telegraph Operators in the Civil War.” Signal Corps Association, accessed Nov. 20, 2021 at http://www.civilwarsignals.org/pages/tele/pages/women.html. Details on the lives of five women telegraphers in the 1800s.

Illustrations

- The engraving of the Pony Express rider passing the telegraph-line builders was first published in Harper’s Weekly, Nov. 2, 1867 and is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the stump of a telegraph pole is by Jason Vlcan, of the staff at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.