- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Industry, Politics and Power: The Union Pacific...

Industry, Politics and Power: the Union Pacific in Wyoming

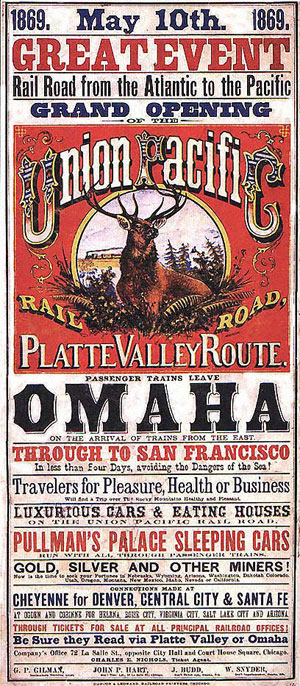

One of the most significant moments in Wyoming history didn’t occur within its borders. On May 10, 1869, a large crowd gathered at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, to celebrate the completion of the world’s first transcontinental railroad.

|

At the given signal, a hammer slammed down on a golden spike, sending an electric pulse out over telegraph lines stretching west to San Francisco, and east across Wyoming Territory to Omaha. The crowd cheered. They listened to speeches. They waved flags, toasted with champagne, and posed for photographs. In New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago thousands took to the streets to celebrate the joining of the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific Railroads.

For the sparsely populated Wyoming Territory, the golden spike meant the end of a prosperous two-year construction period brought by the Union Pacific. Yet in the wake of the boom, the railroad offered economic opportunities that simply didn’t exist during the emigrant trails era.

While hundreds of thousands crossed Wyoming by wagon train in the 1850s, most recognized that it was too high, too cold and too dry for rainfall-dependent farming. It also lacked profitable mines. Those factors meant that almost no travelers who crossed Wyoming by wagon train decided to stay.

The transcontinental railroad changed all of that by giving many more emigrants a means to live in Wyoming. Specifically, the rails provided a model of industrial development based on transportation of agricultural and mineral products. The railroad opened up trade to distant markets, spreading the costs of operating the line outside of the territory. That recipe worked well for the small population of the territory, and gave the Union Pacific tremendous influence on Wyoming’s politics and culture.

In some ways, the combination of transportation and resource extraction created by the Union Pacific continues to drive the Wyoming economy. The railroad also set up dynamics of political and economic power that persist even now. More than any other economic force, the Union Pacific Railroad shaped the Wyoming we know today.

The railroad creates the need for a territory

The building of the Union Pacific across Wyoming forever changed the political and physical landscape, not least by bringing about the organization of Wyoming Territory out of a huge piece of land lopped off the southwestern part of Dakota Territory.

The region needed its own government because of its remoteness from the capital of Dakota Territory at Yankton on the Missouri River. Wyoming Territory also took a small part of Utah and Idaho territory in the west of the continental divide. (The northern boundary of Wyoming Territory was defined by the organization of Montana Territory in 1864.)

When the UP first came to Wyoming in 1867, the railroad exerted a tremendous amount of influence on the government. Often it seemed that governments existed primarily to serve the interests of the railroad, first with federal military support to pacify Indians, unruly squatters or striking coal miners, and then by creating the structure of territorial government needed for conducting business.

In Gov. John A. Campbell's 1869 inaugural address to the Wyoming Territorial Legislature, he noted that, "For the first time in the history of our country, the organization of a territorial government was rendered necessary by the building of a railroad. Heretofore the railroad has been the follower instead of the pioneer of civilization."

As leaders of one of the largest private landholders and employers, UP executives made decisions that affected every town and impacted the wealth of Wyoming. Territorial officials fought for the right to tax property owned by the railroad and ultimately prevailed in an 1873 court case. After this, Wyoming Territory collected one-third of its property taxes from the UP right of way, track and rolling stock.

Congress creates the Union Pacific

For the company and the nation, the primary motivation for building a transcontinental railroad was to get to the Pacific Ocean. The idea for such a railroad first appeared in a pamphlet in 1832, but gained more credence with the signing of treaties that opened up trade with China and Japan, and with the 1849 gold rush to California. Merchants, migrants and miners wanted to speed the trip to California and Asia by avoiding the long ocean journeys via Cape Horn and the Isthmus of Panama.

In 1854, Congress created the Pacific Railroad Survey to study the viability of prospective train routes advocated by southern and northern states. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis sent out parties to identify routes at the 49th, 47th, 41st, 35th, and 32nd parallels. As a devoted southerner, Davis, who would later become the president of the Confederacy, preferred the southernmost route from New Orleans to California.

The 41st parallel report by Edward Beckwith built upon previous reconnaissance made by Howard Stansbury in 1851. On the advice of Jim Bridger, Stansbury had scouted Black’s Fork, Bitter Creek and a low pass over the southern Laramie Range via Lodgepole Creek and Crow Creek. In 1854, Beckwith identified Weber Canyon as a good route between the Green River Basin and the valley of the Great Salt Lake.

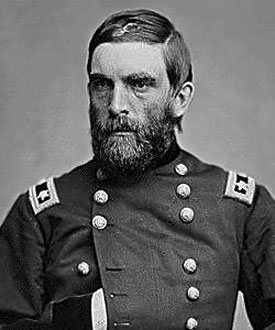

Many years later, Grenville Dodge, the chief engineer during construction of Union Pacific, claimed he discovered the pass over the Laramie Range in 1865 while being chased by a band of Indians. The story of the Indian chase is not substantiated by his journal entries from that day, but it does seem clear that he found the route that would become known as "the gangplank" for its even grade, and which Interstate 80 follows now from Cheyenne west to the summit of the Laramie Range.

The 41st parallel survey identified the route that would eventually be used by the Union Pacific. It offered both the shortest route west and the best crossing of the Rocky Mountains. But for the rest of the decade, railroad plans stalled because of tensions between North and South over whether and where slavery would be allowed to expand in the West.

The secession of the Confederacy at the opening of the Civil War allowed the remaining members of Congress to take action on a transcontinental railroad. President Abraham Lincoln chose a northern route for the railroad, with Council Bluffs, Iowa, on the east bank of the Missouri River as the terminus. Lincoln did so at least partially because Dodge, a Union general and railroad engineer, had in the late 1850s shown him maps of a prospective railroad following the Platte River across Nebraska.

Lincoln was a loyal supporter of railroad construction. After the reunification of the Union and the abolishment of slavery, President Lincoln’s other major policy goal was the establishment of a transcontinental railroad. He had seen how railroads developed his home state of Illinois, and railroads had been among his most important clients in his Springfield law practice. Californians started agitating for a railroad over the Sierra Nevada in the early 1860s, and Lincoln wanted to ensure that California would maintain its loyalties to the Union.

|

The federal government offers land and financing

Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act on July 1, 1862. The act created the Union Pacific, and subsidized the Union Pacific and already-existing Central Pacific railroads by granting 10 square-mile sections of land for each mile of track laid.

In 1864, a second Pacific Railroad Act drafted by Union Pacific attorneys doubled the land grant to 20 sections for each mile, which created a checkerboard of odd-numbered sections for 20 miles on each side of the line and amounted to 4,582,520 acres in Wyoming Territory. The grant also gave mineral rights under these lands to the railroad.

In addition, the government loaned the railroads $27 million, enough to cover half the cost of construction. The loan would last 30 years at a charge of six percent interest. The Union Pacific also sold $11 million of stock, and bonds totaling $30 million. Most of the investment came via financiers in New York who sold stock and bonds on the East Coast and in Europe. Investors included wealthy merchants from the China trade, Civil War financiers, and European nobility.

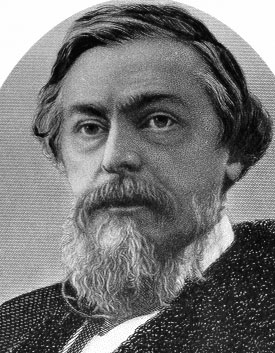

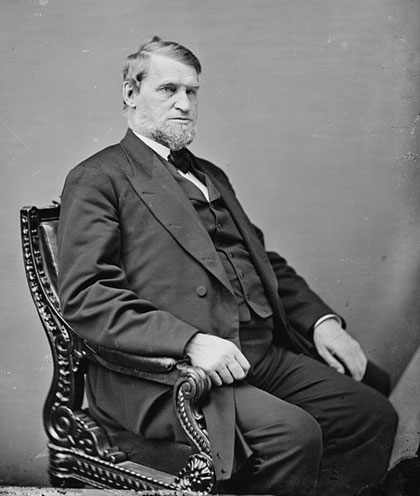

The chief financier and general manager of the Union Pacific was Thomas Durant, a vigorous self-promoter who seemed to care less about building railroads than earning money. Durant’s allies included Union Pacific President Oliver Ames and U.S. Representative Oakes Ames, two brothers from Boston who showered members of Congress with gifts of stock to gain favorable legal treatment for their line.

The paper value of Union Pacific stock far exceeded the actual capital valuation of the company, in part because the company sold its bonds on par, meaning an investor might buy a $10 bond for a discounted price of $6.30, the par value. This “watered stock” put shareholders at risk, since there was no guarantee their shares would ever reach the face value. Selling stock at par also made it difficult to pay back the government loans because companies didn’t have as much cash value as they claimed on the books. Such questionable financing, however, expedited construction.

The UP also fought territorial attempts to tax its land grant, which resulted in an 1875 ruling against the railroad on that question. The company surveyed its land very slowly to try to avoid taxation, and it didn't secure patents on land until interested buyers appeared.

The checkerboard pattern of ownership made few ranchers interested in purchasing the land, however, as they needed large, intact acreages to raise livestock in a dry climate. The UP floated a proposal to abandon the checkerboard by taking all the land within 20 miles on one side of the tracks and releasing all railroad land on the other side. The territorial government rejected the proposal in 1878, however, because it would create "endless confusion."

In the 1870s, the UP used its cars for shipping meat to packinghouses in Omaha and Chicago. A system of stockyards and slaughterhouses developed which enabled cattle grown on the Wyoming ranges to be shipped to Chicago for slaughter with the beef then transported in refrigerated cars to the East Coast and even to Europe. This helped create Wyoming’s cattle industry, which brought huge investment into the territory from the East and from Great Britain, and led to the construction of the lavish Cheyenne Club where cattlemen enjoyed fine dining and urban luxuries on the Wyoming high plains.

In 1884, the UP began selling some of its land grant acreages to prominent Wyoming livestock growers like F.E. Warren, the Wyoming Central Land and Improvement Company, the Swan Land and Cattle Company and George Baxter.

In 1886, Congress passed a law allowing the taxation of all railroad-grant land, regardless of whether final patents had been issued.

The builders build the road

Nearly every one of the construction managers and engineers who built the road had served as Union officers in the Civil War, and they brought their organizational and logistical prowess to bear in commanding the work. The chief railroad engineer, Grenville Dodge, had rebuilt lines in the South during the war while serving as a Union general.

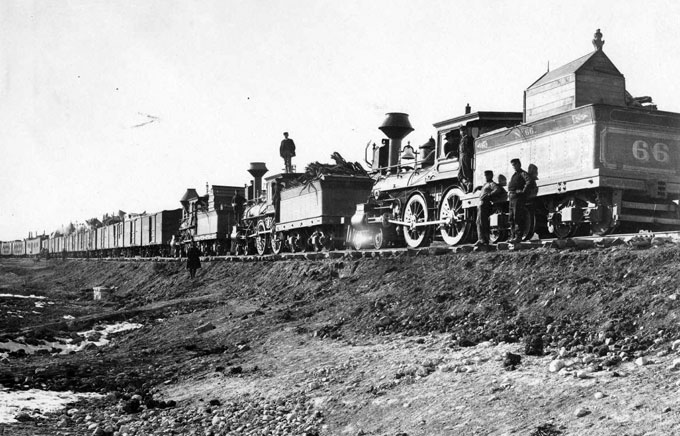

On Dec. 2, 1863, construction began on the railroad in Omaha, Nebraska Territory, but only made 40 miles by the end of 1865. The following year the line made it 260 miles, stopping at North Platte, Nebraska Territory for the winter. In 1867 the road made it another 240 miles before stopping at Granite Canyon on the slopes of the Laramie Range west of Cheyenne. The following year construction raced across 500 miles of southern Wyoming, entering Utah at the beginning of 1869.

Surveying was considered as some of the most hazardous work for the Union Pacific Railroad, particularly in 1867, when two chiefs of survey crews, Lathrop L. Hills and Percy Browne, died during attacks from Indians. Browne’s party suffered three separate attacks before he perished. James Evans replaced Hills, and became the namesake of Evanston, Wyoming Territory. Dodge also honored surveyor John A. Rawlins by naming a town for him.

The surveyors also took on the tough duty of camping out for the winter of 1866-1867 at the summit of the Laramie Range to make sure they located the line away from deep snowdrifts.

The surveyors eventually linked a series of topographic features to create a favorable route. From the East, a natural pass or “gangplank” up the Lodgepole Creek Ridge west of Cheyenne provided a steady grade over the Laramie Range, followed by an easy descent onto the plains of the Laramie Basin.

From there the route rounded the northern slope of Elk Mountain to reach the North Platte, moving on to enter the Wyoming Basin, also known as Great Divide Basin over a low ridge north of Bridger Pass. After leaving that basin, the railroad picked up Bitter Creek as a watered route into the Green River Basin. From there the route followed the right bank of the Green River to Black’s Fork, then crossed over a ridge into the Bear River drainage, and then another ridge into Weber Canyon and the Great Salt Lake Basin.

Track-laying crews completed the line into Cheyenne on Nov. 13, 1867. Dodge laid out the town site and selected the location for locomotive shops. The following March, the Union Pacific board of directors selected the town as the location for a major depot and repair shops, ensuring Cheyenne’s future as an important railroad town.

Cheyenne grows; more end-of-the-tracks towns appear

Within a few months of its founding, Cheyenne had a population of 4,000 people, earning it the nickname of “The Magic City of the Plains.” The end of the tracks stayed in Cheyenne for nearly six months due to difficult construction over the Laramie Range, which gave the town more of an economic boost than other end-of-the-tracks towns that had much shorter heydays.

Like all such towns, Cheyenne businesses provided materials for the railroad as well as entertainment for the workers. Cheyenne boasted nearly 70 places to buy a drink in 1868, along with numerous brothels, gambling houses and theaters. Among the city’s gainfully employed were actors, dancing girls, fiddlers, banjo players and bagpipers.

Cheyenne also hosted the “Big Tent”, a notorious canvas wall tent set up in different towns as the end of the tracks moved across Nebraska and Wyoming. Inside, customers who spent enough money could get a drink, play a game of cards, dance with a girl, hire a prostitute and get treated for venereal disease all in one visit. Such mobile tents, along with the lawlessness they attracted, gave the end-of-the-tracks towns a descriptive nickname: “Hell on Wheels.”

By February 1868, as the end of the tracks moved west, Cheyenne started to lose population to Laramie, underscoring the city’s dependence on the UP and the transient nature of the railroad boom.

By May 4, 1868, crews had laid rails all the way to Laramie, but not before building across the formidable Sherman Summit, also known as Sherman Hill. At an elevation of 8,200 feet, the rail line over the Laramie Range became the highest railroad in the world at the time. Just west of the summit, a gorge created by the miniscule Dale Creek required the largest bridge built by the Union Pacific west of the Missouri River. The timber for the Dale Creek trestle came from the forests of the upper Midwest. In total, the bridge measured 125 feet high and 1,400 feet long.

Laramie’s first few months brought a degree of lawlessness not seen in Cheyenne. Robberies occurred daily. Vigilantes responded by killing the perpetrators without trials. The first elected mayor wrote a letter of resignation explaining that incompetent city officers made it impossible for him to administer the town's provisional government.

Railroad money attracted a large, varied assortment of people. Some stayed; many moved on to other opportunities. For every town father like Laramie banker Edward Ivinson, there were dozens of free-floating laborers, unattached men, prostitutes, gamblers, swindlers and thieves who scavenged the dollars spilling out of the pockets of the rail workers.

Luckily, the end of tracks moved on as crews moved north across the Laramie Plains. Benton, Wyoming Territory, near the crossing of the North Platte River, became an even more notorious Hell on Wheels town because of its incredible consumption of whiskey. But this town did not survive.

Perhaps the worst incidence of violence in a “Hell on Wheels” town occurred in Bear River City southwest of Evanston on Nov. 3, 1868, when vigilantes broke into the jail to capture and lynch three “garrotters.” A riot ensued, and the local police took refuge in a store as a mob burned the jail and the office of the Frontier Index. The editor of the newspaper, Leigh Freeman, fled the town for Fort Bridger. The police shot their way out of town. Twenty-five of the rioters died in the foray and another 50 or 60 were wounded.

Aside from Sherman Summit, Wyoming’s major physical obstacle was crossing the high divide between Black’s Fork of Green River and the Bear River Drainage. The route required steep grades of 90 feet per mile. On Dec. 16, 1868, the railroad arrived in Evanston on the Bear River.

The Trains Create Faster Cross-Country Passage

The rails moved into Utah around the beginning of 1869. With that, the river of construction money with tributaries in the East and Europe began to dry up.

The cash had provided the explosive energy that dynamited the road cuts and fed the sweating mules that graded the right of way. It motivated the 10,000 men who cut down timber for railroad ties and spiked countless rails across the high plains of Wyoming. But when the railroad shifted into maintenance and operation mode, many of those workers moved on to new opportunities.

In the summer of 1869, the non-Indian population for all of Wyoming Territory stood at 8,104, with 2,305 in Cheyenne; 2,027 in Albany County; 460 in Rawlins; 1,923 in Sweetwater County. Acquiring enough population to gain statehood would take another 20 years.

Wyoming Territory had a railroad, but rather than bringing settlers to the area, it served mainly as a transportation route between the eastern states, the Pacific Coast and Asia, and as a military transport system. The railroad played a major role in killing off the buffalo and efficiently delivering troops that broke the resistance of the American Indian tribes of the norhtern plains in the late 1870s.

Before the railroad was completed, the trip from Missouri to remote places like northern Wyoming Territory took months. The railroad reduced that travel time to a matter of weeks, putting the military in position for the final push to force the Lakota and Cheyenne onto reservations, which finally happened after the Black Hills gold rush and the 1876 Powder River campaign made famous by Gen. George Custer’s defeat at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

The Union Pacific brought in the first sizable influx of permanent non-Indian residents to Wyoming. Out of the lawless chaos of railroad construction camps emerged towns that gradually grew more orderly. The railroad also created supporting industries, including locomotive maintenance, steel manufacturing, coal mining and logging for railroad ties.

Given the fickle nature of railroad management, business owners found it hard to tell which towns would grow, and more cautious merchants stayed in Cheyenne and Laramie. Until other railroads built into Wyoming beginning in the 1880s, almost all the population of the territory lived in the UP railroad towns of Cheyenne, Laramie, Rawlins, Rock Springs, Green River and Evanston.

Many towns that the railroad didn’t favor withered and died, however. Squatters often occupied lots in the towns without buying the land from the railroad. The railroad called on the U.S. Army to drive out squatters in Cheyenne, Green River and Brownsville near the North Platte.

Shaky finances make for low-quality construction

The railroad served its purpose of providing transportation, but it was neither well built nor safe. Workers died in boiler explosions, falls from moving trains and collisions. Some brakemen broke their necks on snow sheds with low clearance. The hastily built Union Pacific line needed to be rebuilt almost from the moment of its completion. Grenville Dodge later referred to the railroad he built as “two ballasted streaks of rust.”

The quality of construction suffered because of financial shenanigans on the part of company board members. Thomas Durant, along with Oliver and Oakes Ames, had formed a construction company called Crédit Mobilier, through which the Union Pacific funneled the payments for its contractors. Crédit Mobilier took in much more money from the UP than it paid out in expenses. The promoters of the company earned between $13 million and $16.5 million in profit after an investment of $4 million.

Some of that profit went to dozens of members of Congress to whom Oakes Ames sold shares of Crédit Mobilier stock at deeply discounted prices. Congress censured Oakes Ames after investigating the scandal, and destroyed both brothers' reputations in the process. Oakes Ames died in Massachusetts soon afterward, in 1873. The UP later built the Ames Monument on Sherman Summit between Cheyenne and Laramie in an effort to restore the tarnished memory of the brothers. The monument was finished in 1882; in 1883, the Massachusetts Legislature passed a resolution exonerating Oakes Ames.

In the late 1870s, meanwhile, the UP began replacing the soft iron of its original rails because the metal wasn’t strong enough to bear the traffic. The company established a rolling mill in Laramie, where it transported the original scrap iron rails to be re-rolled into steel.

To attract the rolling mill, Albany County agreed to provide $18,000 to the UP, to levy no taxes on the mill for 10 years, and to reduce taxes for other UP property. This cut the county’s assessed valuation by nearly $91,000. The UP completed the rolling mill at a cost of $188,293 and employed about 100 men. The mill stood as Wyoming’s leading manufacturer for many years until it was destroyed by fire in 1910 and not replaced.

The Union Pacific did not take on further construction in Wyoming Territory until 1884, when it seized on an opportunity to gain its own connection to the Pacific Coast. By building northwest from Granger, Wyo., toward the Columbia River, the railroad company gained a connection with the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company and a route to Portland. This freed the UP from its previous reliance on the Central Pacific to haul its traffic west from Utah.

Violence and robberies plague the line

The Rock Springs Massacre occurred in 1885, when a gang of disgruntled white miners attacked the Chinese neighborhood in Rock Springs, burning houses and killing 28 Chinese miners in one of Wyoming’s worst incidences of ethnic violence. Territorial Gov. F.E. Warren called in the military to quiet the disturbance, and the Chinese gained rail passage to Evanston only to be sent back to Rock Springs by railroad management.

In 1899 and 1900, Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch stopped UP trains in Wyoming to rob passengers and break open the safes in the express cars. The first robbery occurred on June 2, 1899, at Wilcox, just north of Rock River, after which a large posse pursued the thieves to no avail. Union Pacific Board Chairman Edward Harriman attempted to contact Cassidy regarding these robberies, but the meeting never took place. On August 29 of the following year the outlaws pulled off another robbery near Tipton, Wyo. These were some of Cassidy’s most famous exploits.

While such thievery made for sensational headlines, a much greater disaster occurred in 1903, when a Union Pacific coal mine exploded in Hanna, killing 169 miners. In 1908, another explosion in Hanna killed 59 men. The remains of the dead still lie in the mines, because there was no way to retrieve them.

Bankruptcy leads to reorganization

In 1893, the country descended into a financial panic. Transcontinental traffic plummeted and did not generate enough income to pay the interest on the UP’s debts. This caused the company to fall into receivership. A court-appointed receiver took control of all the assets and income in order to ensure payment to creditors.

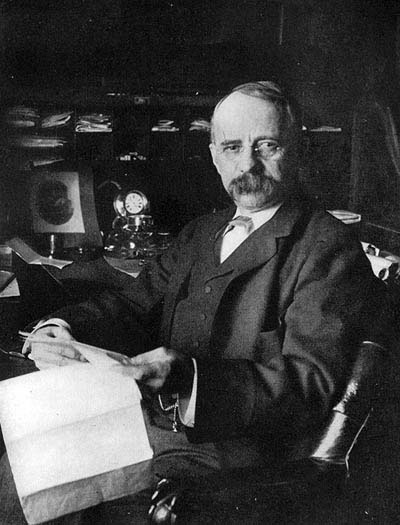

The receiver reorganized the company and improved bridges, rolling stock and rails. The revamped company was auctioned in Omaha in November 1897. A group of investors bought the company for $81.5 million, and Edward Harriman won election as chairman of the board.

Harriman traveled the whole route in an observation car to see for himself where problems might be fixed and more money made. Then in 1898, the UP embarked on an extensive reconstruction project to make the railroad operations more efficient. The first phase of the project cost $25 million, and in the end, under Harriman’s leadership, the UP spent $98 million on improvements and $62 million to build or buy new lines: $160 million total.

The line in Wyoming saw some of the most significant improvements. On Sherman Summit in the Laramie Range, workers relocated the tracks several miles south and away from the town of Sherman, the Ames Monument, and the rickety Dale Creek Trestle. Harriman ordered that the line be double-tracked in this area, while preserving the old line. An 1,800-foot tunnel combined with a 900-foot dirt fill over Dale Creek made for a net reduction of 250 feet in the line’s elevation.

These improvements straightened the line and reduced the overall grade on that section from over 68 feet per mile to 43 feet per mile.

Engineers also reduced curvature near Green River by cutting new roadbeds into nearby shale ledges—difficult work. But the biggest change in Wyoming shortened the crossing over the Bear River Divide from 21 miles to 10 miles when a 5,900-foot tunnel was dug through Aspen Mountain. Tunnel construction began in 1899. Crews faced difficulties with flooding and oil seepage as they dug through soft coal deposits. At one point a gas explosion killed several men and mules. The tunnel finally opened in 1901 after 30 months of work.

Harriman also called for improvements to railroad depots, like adding electric lights and heat. In the alkali-soil town of Rock Springs, he had hundreds of carloads full of good soil delivered so the trees and shrubs they planted could survive. In Cheyenne, Rawlins, and Green River he saw that workers improved parks.

Harriman finished most of his improvements by 1902, but even after his death in 1909 work continued on double-tracking the UP line across Wyoming all the way to Granger, Wyo. until 1917. Edward Harriman’s son Averell later served as president of the UP from 1932-1946.

While a small portion of the improvements were cosmetic, the overall effect of Harriman’s efforts made the UP into the most profitable railroad among its peers, earning $8,167 in revenue per mile compared to the $7,528 earned by its closest competitor.

World War II brings technological developments

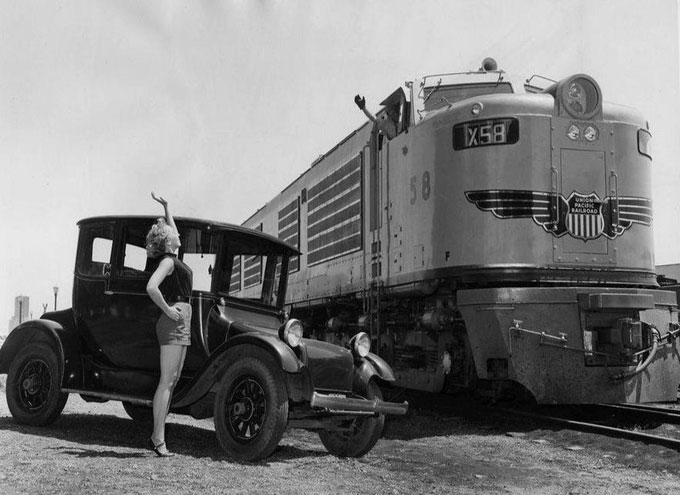

At the beginning of World War II, the UP developed the 4000-class Big Boy steam locomotives, the biggest and most powerful engines that represented the climax of steam technology. At top speed they could reach 80 miles per hour.

The power of the Big Boy engines surpassed the already advanced 9000-class steam locomotive, which had the capacity to pull trains at a swift 50 miles per hour. The 9000-class boasted a very long wheelbase and served the route from Iowa to Green River, Wyo. In 1948, UP began using gas turbine electric locomotives on some trains.

Advances in rolling stock kept pace with the constant improvements in infrastructure. In 1952 and 1953, an $18 million project reconstructed the line over Sherman Hill, and a new line created an easier passage over the divide west of Rawlins between the North Platte and the Great Divide Basin.

The UP’s Big Boy locomotives remained in use until 1959. Large crews based in the Cheyenne shops maintained these machines in top condition for the demanding climb over Sherman Summit to Laramie.

On July 23, 1959, the last steam train made a run from North Platte, Neb., to Cheyenne, ending the era of steam power and causing a major transition in the working lives of the skilled laborers in Cheyenne’s steam locomotive shops.

The late 20th century brings expansion, improvements

The latter 20th century brought advances in technology, corporate organization and the UP’s first expansion in to northern Wyoming. The UP’s computer control system for trains debuted in 1969. The same year, the Union Pacific Corp. formed as an umbrella company over the Union Pacific and its various subsidiaries. Increased travel by interstate highways and air transportation reduced the UP’s passenger business to the point that Amtrak took over that traffic in 1971.

On Aug. 16, 1984, the UP opened a connector line to the coal fields of Campbell County, Wyo., allowing it to compete with the Burlington Northern in that region. End-of-train units eliminated the use of cabooses in 1984. Double-stack trains that carried two storage containers on one car debuted soon thereafter.

The legacy of the UP in Wyoming

In politics, economy and culture, Wyoming began as a colony of the Union Pacific Railroad, and it still bears signs of those origins today.

By the end of the 20thcentury, the UP continued as a strong economic force in Wyoming, though other kinds of development diminished the influence it had in the territorial era. It took until the 1970s—a full century after the golden spike—for the mineral industry to unseat the railroad as the most powerful industry in the state. Mineral severance taxes since then have far surpassed railroad property taxes as a major funding source for state government operations.

Yet patterns set by the railroad remain. The argument about how to tax UP property laid the groundwork for discussions on how much to tax corporations in Wyoming. The push-and-pull dynamic that first existed between railroad lobbyists and territorial legislators in the late 1800s continues today between advocates for fossil fuel industries and Wyoming lawmakers.

The influence of the UP in Wyoming government endured after the turn of the 20thcentury. A 1908 editorial in the Cheyenne Leader, a Democratic newspaper, remarked that, "The Union Pacific has ruled Wyoming ever since it was organized as a territory. It controlled and used the Republican machine and has owned every legislature with one possible exception in forty years."

Wyoming’s political culture carried the mark of the UP’s presence for generations after initial construction. The southern tier of counties along the UP line developed first, and as a result became the location of the state’s most important institutions: the university in Laramie, the state prison in Rawlins, the state hospital in Evanston and of course, the Wyoming Capitol in Cheyenne.

Wyoming’s central and northern counties developed later and with smaller initial populations, meaning that political representation and power centered along the older towns along the UP line. This bred resentment of the southern counties and towns, and of Cheyenne in particular, as northern politicians tried to gain state support for their counties.

To this day, Wyoming’s political party demographics are influenced by the fact that the UP’s 19th and 20th century coal mines in Carbon, Sweetwater and Uinta Counties, and its machine shops in Cheyenne attracted union representation, making those communities a stronghold for the labor movement and the Democratic Party, even as the UP leadership courted Republican leaders in the statehouse.

Wyoming brands itself with the images of women’s equality and romantic cowboys. But in reality, the industrial force of the railroad defined Wyoming from the beginning of the territory.

Resources

Primary Sources

- The Frontier Index,1868. This newspaper was published in the succession of end-of-tracks towns as the Union Pacific was built. Access it by searching the Wyoming Newspaper Project.

Secondary Sources

- Coutant, C.G. The History of Wyoming from the Earliest Known Discoveries. Laramie, Wyo.: Chaplin, Spafford, and Mathison, Printers, 1899, 621.

- Farnham, Wallace D. "Grenville Dodge and the Union Pacific: A Study of Historical Legends," Journal of American History, LI, no. 4 (March 1965): 638-639.

- King, Robert A. Trails to Rails: A History of Wyoming’s Railroads. Casper, Wyo.: Endeavor Books—Mountain States Lithographing, 2003, 11-42.

- Klein, Maury. Union Pacific: Birth of a Railroad 1862-1893. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1987, 1-212, 480-497, 641-658.

- __________. Union Pacific: Volume II 1894-1969. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006, 28-30, 49-68.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 36-41, 52-58, 62-63, 77,108-111, 117, 148, 175, 200, 222-223, 295, 339, 341-342, 378, 489, 523.

- McPhee, John, Rising from the Plains. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1986, 54-64.

- Union Pacific. “150 Years: The History of Union Pacific.” Accessed Dec. 29, 2012, at http://www.up150.com/timeline.

- ___________. “Charting the Future.” A three-minute video on Harriman and the UP reconstruction. Accessed Feb. 2, 2013, at http://www.up150.com/player/1344491048001.

- Vance, James. The North American Railroad: Its Origin, Evolution, and Geography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995. 148-181, 204-206.

- ___________. “The Oregon Trail and the Pacific Railroad, a Contrast in Purpose.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 51, no. 4 (December 1961): 368. Accessed Feb. 2, 2013 at http://cascourses.uoregon.edu/geog471/pdfs/1206/vance_railroads.pdf.

- White, Richard. It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own: A New History of the American West. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993, 246-257.

For Further Reading

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Nothing Like it in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-69. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000. This book provides a readable narrative of the construction of the railroad, but contains factual errors.

- “Progress of the Union Pacific.” Golden Spike National Historic Site. National Park Service. Accessed March 6, 2018 at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/hh/40/hh30l.htm.

- United States Citizenship. "Chinese Immigration and the Transcontinental Railroad." Accessed May 6, 2014 at http://www.uscitizenship.info/Chinese-immigration-and-the-Transcontinental-railroad/. Good article on the topic, with links to much more information about Chinese immigrants, their role in building the transcontinental railroad and more.

- White, Richard. Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2011

Illustrations

- Accompanying the article, all the images except the “Great Event” poster are from Wikipedia, and used with thanks.

- In the photo gallery, the early photos of Granite Canyon and the Sherman roundhouse are from the USGS photo library, used with thanks. Andrew J. Russell’s photo, Temporary and Permanent Bridge Green River Citadel Rock in Distance, c. 1868 is an Imperial plate collodion glass negative, 10 x 13, is from the Andrew J. Russell Collection, the Oakland Museum of California. Used with permission and thanks. The scan of the 1885 William Henry Jackson photo of the train crossing the Dale Creek trestle is from the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Used with thanks.