- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Edward Gillette: Surveyor, Statesman, Entrepreneur

Edward Gillette: Surveyor, Statesman, Entrepreneur

Prior to 1878, Edward Gillette had never been west of New York. He was Connecticut born and bred and had graduated from Yale University in his hometown of New Haven. On paper he looked like a New England tenderfoot, but Gillette would prove to be anything but. In July 1878, at the age of 23, he was appointed assistant topographer on the United States Surveys being conducted by the engineering department of the Army in New Mexico. Once he received his orders, he had eight days to report to Santa Fe.

Image

Traveling to Santa Fe

The trip out was one Gillette would never forget. The first leg was by train. At one town in Missouri a rowdy gang, calling themselves a political organization, boarded the train and proceeded to drink, shout and shoot their guns through train car’s roof. They took a shine to Gillette. In his autobiography, Locating the Iron Trail, he remembered that, “[t]wo delegates crowded into the seat with me and said we would have a ‘hell of a time’ on arriving in Kansas City... I was adopted in the freest and heartiest manner possible as a member of the gang and the two fellows in the seat with me constituted a guard to see that I did not escape.” After the gang departed the train, things seemed to calm down.

But that was not the only bump in the road on his trip. He faced a two-day stagecoach ride to Santa Fe after arriving in El Moro, Colo., near Trinidad, where the railroad ended. His driver did not instill confidence in his lone passenger when he arrived drunk on July 28, 1878, after an all-night Mexican dance. The driver drank three more whiskeys before he felt ready to drive. Gillette bounced painfully inside the stagecoach. With effort Gillette convinced the driver to stop and gladly climbed up to next to him. The driver admitted to Gillette that he had shot a couple of people at the dance the night before and thought it best to get out of the area for a while.

Adding to the surreal experience, July 28 was the day of the Great Eclipse of 1878. While tourists flocked to places like Colorado to watch, Gillette witnessed the event from the front seat of a stagecoach at the mercy of a drunk driver. The driver’s reckless driving and breakneck speeds eventually snapped one of the wheels off the stagecoach. Gillette jumped into a clump of cactus to save himself from the crash. The driver wasn’t so fortunate. Gillette pulled him from the wreckage, fixed the stagecoach, loaded up the injured driver, and drove to the next stop.

Surveying in the West

Despite this harrowing introduction, Gillette would spend the rest of his life living and working in the American West. He worked on projects for the government and for various railroad companies in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Nebraska, and South Dakota in positions of increasing responsibility. By 1881 he’d become the head draftsman for the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad and was based out of Utah Territory. In 1884 he began working for the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad in charge of a locating party. His team’s responsibility was to locate the most economical route for the railroad by investigating grade, distance, and other factors to inform their recommendation. His work began in Nebraska, worked up through the Black Hills of present-day South Dakota, and into Wyoming Territory.

In the late 1880s Gillette’s team was surveying a route between Donkey Creek and Hay Creek in eastern Wyoming Territory. The team found a route that saved the company significant money because it was five miles shorter, needed less grading, and needed 30 fewer bridges. The men were excited to potentially get a bonus for their good work. Instead, the chief engineer wrote to the crew that Donkey Town—the tent town on Donkey Creek-- would be renamed Gillette as a reward. Thus Gillette, Wyo. got its name from a man who never lived there.

Gillette’s team moved west ahead of the construction of the rails and surveyed the route into the Sheridan area in fall 1890. There was much debate among people about which of the communities in the area would get the railroad and all the benefits it would bring. Would it be Sheridan? Big Horn? No one knew for sure. The recommendation was in the hands of Edward Gillette and his team. They chose Sheridan as the next stop for the railroad. The people of Sheridan were grateful because they benefitted from the money spent by the railroad company during construction.

The influx of cash allowed many Sheridan business owners, and nearby ranchers, including Gillette’s future father-in-law, Henry Coffeen, to pay off debt and expand their businesses. Sheridan’s economy continued to improve while it was the terminus for the railroad and long after. The appeal of the thriving community was so strong that Gillette and three other men on his locating team eventually ended up living permanently in Sheridan.

Image

Image

Exploring Bighorn Canyon

Gillette’s next adventure made history. In 1891, the rail line needed to cross the Crow Reservation. While they waited for a permit to survey the reservation, the team moved to the Wyoming-Montana border where it crosses Bighorn Canyon. Bighorn Canyon is a 55-mile-long, steep-walled, box canyon with swift moving water. The walls in some places reach 2,500 feet high.

Crossing the reservation, Gillette tried to get as much information as he could about the canyon. No one had ever survived a trip through it. The challenge called to Gillette’s sense of adventure, so he decided to try.

On March 7, 1891, Gillette and N.S. Sharpe, a gold prospector Gillette had previously met in the Black Hills, set out. The temperature was a miserable negative twenty degrees. For most of the journey they walked on the frozen river itself because the walls of the canyon are so steep that there wasn’t a shore to speak of. The trip was only possible because of the cold—and the ice.

Moving as fast as they could, Gillette and Sharpe recorded wall heights and some preliminary survey information. The men faced deep snow, rapids and cliffs. At times they had to wade through water that was sloshing over the ice. Near the end of the canyon the ice became dangerously thin, so they had to get creative. In his autobiography Gillette wrote:

“…it was concluded to experiment with Sharpe, as he was considerably lighter than myself. A rope was firmly tied around him and he squirmed over the undulating ice while I let out the rope, ready to pull him back should he break through the ice. He made the shore outside the cañon all right, and, after sending over the outfit, I lay down on the ice and gradually worked my way out of the cañon. It was a great relief to walk along the bank of the river and contemplate the fact that we had gotten safely through the entire cañon, as the water was rising rapidly in the river. Had we been a few days later the trip we made would have been impossible.”

Image

Prospering in Sheridan

Gillette married Harriet “Hallie” Coffeen, daughter of Congressman Henry and Mrs. Harriet Coffeen, on April 10, 1893. They settled in Sheridan and had three children. Gillette continued working for the railroad and expanded his holdings in Sheridan by purchasing land and interests in local businesses.

Image

In May 1893, ads began appearing in the Sheridan newspapers for Edward Gillette & Co., Real Estate Dealers and Surveyors that ran for multiple years. The company advertised that they had 500 lots with easy terms and special incentives to build. Gillette went into this venture with M.G. Swan, who had been part of his original locating team, and J.D. Helvey.

Gillette served on the board of multiple Sheridan businesses including Sheridan Electric Co. and the State Bank of Sheridan. Beyond his business interests, he was active in the community with the Republican Party, Sons of the American Revolution, and more. He hardly stayed confined to the Sheridan city limits, exploring the Bighorn Mountains and making discoveries there like Dome Lake in 1893.

He rose to the position of superintendent of Burlington Routes West before leaving the railroad in 1906. His career also included public service, being elected Wyoming state treasurer from 1907-1911 and, in the late 1890s, an appointment as superintendent of Division II of the State Board of Control. (Wyoming is divided into four districts for administration of its water laws; District II includes land drained by the Powder, Tongue, Belle Fourche and Cheyenne rivers—the northeast quarter or so of the state. Superintendents work with users to handle local water-right issues and as a board—with the state engineer, the chief water officer—they act to establish, change or eliminate water rights.)

Throughout his life Gillette always advocated for the advancement of Sheridan, saying it could be bigger and better than cities like Billings and Cheyenne. A true engineer, he always pushed for development and growth. He died on Jan. 3, 1936 after a long illness, but still lives on in the history of Sheridan and the American West.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support which in part made this article possible.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- Gillette, Edward. Locating the Iron Trail. Boston: Christopher Publishing House, 1925. Reprint. Wyoming: Wyoming State Historical Society, 2015, 12-14, 28, 31, 43, 53-54, 57-65, 115.

Newspapers

- Cheyenne Daily Leader, April 19, 1893, p. 3. Accessed March 30, 2023 at https://wyomingnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WYCDL18930419-01&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

- The Enterprise, June 25, 1892, p. 4. Accessed Mar. 30, 2023 at https://wyomingnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WYSRE18920625-01&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

- Sheridan Daily Enterprise, Nov. 10, 1909, p. 1. Accessed March 30, 2023 at https://wyomingnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WYSRD19091110-01&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

- The Sheridan Post, Jan. 28, 1892, p. 4. Accessed March 30, 2023 at https://wyomingnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WYSRP18920128-01.1.4&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

- The Sheridan Post, Feb. 15, 1894, p. 5. Accessed March 30, 2023 at https://wyomingnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WYSRP18940215-01.1.5&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

- The Sheridan Post, May 3, 1894, p. 5. Accessed Mar. 30, 2023 at https://wyomingnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WYSRP18940503-01.1.5&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

- The Sheridan Post, Jan. 2, 1902, p. 1. Accessed Mar. 30, 2023 at https://wyomingnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WYSRP19020102-01&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

Secondary Sources

- Colorado Encyclopedia. “Great Eclipse of 1878.” Accessed March 1, 2023 at https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/great-eclipse-1878.

- Karpan, Kathy, Margy White and Dawn Hill. 1991 Wyoming Official Directory. [Cheyenne: 1991.]

- Mackey, Mike. Henry A. Coffeen: A Life in Wyoming Politics. Sheridan, Wyoming: Western History Publications, 2012, 14-15.

- MacKinnon, Anne. Public Waters: Lessons from Wyoming for the American West. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2021, 16-17, 44-45.

- Ringley, Tom. “Sharing Sheridan's history through Edward E. Gillette.” The Sheridan Press, Dec. 23, 2021, accessed March 1, 2023 at https://www.thesheridanpress.com/opinion/columnists/sharing-sheridans-history-through-edward-e-gillette/article_4b1326d2-5146-11ec-aa88-a7f80d5fa762.html

For further reading and research

- Ringley, Tom. “Sharing Sheridan’s History through Edward E. Gillette.” Sheridan Press, Dec. 23, 2021, accessed April 2, 2023 at https://www.thesheridanpress.com/opinion/columnists/sharing-sheridans-history-through-edward-e-gillette/article_4b1326d2-5146-11ec-aa88-a7f80d5fa762.html.

Illustrations

- The portrait of Edward Gillette and the photo of him in the wagon—the picture is undated and the other people in the wagon are unidentified—are from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The 1908 photo of downtown Gillette is from the Campbell County Rockpile Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

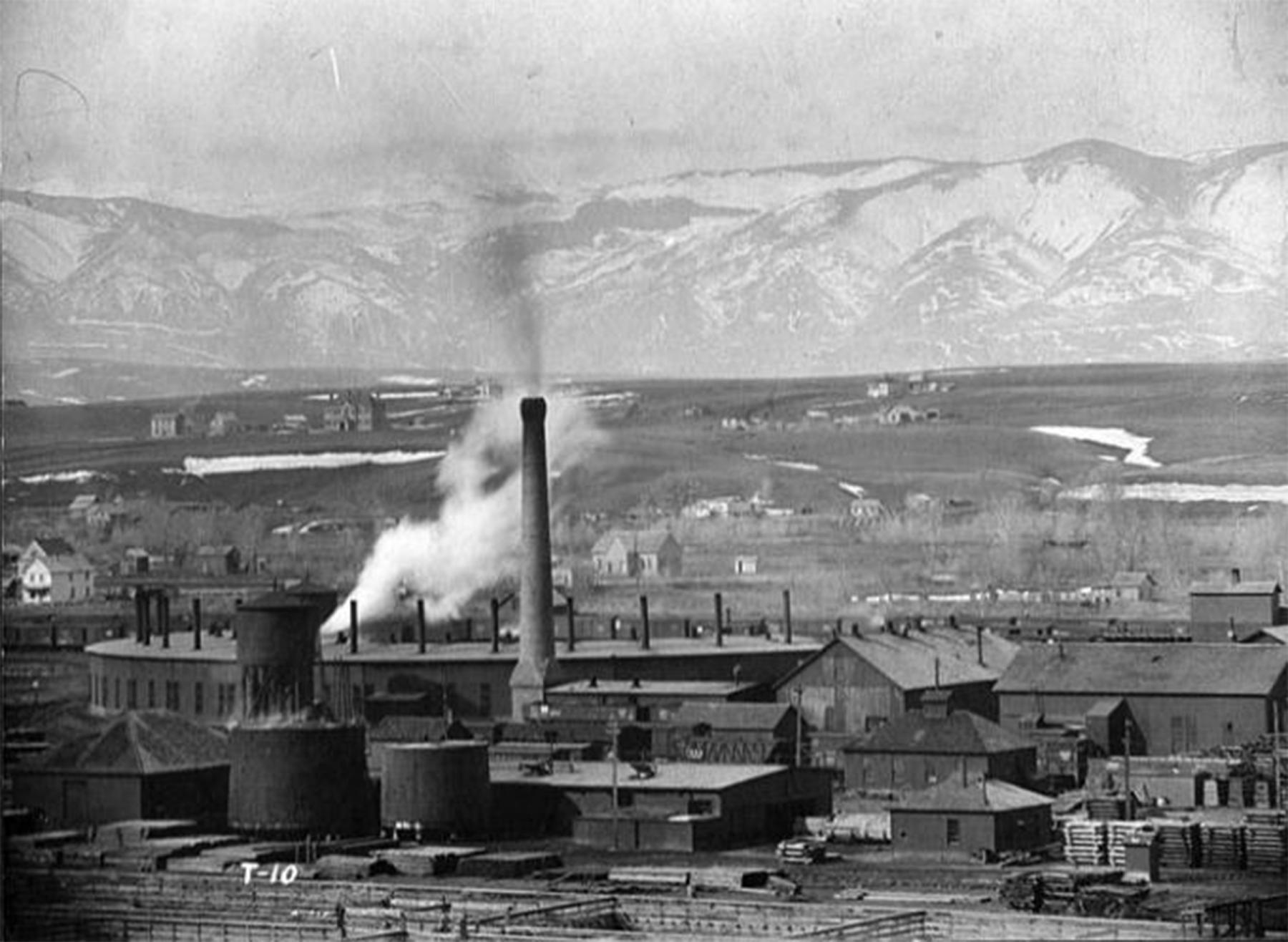

- The 1910 photo of the Burlington roundhouse and railyards was shared with us years ago by the Sheridan County Museum, now called the Museum at the Bighorns. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of a snow-dusted Bighorn Canyon is from the National Park Service, via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.