- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Lincoln Highway In Wyoming

The Lincoln Highway in Wyoming

In 1913, the nation’s first transcontinental highway followed Wyoming’s southern rail corridor. A well-publicized effort led by eastern automakers, the Lincoln Highway introduced tourists, especially women, to the wonders of Wyoming. It also spurred businesses in the state. Although its official life lasted little more than a decade, the route lived on as U.S. Route 30. Since the construction of Interstate 80, the Lincoln Highway has become a touchstone of nostalgia for a friendlier, more easygoing type of auto touring.

An idea and a marketing campaign

"The highways of America are built chiefly of politics, whereas the proper material is crushed rock, or concrete," wrote Carl G. Fisher in 1912. Fisher (1874-1939), a manufacturer of automobile headlights, had just developed the Indianapolis Speedway. Now he wanted to build a “coast-to-coast rock highway” from New York to San Francisco. He argued, “The automobile won't get anywhere until it has good roads to run on.”

Fisher recruited other industrialists into an association to promote the idea. They decided to name the road after Abraham Lincoln, one of Fisher’s heroes. Lincoln had been dead less than 50 years, and needed remembering. The marble memorial in Washington, D.C. did not yet exist, and a nationwide highway might be closer to the people.

Henry Bourne Joy (1864-1936), president of the Packard Motor Company, agreed to serve as president of the Lincoln Highway Association. Joy insisted that the highway take the shortest, most direct route across the country. It would not detour to national parks, nor to cities such as Denver that lobbied for it.

The association raised $2 million in its first year. But Henry Ford refused to contribute, saying that governments, not automakers, needed to pay for roads. At the time, roads were built by county governments, which had no incentive or method to coordinate linked interstate routes. Many state constitutions prohibited the state from paying for roads. The federal government, much smaller in those days, was reluctant to take on a new role. After all, railroads had been privately built, although heavily subsidized.

Meanwhile, driving cross-country required so much time and money that it was a rich person’s pastime, akin to having a private plane today. Why should it receive huge subsidies from taxes paid by all? Yet many local businesses wanted the benefits of increased tourism that would come with cross-country travel.

Leaders of the Lincoln Highway Association soon realized that Ford had a point. It could not afford to build highways. Instead, it would relabel existing roads. In today’s terms, it did software, not hardware: Its signs, guidebooks, and marketing would improve the user experience of driving cross-country. But the physical infrastructure would be provided by others. This was a particular challenge in Wyoming. Compared to other states, it had fewer existing roads and smaller populations to pay for new ones.

The association ended up spending most of its money on publicity. By painting the Lincoln Highway as a nationwide patriotic movement, it could persuade local, state, and federal governments to pay for road construction. It spurred the “Good Roads movement”—the tax-and-spend, big-government corporate-welfare idea of its time.

Choosing a path

Wyoming’s relatively easy routes through the Rockies have made it a leading setting for many forms of trans-mountain transportation: the Oregon, Mormon, Pioneer, and California Trails, Overland Trail, Bozeman Trail, Union Pacific Railroad and the Burlington route. The first transcontinental auto road, prioritizing a short, direct route, would similarly choose Wyoming.

In the initial construction of the Union Pacific railroad from 1867-1869, the government was paying by the mile. So surveyors tended to plot leisurely routes that followed the terrain on low grades. Beginning in 1898, the Union Pacific spent $160 million on upgrades, often to shorter routes with steeper grades that could be handled by new, more powerful locomotives. It then abandoned the old route. For the Lincoln Highway, that abandoned right-of-way was usually the best, and sometimes the only, east-west path available.

Thus the creation of the Lincoln Highway wasn’t really about building roads—it was more about marking them on a map. Some of the roads were major city streets or county-built market roads. Many were abandoned railroad rights-of-way. And some were mostly theoretical paths across the prairie. But not entirely so: people had already driven this route across the country. The first was Alice Huyler Ramsey in 1909; she did it in a Maxwell, at age 21, accompanied by a year-old baby.

Public right-of-way was an important factor in choosing the route. For example, west of Laramie, the highway used the old Union Pacific right-of-way in a route through Rock River and Medicine Bow, roughly today’s U.S. 30. Residents of Elk Mountain lobbied for a more southerly route, today’s I-80. But in addition to the weather concerns associated with it, the Elk Mountain route would have forced drivers to open and close 32 private-land gates.

Staying so close to the rail line meant that the Lincoln Highway had about 100 crossings of train tracks through the state. Of course there was no money for bridges. These at-grade crossings proved especially dangerous. The tracks were often higher than the surrounding landscape, so the road would crest at the crossing. But a Model T Ford, with gravity-fed gas lines, could stall out atop that crest.

Despite such drawbacks, the Lincoln Highway Association was quickly able to establish its route across the state. The association was created on July 1, 1913—and the highway was formally dedicated on Oct. 31 of that same year. Organizers encouraged every town along the nationwide route to celebrate with bonfires, fireworks and street dances. They also encouraged preachers to mention Lincoln and/or the highway in sermons the following Sunday. Many communities were happy to oblige, as the association predicted that tens of thousands of families would make the journey every year.

An ever-changing route

Today, when we look back on the Lincoln Highway, we have a romantic image of a two-lane road gliding through the landscape. We feel nostalgic for an era when driving offered a more intimate relationship with surroundings than does a massive interstate highway.

For example, Wyoming 374 west of Green River is one of those gorgeous old-fashioned drives, adjacent to the river and under Tollgate Rock and sandstone palisades. The view is so iconic that it’s on the cover of the 2013 edition of Brian Butko’s book Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: America's First Coast-to-Coast Road. And although this is indeed the Lincoln Highway, it’s only one version—the 1924 route.

The original 1913 Lincoln Highway crossed the Green River close to town on an old wagon bridge. It then ascended Telephone Canyon through drylands south of Wyoming 374. Like Laramie’s Telephone Canyon, this one was named because it provided the route of the first telephone wires. The first Lincoln Highway followed these wires, not the scenic riverside. That’s because there was only one decent bridge across the river, until the state built a new bridge, 286 feet long, for what is now Wyoming 374 a few miles upstream.

Indeed, most of Wyoming contains three or four alternative Lincoln Highways. Investments in new roads allowed for straightening, or better bridges, or flatter grades, or fewer railroad crossings, or less mud or better relations with adjacent landowners. Often the old route still exists as a two-track dirt path, though sometimes it enters private lands. But in the case of Green River’s Telephone Canyon, the only evidence of the old road is the old maps identifying it. One of the most fascinating aspects of Gregory Franzwa’s 1999 book The Lincoln Highway in Wyoming is its 118 maps—7.5-minute USGS topographic quadrangles, one inch to about 2.6 miles—charting the multiple parallel paths of the migrating highway.

To choose the right path, most travelers carried a current Complete Official Road Guide to tell them the way. The road was also marked with the red, white and blue Lincoln Highway insignia, featuring a large L. Travelers could also get the logo on pennants and radiator emblems for their vehicles.

Tourist experiences

Many people recorded their experiences on the Lincoln Highway—especially women, even including an 11 year-old girl. For example, the first full-size hardback book to discuss transcontinental travel was the 1915 Across the Continent by the Lincoln Highway by Effie Price Gladding (1865–1947). Driving west to east, she noted, “The Wyoming desert has a sharper and more vivid coloring than that of Nevada. The tableland is more rolling and the mountains are farther away.”

Gladding’s automobile was unique on the landscape. “We see white canopied wagons in the barnyards of almost every ranch house,” she wrote. The dirt ruts she drove on were often full of “chuck holes made by the indefatigable gophers or prairie dogs.”

Gladding had many pleasant experiences. For example, in Lyman, “The village street looked like a pathway of lavender.” But in Lyman she was also troubled to learn of an extralegal “‘dead line’ over which sheepmen are not allowed to take their sheep”—evidence of continuing tension between sheep herders and cattle ranchers.

Before becoming an etiquette doyenne, Emily Post (1872–1960) wrote in 1916 of a 27-day trip By Motor to the Golden Gate. “If you think Cheyenne is a Buffalo Bill Wild West town, as we did, you will be much disappointed,” she wrote. At the time, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was still alive. But progressive, up-to-date Cheyenne was lacking in the board sidewalks and yipping coyotes that Post associated with him.

Post’s friend Celia and her son/chauffeur Edwin “looked distinctly grieved at the sight of smooth laid asphalt, wide-paved sidewalks, imposing capitol and modern buildings. Even the brand-new Plains Hotel was accepted by both of them in much the same spirit as a child who thought it was going to the circus and instead found itself at a museum of art.” Having been warned about primitive conditions west of Cheyenne, Post then turned off the Lincoln Highway and headed for Denver and the Southwest.

In 1920, Grace Carmody (1909–2009) of Trenton, Neb., was a child traveling the Lincoln Highway with her family. In an early-1990s letter to Wyoming’s Randy Wagner, quoted in Franzwa’s book, Carmody explained some of those primitive conditions. West of Medicine Bow, the towns of Carbon and Hanna had no places to stay. It was getting dark, and thus dangerous to drive. They pulled into Walcott, where the only apparent lodging was a saloon with flyspecked windows. Carmody’s mother refused to stay there. Carmody wrote, “Then a railroad man directed us to a nice clean-looking house and said the people were not at home but to go in and upstairs to find a room.”

None of these chronicles mentioned encounters with Indians in Wyoming. The Lincoln Highway followed a railroad corridor that had existed for almost 50 years. One way for tribes to avoid conflict was to locate reservations far from railroad lines. For example, the Eastern Shoshone tribe chose the Wind River Reservation in part because the Wind River Range blocked these lands from the rail corridor. Although exposure to native cultures would have enriched travelers’ experiences, the absence of Native people likely contributed to a perception of safety that made women and their reading public comfortable traversing these spaces.

Growth of businesses

Increased auto travel was a boon to existing establishments such as Cheyenne’s Plains Hotel and Medicine Bow’s Virginian Hotel. But additional gasoline, auto repair, restaurant and lodging facilities emerged to serve travelers’ needs. For example, the 1921 Hotel Tomahawk in Green River was said to be one of the first Lincoln Highway-related buildings in that town. It was named after its owners, Tom Welch and J.W. Hawk.

The Black and Orange Tourist Cabins and Garage Camp were constructed in Fort Bridger in 1926. These were basic overnight accommodations, with outhouses. But each cabin featured a doorless garage for your automobile. Restored by Wyoming State Parks in 2009, the cabins are artifacts rather than lodgings, now part of Fort Bridger State Historic Park.

In 1919, future president Dwight D. Eisenhower participated in a military convoy of 73 vehicles with 258 soldiers and 39 officers on the full length of the Lincoln Highway. It was intended to test the readiness of road infrastructure for transcontinental travel by military vehicles. The convoy not only shattered bridges and culverts but experienced 50-mph winds. Years later, Eisenhower’s vivid memories of the trip drove his interest in founding the interstate highway system.

Attention paid to the convoy further increased the highway’s profile, while prompting improvements to its infrastructure. Traveler volumes increased as automobiles became more popular. Businesses thrived. And the federal government became increasingly ready to fund road construction.

The end of the road

The Lincoln Highway is generally recognized as the first east-west transcontinental automobile route. But soon it had many imitators. By the mid-1920s, the nation had more than 300 named roads. The clutter of roadside signs could be confusing.

A logical system was needed, and the federal Bureau of Public Roads proposed a numbering system. North-south roads would be odd-numbered; east-west would be even-numbered with those going coast-to-coast ending in zero. Bureau leaders made an early inquiry to the headquarters of the Lincoln Highway Association, in hopes that the granddaddy of named roads would bless the scheme.

The association had always been composed of automobile moguls. They viewed the Lincoln Highway as a method of promoting the Good Roads movement—getting governments, rather than auto manufacturers, to build roads. If the cost of getting federal money to build roads was abandoning the name “Lincoln Highway,” they could see that as a huge victory.

The road-numbering authorities initially suggested that the Lincoln Highway become U.S. 30 from the east coast to Salt Lake City, where it would merge with U.S. Route 40 to San Francisco. U.S. 40 has equally historic associations; it was built atop older trails including the National Road and the Victory Highway.

But Oregon and Idaho complained: Their only transcontinental route would then be U.S.

Route 20, impassable through Yellowstone Park in the winter. In a compromise, U.S. 30 North left the Lincoln Highway near Granger, Wyo., heading northwest into Idaho, where it then picked up the old proposed U.S. 20 to Astoria, Ore. U.S. 20 terminated at Yellowstone, while U.S. 30 South followed the Lincoln Highway to Salt Lake City, then angled north to rejoin U.S. 30 North at Burley, Idaho.

But soon U.S. 30 South was renumbered as U.S. Route 530. The Lincoln Highway lost a bit of numeric unity. Decades later, alterations made things more confusing: U.S. 530 was eliminated, U.S. 40 was terminated near Salt Lake City, and U.S. 20 was extended, crisscrossing U.S. 30 in Idaho to land on the Pacific at Newport, Ore. Only with the coming of the interstate system would a number, I-80, roughly correspond to the full Lincoln Highway.

With the 1926 implementation of the numbering scheme, however, the Lincoln Highway was finished. Within two years, the association formally disbanded. In a final act of marketing, it cast 3000 concrete posts, each seven feet long and 275 pounds. Colored concrete formed the red, white and blue logo, to which was attached a thin bronze medallion of Abraham Lincoln himself. The association arranged for a nationwide event on Sept. 1, 1928, in which Boy Scouts set the posts in holes, about one per mile.

The Lincoln Highway had lasted for 13–15 years. This was much longer than the Pony Express (1860–1861), but not as long as the Oregon Trail (1830s–1870s) or open-range cattle trails (1860s–1890s). The Lincoln Highway carried far more people than any of these, but whisked them through Wyoming more quickly. And because they tended to be vacationers rather than migrants or workers, their journey may not have felt as life-changing. Still, it was at the forefront of long-distance automobile touring, a huge chapter in the state’s development.

A highway that won’t die

Even a road without a marketing organization can still be driven on. It can still create memories. After 1928, natives and travelers alike still referred to U.S. 30 and U.S. 30 South as the Lincoln Highway. Cheyenne, Sinclair, Pine Bluffs, and other cities retained street names of Lincolnway or Lincoln Avenue or Lincoln Highway.

Thus, for almost the past 100 years—though especially after the construction of the interstate highway system in the 1960s—the “Lincoln Highway” has come to stand for a nostalgic, earlier form of automobile transportation. It’s the scenic two-lane, the free camping in a downtown park, and the sometimes kitschy roadside architecture.

Indeed, when Wyoming Public Radio did a series for the 100th birthday of the Lincoln Highway in 2013, all four of the “roadside gems” it chose post-dated the dissolution of the Lincoln Highway Association: a concrete tipi now located at Egbert (1930s), the Wyoming Motel in Cheyenne (1936), the Springs Motel in Rock Springs (1968) and Pete’s Roc and Rye saloon in Evanston (1947).

Likewise, the mostly-dinosaur-bone “Fossil Cabin” east of Medicine Bow dates to the 1930s. The Little America gas/food/lodging complex east of Granger Junction was built in 1952, replacing a 1934 version that was located on County Highway 2, south of the town of Granger. Robert Russin's 13-foot-high bronze bust of Abraham Lincoln at the summit of I-80 between Laramie and Cheyenne was dedicated in 1959. It was moved to its current location from the summit of U.S. 30/Lincoln Highway, about a mile away, in 1969.

A nearby memorial to Henry Joy was donated by his widow in 1938. It was moved to the I-80 summit in 2001 from a remote spot near Creston, between Rawlins and Wamsutter, Wyo., where in 1916 Joy had experienced the most incredible sunset of his life.

The Lincoln Highway has outlived its organizational structures and definitions. In fact, its popularity has increased in the last 35 years. Drake Hokanson’s 1988 book, The Lincoln Highway: Main Street Across America, which helped revive nationwide interest, referred to the highway in the past tense. But especially since Hokanson, Franzwa and other enthusiasts revived the Lincoln Highway Association in the 1990s, the highway now feels much more alive.

Wyomingites rightfully celebrate the Lincoln Highway. But what exactly is being celebrated? Where exactly is it?

Living history

The website of the Lincoln Highway Association recommends that to do a modern tour, a person can mostly take the Interstate. After all, today’s maps label much of I-80 as “the Lincoln Highway.” The website does advise getting off the Interstate and onto city streets in Cheyenne, Sinclair, Rawlins, Rock Springs, Green River, Lyman/Fort Bridger, and Evanston. Most importantly, it urges people to take U.S. 30 from Laramie through Medicine Bow to Walcott Junction.

This nearly-100-mile stretch may be the most famous Wyoming “Lincoln Highway.” As the name of one website of gorgeous photographs says, it was “bypassed by I-80.” It’s almost as if, when we celebrate the Lincoln Highway, we celebrate the act of being bypassed.

In other words, when most people talk about the Lincoln Highway, they mean old U.S. 30. Other than that 100-mile stretch and the “business routes” through cities, people understand that what was bypassed may often now be a frontage road. In a few places, such as the summit between Cheyenne and Laramie, the old road may be as much as a mile from the newer road. In some places it may still be maintained, and drivable, where in other places, it may have faded to nothingness or been obliterated by its replacement.

But “old U.S. 30” is also a moving target. Like the Lincoln Highway, it too was frequently moved, straightened, or improved between its creation in 1926 and the coming of I-80 in the 1960s. For example, in 1935, U.S. 30 between Pine Bluffs and Cheyenne was relocated to reduce distance by five miles and eliminate all railroad crossings. If you want to follow the actual route that Eisenhower did in 1919, you can’t take that “new” U.S. 30, on the route of today’s I-80. You have to take what are now county roads to the north, through downtown Egbert, Burns, and Hillsdale, Wyo.

Likewise, the new U.S. 30 no longer passes through Elmo, Latham or Frewen, Wyo., as the 1931 version of U.S. 30/Lincoln Highway did. The newer roads no longer pass through the heart of Fort Fred Steele, as the 1922 Lincoln Highway (before its rechristening as U.S. 30) did; nor through Baxter, as the 1916 Lincoln Highway did; nor through Blairtown or a stage station south of Bryan named Lone Tree, as the 1913 Lincoln Highway did. You may not have heard of most of these places—but a stickler would say that’s precisely the point. By the 1940s they’d all been “bypassed by U.S. 30.”

Why do we care more about the act of being bypassed by I-80 than by U.S. 30? It’s more recent, in the memory of most baby boomers. It’s more substantial, cutting off that 100-mile stretch. And the construction of the interstate system—with its divided traffic, limited access and limits on commercial activity—feels more momentous than a mere road improvement and relocation. Thus the most important date in today’s conception of the history of Wyoming’s Lincoln Highway may not be its dedication on Oct. 31, 1913, but the opening of I-80 on Oct. 3, 1970.

When we study history, we tell stories that feel relevant in the present day. That’s why history can be so controversial—we’re arguing about what we value today. On the surface, the Lincoln Highway isn’t very controversial, although once you dig in, the story proves ever more complicated. That placid surface reflects a societal agreement: We’re particularly interested in the shift away from the Lincoln Highway, from two-lanes to interstates. As with the shifts away from the Pony Express and open-range cattle drives, we could choose to accomplish our goals with greater speed, efficiency, safety, and comfort. Yet we’re still pondering the change in our shared values implied by that choice.

Resources

Primary sources

- Gladding, Effie Price. Across the Continent by the Lincoln Highway. New York: Brentano's, 1915. Accessed April 5, 2021 at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/33320/33320-h/33320-h.htm.

- Post, Emily. By Motor to the Golden Gate. New York: Appleton and Co., 1916. Accessed April 5, 2021 at https://ia600304.us.archive.org/14/items/bymotortogoldeng00postiala/bymotortogoldeng00postiala.pdf.

- Ramsey, Alice Huyler. Veil, Duster and Tire Iron. Covina, CA: Castle Press, 1961. Republished as Alice’s Drive, with an introduction by Gregory Franzwa. Tucson, Ariz: Patrice Press, 2005.

- Round, Thornton E. The Good of it All. Cleveland: Lakeside Printing Co., 1957.

- Twiss, Clinton. The Long Long Trailer. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1951. Later made into a Lucille Ball movie.

- Van de Water, Frederic Franklyn. The Family Flivvers to Frisco. New York: D. Appleton, 1927.

Secondary sources

- Albany County Historic Preservation Board Tour Guides Project, “The Old Lincoln Highway: A Remarkable Ambition.” Accessed April 5, 2021 at https://visitlaramie.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-Old-Lincoln-Highway-Tour-2017.pdf

- Albany County Historical Society. “Telephone Canyon, new name, old route,” accessed April 5, 2021 at https://www.wyoachs.com/new-blog-1/2019/1/3/telephone-canyon-new-name-old-route.

- Butko, Brian. Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: America's First Coast-to-Coast Road. Centennial edition. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2013.

- “By-Passed: The Lincoln Highway across Wyoming.” Website of historic info and excellent color and historical photographs, accessed April 4, 2021 at https://bypassedbyi80.com/about/.

- Davies, Pete. American Road: The Story of an Epic Transcontinental Journey at the Dawn of the Motor Age. New York: Henry Holt, 2014. Covers the 1919 military motorcade.

- Franzwa, Gregory M. “The Lincoln Highway in Wyoming,” Annals of Wyoming 65, no. 2/3, Summer-Fall 1993, accessed April 5, 2021 at https://ia902802.us.archive.org/35/items/wyomingann6512341993wyom/wyomingann6512341993wyom.pdf, pp. 4-5.

- _________________. The Lincoln Highway in Wyoming. Tucson, Ariz: Patrice Press, 1999. This meticulous guidebook is a major source for this article.

- Hasman, Gregory R.C. “Hotel Tomahawk.” Alliance for Historic Wyoming website, accessed April 4, 2021 at https://www.historicwyoming.org/profiles/hotel-tomahawk.

- Hokanson, Drake. The Lincoln Highway: Main Street Across America. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1988.

- Manning, Tom. “100 Years on the Lincoln Highway.” Wyoming PBS, accessed April 5, 2021 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIW2-bH84u4. A well-done hour-long documentary.

- McConnell, Curt. “A Reliable Car and a Woman Who Knows It”: The First Coast-to-Coast Auto Trips by Women, 1899-1916. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000.

- Pyatt, Kayne. “Standing the test of time: Taggart has owned Pete's Roc n Rye for 50 years.” Uintah County Herald, Oct. 23, 2018, accessed April 5, 2021 at https://uintacountyherald.com/article/standing-the-test-of-time.

- “The Lincoln Highway in Wyoming.” Lincoln Highway Association, accessed April 4, 2021 at https://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org/info/wy/.

- Wallis, Michael. The Lincoln Highway, Coast-to-Coast from Times Square to the Golden Gate: The Great American Road Trip. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007.

- Weingroff, Richard. “From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System.” Federal Highway Administration Highway History, accessed April 5, 2021 at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/numbers.cfm.

- _______________. “The Lincoln Highway.” Federal Highway Administration Highway History, accessed April 5, 2021 at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/lincoln.cfm.

- Wyoming Public Media. “Revisiting The Lincoln Highway's Mid-Century Roadside Gems.” Visits to four sites along the route, for its 100th birthday, accessed April 4, 2021 at https://www.wyomingpublicmedia.org/post/revisting-lincoln-highways-mid-century-roadside-gems#stream/0.

Illustrations

- The photo of the stuck car is from the B. Smart collection at the Laramie Plains Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

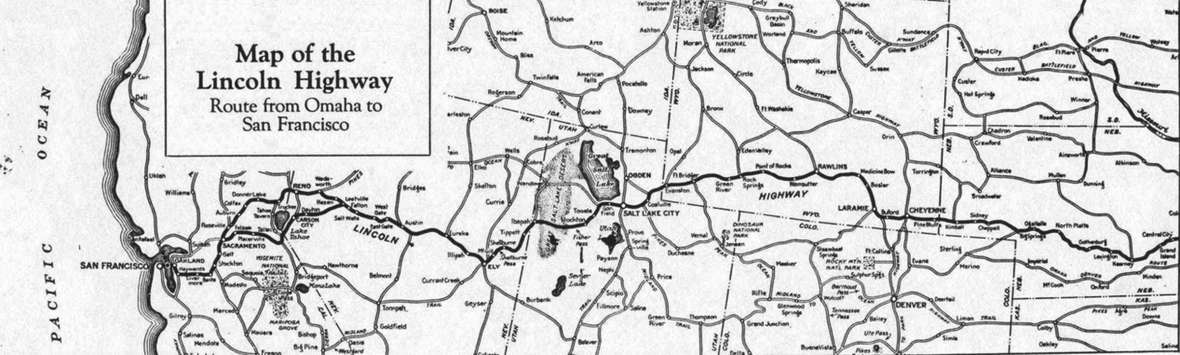

- The map of the Lincoln Highway is from the Federal Highway Administration. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the Lincoln Highway marker is from Wikipedia.

- The photo of Andrew Anderson at the Coyote Springs filling station is courtesy of Nancy Anderson. Used with permission and special hanks.

- The image of the Warwhoop, the souvenir-stand tipi now in Egbert, Wyo., is an early postcard featured in a 2013 story by Erin Dorbin on Wyoming Public Media. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the dedication of the Henry Joy monument is from box 96, folder number 6, Payson W. Spaulding papers, 1886-1980, collection number 01803, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The 1980s photo of a weedy U.S. 30 paralleling I-80 is by Drake Hokanson. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the dedication of the Henry Joy monument is from box 96, folder number 6 of the Payson W. Spaulding papers at the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the unveiling of the Lincoln bust is from the University of Wyoming photo service. Used with permission and special thanks to Marlene Carstens.

- The color photo of the fossil cabin and Texaco pumps at Como Bluff is from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- Doc Thissen’s photo of the Black and Orange cabins at Fort Bridger is from the Uinta County page of his great website, “By-Passed: The Lincoln Highway across Wyoming.” Used with permission and thanks.