- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Near Death of The University of Wyoming

Near Death of the University of Wyoming

Image

From its founding in 1886, the University of Wyoming suffered a lack of funding from the Wyoming Territorial Legislature. Within three years of UW accepting the first students in 1887, new money flowing from the federal government provided the bulk of operating expenses. The funds were tied to the creation of an agriculture school and agricultural experiment stations. Without those, the federal money would not be forthcoming, and the university itself might cease to exist. Surprisingly, this almost happened.

Early Discussions

As early as the first Territorial Legislature of 1869, there was interest in higher education. On December 10, 1869, John A. Campbell, the first governor of Wyoming Territory, signed an act stating that any group of three persons or more could “establish and maintain a college … for the education of youth.”1 No action was taken at the time, but in 1878, Wyoming Territory’s third governor, John Wesley Hoyt, wrote in his annual report to the US Secretary of the Interior: “Steps will soon be needed for the establishment of a college.”2

Image

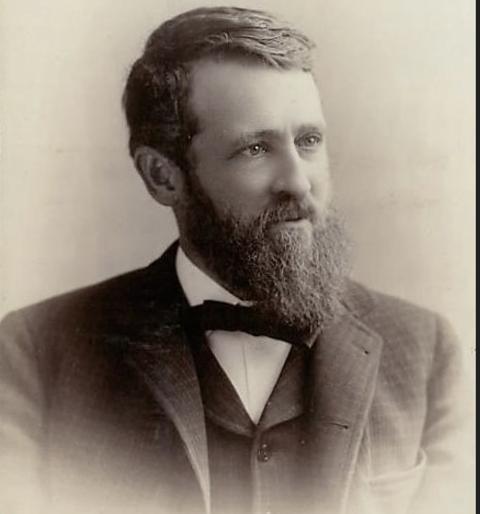

The first known concrete effort came in 1881, when Laramie attorney Stephen Wheeler Downey wrote to the Ames family and suggested that funding and maintaining a university in Wyoming would be a better use of money than building a monument between Laramie and Cheyenne to brothers Oakes Ames and Oliver Ames Jr., Union Pacific Railroad magnates.3

When that did not result in any support from the Ames family, Downey in 1886 tried again, this time through his position in the Territorial House of Representatives. Working with the Laramie County delegation, Downey was able to insert into the so-called Capitol Bill a provision for $50,000 that stated, “There shall be established in this territory an institution under the name and style of ‘The University of Wyoming’ to be located in or near the City of Laramie, in the manner hereinafter named.”4 In addition, the 1886 law authorized a property tax levy of one-quarter (¼) mill to finance university operations.

That, however, would not be enough to meet the goals of the university to expand its faculty, staff, facilities, and course offerings. Financial struggles came to dominate the concerns of the university board of trustees.5 Early on, salaries for faculty were reduced and some positions eliminated. Fortunately, federal funds were potentially helpful. Depending on the enabling federal legislation, some funds were available to Wyoming Territory, but additional funds would not be made available until it became a state.

Role of federal funding

The first of the federal funds for universities came from the Morrill Act of 1862, which, as amended in 1866, would apply to Wyoming when statehood was achieved in 1890. It granted 30,000 acres of federal land to every eligible state for each senator and representative—90,000 in the case of Wyoming. The sale of this land would be used for establishment of colleges “for the benefit of agriculture and Mechanic [sic] arts.”6 While some of this land was sold to fund the university, UW retained portions that continue to generate income to this day through leasing arrangements. After Wyoming became a state, those funds were held by the state treasurer until released to the university in 1905. The delay was primarily due to unresolved disputes over the agricultural college’s location.7

Before Wyoming could access funds from the Morrill Act, an 1881 federal law titled “An act to grant lands to Dakota, Montana, Arizona, Idaho, and Wyoming for university purposes” gave the Wyoming Territory 46,080 acres of federal lands to be sold for use of a future university.8 Wyoming Territory took four years to identify the lands, a timeline extended by administrative transitions between territorial governors, the complexity of selecting lands across all seven counties, and a multi-stage federal approval process requiring correspondence between Governor Warren and the Secretary of the Interior. When that process was finally complete, income from these lands was initially insignificant.9

The immediate realization of federal funding came in 1887 with passage of the Hatch Act. The act provided $15,000 per year for colleges that instituted “agricultural experiment stations” for the benefit of citizens of any territory or state. The state and the university board of trustees moved to collect the funds, with the first batch arriving in 1891. Efforts by Wyoming’s congressional delegation eventually prodded the federal government to give Wyoming an additional $30,000 in a form of reimbursement for the years 1888–1890.10 In his November 14, 1890, address to the legislature, Governor Francis E. Warren said that those funds should be passed from the federal government to the territory and then on to the University of Wyoming.11

Finally, the Second Morrill Act of 1890 provided an additional $15,000 per year to colleges and universities that statutorily prohibited the exclusion on the basis of “color.”12 Wyoming qualified because Article VII Section 10 of the 1889 Constitution of the State of Wyoming, ratified by vote of its citizens and in effect when Wyoming became a state, prohibited discrimination in any public school based on “color.”13

Trouble brewing

Although the university’s financial picture was greatly improved and the institution’s future seemingly secured, ominous clouds were on the horizon. The trouble began in 1886 with the passage of the aforementioned Capitol Bill. Albany, Laramie, and Uinta County members of the legislature worked together to pass the legislation, which resulted in the capitol building in Cheyenne and the university in Laramie. They also worked together to fund an “insane asylum” in Evanston and a “deaf, dumb and blind” school in Cheyenne.

The remaining counites of Carbon, Fremont, Johnson, and Sweetwater were not offered any public institution that would bring jobs to their cities and towns. The Carbon County Journal was particularly offended and called the process “outrageous.”14 Fremont and Johnson counties believed there was a way to possibly rectify the situation. Representatives from each county introduced bills in the legislature to create an agriculture college separate from the university. If approved, it would also move the critical federal funding from the university to the new college, creating a serious blow to UW.

On February 1, 1888, Senator Loucks of Johnson County introduced a bill to create an agriculture college in Sheridan.15 That bill was recommended “do not pass” by the Senate Committee of the Whole and died without further action. Another attempt was made in the final session of the territorial legislature in early 1890. On January 24, Senator J.L. Stotts, representing Converse and Crook counties, introduced a bill to create an agriculture school in Buffalo.16 That effort also did not make it out of the Senate.

Image

Efforts in the first session of the newly created state of Wyoming, though, would yield more success. Fremont County Representative Eugene Amoretti Sr., often noted as the founder of Lander, introduced a bill in the House of Representatives on December 10, 1890, to establish the “Wyoming Agricultural College” and to determine its location.17 Two days later, The Fremont Clipper quickly declared that the intention of the bill was to locate the institution in Lander.18 The same day The Boomerang in Laramie noted an ongoing effort by legislators from “the northern part of the state” to have the critical Hatch Act funds diverted away from the university.19 Indeed, on December 13, 1890, the House Committee of the Whole addressed a proposal that contradicted Warren’s statement that federal monies should go the university. The move recommended that the funds could go to any agricultural college that may be established.20 The bill, which would have bolstered the Amoretti bill and hurt the university, was defeated.

Three days later, the other Fremont County representative, Robert Hall,21 introduced an additional act that complemented the Amoretti bill. Hall’s bill stated that the establishment and location of an agriculture college was to be determined by vote of the citizens of the territory.22 Within the week, The Buffalo Echo23 claimed that the agriculture college belonged in Buffalo, because Johnson County is “the prize agricultural county of Wyoming.”

As the two bills worked their way through the legislature, the result was an act that had the effect of establishing an agricultural college in a location other than Laramie. It is unclear what stance the delegation from Albany County took, because most votes in committee were not recorded by member. However, The Fremont Clipper24 declared on December 26, 1890, that both the Albany and Laramie County delegates supported Lander as the location. This may have been reasonable given the language of the act when it passed.

The act had two parts. First, an agriculture college would be established, and the location had to be below 5,500 feet elevation, automatically eliminating Cheyenne, Evanston, and, crucially, Laramie.25 This meant that when the “new” agriculture college was established, federal funds sustaining university operations would no longer go to UW, likely sounding the death knell of the institution. Interestingly, a review of the university board of trustees’ minutes of the period did not mention the act nor any actions that could be taken to avoid a catastrophe.26

The second part of the act required that the location of the school would be determined by vote of the state’s citizens at the 1892 election. Acting Governor Amos Barber signed the bill on January 10, 1891. It was published as Chapter 92 of the session laws of the State of Wyoming passed by the first state legislature of 1890/91.27

Support for an agriculture college in Lander

Lander, Sheridan, and Buffalo were already announcing that they preferred the agricultural college to be located in those towns.28 Additionally, Sundance, Casper, and Douglas placed their communities in the ring.29 As the election neared, the competition became intense. On election day, November 8, 1892, The Cheyenne Daily Sun recapped interviews with leading citizens from those towns. The tenor of the debate was generally positive with each interviewee extolling the qualities of their nominees.30 There was, though, an underlying current of meanness. Mr. Maurice [sic: Morris in original] Heinz of Sundance, while declaring Lander had the advantage, said of the Douglas nomination: “I do not believe in the location of the agriculture college in Converse county, as they cannot raise anything up there except sage brush and prairie dogs.”31

Lander, with its small population of 534, won the election with the aid of large vote majorities in Albany and Laramie counties.32 Suddenly, the agriculture college and accompanying federal funding appeared to be leaving Laramie. All that remained was for the legislature to provide the funds for operations and the construction of facilities. When that happened, the university would be very hard pressed to continue operations with only state funding. Two days after the election, The Boomerang put it succinctly: “Many feel as though the removal of the college from this city would eventually result in crippling the university of this state.”33

The situation looked bleak for UW. When the legislature convened in January 1893, it did so with much contention between the Democrats and the Republicans. It began in the wake of the Johnson County War (a range war between large cattle companies and homesteaders), a dispute over who was governor, and a deadlock over electing a U.S. senator.34 These would slow proceedings in the legislature and impact legislative action on the Lander college bills. Additional financial pressure was evident with the beginning of a recession and many bank failures.35 The recession would likely influence any decision on funding the Lander agricultural college.

Increased anxiety was felt in Laramie when Fremont County Representative James Farlow introduced a bill in the House on January 14, 1893, which called for an appropriation of $75,000 for construction of the Lander college.36 That bill was assigned to the House Ways and Means Committee of which Stephen Downey (Albany) was a member along with representatives from Fremont, Johnson, Carbon/Natrona, and Crook/Weston counties, all of whom were strong supporters of an agriculture college not affiliated with the university. Additionally, Farlow introduced a separate bill two days later hoping to revisit the stipulation that federal funds in support of agriculture could only go to the university.37 It was assigned to the House Public Buildings Committee, which Farlow chaired.

The appropriations bill was recommended as “do pass” by the Ways and Means Committee. On February 8, committee member Downey, who was also president of the university board of trustees, offered a lengthy minority report that opposed the appropriation on five points.38 First, the appropriation would require new taxes on already overly burdened taxpayers. Second, Lander was far from any railroad, making it hard to get to. Third, Lander had a small population and therefore few local students who could attend. Fourth, the university was capable of providing instruction in the agricultural arts and could easily do the job. Fifth, the bill was unconstitutional (likely referring to Article VII Section 15 of the Wyoming Constitution, which designated UW as the sole beneficiary of lands donated by the federal government and any grants received therefrom). Downey’s minority report fell on deaf ears.

Later that day, the bill was considered by the House Committee of the Whole. The Boomerang reported that representative W.D. Pickett of Fremont County spoke at length in favor of the bill.39 Speaker of the House L.C. Tidball, Downey, and at least two other members spoke against the bill as either too costly or not necessary. Pickett then attacked Downey’s stand on the basis that he was the president of the university board of trustees. Given the prestige of Speaker Tidball, The Boomerang wrote that the bill would be defeated, or a substitute bill would be forthcoming.40 The bill went back to the Ways and Means Committee.

Despite The Boomerang’s prediction, the bill with a reduced appropriation of $32,000 passed second reading in the House on February 9.41 On third reading, Downey unexpectedly voted for the bill and then immediately asked for a revote. Perhaps he thought he could change enough minds that the bill would be defeated. The other three Albany County representatives voted against the bill. Downey never got the revote, and the bill was sent to the Senate.42

Image

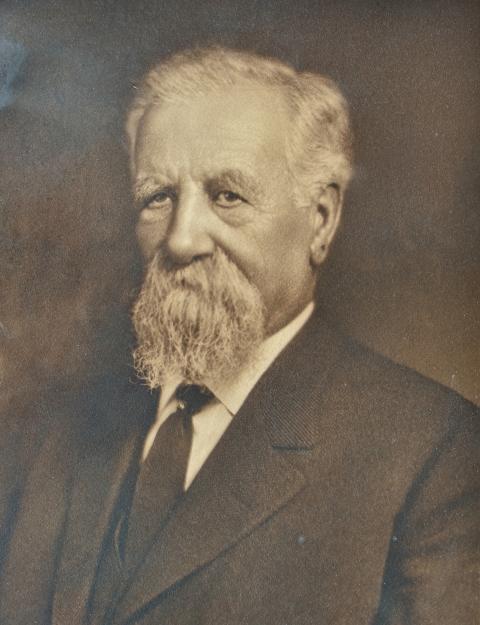

The Cheyenne Daily Leader threw its weight behind the bill upon its arrival in the Senate.43 On February 15, the Senate Committee on Buildings and Institutions invited esteemed citizens J.L. Torrey of Fremont County and M.C. Brown of Albany County to make remarks on the bill. The Boomerang reported that Torrey stressed that the election that sent committee members to the Senate also authorized the agriculture college to be located in Lander. He stated that the Senate should honor the wishes of the voters. Brown argued that there was no need for a separate institution in Lander as “the state university fulfilled all the requirements for the state.”44

Image

There were no members from Fremont County on the committee, and it took the group only one day to report the bill back without recommendation. No further action was taken by the Senate. Perhaps financial concerns due the budding recession, a very lengthy inconclusive debate over the election of the next US senator, or Brown’s words swayed them. In any case, the funds to build the Lander college were not provided for.45 It would seem Lander’s plan was dead, and the university’s federal funding secured.

1895–1901: Continuing attempts to fund a Lander college

But the Fremont County legislative delegation was not about to give up the quest for an agriculture college in Lander. They knew that the 1891 law and the 1892 vote required the state to build the college. In the 1895 session of the legislature, they forged ahead with a plan to secure what the law required. J.L. Torrey, now the speaker of the House, joined his fellow Fremont representative Edward Ranney and introduced a bill to fund the college through a property mill levy on January 12.46

The bill was referred to the Committee of the Whole on February 2. It was recommended “do pass,” and a week later it was read for the third time but failed. Torrey immediately moved for a revote, and when taken it passed. Significantly, Downey, who was still president of the university board of trustees, had voted no on the bill but changed his vote to approve the bill before voting closed.47 As was the case in 1893, no explanation could be found in contemporaneous newspapers or minutes of the board of trustees for Downey’s action. The board did not even meet between June 1894 and March 1895.48 Most actions concerning university operations in the interim were handled by the board’s executive committee, and it may have addressed the issue.49 After a thorough search of records, the author was unable to locate any discussions and subsequent actions during the interim, if such records exist. The approved bill was passed to the Senate, which reported back to House on February 3 that the bill was postponed indefinitely, and no further action was taken.

Subsequently, the Laramie Weekly Sentinel expressed the sentiment of Laramie residents toward the 1895 bill when it wrote on February 16: “The fact is that during the first half of the week a condition of uneasiness closely bordering upon panic has prevailed among the faculty and students at the university, as well as among our citizens generally. It was freely asserted and generally believed that the proposed action of the legislature would cause the closing of the institution even before the end of the year.”50 It went on to report that the Senate had killed the bill.

The Fremont County representatives, however, were determined to pursue the matter. After all, the clear reading of the 1891 law and the results of the 1892 vote should place an agriculture college in Lander. A bill in the 1897 legislature for the Lander college failed on third reading in the House when three members did not show up for the vote.51 In the 1899 legislature, a bill for funding to build the agriculture college in or near Lander passed the House, but failed in the Senate.52 Similar results befell the effort in 1901.

Efforts to establish an agriculture college in Lander eventually fail

In 1903, a bill was introduced to repeal the section of the 1891 law that required an agriculture college separate from UW, and it called for a new vote on a location for the college.53 The bill died in the Senate. A new wrinkle occurred that same year. Wealthy Lander resident Phillip Wisser died in June, and his will adjudicated in December 1904 contained a bequest of land and money to build the “Wyoming Agricultural College” in Lander. The college trustees requested the federal funds that were going to UW be instead given to the newly formed private college. Wyoming treasurer Henry Hay refused the request.54

Image

The legislature believed it could end any threat the Lander college posed to the university by simply repealing the 1891 law that called for the creation of a separate agriculture school. Lawmakers repealed the law in the 1905 legislative session, but they were mistaken in believing the issue was resolved.55 When the new state treasurer, William Irvine, continued to send federal monies to the university, the Lander group approached the Wyoming State Supreme Court asking it to force the treasurer to direct the funds to the proposed Lander school.56 The Wyoming Supreme Court denied that request on January 31, 1906. The Lander group then appealed to the US Supreme Court. The high court denied the group’s request on May 13, 1907, noting that federal funding could not go to a private entity.57

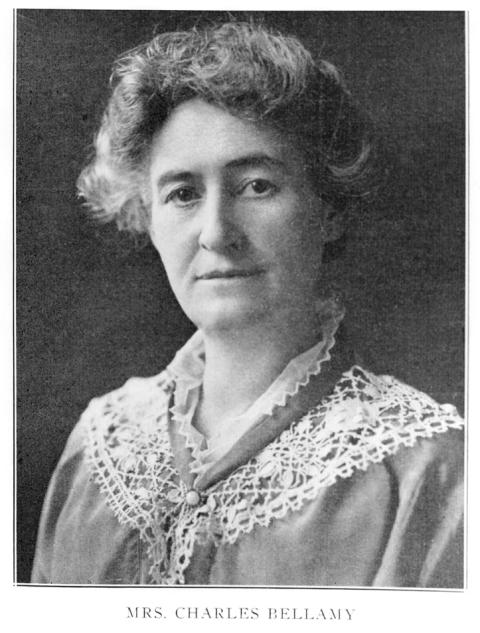

Once more, it seemed that the university was free from any challenge to move the agriculture college to Lander. Yet, in 1911, despite the court decisions, Fremont County representatives again tried to convince the legislature to fund a college in Lander. Albany County representative Mary Godat Bellamy headed off the challenge by agreeing to support Fremont County positions on bills before the legislature.58 Finally, the issue was put to rest, and what is now called the University of Wyoming College of Agriculture, Life Sciences, and Natural Resources is alive and well in Laramie today.

Image

Editor's note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, whose support helped make the publication of this article possible.

Images Courtesy of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, the Wyoming State Archives, the Fremont County Museum, and Peter Boutin.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Lander, Wyoming: The Fremont Clipper, December 26, 1890, p. 2, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Barlow, Bill, ed. “Political Assassination.” Douglas Wyoming: Bill Barlow’s Budget, November 16, 1892, p. 1, col. 3. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- BlackPast. “(1890) Second Morrill Act.” BlackPast.org, September 14, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/second-morrill-act-1890

- Bouton, Thos J., ed. “Sitting Bull Killed: The Great Disturber Forever Quieted by His Own People [the agricultural college discussion is under this headline as a stand-alone paragraph].” Buffalo, Wyoming: The Buffalo Echo, December 20, 1890, p. 1, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Carroll, Jno. F., ed. “Come Together: The Bill Should Pass.” Cheyenne, Wyoming: The Cheyenne Daily Leader, February 12, 1893, p. 2, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- _____ “Gambling Goes [the agricultural college discussion is under this headline as a stand-alone paragraph].” Cheyenne, Wyoming: The Cheyenne Daily Leader, February 7, 1893, p. 3, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- _____ “The State Victory.” Cheyenne, Wyoming: The Cheyenne Daily Leader, November 10, 1892, p. 2, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- “College Controversy.” Cheyenne, Wyoming: Cheyenne Daily Sun, November 8, 1892, p. 1, col. 6. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Constitution of the Proposed State of Wyoming: Adopted in Convention at Cheyenne, Wyoming. September 30, 1889. Cheyenne, Wyoming: The Cheyenne Leader Printing Co., 1889. The Library of Congress’ Early State Records Project, 2024. Discover LLMC, 2025. https://discover.llmc.com

- Council Journal of the Tenth Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne on the Tenth Day of January, 1888. Cheyenne, Wyoming: Bristol & Knabe Printing Co., Printers and Bookbinders. 1888. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3066769&seq=1

- Council Journal of the Eleventh Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne on the Fourteenth Day of January, 1890. Cheyenne, Wyoming: The Cheyenne Daily Leader Stem Book Print. 1890. HathiTrust, 2023. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3066772&seq=1

- Friend, Jno C., ed. “The Capital.” Rawlins, Wyoming: Carbon County Journal, February 27, 1886, p. 2, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- General Laws, Memorials and Resolutions of the Territory of Wyoming, Passed at the First Session of the Legislative Assembly, Convened at Cheyenne, October 12th, 1869. Cheyenne, W. T., S. Allan Bristol, Public Printer, Tribune Office, 1870. HathiTrust, 2025. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433007185063&view=1up&seq=311

- “Hatch Act of 1887. Act of 1887 Establishing Agricultural Experiment Stations.” University of New Hampshire, College of Life Sciences and Agriculture, 2025. https://colsa.unh.edu/new-hampshire-agricultural-experiment-station/hatch-act-1887

- Hayford, J. H. “Editorial.” Laramie, Wyoming: Laramie Weekly Sentinel, February 16, 1895, p. 1, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- _____ “Legislative Proceedings.” Laramie, Wyoming: Laramie Weekly Sentinel, February 18, 1888, p. 2, col. 3. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- House Journal of the Tenth Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wyoming. 1888. Cheyenne, Wyoming: The Leader Book and Job and Printing House, 1888. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3066770&seq=5

- House Journal of the Third State Legislature of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne on the Eighth Day of January, 1895. Cheyenne, Wyoming, Daily Sun Book Print, 1895. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884137&seq=69&q1=college

- House Journal of the Fourth State Legislature of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne on the Eleventh Day of January, 1897. Cheyenne, Wyoming, Sun-Leader Printing House, 1897. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884139&seq=5

- House Journal of the Fifth State Legislature of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne, Wyoming, on the Tenth Day of January, 1899. Laramie, Wyoming, Chaplin, Spafford & Mathison, Printers, 1899. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884140&seq=5

- House Journal of the Sixth State Legislature of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne, Wyoming, on the Eighth Day of January, 1901. Laramie, Wyoming, Chaplin, Spafford & Mathison, Printers, 1901. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884141&seq=1

- House Journal of the Seventh State Legislature of Wyoming, Convened at Cheyenne, Wyoming, on the Thirteenth Day of January, 1903. Laramie, Wyoming, Chaplin, Spafford & Mathison, Printers, 1903. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884142&seq=7

- House Journal of the Eighth State Legislature of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne, Wyoming, on the Tenth Day of January, 1905. Sheridan, Wyoming, Sheridan Post Company, Printers, 1905. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884143&seq=5

- “It is Worse Than Ever: Legislative Business.” Laramie, Wyoming, The Daily Boomerang, February 9, 1893, p. 1, col. 2. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Jay L. Torrey Photograph. Box Number 7, Folder 2, Jay L. Torrey papers, 1802–1941. Collection Number 00585, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

- Journal of the House of the First Legislative Assembly of the State of Wyoming. First Day Hall of the House of Representative, Cheyenne, Wyoming, Nov. 12, 1890. Discover LLMC, 2025. https://discover.llmc.com

- Journal of the House of the Second Legislative Assembly of the State of Wyoming. First Day Hall of the House of Representatives, Cheyenne, Wyoming, January 10th, 1893. Discover LLMC, 2025. https://discover.llmc.com

- Journal of the Senate. Second Session, First Day, Senate Chambers, Cheyenne, Wyo., Jan–10–1893. Discover LLMC, 2025. https://discover.llmc.com

- “Legislative Proceedings: Numerous Interesting Measures Proposed.” Lander, Wyoming: The Fremont Clipper, December 12, 1890, p. 2, col. 2. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Moeller, G. E. A., ed. and pub. “Legislative Notes.” Buffalo, Wyoming: Buffalo Voice, January 26, 1901, p. 2, col. 2. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Morrill Act (1862). Milestone Documents: US National Archives and Records Administration, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/morrill-act

- Nye, Bill, ed. “Adjourned Sine Die: First State Legislature Adjourned Sunday Morning at 5:30.” Laramie, Wyoming: The Daily Boomerang, January 12, 1891, p. 4, col. 4. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- _____ “Legislative Doings: The Grant Investigation Committee Reports: In Committee of Whole.” Laramie, Wyoming: The Boomerang, December 10, 1890, p. 1, col. 5. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- _____ “The College Fund.” Laramie, Wyoming: The Daily Boomerang, December 12, 1890, p. 1, col. 5. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- _____ “The State Legislature: The University.” Laramie, Wyoming: The Boomerang, December 18, 1890, p. 1, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Revised Statutes of Wyoming, in Force January 1, 1887. Cheyenne, Wyoming, The Daily Sun Steam Printing House, 1887. Discover LLMC, 2025. https://discover.llmc.com

- Richardson, W. R., “The Agricultural College.” Sundance, Wyoming: Sundance Gazette, November 11, 1892, p. 4, col. 1. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- Senate Journal of the Third State Legislature of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne on the Eighth Day of January, 1895. Cheyenne, Wyoming, Daily Sun Book Print, 1895. HathiTrust, 2025. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015068469884&seq=3

- Senate Journal of the Fifth State Legislature of Wyoming. Convened at Cheyenne, Wyoming, on the Tenth Day of January, 1899. Laramie, Wyoming, Chaplin, Spafford & Mathison, 1899. HathiTrust, 2025. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015068469876&seq=1

- Senate Journal of the Seventh State Legislature of the State of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming, Chaplin, Spafford & Mathison, Printers, 1903. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015068469850&seq=7

- Session Laws of the State of Wyoming, Enacted by the First State Legislature. Convened at Cheyenne on the Twelfth Day of November. Cheyenne, Wyoming, The Daily Sun Publishing House, 1891. HathiTrust, 2024. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d022885267&seq=375&q1=college

- Slack, E. A. “College Controversy: A Spirited Rivalry Between Wyoming’s Prosperous Towns.” Cheyenne, Wyoming: The Cheyenne Daily Sun, November 8, 1892, p. 1, col. 6. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- “State Ex Rel. Wyoming AGR. College v. Irvine.” Justia Law, 2019. https://law.justia.com/cases/wyoming/supreme-court/1906/116344.html

- “The Agriculture College.” Laramie, Wyoming: The Daily Boomerang, February 15, 1893, p. 3, col. 3. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- “The Agricultural College: Several Cities are Making a Lively Contest Here.” Laramie, Wyoming: The Daily Boomerang, November 10, 1892, p. 12, col. 4. https://wyomingnewspapers.org

- University of Wyoming Board of Trustees Minutes. Box Number 22, University of Wyoming. Board of Trustee Records, Collection Number 500,000, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

- Wyoming v. Irvine, 206 U.S. 278 (1907).” Justia: U.S. Supreme Court, 2025. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/206/278/

Secondary Sources

- Clough, Wilson O. A History of the University of Wyoming, 1887–1937. Laramie, Wyoming: Laramie Print. Co., 1937.

- Hardy, Deborah. Wyoming University: The First 100 Years, 1886–1986. Laramie, Wyoming: University of Wyoming, 1986.

- Helton, Jennifer. “Mary Godat Bellamy, Wyoming’s First Woman Legislator.” WyoHistory.org, December 6, 2024. https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/mary-godat-bellamy-wyomings-first-woman-legislator

- Rezneck, Samuel. “Unemployment, Unrest, and Relief in the United States During the Depression of 1893–97.” Journal of Political Economy, University of Chicago Press, January 1, 1970, 324–324. https://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v61y1953p324.html

- Roberts, Phil. “UW’s Land Grant: Choosing Sections for UW’s Land Grant: Surveyor F. O. Sawin’s Project, 1886.” Wyoming Almanac, April 3, 2021. https://wyomingalmanac.com/?p=958

- Van Pelt, Lori. “John E. Osborne and the Logjammed Politics of 1893.” WyoHistory.org, February 6, 2016. https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/john-e-osborne-and-logjammed-politics-1893

- Viner, Kim. West to Wyoming: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Stephen Wheeler Downey. Laramie, Wyoming, Laramie Plains Museum Association, 2017.

Footnotes

[1] “General Laws, Memorials and Resolutions of the Territory of Wyoming, Passed at the First Session of the Legislative Assembly, Convened at Cheyenne, October 12th, 1869,” Article II Section 1 (HathiTrust, Session Laws of the State of Wyoming, Session 1, 2002), 9–10. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433007185063&view=1up&seq=….

[2] Wilson O. Clough, A History of the University of Wyoming 1887–1937 (Laramie, Wyoming: Laramie Print. Co., 1937), 12.

[3] Kim Viner, West to Wyoming: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Stephen Wheeler Downey (Laramie, WY: Laramie Plains Museum Association, 2017), 189. A discussion of the letter was found in the Grace Raymond Hebard papers, Collection 400008, Box Number 35, Folder 2, at the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

[4] Clough, 14; Revised Statutes of Wyoming, in Force January 1, 1887, Chapter 42, Section 3698, 781, HathiTrust Digital Library, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112105420873&seq=7.

[5] Deborah Hardy, Wyoming University: The First 100 Years, 1886–1986 (Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming, 1985), 34.

[6] Full text of the act can be found at “The Second Morrill Act (1890),” BlackPast.org, September 14, 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/second-morrill-act-1….

[7] Hardy, 26.

[8] Full text of the act can be found at “Hatch Act of 1887,” New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station, https://colsa.unh.edu/new-hampshire-agricultural-experiment-station/hat….

[9] Phil Roberts, “UW's Land Grant,” Wyoming Almanac, April 3, 2021, https://wyomingalmanac.com/?p=958.

[10] Hardy, 36.

[11] “Territorial House Journal 1890,” in House Journal of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wyoming (1890), 46, LLMC Digital, 2013, https://llmc.com/OpenAccess/docDisplay5.aspx?textid=76183644.

[12] Second Morrill Act (1890).

[13] Wyoming, Constitution of the Proposed State of Wyoming: Adopted In Convention At Cheyenne, Wyoming, September 30, 1889, Article VII, Section 10 (Cheyenne, Wyo.: Cheyenne Leader Printing Co., 1889), 37, https://llmc.com/OpenAccess/docDisplay5.aspx?textid=76112983.

[14] Carbon County Journal (Rawlins, WY), February 27, 1886, 2.

[15] “Territorial House Journal 1888,” in House Journal of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wyoming (1888), reformatted from the original, LLMC Digital, 2013, 79, https://llmc.com/OpenAccess/docDisplay5.aspx?textid=76183644.

[16] “Territorial House Journal 1890,” 47.

[17] “State House Journal 1890,” House Journal: Reformatted from the original and including, Senate Journal of the ... Legislative Assembly of the State of Wyoming ... (2013): 171, https://llmc.com/OpenAccess/docDisplay5.aspx?textid=76183644. Note: There were two sessions of the Wyoming Legislature that conducted business in 1890. The first was convened while Wyoming was still a territory and the second after Wyoming obtained statehood.

[18] The Fremont Clipper (Lander, WY), December 12, 1890, 1.

[19] The Boomerang (Laramie, WY), December 12, 1890, 1.

[20] “State House Journal 1890,” 225.

[21] Fremont Clipper Dec. 26, 1890, 2 .

[22] “State House Journal 1890,” 271.

[23] Buffalo Echo (Buffalo, WY), December 20, 1890, 1.

[24] Fremont Clipper, December 26, 1890, 2.

[25] “State House Journal 1890,” 528.

[26] Minutes of the University of Wyoming Board of Trustees, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Collection Number 500000, 54–55.

[27] “Session Laws of the State of Wyoming Passed by the State Legislature 1890/91,” 373, HathiTrust, 2002, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d022885267&seq=375&q1=c….

[28] Clough, 61.

[29] Bill Barlow’s Budget (Douglas, WY), November 16, 1892, 1.

[30] Cheyenne Daily Sun (Cheyenne, WY), November 8, 1892, 1.

[31] Ibid.

[32] The Sundance Gazette (Sundance, WY), November 11, 1892, 4.

[33] Boomerang, November 10, 1892, 12.

[34] Lori Van Pelt, “John E. Osborne and the Logjammed Politics of 1893,” WyoHistory.org, 2016, https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/john-e-osborne-and-logjammed-po….

[35] Samuel Rezneck, “Unemployment, Unrest, and Relief in the United States During the Depression of 1893–1897,” Journal of Political Economy 61, no. 4 (1953): 324–345, https://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v61y1953p324.html.

[36] “State House Journal 1893,” in House Journal of the Legislative Assembly of the State of Wyoming (1893), reformatted from the original, LLMC Digital, 2013, 50, https://llmc.com/OpenAccess/docDisplay5.aspx?textid=76184191.

[37] “State House Journal 1893,” 59.

[38] “State House Journal 1893,” 191.

[39] Boomerang, February 9, 1893, 1

[40] Ibid.

[41] Clough, 61.

[42] “State House Journal 1893,” 268–269.

[43] The Cheyenne Daily Leader (Cheyenne, WY), February 12, 1893, 2.

[44] Boomerang, February 15, 1893, 3.

[45] “State House Journal 1893,” 16.

[46]“House Journal of the State Legislature of Wyoming 1895,” HathiTrust, 2009, 69, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884137&seq=69&q1=college.

[47]“House Journal of the State Legislature of Wyoming 1895,” 353.

[48] Minutes of the University of Wyoming Board of Trustees, 212–213.

[49] Hardy, 27.

[50] Laramie Weekly Sentinel (Laramie, WY), February 16, 1895, 1.

[51] “House Journal of the State Legislature of Wyoming 1897,” HathiTrust, 2009, 467, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884139&seq=5. NOTE: Hardy reports this on p. 42 but erroneously states the vote failed by one.

[52] “Senate Journal of the State Legislature of Wyoming, Convened at Cheyenne on 1899,” HathiTrust, 2002, 244, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015068469876&seq=1.

[53] “Senate Journal of the State Legislature of Wyoming, Convened at Cheyenne on 1903,” HathiTrust, 2002, 126, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015068469850&seq=7.

[54] Hardy, 42–43.

[55] “House Journal of the State Legislature of Wyoming 1905,” HathiTrust, 2009, 91, 238, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2884143&seq=5.

[56] Hardy, 42; State ex rel. Wyoming Agr. College v. Irvine, 14 Wyo. 318 (1906).

[57] Hardy, 43; Wyoming v. Irvine, 206 U.S. 278 (1907).

[58] Jennifer Helton, “Mary Godat Bellamy, Wyoming's First Woman Legislator,” WyoHistory.org, December 6, 2024, https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/mary-godat-bellamy-wyomings-fir….

![Image of Eugene Amoretti’s original bill. Handwritten text of bill: "HB No. 40 by Mr. Amoretti. 'For an act providing for the establishment of certain Educational Institutions to be known respectively as "The Wyoming Agricultural College" and "The Wyoming Normal School," and to provide for the location and government of said Institutions, and for the [illiegible] to be given and for other purposes. Read the first time and referred to committee No. 10.'](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2025-07/5%20Original%20Amoretti%20bill%20Wyoming%20House%20Journal%201890.jpg?itok=W9f4XTuA)