- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Reborn In Robes: The Second Klu Klux Klan In Wy...

Reborn in Robes: The Second Klu Klux Klan in Wyoming, 1921-1930

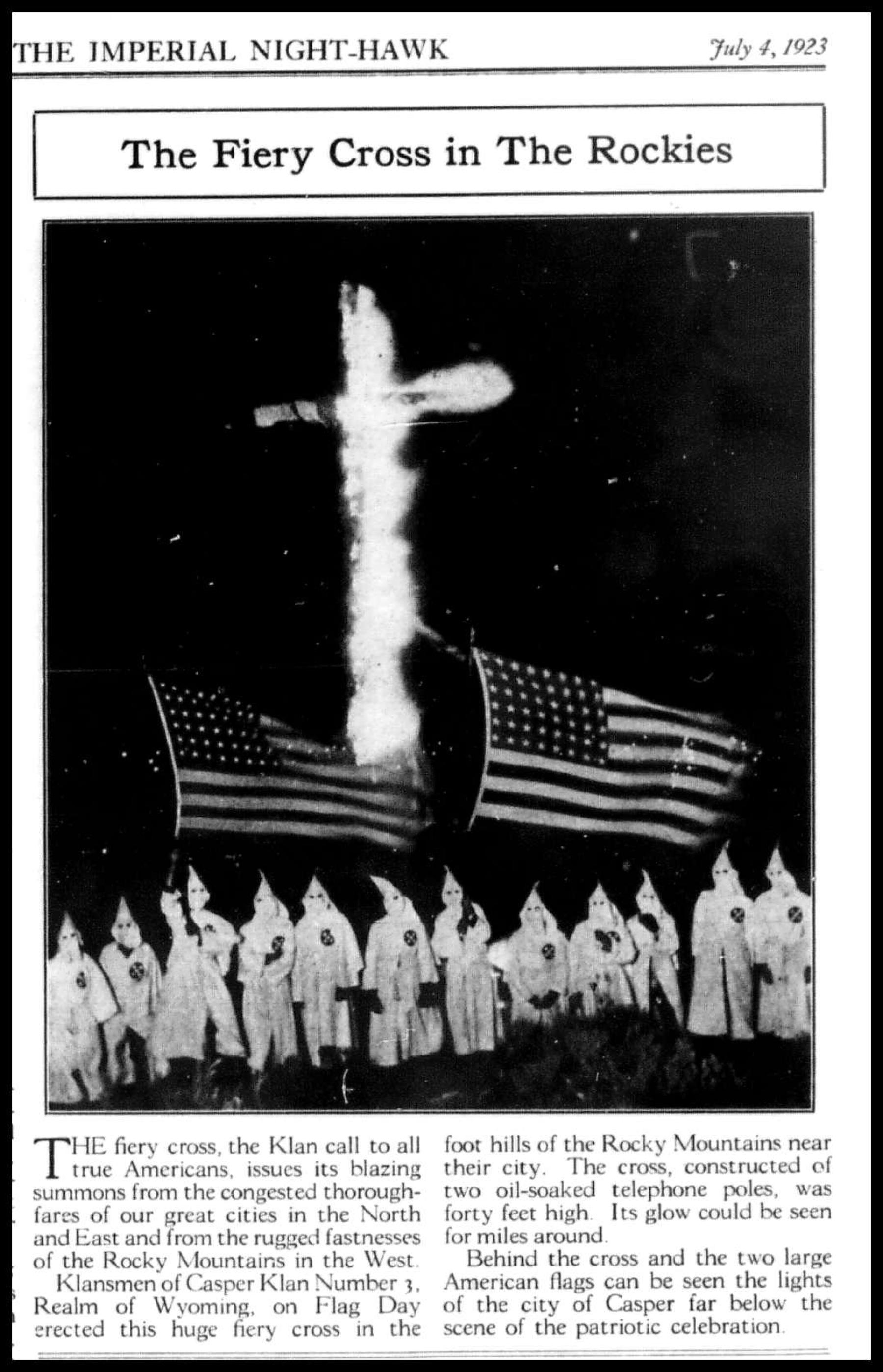

“Here’s a mark for other states to aim at! In the Realm of Wyoming there is a Klan in every town of more than 1,000 population and some in the smaller towns,” boasted The Imperial Night-Hawk, a leading newspaper of the Second Ku Klux Klan, on May 9, 1923. This bold claim challenges the conventional understanding of the Klan’s presence in Wyoming.

Wyoming historian T.A. Larson once suggested the Second Klan was not as active in Wyoming as elsewhere. In his book History of Wyoming, he explains: “In the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan organized a few units in the Big Horn Basin and Cheyenne. They burned crosses and painted the letters KKK on front porches to intimidate primarily Roman Catholics, foreign-born and native, and secondarily, blacks and Jews.” While the Klan’s statement in The Imperial Night-Hawk may have been exaggerated, evidence suggests the Klan had a stronger and more widespread presence in Wyoming than previously assumed.

The Rise of the Second Klan

Established in 1915, the Second Klan rapidly expanded across America in the 1920s, becoming a nationwide nativist force that encompassed 48 states. During this period, it attracted more than two million members, with a particularly strong presence in Northern states. Diverging from its Reconstruction-era predecessor, this Klan broadened its list of perceived adversaries to include Roman Catholics, Jews, immigrants, those deemed “non-Anglo-Saxon,” and anyone suspected of communist sympathies.

The Klan’s appeal lay in its capacity to connect rhetoric with real-world circumstances, rallying Anglo-Saxon Protestants around tangible concerns related to race, religion, “immorality,” and ethnicity. A pivotal focus was “One Hundred Percent Americanism,” a concept embodied by the KKK’s national leader, Hiram Wesley Evans: “Foreigners come to America not out of love for this country but to better themselves... They can never become genuine true one hundred per cent Americans.”

Recruiting in the Rockies

In spring 1921, Imperial Wizard William Simmons met with high-level recruits in Denver, which subsequently served as the headquarters for the KKK’s Northwestern Domain, encompassing Colorado, Utah, Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. By summer 1921, Kleagles (Klan recruiters) were spreading throughout the region.

Douglas residents opened their newspaper on June 9, 1921, to learn that Kleagles were in their community. The Douglas Budget reported, “It is said a number of well known [sic] citizens of this city have interested themselves in the organization.” Similar reports appeared in other Wyoming newspapers as Klan chapters, or “klaverns,” were established that summer in Powell, Riverton, and soon after in Evanston, Greybull, Green River, Rock Springs, Pinedale, Laramie, Saratoga, Encampment, Lingle, Torrington, Wheatland, and other towns.

Recruitment efforts received an unexpected boost from a syndicated exposé of the Klan by the New York World in September 1921. Contrary to the newspaper’s intentions, the coverage sparked interest rather than deterrence. The Moorcroft Democrat praised the Klan, declaring, “There is something appealing in this idea of an all-American organization.”

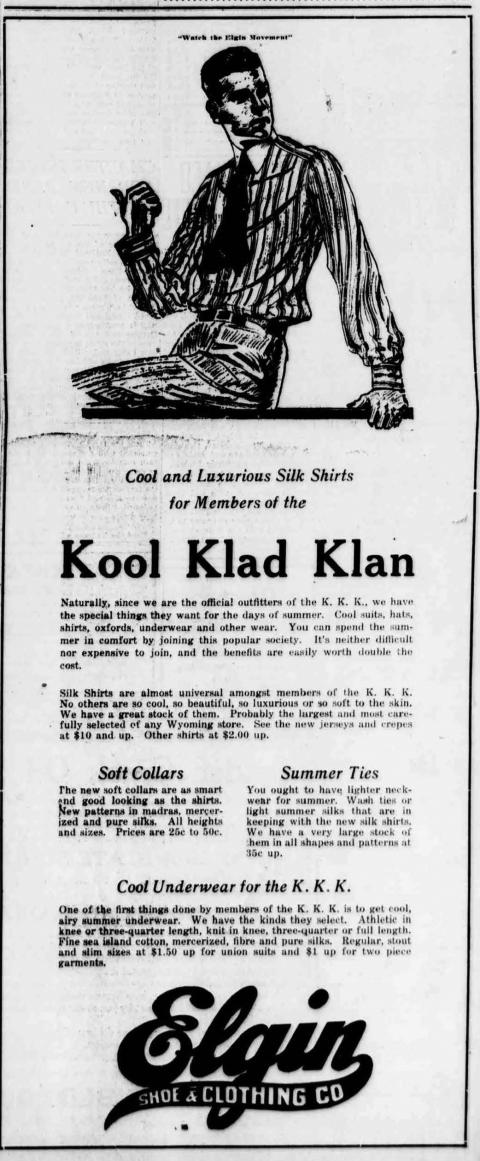

The Klan’s recruitment strategies were targeted. Masons were a primary focus due to their influence in society and history of anti-Catholic sentiments. Medical professionals, including doctors, nurses, and public health reformers, were enlisted to endorse white supremacy and support scientific racism, particularly eugenics. Many Protestant ministers were attracted by the Klan’s rhetoric and dues exemption, either joining the Klan or supporting it from their pulpits.

Fertile Ground for Recruiting

Wyoming was primed for acceptance of the hooded order. A prevailing sense of unease existed among some white Protestant residents regarding the state’s changing demographics. By 1920, foreign-born whites made up 13 percent of Wyoming’s total population of 194,402. Catholics, many of them Irish immigrants, grew to 10 percent of the population with strongholds in cities like Cheyenne, Rock Springs, and Casper.

After 1914, Wyoming leaders increasingly blamed immigrants for social problems, enacting discriminatory laws that banned firearm ownership and restricted employment. Schools and civic organizations pushed coercive “Americanization” programs to eliminate foreign influences.

Prohibition’s unpopularity and lack of enforcement in Wyoming also paved the way for the Klan. Despite adopting Prohibition before the national 18th amendment, enforcing it proved difficult, with widespread flouting of the laws. This climate of ineffective and selective law enforcement created resentment and perceptions of lawlessness that aligned with the Klan’s emphasis on imposing order and morality.

Beyond alcohol, anxieties brewed over traditional values erosion and “modern” threats like revealing fashions, public displays of affection, and provocative dancing. As self-declared arbiters of virtue, Klansmen promised to constrain perceived social decay and restore upright citizenship.

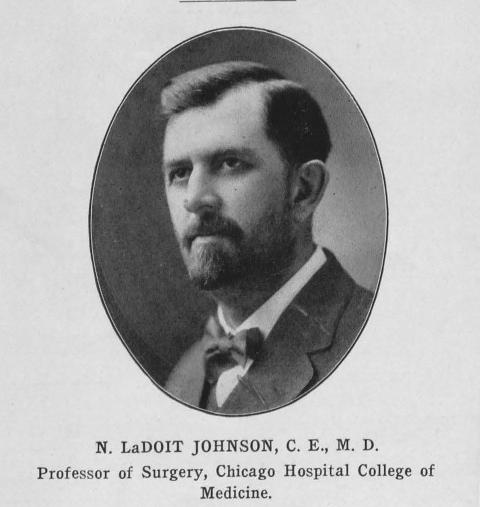

Image

Dragon and Kleagle: Wyoming Klan Leaders Johnson and Dickson

Dr. LaDoit Johnson of Casper became the leader of Wyoming’s Klan. His path to becoming Grand Dragon seemed incongruous given his successful medical career in Chicago. Born in 1869, Johnson had been a prominent surgeon and medical educator in Chicago before inexplicably moving to Casper in 1919. He set up the L.D. Johnson Clinic by early 1921 and became integrated into the community by joining fraternal orders and investing in local businesses.

Under Johnson, organizing efforts in Casper progressed rapidly. By September 1921, the Casper Daily Tribune reported, “From what little is known it is estimated that the [Klan] roll contains 100 to 200 names.”

The emphasis on “cleaning up” Casper soon appeared. In late summer and October 1921, the klavern was suspected of arson when two roadhouses in the city’s Sandbar district mysteriously burned to the ground. Anti-Catholicism was also a component of the Casper Klan as they sought to intimidate the Irish Catholic community, with confrontations occurring outside St. Anthony's Church.

In 1921 or 1922, Dr. Johnson was appointed Grand Dragon of the Realm of Wyoming by national Klan leadership. In this role, he coordinated state activities, communicated directives from national headquarters, and oversaw events and collection of dues. Johnson’s prominence extended beyond Wyoming when he was appointed to the Klan’s national finance committee, a role he retained until August 1924.

Another significant figure was George Dickson, Jr., who held the position of Wyoming State Kleagle. He had arrived in Douglas from Canada in 1889 and eventually opened a successful hardware store there. As kleagle, his role involved recruitment and overseeing Klan expansion statewide.

Embedding the Klan in Wyoming

The Klan embedded itself throughout Wyoming over several years. In Cheyenne, an issue of The Fiery Cross in August 1923 declared that “a terrific downpour of rain did not stop the initiation ceremonies of the Ku Klux Klan” and “the Klan is the strongest fraternal organization in this part of the state.”

A Buffalo klavern had been organized by February 1922 and offered to cooperate with officials in suppressing moonshine sales. Around the same time, a Sheridan klavern was also organized, with members sending threatening notes to local business owners.

In Riverton, about 150 new members participated in a dramatic outdoor initiation ceremony illuminated by a burning cross, vividly demonstrating the Klan’s growing appeal.

The Klan in Evanston made state news due to its dramatic appearance. In March 1923, Sheriff L.D. Christenson and Uinta County Prosecuting Attorney Dick Westra were summoned to a meeting place and confronted by robed Klansmen. A spokesman warned, “Klansmen’s eyes and Klansmen’s ears are upon you and every county and city official, silent and unknown.”

Evidence of the Klan’s entrenchment appeared in communities across the state, from Worland to Thermopolis to Greybull. The organization’s presence provoked varied responses, from casual acceptance to fierce opposition, as demonstrated by Greybull businesswoman Lizabeth Wiley, who ran for mayor in 1924 explicitly to combat Klan influence—and won.

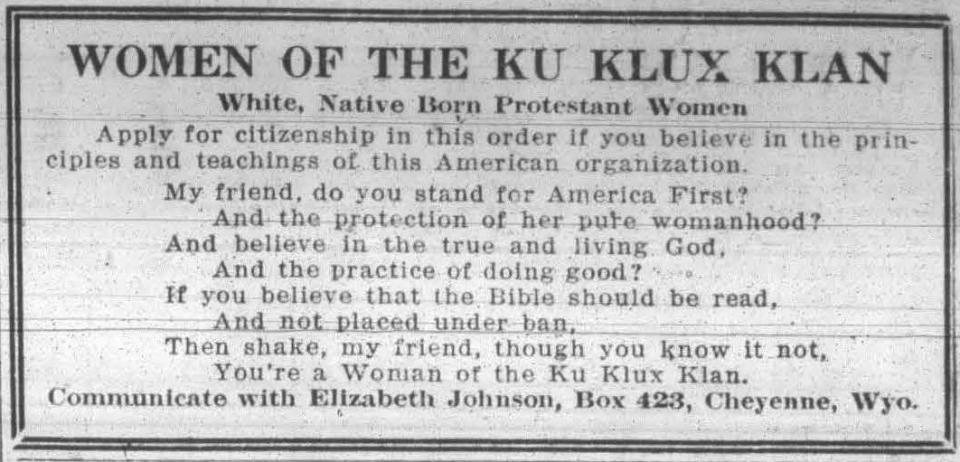

Women of the Ku Klux Klan

Although less emphasized than the men’s organization, Wyoming women also participated actively. In 1924, the “Women of the Ku Klux Klan” (WKKK), a national auxiliary organization, appeared publicly in Wyoming, donating to local charities and even sparking rivalries over formal organization. Women’s auxiliaries amplified the Klan’s social reach, reinforcing its focus on Protestantism, morality, and anti-Catholic sentiment.

The WKKK in Wyoming functioned independently but cooperatively with male klaverns, establishing their own officers, rituals, and bylaws. Their activities mirrored the men’s priorities: promoting Prohibition enforcement, public education based on Protestant ideals, and Americanization programs. WKKK members played key roles behind the scenes in organizing social and charitable activities, while also appearing prominently in parades, public ceremonies, and events, demonstrating their commitment to the Klan’s causes both privately and publicly.

KKK’s Religious Charitable Front

The Second Klan nationally sought to burnish its image through charitable works. Declaring that “America is Protestant and so it must remain,” the KKK glorified the “old time religion” and admonished its members to attend church regularly.

As proof of their devotion, masked Knights frequently appeared unannounced before congregations to make well-publicized donations. In December 1921, the pastor of Sheridan's Congregational Church received a twenty-dollar bill along with a letter explaining Klan tenets. That same month, the Buffalo klavern gifted money to three churches for “Christmas charity.”

On September 24, 1922, a “tall knight of the klan [sic], hooded and robed” shocked the pastor and congregation at Casper’s First Baptist Church by arriving during services, handing over an envelope containing one hundred dollars for a children’s gymnasium, and then silently departing.

Evidence of the Klan’s deep infiltration into Casper’s Protestant churches surfaces in a history of the local First Christian Church, which notes that Reverend Roy Hildebrand was said to be the only Protestant pastor who was not a member. The book comments that “many business and professional people belonged [to the Klan] and approximately 50% of the congregation of First Christian Church were sympathetic.”

Imposing Spectacles Galvanize Support

After a social event drew in likely recruits, mass initiation ceremonies would typically be held at a local farm, ranch, or park. The Riverton Review described a late July 1924 event where about one hundred fifty initiates entered the order in an open-air meeting on Griffey Hill, attracting townspeople who were drawn to the site by a large burning cross.

Wyoming klaverns, especially those on the state border, could also partake of events with their fellows across state lines. In summer 1924, Wyoming Klan members traveled to Sidney, Nebraska, for a large recruitment event where two thousand attendees were directed to a remote valley by burning crosses and robed Knights.

Cross burnings were signature rituals of the Second Klan nationwide, and Wyoming saw its share of this form of promotion and intimidation. On Independence Day in 1923, cross burnings were visible in Riverton and Rock Springs. Buffalo residents were stunned on Christmas night in 1925 by a forty-foot cross burning on a hill, accompanied by a blast of dynamite to alert sleeping residents.

Hidden in Plain Sight: The Klan’s Cryptic Ways

“One of the first duties of a Klansman is to obey the rules and regulations of this great American order of which we are so justly proud. At the head of the list of the laws of the Klan stands that of absolute secrecy,” reminded The Imperial Night-Hawk. The KKK operated covertly, maintaining secret membership rolls and discouraging members from openly advertising their affiliation.

The secretive nature of the Klan was often remarked upon by Wyoming newspapers. The editor of the Greybull Standard observed, “The thing about this organization which causes considerable comment seems to be that so many think they know who does and who does not hold membership and yet are not sure about anybody but themselves.”

Despite the Klan’s secrecy, Wyoming participants were at times revealed, particularly upon their death. In April 1922, five persons in KKK robes laid a wreath upon the casket of Edward J. Sexton, a doctor in Gillette, leaving a note that read: “In respect to our brother Klansman, who stood with us for 100 per cent Americanism, protection of our homes, children, and pure womanhood.”

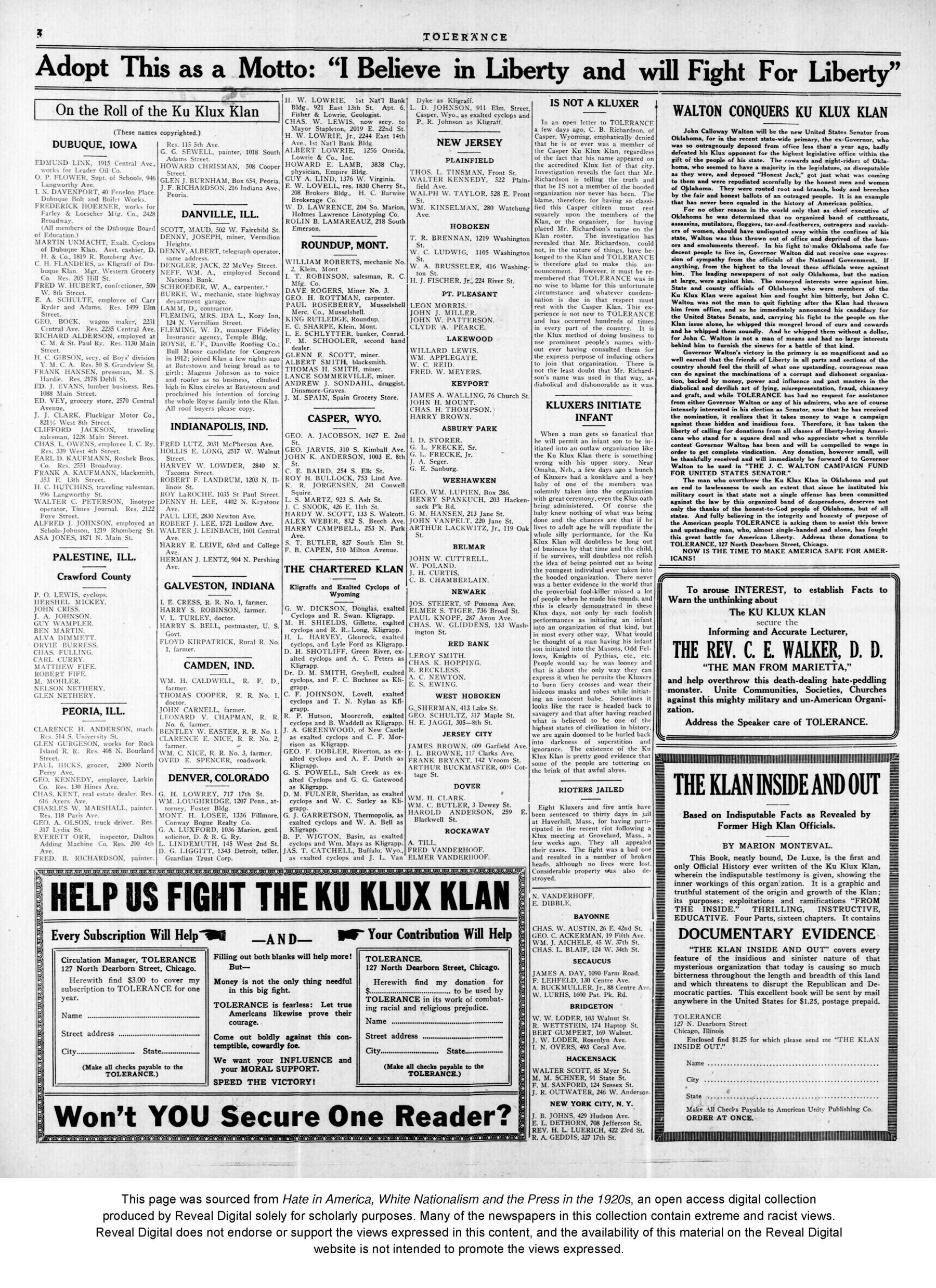

The most explosive means of revealing Klan members was done by the American Unity League (AUL), a Chicago-based group that countered the Klan. The AUL employed various strategies to infiltrate the Klan and published extensive lists of Klan members in its newspaper, Tolerance. In Casper, members of the Knights of Columbus hired AUL leader Patrick O’Donnell, who joined the Klan there and obtained members’ names, which were then published in Tolerance during 1924.

Klan’s Influence in Wyoming Politics

The Klan sought to gain political power openly to advance its agenda. In December 1923, Klan leaders published a chart assessing U.S. senators’ Klan-friendly inclinations. Wyoming senator Francis E. Warren was labeled an “Old Guard wheel horse” and viewed unfavorably, while Senator John B. Kendrick was considered one of the “highest class Democrats.”

The Klan influenced the 1924 election season, both nationally and in Wyoming. At the Democratic Convention, Kendrick and the Wyoming delegates helped narrowly defeat a plank denouncing the Klan, earning praise in The Imperial Night-Hawk for casting “a vote for Americanism.”

Nellie Tayloe Ross, elected that year as the first female U.S. governor, had a nuanced relationship with the KKK. Despite her late husband denying permission for a Klan convention at the 1923 Wyoming State Fair, Ross claimed later that the KKK had no significant influence during her campaign.

In the 1926 gubernatorial race, Republican candidate Frank C. Emerson faced questions about Klan affiliation. A letter to Emerson from supporter J.A. Whiting reveals the complexity of the issue, noting that one Republican County Chairman demanded Emerson publicly denounce the Klan, while others advised him to address questions only privately to avoid alienating Catholic voters.

In Casper, where the Klan was most deeply entrenched, its influence penetrated various levels of power. In the 1922 elections, campaign ads referenced alleged Klan memberships, and accusations flew between candidates. Later, critics like the Casper Herald accused officials with likely KKK ties of obstructing justice to protect allies, citing specific cases of suspected favoritism.

Twilight of Klankraft

By 1925, growing scandals began damaging the Klan’s credibility. Outbreaks of violence tied to the Klan in states like Ohio, Illinois, and Massachusetts led to critical coverage in national newspapers. Closer to home, violence on the part of Colorado Klan leader John Galen Locke made news when he and other high-ranking members were charged with kidnapping and conspiracy. Even more damaging was the scandal involving Indiana Grand Dragon David C. Stephenson, who was convicted of kidnapping, raping, and murdering a woman.

At the Wyoming level, the blow came from the AUL’s exposure of confidential Klan membership lists of the Casper group. Grand Dragon Dr. L.D. Johnson resigned shortly after Tolerance exposed his affiliation on August 24, 1924. George W. Dickson Jr. succeeded him but could not stem the decline.

By the end of the decade, the Klan’s relevance had dissipated almost completely in Wyoming. Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans’ highly symbolic move to publicly discard Klan masks and hoods in 1928 would have applied just as much to places like Douglas, Rock Springs, and Laramie as any other declining klaverns. Hopes of a lasting Invisible Empire wielding political and social clout inside the state had vanished alongside the wider order’s credibility and membership nationwide.

Editor’s Note: For a more in-depth look at the second Ku Klux Klan’s presence in Wyoming, see Waggener’s articles in the Winter 2024 issue of Annals of Wyoming: “KKK Country: How Wyoming Embraced the Ku Klux Klan” and “Dragon and Kleagle: Wyoming Klan Leaders Johnson and Dickson.” Visit a Wyoming county library to read past editions of the Annals of Wyoming. If you are interested in subscribing to the Annals of Wyoming, please reach out to editor Charles E. Rankin at cerankin@ou.edu for more information.

Sources

- Alexander, Charles C. “Kleagles and Cash: The Ku Klux Klan as a Business Organization, 1915-1930.” The Business History Review 39, no. 3 (Autumn 1965): 348-367.

- Antonovich, Jacqueline. “White Coats, White Hoods: The Medical Politics of the Ku Klux Klan in 1920s America.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 94, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 439-469.

- Cardoso, Lawrence A. “Nativism in Wyoming, 1868-1930: Changing Perceptions of Foreign Immigrants.” Annals of Wyoming 58, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 20-38.

- Chalmers, David M. Hooded Americanism: The First Century of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1965. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1965.

- David, J. Tom. Glimpses of Greybull’s Past: A History of a Wyoming Railroad Town from 1887 to 1967. Baltimore: Gateway Press, 2004.

- David, Robert “Bob” B. Unpublished Memoir. Robert “Bob” B. David Historical Collection, Coll. No. NCA 01.v.1987.01, Casper College Archives and Special Collections, Casper, WY.

- Doherty, Linda L. An Irish Legacy: Casper’s Catholic Community, 100 Years of Faith. Casper: St. Anthony’s Parish Council, 1987.

- First Christian Church. First Christian Church: Our First 50 Years, 1921-1971. Casper: The Committee, 1971.

- Fry, Henry P. The Modern Ku Klux Klan. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1922.

- Gerlach, Larry R. Blazing Crosses in Zion: The Ku Klux Klan in Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press, 1982.

- Goldberg, David J. “Unmasking the Ku Klux Klan: The Northern Movement Against the KKK, 1920-1925.” Journal of American Ethnic History 15, no. 4 (Summer 1996): 32-47.

- Goldberg, Robert Alan. Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981.

- Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition. New York: Liveright Publishing, 2017.

- Hendrickson, Gordon Olaf. Peopling the High Plains: Wyoming’s European Heritage. Cheyenne: Wyoming State Archives and Historical Dept., 1977.

- Horowitz, David A. Inside the Klavern: The Secret History of a Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. The Ku Klux Klan in the City. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. 2nd ed., rev. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

- McGovern, Patrick A. History of the Diocese of Cheyenne. Cheyenne: Diocese of Cheyenne, 1941.

- McVeigh, Rory. The Rise of the Ku Klux Klan: Right-Wing Movements and National Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

- Rea, Tom. “Booze, Cops, and Bootleggers: Enforcing Prohibition in Central Wyoming.” WyoHistory, July 16, 2016, accessed April 10, 2025, at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/booze-cops-and-bootleggers-enforcing-prohibition-central-wyoming. <

- United States Department of Commerce. Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920 — Population, Wyoming — Composition and Characteristics of the Population. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921.

- Wallace, Jerry L. “The Ku Klux Klan in Calvin Coolidge’s America.” Coolidge Blog, Calvin Coolidge Foundation, July 14, 2014, accessed April 15, 2025, at https://coolidgefoundation.org/blog/the-ku-klux-klan-in-calvin-coolidges-america/.

- The Imperial Night-Hawk. May 9, 1923; May 2, 1923; May 30, 1923; June 13, 1923; July 9, 1924; July 25, 1923; July 2, 1924; Oct. 24, 1923; Jan. 23, 1924.

- The Fiery Cross. Indiana edition. Aug. 10, 1923; Aug. 24, 1923; Sept. 28, 1923; Jan. 18, 1924; Feb. 15, 1924; March 14, 1924; Dec. 14, 1923 (Michigan State edition).

- Tolerance. August 10, 1924; August 24, 1924.

- Various Wyoming newspapers, 1919-1928. See endnotes for specific issues.

Sites Associated with the Second KKK

Historic Downtown Casper: Casper’s central business district retains important original 1920s structures that reflect the city’s oil boom prosperity and civic development during the Klan’s active years. Notable buildings include the Rialto Theater (1921) and the Turner-Cottman Building (1924). These landmarks offer a glimpse into the environment in which the Klan sought influence.

CY Ranch Area (Casper vicinity): The CY Ranch, located about 10 miles west of Casper, was owned by the prominent Carey family and served as the site of a major 1923 Klan ceremony, including a mass “naturalization” event following a statewide Klan convention (known as a Klorero”). Although now privately owned and not open for public tours, the surrounding area remains historically significant for understanding how the Klan organized public displays of power during its peak years in Wyoming.

Historic Downtown Sheridan and Trail’s End: Sheridan’s downtown retains original 1920s-era buildings that provide context for the period of Klan activity in northern Wyoming. In addition, Trail’s End, the historic home of U.S. Senator and former Governor John B. Kendrick, offers visitors insight into Wyoming’s political leadership during the 1920s, when debates over the Klan’s influence played out at both state and national levels. Located at 400 Clarendon Avenue, the Kendrick Mansion is open to the public as a museum. https://trailsend.org/

Uinta County Courthouse (Evanston): 225 9th Street, Evanston, Wyoming 82930. Built in 1873 and remodeled in the early 20th century, the courthouse is notable for its role in the 1923 incident where Sheriff L.D. Christenson and Prosecuting Attorney Dick Westra were confronted by robed Klansmen. The structure remains a tangible connection to this dramatic confrontation between local officials and Klan members.

Mount Pisgah Cemetery (Gillette): 804 S. Emerson Avenue, Gillette, Wyoming 82716. Mount Pisgah Cemetery reflects local community history and is the resting place of longtime Gillette physician Dr. Edward J. Sexton (1860-1922). In 1922, a Klan-associated funeral ceremony took place here, marked by masked mourners placing a wreath at a gravesite.

Historic Downtowns Across Wyoming: Many Wyoming towns still retain historic downtown buildings from the early twentieth century, reflecting the civic, economic, and social environments in which the Ku Klux Klan briefly flourished. Walking through districts in communities like Casper, Sheridan, Cheyenne, and others offers visitors a tangible sense of the small-town prosperity and cultural tensions of the 1920s.