- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Sheridan County, Wyoming

Sheridan County, Wyoming

Sheridan County, Wyo. Where else can you find polo ponies, working ranches and farms, spectacular mountains, sparkling streams and vast prairies, a prestigious sanctuary for artists and writers and a history rich in American Indian lore, outlaws, pioneers, miners and Old West dude ranches?

Early history

Today’s Sheridan County descends from the spine of the Bighorns in northern Wyoming eastward over rolling hills, verdant pastures and on across the drier plains. The region has appealed to American Indians, trappers, military men, pioneers and settlers alike.

The westward expansion of European settlements from the East started a falling-dominoes effect: tribes leaving their Eastern and Midwestern homes only to push other tribes before them. The Shoshone, whose ancestors had lived in the Bighorn foothills for thousands of years, were supplanted by the Crow, who in turn were pushed along by the Arapaho, Sioux and Cheyenne during the course of the 18th and 19th centuries.

“Crow country is exactly in the right place,” said Crow Chief Arapooish, speaking to Robert Campbell of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in the 1830s. “It has snowy mountains and sunny plains; all kinds of climates and good things for every season. When the summer heat scorch [sic] the prairies, you can draw up under the mountains, where the air is sweet and cool, the grass fresh, and the bright streams come tumbling out of the snow banks.”

Trappers and traders, however, weren’t quite as poetic about the Bighorns. Montreal-based François-Antoine Larocque was the first non-Indian visitor and found the foothills full of wildlife in 1805. “The Woods along the Rivers are as thickly covered with Bears Dung as a Barn door is that of the Cattle, large Cherry trees are broken down by them in Great number. The Indians kill one or two almost every Day,” he wrote.

Seventy-one years later, Gen. George Crook and 1,000 troops used the meadows along Goose Creek as a staging area during the 1876 summer campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne. Crook’s continually shifting Camp Cloud Peak provided forage for horses and a pleasant refuge for soldiers who saw fierce fighting at Rosebud Creek in Montana, and then heard the unsettling news that Gen. George Armstrong Custer and his Seventh Cavalry had been wiped out by the Indians a few days’ ride to the north at the Little Big Horn.

Settlement

The next year, the Indian wars were over, with the tribes driven onto reservations in Dakota and Montana territories. Parts of northern Wyoming Territory that had been vigorously contested were now open to settlement by trappers, ranchers, hay contractors for the U.S. Army, farmers, stage company employees and occasional outlaws.

Wyoming Territory, organized in 1869, started with four, and later five, vast county units, each running from the southern to northern border. As settlements sprouted up, locals began pushing for smaller counties, with county seats closer to where they lived. As the political process worked itself out, the original counties were repeatedly divided, with pieces traded back and forth. Sheridan County emerged as a smaller chunk of Johnson County.

Though the town of Sheridan would become the largest community in the area, it was not the first. That honor went to Big Horn City, founded in 1878 by U.S. Army scout Oliver Hanna and friends. The town, with several stores, a newspaper and hotel, was located nearer to Johnson County’s Buffalo than Sheridan was, and in 1888, competed with Sheridan for the designation of county seat.

Sheridan ultimately got the nod for county seat because it was the biggest town, was incorporated early as a municipality and was more centrally located to the rest of the county. Sheridan enjoyed the sweet spot location-wise, with abundant water at the confluence of two streams and excellent forage for livestock.

In addition, business leaders encouraged competition as a way to encourage growth. Sheridan founder John Loucks, who opened the town’s first general mercantile store, invited J.H. Conrad to shift his general merc from Buffalo to Sheridan. Then and now, more businesses attract more customers. Loucks intercepted blacksmith Henry Held, on his way to Yellowstone, and convinced him to set up shop in Sheridan.

Perhaps most critically, Sheridan wasn’t too close to the mountains, so steep grades would not scare away the railroad companies then looking at northern Wyoming. Three companies--the Northern Pacific, the Cheyenne and Northern and the Burlington and Missouri--had surveyed northern Wyoming by 1889. The 1892 arrival of the Burlington and Missouri, better known over the years simply as the Burlington, solidified Sheridan’s dominance over competing towns.

Railroads, coal mines and railroad ties

While all roads, trails, stagecoach lines and railroads led to the city of Sheridan, there was a lot more to Sheridan County than its county seat.

Railroad stops popped up along the Burlington, as the line was built from Gillette northwest to Sheridan in 1892, and farther northwest to Huntley, Mont., in 1894. In southeastern Sheridan County, there were the towns of Arvada, Kendrick, Leiter, Clearmont, Ulm and Wyarno. West of Sheridan, the railroad ran through or near the coal camps of Kleenburn and Monarch, and the ranch communities of Ranchester and Parkman before entering Montana. Residents of communities along the rail line had jobs with the railroad or easier access to markets for their livestock and crops.

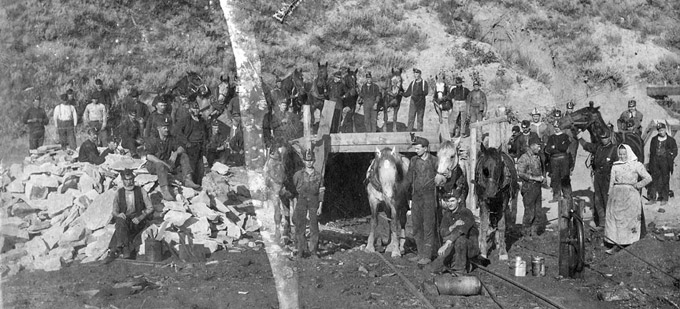

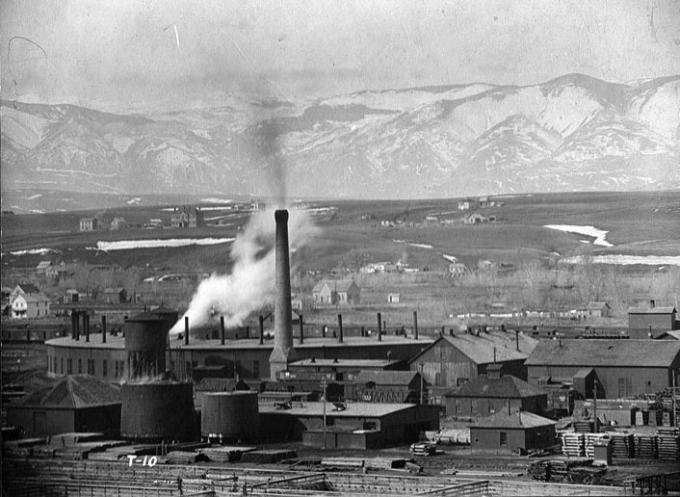

Coal mines were developed to fuel the steam locomotives that ran through the county. Layers of coal were easily visible in the hills north and west of Sheridan, so farmers and ranchers could easily obtain coal for fuel. Large, underground coal mines–Monarch, Carney, Acme, Kooi and Dietz–employed hundreds of workers, while smaller mines employed mere handfuls. Coal camps and company towns sprang up to house the miners’s families. Consolidation of mining properties followed in the early 1920s, until most operations were owned by the Sheridan-Wyoming Coal Company or Peabody Coal.

By the early 1950s, the coal mines were all closed, as coal became eclipsed by natural gas used for homes and industry or diesel used for locomotive fuel. The county’s coal camps and towns either vanished entirely or were much diminished. Much of the coal in Sheridan County remains unmined because underground coal mining cannot compete in scale and price with the open-pit mining in the Powder River country farther east.

Sheridan County is also the location of a vanished mining town, Bald Mountain City, on top of the Bighorns near present Burgess Junction, founded in pursuit of an 1890s gold boom that never quite materialized.

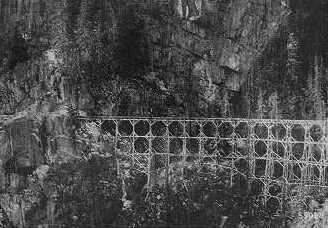

The arrival of the Burlington encouraged the growth of tie-hack camps in the mountains. Lumbermen—tie hacks—cut down trees, and then floated the logs in flumes down to the Tongue River above Dayton. From there the logs floated down the river to Ranchester, where they were cut into ties at a sawmill and loaded onto the railroad.

Early ranching—and polo

Early ranching saw a strong British influence, focused on raising horses, Hereford cattle, and polo ponies. Sheridan County’s Goose Creek valley was—and is—idyllic for raising horses: good water, good forage and, with its low elevation at the foot of the Bighorn Mountains, relatively mild winters.

In the late 1800s, Capt. F.D. Grissell of British India’s famed cavalry regiment, the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers opened a polo pony operation on his IXL Ranch near Dayton. Two Scottish brothers, Malcolm and William Moncreiffe, set up a polo field and pony breeding operation near Big Horn in 1893. English nobility like Oliver Wallop, who later became the 8th earl of Portsmouth, as well as monied scions of Eastern and Midwestern universities and businesses, were drawn to the area as well.

Late in the 1890s, the region’s stock raisers sold 22,550 horses for the British cavalry, then engaged in the Boer War in South Africa.

These early Brits and their prosperous American friends began a tradition of landed wealth that continues to affect the culture of Sheridan County. Bradford Brinton, from an Illinois family that had done well in the farm-implement business, bought the Quarter Circle A Ranch outside Big Horn from the Moncreiffes in the 1920s. The Bradford Brinton memorial is open to the public today, preserving Brinton’s house and art collection. And Malcolm Wallop, grandson of the 8th earl, was elected from Wyoming three times to the U.S. Senate, beginning in 1978.

For a time after World War I, the Circle V Polo Company in Big Horn was recognized as the top polo operation in the world. Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, on a North American tour, stopped in Sheridan in October 1984 to visit the Wallops and buy polo ponies. Today, the Big Horn Equestrian Center and the Flying H Polo Club host matches all summer long. And some Wyoming cowboys have proven to be great polo players.

Irrigation

Irrigation projects started in the late 1800s with the Park Reservoir used for watering alfalfa crops. In the 1930s, Lake DeSmet water was ditched out to the Clearmont area, helping to grow wheat and sugar beets. Those crops prompted the local development of flour and sugar mills, which survived until the 1960s.

Today, the region east of Sheridan is used mostly for livestock grazing, while west of Sheridan, circle pivot sprinklers provide irrigation for alfalfa crops.

Tangentially related to agriculture is the rise of dude ranches in Sheridan County. Due to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show and an eastern press fascinated by cowboys and Indians, easterners often sought western adventures. Westerners found they could make money offering the experiences of horseback riding, cattle hazing and eating chuckwagon dinners.

Several dozen dude ranches sprang up in Sheridan County. Some attracted national fame. Most prominent by far was Eatons’ Ranch, founded in 1904 in the foothills of the Bighorns west of Sheridan near Wolf, Wyo. Guests included movie stars Cary Grant and Will Rogers; artists Hans Kleiber and Charlie Russell; and authors Mary Roberts Rinehart and Will James.

Visitors could come for a week or a summer. Many dudes and dudettes became so devoted that they chose to retire in Sheridan County, or tried to find any excuse to move to their beloved Bighorns permanently.

“Eatons’ Dude Ranch played a significant role in the development of Sheridan County. Many Eaton guests which moved to Sheridan County, or married local cowboys, provided fresh blood and resources in the county. This had a positive influence on Sheridan County both culturally and in the areas of business and philanthropy,” wrote Sheridan County Commissioner Tom Ringley, author of a book about the historic ranch.

Other communities

Besides Sheridan, incorporated towns in Sheridan County include Ranchester, Dayton and the much smaller Clearmont. Big Horn and Story are larger than Clearmont, but remain unincorporated. Other communities include Arvada and Parkman, and the hamlets of Banner, Leiter, Wolf and Wyarno.

History has shown quite a few more towns, according to the Sheridan County Extension Homemakers Council, which produced the Sheridan County Heritage Book in 1983. Written by residents and based on personal journals, the book lists towns and hamlets no longer on current maps, but still familiar to locals. From east to west, there’s Passaic, Oxus, Slave, Huson, Ulm, Verona, Springwillow, Carroll, Dewey, Park, Beckton, Bingham, Kooi, Woodrock Bear Lodge, Rockwood, Ohlman, Slack, Burks and Walsh.

Ucross, originally a ranch and crossroads on Clear Creek 10 miles west of Clearmont, is also on the map, not as a town but as a 20,000-acre retreat for award-winning painters, printmakers, photographers, writers, composers and choreographers. Craig Johnson, author of the popular Sheriff Longmire mystery series, lives next door, and bases characters and locales on people and places he knows in the surrounding Powder River country.

Today, Sheridan County is primarily oriented toward tourism and agriculture, with the city of Sheridan serving as a regional center for banking, shopping and higher education, hosting Sheridan College. Outlying communities have their own identities, but good roads mean that everyone alike has access to urban conveniences and rural relaxation and scenery.

People like Sheridan County, from young families raising children to retirees drawn by the beauty of the Bighorns. Horses like Sheridan County too, just as they have for hundreds of years.

Resources

- Amundson, Michael. “The Mink and Manure Crowd: The History of an Elite Subculture in Wyoming.” Master’s thesis, University of Wyoming, 1990.

- Blair, Pat, Dana Prater, and the Sheridan County Museum. Images of America: Sheridan. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008, 90.

- Flying H Polo Club. “116 Years of Polo in Sheridan County.” Accessed Jan. 5, 2013 at http://www.flyingpolo.com/history.htm.

- Georgen, Cynde. In the Shadow of the Bighorns: A History of Early Sheridan and the Goose Creek Valley of Northern Wyoming. Sheridan, Wyo.: Sheridan County Historical Society, 2010.

- Hamalainen, Pekka. “The Rise and Fall of Plains Indian Horse Culture." Journal of American History Vol 90, No. 3, 3-21. Available as of Oct. 16, 2012 for pay-per-view access at http://jah.oxfordjournals.org/content/90/3.toc.

- Hininger, Scott. Sheridan County Extension Agriculture Educator. Telephone interview by author. Dec. 5, 2012.

- Irving, Washington. The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, U.S.A. 1837. Reprint, Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.

- King, James T. “General Crook at Camp Cloud Peak: ‘I Am at a Loss What to Do,’” Journal of the West 11 (Jan. 1972).

- Ringley, Tom. “Wranglin' Notes: A Chronicle of Eatons' Ranch 1879-2010.” Pronghorn Press, Greybull, WY (April 25, 2011).

- Sheridan County Extension Homemakers. Sheridan County Heritage Book. Sheridan, Wyo.: Sheridan County Extension Homemakers,1983.

- Wood, W. Raymond, and Thomas D. Thiessen. Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains: Canadian Traders among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738-1818: the Narratives of John Macdonell, David Thompson, Francois-Antoine Larocque, and Charles McKenzie. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma, 1985.

Illustrations

- The photo of the horse in the field above Story, Wyo. is by Andrew Tkach, from Panoramio. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the tie-flume trestle is from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks.

- The rest of the photos are all from the collections at the Sheridan County Museum. The photo of the polo players is from the Walsh collection; the photo of the queen is from the Mavrakis collection. All are used with thanks.

- In the photo of the miners, William Fred Wondra is kneeing in front at the right of center. The Avery model 8-16 tractor burned gasoline or kerosene. The polo players are currently unidentified.