- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Tongue River Tie Flume

The Tongue River Tie Flume

High in the Bighorn Mountains of northern Wyoming, flames crackled through the forest in the dry August heat of 1899. The fast-moving fire threatened the railroad tie-cutting camp at Rockwood at the head of the Tongue River Box Canyon. While the women and children fled, the men stayed behind to throw personal belongings into a nearby pond behind an earthen dam built as a holding place for the ties on the north fork of the Tongue.

About 25 women and children walked down the mountain on a footboard attached to a wooden flume, or waterway, built to float ties down the canyon to their final destination at Ranchester, Wyo., about 20 miles away. It was a hazardous journey: In some places, the flume hung 300 feet above the bottom of the canyon, and burning debris had fallen on the footboard, destroying a short section of it.

Miraculously, no one from the camp was hurt, though one man later died from pneumonia from standing in the pond to escape the fire. Most of the buildings, plus thousands of ties at the Rockwood camp burned, leaving only two cabins and a schoolhouse to J.H. McShane and Company, which had built the camp more than four years earlier, in spring 1895.

The first tie camp at Sheep Creek

The Rockwood camp was part of an operation begun in 1893 when the Burlington and Missouri Railroad was building its line from Sheridan, Wyo., north to Montana. By March 1893, two Omaha men, Dan Starbird and Thomas B. Hall, had contracted with the B & M to supply 1.6 million ties. However, the best trees for tie cutting grew high in the mountains, far from the railroad, and Starbird and Hall needed an efficient means of transport down the mountain. They decided to build a flume—a wooden trough many miles long, on trestles when necessary, sometimes anchored to granite cliffs with iron bolts, which would carry a volume of water at a steady grade and with it, the ties. Both the flume and the ties were made of pine, an abundant resource in the Bighorn Mountains.

The first workers' camp, for both tie cutters and flume builders, was located at the head of Sheep Creek Canyon, which drains into the Tongue River approximately 13 miles southwest of Ranchester, Wyo. The flume, constructed of 2-inch, tongue-and-groove boards to minimize leaking, was built in stages. When one section of the flume was finished, lumber for the next was floated down to the end. Then the water was shut off while the next section was built. The Sheep Creek flume, completed on Sept. 10, 1893, and emptying into the Tongue River, was four and one-third miles long.

Later that month, J.H. McShane and Company bought out Starbird and Hall. The company continued operations at the Sheep Creek camp, extending the flume from its lower end, where it had emptied into the Tongue, further northeast and downstream through the Tongue River Canyon about five more miles to where the river became more level. The company also improved the flume's design. The original flume was flat on the bottom, while the new design was V-shaped to keep the ties from dragging on the bottom. Three layers of 1-inch lumber replaced tongue-and-groove, and where the flume rounded a corner, the outside wall was built somewhat higher to better contain its floating cargo.

The Tongue River Box Canyon flume

By summer 1894, the supply of timber near Sheep Creek was thinning out, but demand for ties continued. Therefore, McShane and Company officials planned a new, five-to six-mile section of flume through the Tongue River Box Canyon on the main stem of the Tongue, to join up with the Sheep Creek flume near the junction of Sheep Creek and Tongue River where their earlier five-mile extension had begun. This would create a rough Y-shape, with the leg pointing east-northeast, following the Tongue toward Ranchester, and the new fork of the Y pointing west-southwest, into the Bighorn Mountains.

Construction through Sheep Creek Canyon was already an outstanding feat of engineering, manpower and horsepower, but Tongue River Box Canyon was much steeper and rougher. It was necessary to dynamite one area to remove enough rock to allow the flume to turn a corner, and this led to the only building-related casualties in the history of the flume. On Aug. 5, 1894, after the explosion, six men went to the site to inspect the results.

“[W]hen I … looked up to see where the boys were” eyewitness George W. Hall, who kept the men's time sheets, told The Sheridan Post, “I saw the rock above moving down toward them. I yelled, but all too late.”

Four of the six died: Three were buried under the falling rocks, and one was swept by a falling rock into the canyon, 400 feet below. A fifth man was badly injured, and the sixth escaped. This location became known as Dead Man's Point. Below Dead Man's Point, more blasting was necessary to create two tunnels through solid granite—one 70 feet long and the other 210 feet in length. In addition, where the flume ran high above the river, it was supported by iron pins driven into the walls of the canyon or by trestles, the highest of which was 96 feet.

Flume walkers, whose job it was to patrol the flume looking for log jams, broken flume boards or fallen trees, carried telephones so they could hook up to a line installed alongside the footboard and report the problem to the shipper in camp. If there were no obstacles, ties traveled the 11 miles from the head of the flume to its end in just nine minutes.

McShane and Company's move to Rockwood

In spring 1895, McShane and Company moved their camp to the head of the Tongue River Box Canyon, approximately two miles south of the Sheep Creek site. This settlement, Rockwood, grew to house 250 men plus their wives and children. With the continual demand for ties, McShane and Company expanded the Rockwood operation by extending the flume three miles west up to the foot of Murray Hill, near the junction of the north and south forks of the Tongue River. Ties cut on Murray Hill were skidded down the steep slope directly to the top of the flume extension.

By 1898, McShane and Company had expanded again about five miles south of Rockwood to Black Mountain. Crews had to haul ties on wagons or sleds down steep grades, and there were several accidents when loads fell on drivers, horses and mules. Though no people were killed, some animals were. To help avoid such problems, the company built a chute and flume extension on Mule Hill, the steepest part of the grade. With this extension plus the three-mile length to Murray Hill, the south fork of the Y now had a rough C-shape on its end, opening to the south.

Rockwood No. 2 and Woodrock

After the fire of 1899, McShane and Company established new headquarters at the north end of Black Mountain, naming this camp Rockwood No. 2. Through 1905, McShane and Company, which incorporated as the McShane Tie and Timber Company, rebuilt the burned sections of flume and resumed cutting and shipping ties, supplying 500,000 for the Burlington’s extension from Toluca, Mont., to Cody, Wyo.

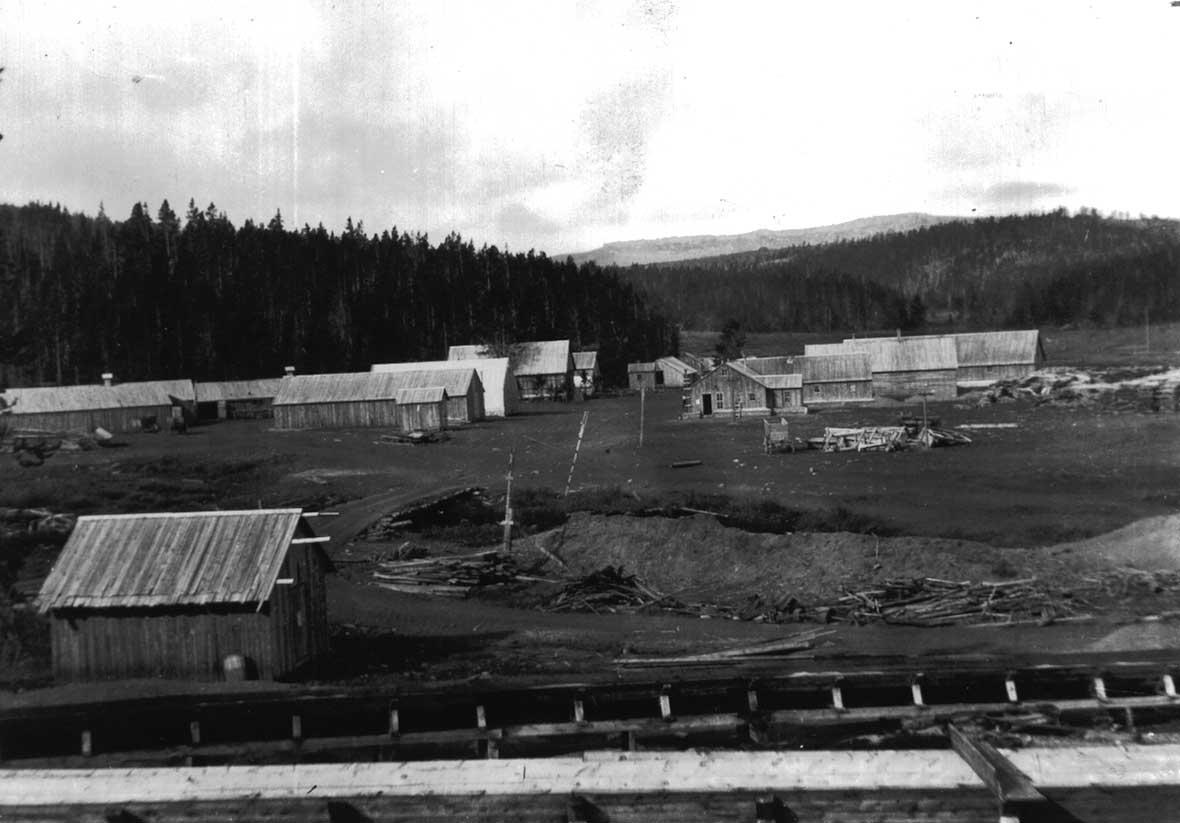

After searching for new areas of timber, McShane moved its headquarters again, in the winter of 1904-1905, this time to the south fork of the Tongue River, approximately 17 miles south of the original Rockwood camp, which had been abandoned after the fire. Named Woodrock, this settlement had a sawmill, cabins, bunkhouses, a cookhouse, barn and blacksmith's forge. In spring 1905, construction of 17 miles of additional flume was begun to join Woodrock to Rockwood No. 1. This section followed the south fork of the Tongue and continued one curve of the C-shape along the west end of Murray Hill and beyond in a long wiggly line, running south.

The Big Horn Timber Company

By early 1909, the Big Horn Timber Company had purchased the McShane Tie and Timber Company and taken over its operation at Woodrock. However, by 1913, lumber was being shipped to Sheridan by rail from Washington and Oregon, and the tie-cutting economy in the Bighorn Mountains came to an end.

Trees most suitable for ties were between eight and 11 inches in diameter, so probably all timber in that size range, in the above locations, was cut down. Additional lumber was used to build the flume and trestles, cabins and bunkhouses for workers, other buildings in the various camps and, as time went on, to supply lumber to the railroad for various uses other than ties.

The flume sometimes transported men as well as ties. On at least three occasions, workers from the camps, wanting a quick way down the mountain, built a flume boat and rode the flume to its end where it dumped them into the Tongue. Oscar Granum, a sawmill worker, built a V-shaped craft, closed at the back and open at the front. Boards nailed across made a seat for the rider, and although some water came in the front, it ran out the open spaces between the boards. There was no way to control the speed of a flume boat and, like the ties, it sometimes traveled nearly 75 miles per hour. Flume boat riders were supposed to get permission from the flume boss before taking the ride, and amazingly, nobody who rode a flume boat was ever killed or even seriously injured.

As of 2011, dilapidated sections of the flume and its supports still remained on Murray Hill, and near Needle Rock, approximately five miles northeast of Burgess Junction. A few other decaying remnants are scattered throughout the flume's original 38-mile length, the only traces of a structure that transported more than 2 million ties in the 20 years from 1893-1913.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “By Falling Rocks: Four Men Meet Instant Death at McShane's Tie Camp,” The Sheridan Post, Aug. 16, 1894, 5. Accessed Nov. 18, 2014, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- “From the Tie Camp,” The Sheridan Post, May 11, 1906, 1. Accessed Nov. 18, 2014, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Rawlings, C. C. “Tie Camp Was Sheridan's Major Industrial Project,” Sheridan Press, May 20, 1957, 2-5.

Secondary Sources

- Granum, Robert M., compiler. History of the “Tongue River Tie Flume”: Big Horn Mountains, Wyoming, 1893-1913. Sheridan County (Wyoming) Library Foundation, Inc., 1990, AX1-AX12.

- Laumann, Helen and Nathan Doerr. Twenty Years of Timbermen: The Story of the Tongue River Tie Flume. An Exhibit from the Sheridan County Museum, Sheridan, Wyoming. Exhibit Series, vol. 2. Sheridan, Wyo.: Sheridan County Historical Society Press, 2011, 1-6, 8-15, 20, 23-30, 37, 42.

Illustrations

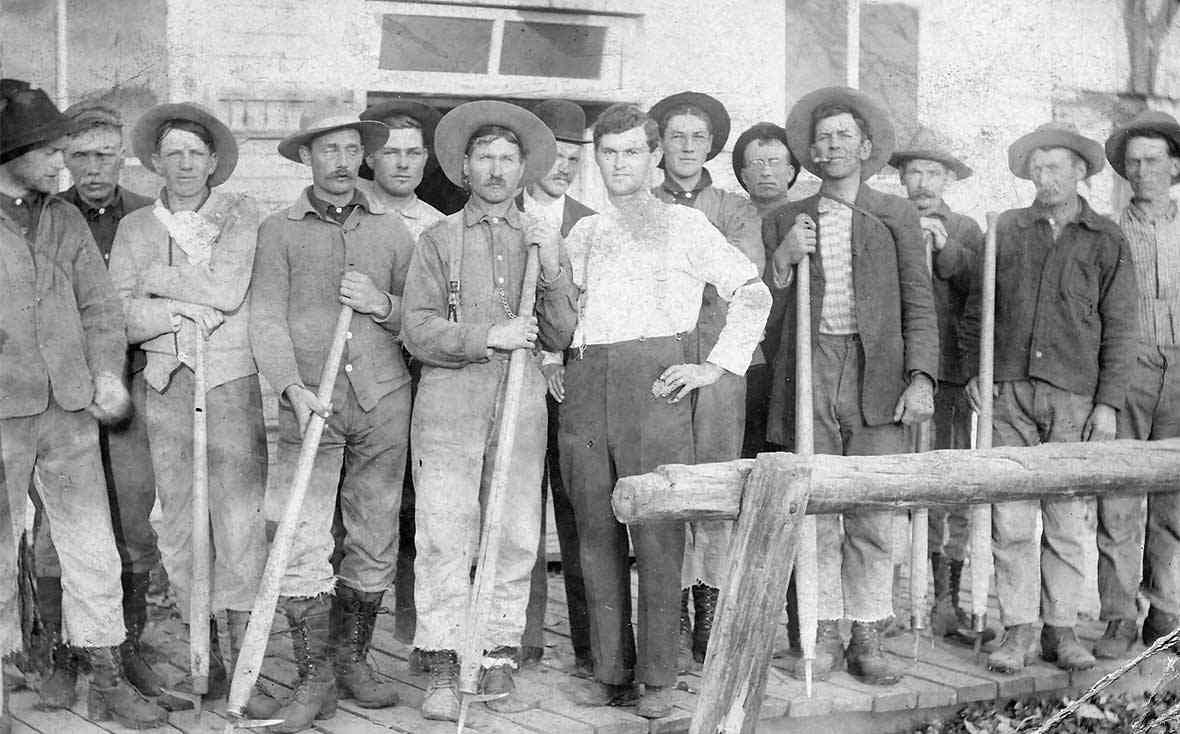

- All photos are from the collections of the Sheridan County Museum, used with permission and thanks. The photos of Woodrock and the the tie in the flume are from the Laumann Collection; the photo of the trestle is from the Ridley collection; and the photo of William Wondra and the tie hacks is from the Wondra Collection.