- Home

- Encyclopedia

- A Brief History of The Bozeman Trail

A Brief History of the Bozeman Trail

Gold Fever! The '49ers were among the first in the West to be infected with that contagion when they took the California Trail to the goldfields of the Sierra Nevada. Next were men like John Merin Bozeman who came to Colorado in the Pikes Peak gold rush, which began in 1859 and lasted throughout the early 1860s. Perhaps he even painted "Pikes Peak or Bust," on a wagon cover, as did many at that time.

Born in 1835 in Pickens County, Ga., Bozeman grew up at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains where placer mining was common. Believing that gold was the hope for a brighter future, his father left his home, wife and five children for the California goldfields in 1849. He took the route across the Isthmus of Panama, but died on May 14, 1852 aboard the Clarissa Andrews before reaching California. As it took 40 days to make the trip up the west coast, the body of 33-year-old William Bozeman was thrown overboard.

Perhaps influenced by his father's example, John Bozeman left his wife and three young daughters behind in 1860 to join a group of 15 men going to the goldfields in Colorado. The diggings there were less profitable than he had hoped, so he ventured on to the next hub of activity, heading north to Montana Territory. By then, some Pikes Peak veterans had discovered rich placer deposits along the banks of Grasshopper Creek near Bannack. Bozeman, however, did not arrive until June 1862 when that rush was nearly over.

In May 1863, a new deposit was found at Alder Gulch, about 75 miles east of the earlier strike at Bannack. Word spread fast and the miners left the Grasshopper Creek strike and rushed to the new diggings. Soon the hillsides along Alder Gulch were covered with miners’ tents, brush shelters and crude log cabins and when it came time to file the official document naming the new town, they called it Virginia City.

But Bozeman had changed careers. The steady stream of prospectors moving into the area led him to think that, instead of mining gold, he could make more money mining the miners. So, joining forces with local mountain man John Jacobs, he entered the guiding business. Bozeman was a promoter and Jacobs a seasoned guide who knew the lay of the land, the rivers, water holes and mountains. Together, they searched for a shortcut to the Montana goldfields from the Oregon Trail in what is now Wyoming.

An ancient route

The route they chose was a well-used corridor that Indian tribes had followed for centuries. By the 1860s it was also known to white explorers, trappers and traders. In 1859-1860, Capt. William F. Raynolds of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers led an expedition that explored the region in an effort to locate four possible wagon routes through northern Wyoming and southern Montana. Officials in the War Department hoped to build a network of roads that would open the area to white settlement. Raynolds’ guide was Jim Bridger, the former trapper, now guide and Army scout, who had lived in the Rockies for 40 years and understood well the topography of the West.

Raynolds reported that there was a belt of country 20 miles wide that was quite suitable for a wagon road, writing in part, “I doubt not it will become the great line of travel into the valley of the Three Forks [in Montana]. Being immediately at the base of the mountains, this strip is watered by the numerous streams, which rise in the hills, but soon disappear in the open country below, while the upheaval of the mountain crest is so uniform in direction that a comparatively straight road can be laid out close to their foot.”

The 500-mile-long corridor avoided both mountains and deserts and thus eliminated perhaps six weeks of travel time through rougher country. Good grass and water for the oxen or mules that pulled the wagons and fresh game and firewood for the travelers were available as well.

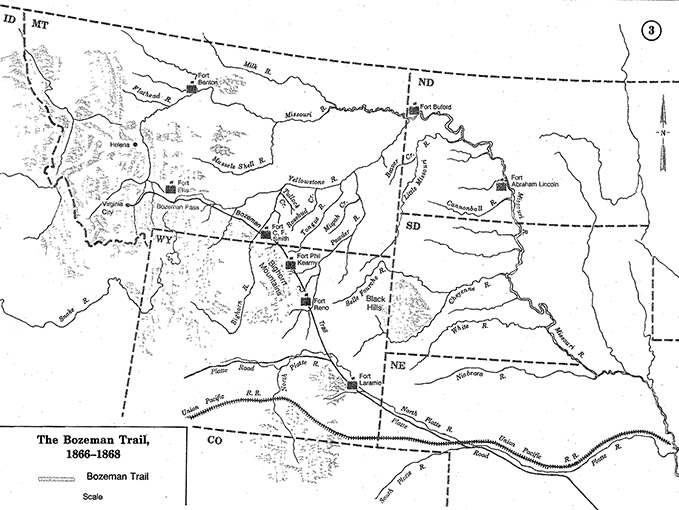

Image

Previously, gold seekers from the East either took steamboats to Fort Benton at the head of navigation on the Missouri River and traveled 250 miles southwest to Alder Gulch, or they took the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall in Idaho Territory, turned north, and traveled about 275 miles to the Montana gold diggings.

Bozeman’s route saved distance by traveling a diagonal, leaving the Oregon Trail at Deer Creek Crossing near present day Glenrock, Wyo. From there, they turned north through the Powder River Basin, which is bordered on the south by the North Platte, on the north by the Yellowstone River, on the west by the Bighorn Mountains and on the east by the Black Hills.

They then headed west toward the headwaters of the Tongue River, passing what are now the communities of Big Horn and Dayton, Wyo. From there they continued northwest, entering the Yellowstone Valley and progressing on through southern Montana to the goldfields at Virginia City.

A first attempt, 1863

The only drawback—and it proved to be a big one—was the danger from Indian attack. The trail crossed through prime buffalo-hunting grounds that had been promised to the Lakota Sioux under the terms of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Lakota, together with their allies the Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne, would violently resist this incursion onto their land.

The first of several emigrant trains began traveling up the trail not long after Bozeman and Jacobs had finished marking the route. A train of 46 wagons with 89 men, 10 women and several children left Deer Creek on July 6, 1863. Bozeman led the group, accompanied by Jacobs and another guide, Rafael Gallegos. They had traveled just 150 miles when they were confronted by a large party of Northern Cheyenne and Sioux warriors, who warned them to turn back or be killed. The disgruntled group retreated to the main emigrant road after learning that a military escort was unavailable to escort them safely to the goldfields. This incident occurred on Rock Creek, four miles north of present Buffalo, Wyo.

Bozeman and nine men forged ahead, however, risking their lives to follow the new thoroughfare. They rode through the nights and slept during the days, avoiding any further conflict with the Indians. After 21 days they safely reached the Gallatin Valley by way of what is now known as Bozeman Pass, between present Livingston and Bozeman, Mont. Bozeman’s bravery in pressing on to Virginia City through the shorter route earned him great deal of respect with the emigrants and was the main reason the trail was named for him.

The Townsend Train, 1864

A year later, four trains with a total of 450 wagons and 1,500 people traveled the Bozeman Cutoff to the Montana goldfields. This journey was basically without incident, except for the Townsend group.

The 150-wagon Townsend Train left Deer Creek late in June, according to historian Robert Murray. On the morning of July 9, they saw a large group of warriors approaching at a cottonwood grove on Soldier Creek, a short way west from the trail’s crossing of Powder River. Guides John Richard, Jr. and Mitch Boyer spoke with the Indians, and found they were on their way to raid the Crows. Captain Townsend gave the Indians food, but refused to let them travel along with the train.

When one of the emigrants turned up missing, Townsend sent a small force out to look for him. They found that the Indians had killed the man, and a fight followed. However, the emigrants had the upper hand as they were well armed with repeating Henry and Spencer rifles. Three emigrant men and thirteen Indians were killed in the battle, but the train then continued on to its destination without further incident.

Story’s Texas cattle

According to historian Susan Badger Doyle, the true emigration period of the Bozeman Trail lasted only from 1863-1866. Doyle observed that the emigrants didn't necessarily have the perception that the Indians would make their journey hazardous. She wrote that “the trail was yet another form of Manifest Destiny: they came out, they conquered, and they imposed their way of life. Most seemed to believe that the land was their due right and that the Indians would be overrun and would either disappear or be pushed aside.”

In 1866, Nelson Story, who had become wealthy prospecting in the Montana goldfields, sought a way to provide beef for the burgeoning mining camps. He bought cattle in Texas and despite the threat of Indian attacks, drove his herd of 3,000 head north on the Bozeman Trail. He was accompanied by a wagon train hauling groceries into the Gallatin Valley. Though the country was full of Indians, Story’s party moved forward unmolested.

However, trouble arose when they arrived at the construction site of Fort Phil Kearny near present Story, Wyo. Col. Henry B. Carrington was in command at the fort, one of the three forts being built that year to protect travelers on the trail.

Carrington demanded that Story’s party halt there because he could not guarantee their safety. One dark night Story and his cowboys rounded up his cattle and left. After only one minor skirmish with the hostile tribes, Story’s group reached Montana with all wagons and the herd intact.

Doyle also notes that by 1866, the trail became primarily a military transportation road. The tribes’ resistance to the presence of the forts and to military travel on the road became known as Red Cloud’s War, named for the Oglala Lakota Sioux war leader.

As for Bozeman, after only one season of guiding he retired from the business. He settled at the gate of the Gallatin Valley, founding Bozeman, Mont., in 1864. Three years later he was killed while traveling along the Bozeman Trail.

He and his business partner, Thomas Cover left Bozeman for Fort C.F. Smith on April 19, 1867 to see if they could land a government contract for flour from their flour mill in Bozeman. On the way an unexpected encounter with five Piegan Indians ended with Bozeman killed and Cover wounded. Cover made his way back to the town of Bozeman and reported his partner’s death. Some inconsistencies in Cover’s accounts, however, have led some historians to wonder if Cover himself might have killed his partner. Three years later, Bozeman’s body was relocated to Bozeman where it was buried in Sunset Hills Cemetery in Bozeman, Mont.

On Nov. 6, 1868, Red Cloud signed a treaty with the U.S. government that guaranteed the closure of the forts. After the Army departed, the Indians burned the forts, and the Bozeman Trail was officially closed. The route was used again in 1876, however, when troops under Gen. George Crook marched into the Powder River Basin three separate times on campaigns to subdue the Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux.

Today, the Bozeman Trail corridor is still a major north-south travel route, with an interstate highway replacing the wagon and horseback trails. Those who travel the trail can still see the grand, surrounding country and imagine how lush, pristine and full of promise the environment must have appeared to travelers who saw a new horizon on each day of their journey.

Ruts of the wagon road, located on public land near the Fetterman Monument in northern Wyoming can be viewed easily and provide contemporary evidence of the early day travel. There are also markers and historical interpretative signs at many other sites along the trail route.

Resources

- “Bozeman, John Marion.” Accessed Oct. 12, 2014, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=8611638.

- Doyle, Susan Badger. "Reflections,” in Promise: Bozeman's Trail to Destiny, edited by Serle Chapman and Susan Badger Doyle, 147-151. Park City, Utah: Pavey Western Publishing, 2004.

- Hebard, Grace Raymond and E. A. Brininstool, The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland Routes into the Northwest, and the Fights with Red Cloud's Warriors, vol. 1, 1922. Reprint, Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1960.

- "John M. Bozeman." Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com. Accessed Oct. 23, 2014 at http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/John_M_Bozeman.aspx#1-1G2:3404700836-full.

- Doyle, Susan Badger. Journeys to the Land of Gold. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press, 2000; See especially the brief bio of Bozeman, vol. 2, 741-742.

- McDermott, John D. Red Cloud’s War: The Bozeman Trail. Norman, Oklahoma: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2010, 307-308.

- Murray, Robert A. The Bozeman Trail: Highway to History. Fort Collins, Colo.: Old Army Press, 1999.

- Stanton, Edwin M., Secretary of War. Report of Brevet Brigadier General W. F. Raynolds on the Exploration of the Yellowstone and the Country Drained by That River. War Department, Washington City, July 19, 1867. Accessed Oct. 16, 2014 at https://archive.org/details/reportofsecretar1868unit.

- Stephen, Michael J. “The Bozeman Trail To Montana.” In Pioneer Trails West: Great Stories of the Western Americans and the Trails they Followed, edited by Donald J. Worcester. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1985, 212-223.

- Note: John Bozeman's middle name has been recorded as Merin, Merwin, Marion and Merlin. Primary source material found in a letter from his sister, Arminda Bozeman Leak to Mrs. J. E. Hart on May 10, 1905 shows Merin is the correct name. She lists the names of her brothers and sisters, with John M. Bozeman listed as John Merin Bozeman. Accessed Oct. 23, 2014 at www.oldthingsforgotten.com/familytree/sixdegrees/jmbozeman.htm.

Illustrations

- The map of the Bozeman Trail is from FortWiki. Used with thanks.

- The picture of John Bozeman is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The Edgar S. Paxson painting of Bozeman’s death is likewise from Wikipedia. Montana-based history painter Paxson, 1852-1919, was best known for his widely reproduced painting of Custer’s Last Stand, and for his murals at the Montana State Capitol in Helena. Used with thanks.