- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Miss Indian America Pageant In Sheridan, Wy...

The Miss Indian America Pageant in Sheridan, Wyoming

Lucy Yellowmule rode into history at the Sheridan WYO Rodeo on July 6, 1951. A young barrel racer from Wyola, Mont., she was a member of the Crow Nation, and a contestant for the title of WYO Rodeo queen.[1]

Normally the favored contenders were daughters of prominent Sheridan merchants or ranching families, but this year, two Crows—Yellowmule and 1950 Crow Fair rodeo queen Margo Real Bird—had entered the rodeo queen contest. Both Yellowmule and Real Bird made it to the semifinal selection round with Kathleen Grace Michelena, who was sponsored by the Arvada, Wyo., Woman’s Club.[2] In the end, Yellowmule’s horsemanship wowed the audience and earned their roar of approval.

When the story was told later, people suggested that boisterous rodeo cowboys tipped the scales in her favor by standing next to the applause meter used to select the queen. The cowboys loved the way she galloped her horse at full speed while decked out in her cowgirl hat and western clothes.[3]

The Crow Roping Club

Yellowmule had found her way into the spotlight using barrel racing skills developed through time spent at the Crow Roping Club. The embrace of rodeo sports was one way Crow people adapted cowboy culture to further Indigenous traditions of horsemanship that government officials and policies had been unsuccessful in suppressing since the start of the Reservation era.

The results of Yellowmule as rodeo queen

Lucy Yellowmule’s selection as rodeo queen had immediate and lasting effects on Sheridan’s relationship with its American Indian neighbors, and the effects rippled across Indian Country. Her selection as queen inspired the creation of All American Indian Days and the Miss Indian America Pageant, a self-billed “interracial project in human relations” that helped inspire future powwow pageants, and a quest for understanding and respect for American Indians that continues to this day.

In Sheridan, a town in the heart of the contested lands of the Great Sioux War of the 1870s, these efforts to seek justice and equality are still remembered and honored, inspiring action today and serving as a local counterpoint to Indigenous oppression in its many forms.

Sheridan: an anti-Indian town

Yellowmule was not the first American Indian rodeo queen in the West—Native American women had already earned that distinction at the Pendleton Roundup in Oregon in 1926, 1948 and 1951.[4] However, she was the first non-White woman to become rodeo queen in Sheridan, a town known for anti-Indian sentiment.

“Sheridan was the worst Indian-hating town in the country,” Dr. Joseph Medicine Crow recalled many years later. A decorated veteran and war chief who went on to become a Crow tribal historian, respected elder, honorary doctorate recipient, and Presidential Medal of Freedom winner, Joe Medicine Crow remembered getting off the train in Sheridan on his way home from World War II. The one restaurant where he felt sure of getting a hamburger with no hassle was the lunch counter run by Zarif Kahn, an Iranian immigrant with legendary hospitality known as “Hot Tamale Louie.”[5]

For the veteran Medicine Crow, who had just risked life and limb and acquired war honors fighting tyranny and Nazism, to know that his people were treated as lesser American citizens—right in their ancestral homeland—had a particular sting of injustice.[6]

For Indians visiting Sheridan, the anti-Indian sentiment didn’t change much between the immediate postwar years and the early 1950s. Many Main Street bars, restaurants and businesses were open about not desiring Indian trade. Crows from the Reservation would ride the train to town to conduct their business where they could, then wait under cottonwood shade in Kendrick Park until it was time for the next train home, all to avoid risking negative encounters on Main Street. A story circulating on the Crow Reservation at the time told of a fair-skinned Crow girl who tried to order hot dogs for her Crow friends at a Sheridan restaurant, only to be denied service because of her race.[7]

The seeds of such racist policies were likely in federal laws that prohibited the sale of liquor to American Indians until 1953—a restriction not imposed on people of any other race.[8] Regardless, during the poverty-stricken years of Prohibition and the Great Depression, Sheridan liquor flowed freely through back alley deals to Indians who couldn’t purchase alcohol on their “dry” reservations. Sheridan residents remember experiences with individual Indians who had too much to drink and no place to stay, so they slept in backyard gardens or along Goose Creek.[9]

The dysfunctional—and probably unconstitutional—laws prohibiting alcohol sale to Indians amounted to government-sanctioned racial profiling. With such laws in place, it wasn’t much of a leap for other business owners to broaden the idea, and exclude all Indians for whatever reason they chose. One notorious sign in a Sheridan business in the early 1950s read “No Indians or dogs allowed.” This is a Wyoming example of how laws that endorse unequal treatment of certain groups morph into widespread cultural prejudices and discrimination.

Sheridan was by no means alone as a reservation border town displaying these attitudes against Indigenous people. Lander, Wyo. had similar signs in the 1930s, as did placards in Greeley, Colo. that implied Mexicans were on the same level as canines.[10] Anti-Indian attitudes in Winner, S.D. in 1954 inspired filmmaker Tom Laughlin to create the popular anti-racist film Billy Jack, released in 1971.

In a nation that had just defeated Nazi oppression and genocide in World War II, certain individuals couldn’t ignore that America’s treatment of Indigenous inhabitants didn’t live up to the founding ideal of “all men are created equal.”

“Neckyoke Jones”

Luckily, when Lucy Yellowmule made her debut before the rodeo audience, a newspaper columnist and public relations expert, Howard Sinclair, was looking for ways to change things. Born in a ranching family near Glendive, Mont. in 1889, as a youth Sinclair became familiar with members of the neighboring Assiniboine and Yanktonai Sioux of the Fort Peck Reservation. When the Yanktonai Chief Grizzly Bear Standing’s grandson died in a horse accident, he made an honorary adoption of Sinclair in 1906 to staunch the grief.

These experiences gave Sinclair an affinity and sympathy for Indian people, and also knowledge of sign language and Dakota. He went on to a business education at Harvard, the study of law in Minnesota, and a career in New York publishing before moving back west to a ranch near Broadus, Mont. in 1939. Landing in Sheridan in 1941, he worked in public relations for cattle trade groups, and published a column called “Neckyoke Jones” in the Sheridan Press, which offered his takes on western issues in the voices of a salty old cowpuncher and his pal “Greasewood.”[11]

Just before the rodeo in 1951, Sinclair had penned a July 3rd Neckyoke Jones column describing how dismayed attendees at the Crow Sun Dance were that one of their young women was turned away from a Sheridan “eatin’ place” at the same time they were sending their young soldiers off to fight in the Korean War.[12]

So, when Lucy Yellowmule became queen of the rodeo, Sinclair saw an opportunity to open a discussion on the impact of anti-Indian sentiment on Sheridan’s Crow and Northern Cheyenne neighbors. He asked Yellowmule and her court to visit Sheridan and appear before various civic groups, veteran organizations and private homes to talk about their culture and the damage being done by racist signs in Sheridan. “It was emphasized that Indians have no more virtues nor no more vices than their White contemporaries,” Sinclair wrote in a classic statement of anti-racist rhetoric.[13]

Within a short time, the public relations campaign had shifted public sentiment to the point that restaurant owners voluntarily took down their anti-Indian signs. Though racism was by no means eliminated, at least public accommodations in Sheridan were nominally open to all. This basic act of fairness and equal treatment in commerce remains a pillar of anti-discrimination law and minority rights in the United States today, but back at the time Sheridan took these actions, the fight for such laws was more than a decade away. They ultimate passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act came after years of lunch counter protests in the South and the nonviolent marches of the Civil Rights Movement.

Sinclair deployed his public relations skills to make sure that Sheridan and Lucy Yellowmule earned recognition for these accomplishments, perhaps hoping that national media attention would cement egalitarian values as part of Sheridan’s culture.

A publicity trip orchestrated by Sinclair and his wife Ida culminated in Washington D.C on March 3rd, 1953 when Lucy Yellowmule accepted the Silver Anvil Award of the American Public Relations Association. Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay presented the award, and Yellowmule also recorded a segment for the Voice of America radio program.[14]

Also in 1953 the Freedoms Foundation in Valley Forge, Pa. awarded the Sheridan community a George Washington Medal for “outstanding achievement in preserving the American way of life by promoting better understanding between American Indian and White Races, and the elimination of racial discrimination.”[15] The award was presented during the Sheridan WYO Rodeo, by a representative from the Freedoms Foundation, a committee of Congressmen headed by Sheridan’s own Republican U.S. Rep. William Henry Harrison, and Felix Wormser, a representative from the Department of the Interior.

Lucy Yellowmule gave the following remarks in her acceptance speech:

Congressmens (sic), Harrison. again I feel honored to represent the Sheridan Community, on the behalf of this great honor from the Freedoms Foundation. I am proud to have had (sic) in this project to build a better understanding between the White and Indian Races. We all hope the goodwill which has been accomplished will last, and that we shall work together, and make America remain strong and great. Thank you.[16]

Miss Indian America Pageant and All American Indian Days

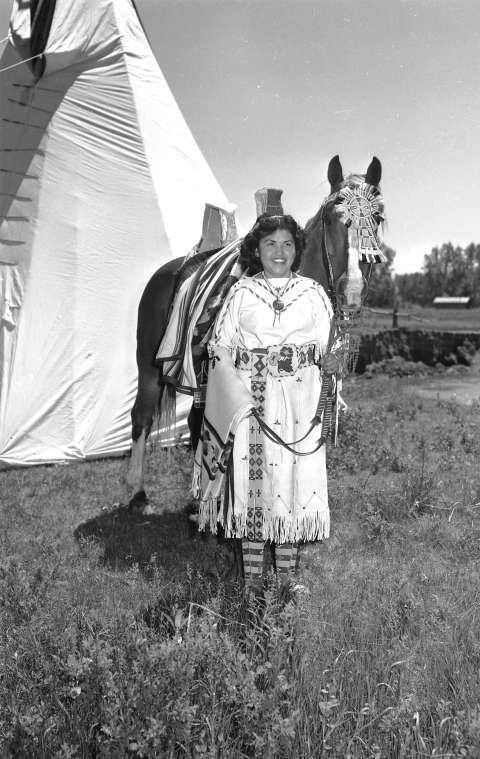

The idea for the Miss Indian America Pageant occurred to Sinclair when he and photographer Don Diers went to Wyola, Mont., to photograph Yellowmule. Seeking an image of Indian womanhood that he thought would have the most impact on the public, he asked Yellowmule to swap her cowgirl outfit for powwow regalia. As Sinclair described it, the sun came out and every bead on her traditional dress “sparkled like a diamond” as she stood smiling and proud, with her horse in front of a Crow lodge.

On the drive back to Sheridan, Sinclair and Diers reflected on the vision in buckskin of Yellowmule standing on the banks of the Little Bighorn River. This germinated into the idea of a pageant to honor young Indian women every year.[17] It would help further understanding, put the spotlight on Indian women and also, significantly, attract tourism to Sheridan that Sinclair hoped would be good for business.

In 1953, Sheridan held the first Indian Day and Miss Indian America contest at the Sheridan WYO Rodeo. Sinclair and a committee of organizers and Crow collaborators like Don and Agnes Deernose put out the call for contestants for the pageant. An estimated 3,100 Indians came from all across Indian Country to participate. Arlene Wesley, a Yakama who was the 1951 queen of the Pendleton Roundup, drove from Washington across Idaho and Montana to compete. She became the first-ever Miss Indian America at the night pageant held at the rodeo grounds.

In 1954 Joe Medicine Crow became an emcee for the event, joined by Brummet Echohawk, his Pawnee friend and fellow World War II veteran and Bacone Indian College student from Oklahoma.[18] The event was separated from the rodeo and christened All American Indian Days, a deliberate moniker that emphasized the citizenship and essential “Americanness” of Indians.

In the postwar era, such patriotic rhetoric was seen as a powerful tool for inclusivity by both Indians and non-Indians. Contrary to hierarchical racial mythology of White supremacy, the All American Indian Days embodied the idea that Indians could be fully American while also being true to their cultural traditions. The rhetoric was only strengthened when Sheridan was named an All-American City in 1958 for its work to combat discrimination.

By the middle 1950s, some thousands of Indians and about 100 candidates for Miss Indian America were coming to Sheridan to participate in All American Indian Days. The pageant judges during these years were White people with connections to Sheridan and Indian country, such as Father Peter Powell, author Walter Campbell (pen name Stanley Vestal), Emmie Mygatt, Elizabeth Lochrie, Herbert Brayer, and others.[19]

Local Sheridan organizers teamed up with an Indian Executive Committee to organize the event, tapping into the talent of Don Deernose, Joe Medicine Crow and prominent leaders across Indian Country. Members of the Rodeo Board and the local Kalif Shrine Masonic Temple formed various partnerships, including using All American Indian Days ticket sales to raise funds for the Shriners’ children’s hospitals.[20]

By 1958, the popularity of the event had not produced financial success, and partnerships disbanded as the pageant lost money. All American Indian Days recessed for that year. Sinclair himself felt he should be repaid funds he had put into to the project, and parted ways with the organization.[21] Resurrected in 1959, the pageant was held almost annually for another 30 years.

All American Indian Days involved a unique syncretic format that mixed and matched portrayals of authentic American Indian culture with a show designed for non-Indian audiences. However, unlike other pageants that invented scripted dramas for entertainment, Indian Days hewed closer to honoring and preserving authentic Indian culture, even if it sometimes romanticized pre-settlement life on the Great Plains.

The Miss Indian America Pageant, modeled after the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, N.J., was the keynote event that provided the dramatic tension for the other events. The pageant was supported by various demonstrations of American Indian culture and crafts, such as tepee setting contests, traditional horse races and ball games and art shows highlighting American Indian artists. The events included an award for Outstanding Indian of the year. A highlight for many was the magnanimous feeling of inter-racial connection cultivated at a Sunday inter-denominational church service led by an American Indian pastor, and often interpreted in Plains Indian sign language.

The result was a true mix of entertainment and efforts at educating and honoring American Indian culture and spirituality. Lakota veterans of the Great Sioux War would appear one year, while White tepee enthusiasts Gladys and Reginald Laubin might win the award for best-decorated lodge, besting actual Indian crafters.

Regardless of issues of representation and authenticity, for a few brief years as the pan-Indian cultural resurgence swept across America after World War II, Sheridan and All American Indian Days was an important place to be for residents of Indian Country. While Sheridan organizers were interested in entertainment and offering the public experiences with American Indians, substantive intertribal conversations were happening and relationships were being built beyond the fairgrounds spotlights, behind the scenes and sometimes out in the open.

In 1964, the National Congress of American Indians held its conference in Sheridan, and elected Vine Deloria Jr. as its president. In his 1969 book Custer Died for your Sins, Deloria singled out Sheridan’s own U.S. Rep. William Henry Harrison as a villain for supporting the Termination Policy that aimed to abolish reservation land bases and Treaty Rights.[22] Another year, Vine’s brother Sam first laid eyes on Vivian Arviso, the 1960 Miss Indian America whom he would later marry.

Natives take more control of the Pageant and All American Indian Days

As the 1970s dawned, so did American Indian thinking about the format of All American Indian Days. In particular, contestants for Miss Indian America started to question why an all-White panel of judges should select the titleholder.[23] This process had evolved out of the Sheridan board’s original idea that that White people could effectively select a Miss Indian America to be a well-spoken, attractive woman of Indian appearance, ancestry and attire, who could effectively represent American Indians and traditional knowledge to White audiences on national publicity tours.

Over the years, the title-holders had made numerous trips to other states, to overseas locations like Belgium and Paris and, in particular, paid visits to Washington D.C. to participate in inaugural parades, meet high-level administration officials, senators and even President Nixon. Some of the tours were chaperoned by Susie Yellowtail, the first Crow woman to become a registered nurse. On the other hand, Miss Indian America winners were required to stay in Sheridan in their off-time, where they lived with host families. These experiences ranged from negative and cloistered, to forming the basis for life-long friendships.

Within a few years after the 1968 Atlantic City Miss America Pageant saw protests about objectification of women, Miss Indian America winners started to demand a greater say in how they represented themselves, in particular in how they chose to dress.[24] Virginia Stroud, a Cherokee who was Miss Indian America in 1970-1971, noted that Plains-style attire — the buckskin powwow dress and eagle feather in a headband that was almost an unspoken requirement for competing for the title — did not actually represent her cultural traditions. She opted to wear a feather cape or contemporary clothes at her public appearances.[25] After a series of confrontations that played out on local radio and in the national press, the pageant changed the way women were selected, and added Indians to its judging panel.[26]

The powwow circuit and new pageants

The pageant continued to attract numerous contestants through the 1970s, but by the 1980s, large-scale participation in All American Indian Days had virtually ceased, as American Indians turned to the powwow circuit and other all-Indian gatherings to satisfy their cultural and social needs. Similar pageants took root, such as the first Miss Indian World Pageant at the Gathering of Nations in Albuquerque, N.M. in 1984, and the National Miss Indian USA Pageant in Washington D.C. in 1985.[27]

By 1984, Sheridan organizers and business supporters were fatigued by the annual effort, and the board decided to relocate the pageant to a new home. After several applications were made, the board licensed the Miss Indian America Pageant to the United Tribes International Powwow in Bismarck, N.D., where it was held until 1989.[28] At that point, the Sheridan members of the North American Indian Foundation that held rights to the pageant name were dissatisfied with how things went in Bismarck, so they recalled the license. However, organizers never regained momentum to hold the pageant again in Sheridan, or elsewhere.

Ongoing benefits

Even so, the Miss Indian America Pageant continues to resonate in Sheridan. The 1990s and 2000s brought a renewed focus on Sheridan’s long history of connection with its Crow and Northern Cheyenne neighbors, a story that included All American Indian Days, but had roots in rodeos and fairs dating back to the 1890s.

The resurgence in Indian participation in the Sheridan WYO Rodeo got a significant boost from the introduction of Indian Relay Racing as an event in the 1990s. This originally came about after Sheridan gallery owner Bill King introduced WYO Rodeo Board member Roger St. Clair to Shawn Real Bird, Crow rancher and horse racing promoter. Real Bird conceived of the World Championship Indian Relay races, which is now a key event at every Sheridan Wyo Rodeo. Others like artist Butch Jellis built relationships with prominent Crows like Truman Jefferson, resulting in some of the largest Crow participation in rodeo parades and festivities seen in generations.

In 2007, Sheridan Mayor Dave Kinskey and a delegation traveled to Crow Agency to meet with Crow Chairman Carl Venne and other representatives. As a result of this meeting, Sheridan Police Chief Mike Card teamed up with Tribal Police to help patrol the WYO Rodeo Street Dance, hoping to mitigate any tensions or interracial incidents that might arise among the party crowd. In 2013, Miss Indian America winners held a reunion in Sheridan, followed by another in 2015. In 2021, pageant winners organized an All American Indian Days Remembrance Event and raised funds for a memorial plaza to commemorate the interracial project in human relations.

In the midst of today’s movements for police reform and justice for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, the Miss Indian America Pageant is a notable example from the past of what can happen by elevating young women to positions of leadership. Many found their voice as Miss Indian America, and went on to be successful leaders in their chosen fields across America and throughout Indian Country, where they are still making a difference today. In a sense, the Miss Indian Americas paved the way for the many American Indian pageant winners that came after them.

For an event that ended decades ago, All American Indian Days and the Miss Indian America Pageant continues to inspire present generations with possibilities for reconciliation and achieving the American ideal of equality.

Such efforts work best when people use the cultural tools and formats available to them — such as rodeo, beauty pageants, powwow and parades — to meet as equals, build relationships and pursue common goals as Americans. The events have helped continue a tone for positive relationships between Sheridan residents and their American Indian neighbors, setting an example worth repeating by other western communities.

Resources

Primary sources

- American Indian Heritage Foundation press release, Sept. 11, 1985, Miss Indian America Collection, SCFPL

- Arviso, Vivian. “AAID Must Be More Involved with Indians,” Sheridan (WY) Press, Mar. 13, 1970.

- Billings Gazette, Aug. 14, 1984.

- Booth, Jack. National Miss Indian America Pageant board president, letter, ca. July 1983–Feb. 1984, Miss Indian America Collection, THE Wyoming Room, Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library (hereafter SCFPL).

- Hando, Mary Ella. Telephone interview with author, 2011.

- Minutes of National Miss Indian America board, Feb. 21 and Apr. 17, 1984, Miss Indian America Collection, THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL.

- Sheridan (Wyo.) Press, July 3, 19, 21, 1951; Oct. 14, 26, 1953; Aug. 3, 1955; Feb. 11, 1958; July 13, Aug. 3, 1968; June 9, 1983; Aug. 11, 1984. “Opinion—All American Indian Days Is in a Good Discussion,” Sheridan Press, n.d., copy in THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL.

- Medicine Crow, Joseph. Interview with the author, Lodge Grass, MT, July 2003.

- Medicine Crow, Joseph. Remarks during Miss Indian America Reunion, July 13, 2013.

- Medicine Crow, Joseph. Counting Coup: Becoming a Crow Chief on the Reservation and Beyond. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2006.

- Sinclair, Howard. "The Story Behind Sheridan's All American Indian Days," Wyoming: The Feature and Discussion Magazine of the Equality State 1, no. 5 (Aug.-Sept. 1957), p. 4.

- Sinclair, Howard. Interview by Robert Helvey, June 25, 1960, TS, Robert T. HelveyPapers,1902–1963, Mss 01465, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- St. Clair, Roger, personal communication with the author, June 28, 2021. Shawn Real Bird's father, the late Chuck Real Bird, was twin brother of Margo Real Bird, who had entered the 1951 contest for Sheridan WYO Rodeo queen along with Lucy Yellowmule. Shawn's mother Ramona Russel was also involved in Sheridan pageantry as a candidate for Miss Indian America.

- Stroud, Virginia. “Suggestions Given by Virginia Stroud—May, 1971,” n.d., All American Indian Days Collection, THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL.

Secondary sources

- Barkley, Evelyn. “Neckyoke Jones, Happy Warrior,” Denver Post, Aug. 1. 1954.

- Burbick, Joan. Rodeo Queens and the American Dream. New York: Public Affairs, 2002), 86.

- Deloria, Vine, Jr. Custer Died for Your Sins Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988, p. 62.

- Deutsch, Sarah. No Separate Refuge: Culture, Class, and Gender on an Anglo-Hispanic Frontier in the American Southwest, 1880–1940. New York : Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Gilbert, Hila. Making Two Worlds One; And the Story of All American Indian Days. Sheridan, Wyo. : Connections Press, c1986.

- Gilbert, Hila. “Making two worlds one.” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 21, 19, 1953.

- Gilbert, Hila. “All American Indian Days—The Beginning,” The Country Journal 4, no. 21, 1–12, copy in THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL

- Kendi, Ibram X. How to be an Antiracist. New York: Random House, pp. 17-23.

- Ringley, Tom. Rodeo Time in Sheridan, Wyo.: A History of the Sheridan- Wyo-Rodeo (Greybull, Wyo.: Pronghorn Press, 2004), 21, 216.

- Rosen, Ruth. The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America. New York: Viking, 2000, p. 159.

- Schultz, Kathryn. “Citizen Khan: Behind a Muslim Community in Northern Wyoming Lies One Man, and Countless Tamales.” New Yorker, June 6 and 13, 2016.

- Snell, Alma Hogan. Grandmother’s Grandchild: My Crow Indian Life Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Illustrations

- The 1950s photo of Miss Indian America contestants at a banquet in Sheridan was taken by Rochford Studios and is from the Elizabeth Lochrie collection at the archives of the Montana Historical Society. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of the 2014 national pageant winners in the powwow parade and the 2015 Miss Indian America reunion are both by Gregory Nickerson. The photo of the pageant winners first ran in WyoFile. Used with permission and thanks.

- The rest of the photos are from the collections at THE Wyoming Room, Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library. Used with permission and thanks.

For more on audio and video

- Click here to hear an audio recording of Lucy Yellowmuel's brief remarks at the Sheridan WYO Rodeo in 1953 when the Freedoms Foundation of Valley Forge, Pa. presented the community of Sheridan with a George Washington medal for promoting “better understanding between American Indian and white races.”

- View the author’s 15-minute documentary on the Miss Indian America pageant, produced in 2016, with interviews of many past pageant winners plus Joe Medicine Crow’s account of how the pageant began.

[1] Sheridan (WY) Press, July 21, 1951.

[2] Margo Real Bird was the 1950 Crow Fair rodeo queen, and was sponsored by the Crow Fair Rodeo committee. Real Bird’s brother Jim Real Bird was president of the Crow Roping Club, which had sponsored Lucy Yellowmule’s entry. “Crow Princesses Out For Queen,” Sheridan (WY) Press, July 21, 1951.

[3] Tom Ringley, Rodeo Time in Sheridan, Wyo.: A History of the Sheridan- Wyo-Rodeo (Greybull, WY, 2004), 21, 216.

[4] Joan Burbick, Rodeo Queens and the American Dream (New York, 2002), 86.

[5] Kathryn Schultz, Citizen Khan: Behind a Muslim Community in Northern Wyoming Lies One Man, and Countless Tamales, New Yorker, June 6 and 13, 2016.

[6] Joseph Medicine Crow, interview with the author, Lodge Grass, MT, July 2003; Joe Medicine Crow remarks during Miss Indian America Reunion, July 13, 2013; Joe Medicine Crow, Counting Coup: Becoming a Crow Chief on the Reservation and Beyond (Washington, DC, 2006).

[7] Alma Hogan Snell, Grandmother’s Grandchild: My Crow Indian Life (Lincoln, NE, 2001). Howard Sinclair remembered witnessing a similar situation in Billings, Montana when an American Indian veteran was denied service. Wyoming: The Feature and Discussion Magazine of the Equality State 1, no. 5 (Aug.-Sept. 1957), 4.

[8] In the Great Plains region, prohibitions against trading liquor to Indians dated back at least to the mid-1800s.

[9] Mary Ella Hando, phone interview with the author, 2011. In summer 2006, a visitor to the Sheridan County Museum told the author about selling his parents’ liquor to Indians when he was a boy.

[10] On the pervasiveness of such discrimination, see Sarah Deutsch, No Separate Refuge: Culture, Class, and Gender on an Anglo-Hispanic Frontier in the American Southwest, 1880–1940 (New York, 1989). A similar scene featuring discrimination in an ice cream shop was depicted in the 1971 independent film Billy Jack, inspired by the filmmakers’ experience of anti-Indian discrimination in Winner, South Dakota, in 1954.

[11] Sheridan (WY) Press, Aug. 3, 1955. Evelyn Barkley, “Neckyoke Jones, Happy Warrior,” Denver Post, Aug. 1. 1954. Sheridan (WY) Press, Feb. 11, 1958; ibid., July 13, 1968; ibid., Aug. 3, 1968.

[12] Sheridan (W) Press, July 3, 1951.

[13] Sheridan (WY) Press, Aug. 3, 1955; Hila Gilbert, Making Two Worlds One; And the Story of All-AmericanAll American Indian Days (Sheridan, WY, 1986), 9.

[14] Gilbert, Making Two Worlds One, 9; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 21, 19, 1953.

[15] Sheridan (WY) Press, Aug. 3, 1955.

[16] An audio recording of the Freedoms Foundation presentation is available in THE Wyoming Room at the Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library, entitled: “Byron – Freedom Foundation-Lucy Yellowmule.” At this event, the official representative of the Department of the Interior, Felix Wormser, congratulated Sheridan and the Crow and Cheyenne nations for efforts to put all people on equal footing regardless of skin color. He then segued into promoting Eisenhower-era Indian policy, which argued in political euphemisms for a “smaller” role of the federal government in Indian relations so that Tribes could entirely “manage their own affairs.” Rep. Harrison and the Congressional committee were in town precisely to discuss such ideas, which advanced the soon-to-be notorious 1950s Termination policy, an attempt to extinguish the federal government’s trust responsibilities and the land bases of Indian tribes, which were guaranteed by treaties. Ultimately, most of Indian Country rejected and defeated this federal policy, with the help of some of the Native luminaries like Vine Deloria Jr. who later attended All American Indian Days. Likewise, the Miss Indian America pageant did not equate being on “equal footing” in public accommodations with a desire for assimilation into mainstream society. Instead, the pageant became a platform for increasing assertiveness and cultural self-determination among Miss Indian America pageant candidates, especially when it came to their personal appearance and the organization and judging of the pageant.

[17] Hila Gilbert, “All American Indian Days—The Beginning,” The Country Journal 4, no. 21, 1–12, copy in THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL.

[18] Gilbert, Making Two Worlds One, 21.

[19] Many of these judges collected Miss Indian America memorabilia and correspondence, which they donated to archives in Sheridan, the Montana Historical Society, Stanford University, and elsewhere.

[20] Sheridan (WY) Press, Oct. 26, 14, 1953; ibid., July 19, 1951.

[21] Howard Sinclair, interview by Robert Helvey, June 25, 1960, TS, Robert T. HelveyPapers,1902–1963, Mss 01465, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY. It’s not clear from the archival record what Howard Sinclair’s beliefs were about Termination policy, but photographs suggest he had a relationship with Termination advocate Rep. Wm Henry Harrison. It’s possible that Sinclair’s views of Termination were crosswise with Indian attendees of Indian days.

[22] Vine Deloria Jr., Custer Died for Your Sins (Norman, OK, 1988), 62.

[23] Arviso, “AAID Must Be More Involved with Indians,” Sheridan (WY) Press, Mar. 13, 1970.

[24] Ruth Rosen, The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America (New York, 2000), 159.

[25] Virginia Stroud, “Suggestions Given by Virginia Stroud—May, 1971,” n.d., All American Indian Days Collection, THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL.

[26] “Opinion—All American Indian Days Is in a Good Discussion,” Sheridan (WY) Press, n.d., copy in THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL;

[27] American Indian Heritage Foundation press release, Sept. 11, 1985, Miss Indian America Collection, SCFPL.

[28] Sheridan (WY) Press, June 9, 1983; Jack Booth, National Miss Indian America Pageant board president, letter, c. July 1983–Feb. 1984, Miss Indian America Col- lection, THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL. Minutes of National Miss Indian America board, Feb. 21 and Apr. 17, 1984, Miss Indian America Collection, THE Wyoming Room, SCFPL; Billings Gazette, Aug. 14, 1984; Sheridan (WY) Press, Aug. 11, 1984