- Home

- Encyclopedia

- “Let Us Ramble:” Exploring The Black and Yellow...

“Let Us Ramble:” Exploring the Black and Yellow Trail in Wyoming

Come brother, let us ramble

O’er the Black and Yellow Trail.

O’er the Black Hills let us scramble

Into canyons deep and vale.

They put the black before yellow

When they named this glorious route,

Because the Black Hills greet you first

And then yellow stone salute.

Ah, ‘tis indeed a trail of beauty

Where Dakotas used to roam

Where the bear and mountain lion,

And the deer are still at home….

…Health, wealth and adventure you’re seeking you say

In Wyoming you may

Pick up all three most any day

(Excerpt from “The Black and Yellow Trail,” by Mrs. C.L. Benson (News Journal, Gillette, Wyoming., Nov. 18, 1920)

Places to go, no way to get there

In the 1910s, Model T cars were rolling off the assembly line by the thousands. Henry Ford’s goal was to put an affordable car in every garage, and Americans who had so far been tethered to railway tracks were prepared to explore their country. Yellowstone had been a national park since 1872, but such attractions were available only by passenger train. Now Americans were ready to hit the road, but upon venturing out of town they found only a haphazard patchwork of poorly maintained county roads.

The need for a reliable road system was recognized by “men of vision,” who also foresaw the potential of auto tourism, and groups across the country began a movement to develop “good roads.” As early as 1912, local booster clubs were organized to attract business to small towns. Tourists would require decent roads, service stations for gas, cafes, groceries and safe places to spend the night. Boosters were eager to place their small towns on the route of the newly planned highways.

The vision

One of the earliest interstate roads was envisioned to enable auto tourists to drive from Chicago to Yellowstone National Park via the Black Hills. In February 1912, delegates from more than 40 towns in South Dakota and Wyoming met in Deadwood, S.D., and formed the Chicago, Black Hills and Yellowstone Park Highway Association to develop a highway of the same name. It was soon known as the “Black and Yellow Trail.” The name included not only the major attractions of the Black Hills and Yellowstone National Park, it also described the black- and yellow-banded posts that would mark the route. The association planned an extensive publicity campaign to raise interest and funding.

A “good roads” convention was held in Buffalo, Wyo. in June 1912 to decide the route of the highway through Wyoming. Delegates lobbied to have their hometowns included and eventually laid out a route that would pass through Beulah near the South Dakota-Wyoming state line, then continue west to Sundance, Moorcroft, Gillette, Buffalo, Ten Sleep, Worland, Basin, Greybull and Cody, and finally arrive at the East Entrance of Yellowstone National Park—“a Wonderland all the way.” Travelers follow a similar route today when they drive I-90 from Beulah to Gillette, U.S. 14-16 from Gillette to Ucross, and U.S. 16 on through Buffalo, over the Bighorn Mountains and through the Bighorn Basin to Yellowstone Park.

The Black and Yellow Trail, like many early highway routes, tended to parallel existing railroad lines wherever possible. Railroads usually represented the shortest distances between towns, and roads laid out along tracks required less disturbance of valuable farm-ranch land and had fewer problems in obtaining access for right-of-way. Making this route a reality would require a combination of improving existing county roads—varying widely in quality—and raising funds for new construction.

Many delegates at the 1912 state convention in Buffalo were skeptical that an auto road could successfully cross the Bighorns. To prove that it could be done, one of the delegates, Basin businessman Anson Higby traveled to the convention across the range in an old Studebaker. Higby and others who ventured over the mountains followed a system of established logging and mining roads and old mail routes. Within a few years (1915-1917), the first official construction would begin on the challenging route across the Bighorns.

The route

In the spring of 1913, the Chicago, Black Hills and Yellowstone Park Highway Association held a second annual convention in Deadwood, S.D. Delegates from interested towns along the route decided to map and mark the Black and Yellow Trail with black and yellow striped posts at all key points. The convention was followed that summer by a “Pathfinder and Booster Tour” organized by the Association, with Ben W. Wood as chairman. His party traveled the proposed route and held booster meetings along the way to stir up local enthusiasm. Chairman Wood issued a bulletin and described the Wyoming portion:

In Wyoming the highway was traveled through the counties of Crook, Campbell and Johnson, via the cities of Sundance, Moorcroft, Gillette, Sussex to Buffalo. This road is a prairie road. It goes through a most interesting country. Evidences of considerable improvements were found along the line. In Crook County the road was undergoing a change in many places to avoid steep grades, etc. New culverts and bridges were being installed…. From Cody to the east entrance of the park, the destination of the Pathfinder Tour, the road traverses through the famous Shoshone river canyon. It is beyond our ability to describe this picturesque stretch of the road. It is a government highway and upon it the government of the United States has spent thousands of dollars. It will measure up with the best highway in the country.

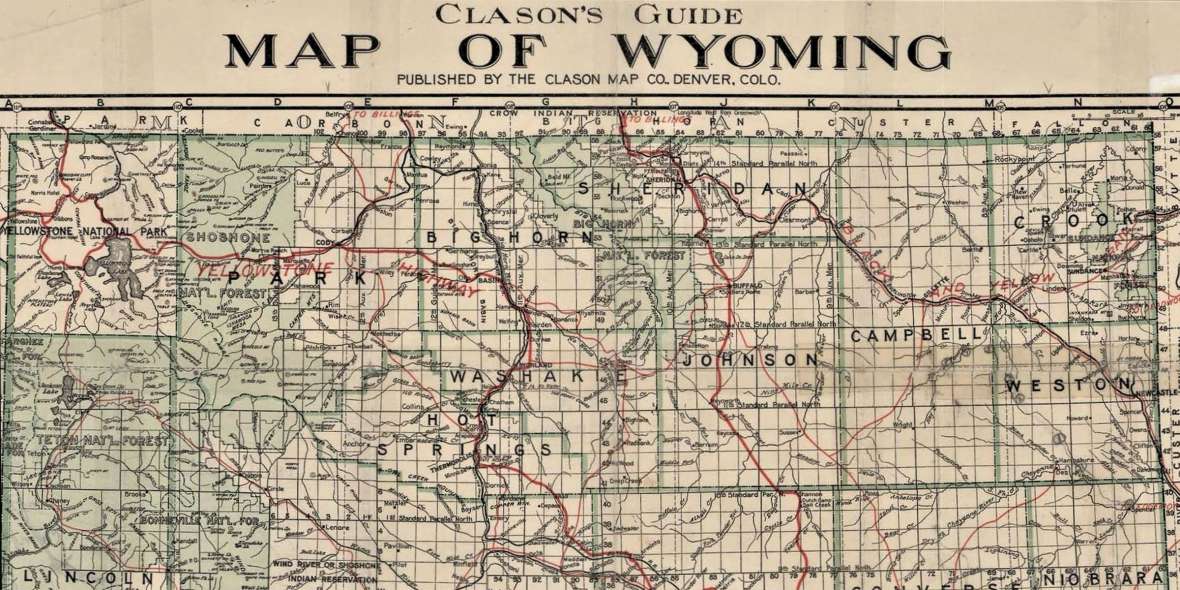

The portion of the existing road between Gillette and Buffalo originally detoured far to the south to pass through Sussex, east of Kaycee, Wyo., a 135-mile trip. A proposed realignment due west from Gillette shortened the trip by 50 miles. Clason’s Guide, Map of Wyoming (1916) depicted the route of the trail generally following the right-of-way of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad from Moorcroft west to Arvada, a more direct route than the old road through Sussex. However, the 1920 survey by the State Highway Department suggested a route that would pass through Spotted Horse to the north—the route of today’s U.S. 14-16. Thus, for several years the Black and Yellow Trail was an evolving route.

Meanwhile, the number of auto tourists was growing rapidly. Early motorists tended to be “a relatively homogeneous community of upper-and-middle class, urban, white Americans” who would occasionally meet up with traveling salesmen, migrant workers and tramps. Auto trips demanded planning, time and money. Local businesses started offering auto camps, often supplying tents, beds and camp chairs. These evolved into tourist camps that provided small cabins, groceries or a café, and laundry facilities (picture Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night). Later, migrant workers could stay in safe, clean government camps, like Steinbeck’s Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath.

Federal aid to the rescue

From about 1912 to 1917, most construction was financed by individual counties (or in the case of the Bighorn Mountains, the U.S. Forest Service). Piecemeal progress depended on local fundraising. Wyoming was home to three of the early interstate highways—the east-west Lincoln Highway, the south-north Yellowstone/National Park-to-Park Highway from Denver to Yellowstone and, in the northern part of the state, the Black and Yellow Trail. Although local booster clubs envisioned the routes and started construction, the time was ripe for state and federal governments to help.

In 1917, the Wyoming state legislature created the Wyoming Highway Department. It was administered by a state highway commission; a key proviso authorized the acceptance of federal aid on a matching basis under the Federal Aid Act of 1916. The matching funds were raised through a bond issue of $2.8 million approved by the voters in 1919 and a second issue in 1921. Qualifying for federal aid were the Lincoln Highway, the Yellowstone Highway and the Black and Yellow Trail.

Improving on efforts underway earlier in the 1910s, portions of the trail were divided into several “FAPs” (Federal Aid Projects). Various segments of the highway were often surveyed and under construction simultaneously. FAPs were assigned a variety of project numbers, some of which changed over time, resulting in a complex series of contracts. (The reader interested in specific FAPs is referred to the Biennial Reports of the State Highway Commission of the State of Wyoming, available at the Wyoming State Library.)

Fine-tuning the route

In the eastern portion of the state, the trail originally ran from Spearfish, S.D., passed through Sundance, Wyo. then trended southwest to Moorcroft. This route included today’s State Route 113 along the south side of Keyhole State Park, clearly marked as the “Black and Yellow Trail” on the Moorcroft U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangle, surveyed in 1914 and 1915 and issued in 1918. However, with the creation of the Wyoming Highway Department and the designation of the Black and Yellow Trail as a Federal Aid Project, the route was changed to swing through Carlile, Wyo. to the north, then head southwest to Moorcroft. The new route, though more indirect, was wisely located near Devils Tower, a tourist bonus. The original route of the trail along today’s State Route 113 was eliminated from the state highway program, and the route through Carlile became official.

This stretch was designated the Custer Battlefield Highway, and the FAP included about 10 miles of road construction northeast from Moorcroft toward Carlile. In 1919, the Custer Battlefield Highway Association was organized by W.D. Fisher, the secretary of the Sheridan Chamber of Commerce and a “good roads” advocate. This group promoted a more northerly route across South Dakota, entering Wyoming just west of Sturgis, S.D. It was to follow the general route of today’s U.S. 14-16 to Sheridan, and then north into Montana to the Custer Battlefield. The probable motivation for this road was the earlier decision for the Black and Yellow Trail to bypass Sheridan in favor of Buffalo. As a result, the Black and Yellow Trail and the Custer Battlefield Highway shared the same route in this area.

By the late 1910s and early 1920s, the Federal Aid Projects were carried out using uniform specifications. Generally, roadways were constructed 24 feet wide with corrugated metal pipe culverts and reinforced concrete culverts. For the Custer Battlefield Highway, grading began in July 1920, and the entire project was finished in April 1922, with gravel surfacing on five miles. Due to the shortage of steel at the time, the bridge design for the Belle Fourche River crossing was changed from steel to a 100-foot reinforced concrete structure at a cost of $29,000.

The remaining 16 miles of highway between the end of the above project and Carlile were completed under Federal Aid Projects in two phases that included grading, culverts and shale surfacing (completed in 1921), plus grading and construction of a roadway 24 feet wide covered with an 18-foot wide shale surface with culverts and bridges (completed in 1923). The segment from Moorcroft to Carlile was originally designated as Route 12.

Gillette to Buffalo

In 1919-1920, a survey was completed of the projected route between Gillette and Buffalo via Spotted Horse, Clearmont and Ucross. “This covers investigation and survey of 47 miles of an entirely new road from Gillette via Recluse to Arvada and the platting of complete plans for nine miles.” This new route deviated from the former proposed route of the Black and Yellow Trail that paralleled the right-of-way of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad between Gillette and Arvada. It was longer, and it is unknown why this more circuitous route to the northeast through Spotted Horse was chosen by the surveyors. Funds were also allocated for the construction of a nine-mile segment in the vicinity of Spotted Horse Creek between Gillette and Arvada, “being the heaviest construction on the 47 miles between Gillette and Arvada. The structure across Spotted Horse Creek is a reinforced concrete bridge 100 feet long.” The plans specified a 24-foot road surfaced 16 feet wide with “selected material” surfacing.

Under another Federal Aid Project, state work forces were employed on a 29-mile segment north of Gillette. According to the 1919-1920 Biennial Report, “About 25 miles have been built on a newly located line complete, but the old road and old bridge are used to cross Rawhide and Wild Cat Creeks”:

The grades on our new location are reduced to 7% and distance is shortened two miles. The new roadbed is twenty-four feet wide and was built for the most part with State tractor outfit and blade graders. The necessary corrugated iron culverts were installed with rubble masonry endwalls, and six timber cattle passes were built. Work was started in July, 1920, and is primarily a connection between Gillette and Project C1-6 [vicinity of Spotted Horse].

Another difficult section was between the Sheridan County line and Spotted Horse, about 10 miles, and demanded cutting down heavy grades and placing corrugated iron culverts. By the end of 1922, the section required additional appropriations estimated at over $10,000.

The entire 47-mile segment of highway was described in the Biennial Report for 1922-1924:

We find but one route in this county (Campbell) which, however, bears two numbers, viz: numbers 12 and 13, No. 12 indicating the route through the State known as the Custer Battlefield Highway, and No. 13 indicating the route known as the Black and Yellow Trail. These two highways coincide from Moorcroft in Crook County to Ucross in Sheridan County. Although this route has been improved throughout the whole county as a tractor graded road, the necessity is constantly arising of raising the fills through the low places to eliminate snow hazards, the installation of additional corrugated iron pipe culverts and the construction of gravel surface where the local material is bad.

The next Biennial Report (1924-1926) indicated that two Federal Aid Projects spent a considerable amount of money grading, surfacing and draining the new road from Gillette to Arvada. The first project required $75,246 and the second required $67,557. From 1926 to 1928, an additional $57,720 was spent on grading and draining.

Crossing the Bighorns

The most challenging segment was the crossing of the Bighorn Mountains between Buffalo and Ten Sleep. In 1915, before the era of Federal Aid Projects, August Hettinger of the Buffalo District of the Bighorn National Forest met with local officials to offer an allocation of $15,000 to construct a portion of the road within the forest boundaries. Work began that summer on a two-mile stretch of an existing county road in Mosier Gulch west of Buffalo and was completed by October. Given the difficult nature of the route, engineers speculated that it might be possible to construct 20 miles of road the following year.

In 1917, a $10,000 survey was completed for the forest road from Buffalo to Ten Sleep. The portion that was located in the forest qualified under the Section 8 Fund of the Federal Aid Act, which provided federal funding for forest roads. In 1918, $20,000 was spent on building five miles of this 75-mile roadway.

Construction was divided into two sections: the 22-mile Buffalo-Sourdough Section, which was the approach up Clear Creek from Buffalo, and the 53-mile Sourdough-Ten Sleep Section. In May 1919, a Cooperative Agreement between the State of Wyoming and the Secretary of Agriculture enabled the Buffalo-Sourdough Section to be built by the Forest Service at an estimated cost of $105,000. (The Forest Service is part of the Department of Agriculture.)Wyoming’s share was $25,000. The next section west, Sourdough to Ten Sleep, would be built by the Forest Service at an estimated cost of $210,000, of which the state would pay $85,000.

Wyoming divided its cost among the three counties involved: Johnson, Big Horn and Washakie. By 1920, 90 percent of the Black and Yellow Trail had been completed in the Johnson County portion, but only 35 percent had been completed in Big Horn County. (The county line runs along the mountain crest.) It appears, then, that the road was generally built from east to west. The entire Buffalo-Ten Sleep Road was finally completed by September 1922—a graded gravel road without an oiled surface, constructed with a combination of horse-drawn equipment, Caterpillar trucks, graders and dump trucks.

The final destination

Auto tourists who crossed the Bighorns via the Black and Yellow Trail proceeded west from Ten Sleep to Worland, where they joined the Yellowstone Highway. This road was conceived at about the same time as the trail. A “good roads” club convention was held in Douglas to promote a north-south route to Yellowstone National Park from Denver, Colo., and delegates from Buffalo were sent to encourage a linkup of the two highways. The Yellowstone Highway (today’s U.S. Route 20) passed through Douglas, Wyo., Casper, Shoshoni, the Wind River Canyon (after 1924), Thermopolis and Worland (where it joined the Black and Yellow Trail), then north through Basin, Greybull and Cody, and on to Yellowstone. The two routes, therefore, were the same from Worland to the East Entrance of Yellowstone National Park.

Yellowstone was subject to early legislation prohibiting steam vehicles within park boundaries; this was meant to bar steam trains but was later interpreted to include all power vehicles including cars. Some Yellowstone personnel felt that autos would ruin the park. However, the numerous “good roads” clubs were determined that auto tourists have access to Yellowstone, and they had a strong influence on park policy. Also, officials realized that allowing access to cars would greatly increase visitation. Auto tourism in Yellowstone was inevitable, and the park welcomed the first cars at the East Entrance in 1915. This policy led to improved roads, both within Yellowstone and leading to the park, such as the Black and Yellow Trail and the Yellowstone Highway.

But this “devil’s agreement” would haunt some Yellowstone officials far into the future. Almost two decades after the first cars passed through the East Entrance, Sanford Hill, landscape architect for the New Deal’s Emergency Conservation Work (ECW), lamented in his 1934 report:

In the early days of the Park the stage coach and pack outfits were the means of transportation. The stories told by these early adventurers are indeed very interesting, and it seems that the pleasures and thrills they enjoyed were lasting memories in their lives. They were fortunate, however, in seeing the Park in its natural state…The progress of man has changed this picture until now people rush through the Park seeing only a few of the many wonders…High speed highways and automobiles have no place in the picture painted by Mother Nature…the writer strongly recommends the return of the stagecoach and pack outfits…

Today, with yearly visitation exceeding three million, one can foresee a future when the park could prohibit private auto travel, granting Sanford Hill’s wish.

Marking the roads

The Black Hills and Yellowstone Park Highway Association set May 16, 1921, as the day for the Boy Scouts, the Good Roads Club and other civic groups to erect signs along the Black and Yellow Trail. In July, a group of two hundred Boy Scouts from Clinton, Iowa, traveled the route in 60 automobiles, passing through Buffalo and over the Bighorn Range en route to Yellowstone National Park.

In 1925, the federal government recognized the need for a national system of highway marking. The new system designated east-west routes with even numbers and north-south routes with odd numbers. The standard U.S. route marker became a shield bearing the number of the route, the letters “US,” and the name of the state in black on a white background. The Black and Yellow Trail was designated U.S. Route 16.

Paving the Black and Yellow Trail

During the mid-1920s, the Wyoming Highway Department made a concerted effort to “oil” the major roadways with gravel and crushed rock surfaces. Early efforts proved unsatisfactory as the surface disintegrated within a few months, creating a very rough roadway. Starting in 1927, a new oil formula proved more durable. Known as the asphaltic oil treatment or more commonly known as “blacktop,” it was soon in use on roadways across the state.

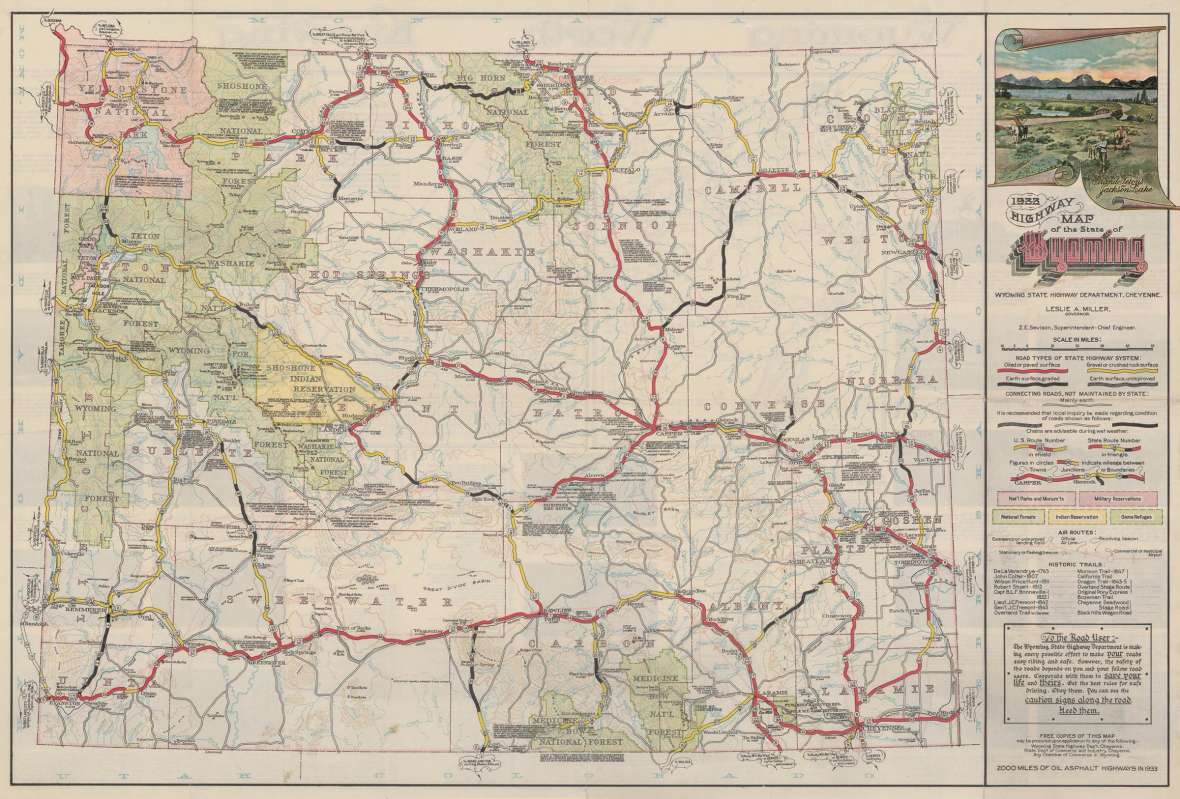

By the end of 1926, the highway department had improved the trail from the Wyoming-South Dakota border westward to its connection with the Yellowstone Highway in Worland. However, the highway consisted of segments of varying conditions, ranging from unimproved to surfaced or paved highway. In 1930, the trail from Buffalo over the Bighorn Mountains to Ten Sleep was described as an “all-weather” road that was not paved or oiled. In 1931, $128,000 became available to regrade and oil 11 miles of the road from the North Fork of Clear Creek to the crossing of Sourdough Creek. The 1932 Highway Map of the State of Wyoming depicted U.S. Route 16 as a gravel or crushed rock surface from Gillette to the Sheridan County line.

Federal Aid Projects reconstructed the road between Ten Sleep and Worland in 1936. As a result of this upgrade, portions of the original roadway were relocated, and a new truss bridge (still in place today) was constructed over the Nowood River just west of Ten Sleep. In the 1960s, U.S. Route 16 was reconstructed between Ten Sleep and Worland, generally north of the 1930s highway. The trail became a county road (580A) and included the truss bridge over the Nowood River.

In the mid-1930s, two highway projects began applying asphaltic oil treatment to the trail between Buffalo and Ten Sleep. A 2-1/2” oil mat was laid over a 3-1/2” gravel base, completed by September 1940. This work also involved grading and overall improvement of the roadway surface. From 1939 to 1941, the trail from Gillette to Arvada was improved in a similar manner. Other improvements involved grading, widening, overall upgrading of the roadway surface, new concrete bridges and some major realignments of the right of way.

The portion of the Black and Yellow Trail over the Bighorns did not receive any further improvements until after World War II. In the early 1940s the road had suffered from neglect due to the war effort. However, in 1946, the first five miles of the roadway up Mosier Gulch was reconstructed with reduced grades, gentler curves and a wider road surface. By the end of the summer of 1946, a heavy asphalt mat was laid on the new road.

Finally, the construction of Interstate 90 in the 1960s fundamentally changed traffic patterns between the Wyoming-South Dakota state line west to Buffalo. It provided a more direct link between Gillette and Buffalo, and The Black and Yellow Trail (U.S. Route 14-16) through Spotted Horse, Arvada, Clearmont and Ucross became a secondary route. The northward curving section of the trail between Sundance, Carlile and Moorcroft suffered the same fate, although a portion of it is used today to access Devils Tower National Monument. Today’s U.S. Routes 14 and 16 split at Ucross. U.S. Route 16 generally maintains the original route of the Black and Yellow Trail over the Bighorn Mountains; U.S. Route 14 continues northwest to Sheridan, Wyo., then crosses the Bighorn Range via Dayton and Burgess Junction to Lovell in the Bighorn Basin. Both routes ultimately access the East Entrance of Yellowstone National Park.

Due to the wide-open and undeveloped nature of the Wyoming landscape, the adventurous can still find and explore remnants of this historic road—so Go Ramble!

(Editor’s note: Special thanks to Peabody Caballo Mining, LLC, which made possible the publication of this article.)

Resources

Primary Sources

- Benson, Mrs. C.L. “The Black and Yellow Trail.” (poem). The [Newcastle] News-Journal, Nov. 18, 1920, 4.

- “Black and Yellow Trail Meritorious.” The [Sundance] Crook County Monitor, Oct. 16, 1913, 1.

- “Black and Yellow Trail Officials Visit Gillette on Tour to Park.” Gillette News, Aug. 8, 1919, 1.

- “Good Roads Convention.” The Buffalo Voice, June 21, 1912, 1-2.

- “Interstate Highway.” The Buffalo Bulletin, Feb. 8, 1912, 1.

- “Mark Black and Yellow Trail.” Buffalo Bulletin, May 12, 1921, 4.

- “Regarding the Black and Yellow Trail.” Gillette News, June 27, 1913, 1.

- “Road Work Resumed.” Worland Grit, March 19, 1936.

- “Road Work to Start Soon.” Worland Grit, March 5, 1936.

- “A Trail Blazed by the Immortal Custer: Building the Custer Battlefield Highway.” Sheridan Post, Jan. 25, 1920, 9.

- “200 Clinton, Iowa Scouts Visit Buffalo.” Buffalo Bulletin, July 14, 1921, 3.

Secondary Sources

- Gallup, James D. “A Brief History of the Black and Yellow Trail from 1912.” WPA #237. Wyoming State Archives and Records Management Section, 1936. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- King, Elizabeth. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form: Historic Motor Courts and Motels in Wyoming, 1913-1975. 2017. Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, Cheyenne, Wyo. (Hereafter SHPO).

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978.

- Massey, Rheba. Wyoming Comprehensive Historic Preservation Plan. 1989. Prepared for Archives, Museums and Historical Department, SHPO.

- ____________. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Log Cabin Motel. 1992. SHPO.

- Murray, Robert A. Class 1 Historic Resource Study, Vol. 1. Narrative History. 1978. Bureau of Land Management, Casper District, Casper, Wyo.

- ______________. Multiple Use in the Big Horns: The Story of the Bighorn National Forest (Vols. 1-2). 1980. Bighorn National Forest, Sheridan, Wyo.

- Rosenberg, Robert G. Historic Context: History of the Trail System in Yellowstone National Park. 2015. Yellowstone National Park and SHPO.

- ________________. Historic Evaluation of Sites along the WYDOT-Spotted Horse-Gillette, Horse Creek Section, Campbell County, Wyoming. 2004. Offices of the Wyoming State Archaeologist and Wyoming Department of Transportation. SHPO.

- _________________. Report of Historical Investigations, Historical Site Evaluations, Keyhole State Park, Crook County, Wyoming. SHPO.

- _________________. Report of Historical Investigations, WYDOT Project 0302090/PE21, Structure CLH, Buffalo-Gillette Rawhide Creek, Campbell County, Wyoming. 2017. SHPO.

- _________________. Wyoming Cultural Properties Form, Site 48JO1479, the Black and Yellow Trail. Wyoming Department of Transportation/Office of the State Archaeologist, Worland-Buffalo-West, Project No. 036-2(15). 1998. SHPO.

- _________________. Wyoming Cultural Properties Form, Site 48WA1220, Black and Yellow Trail; Report of Historical Investigations, Truss Bridge FML, County Road 580A, WYDOT Project No. N361A02, Washakie County, Wyoming. 2014. SHPO.

- Wyoming State Highway Commission, State of Wyoming. First to Thirteenth Biennial Reports of the State Highway Commission of the State of Wyoming, 1917-1942. (Each report covered a two-year period extending from Oct. 1 through Sept. 30).

Illustrations

- The images of the maps, the autos entering Yellowstone and the view of the Black and Yellow Trail in the Bighorn Mountains are from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The early photo of Spotted Horse, Wyo.is from the Campbell County Rockpile Museum in Gillette, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.

- The wagon photo is from the authors' collection, courtesy of the Olin Oedekoven family. Used with permission and thanks.

- The rest of the photos are from the authors. Used with permission and thanks.