- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Before The Numbers: Naming Wyoming’s Highways

Before the Numbers: Naming Wyoming’s Highways

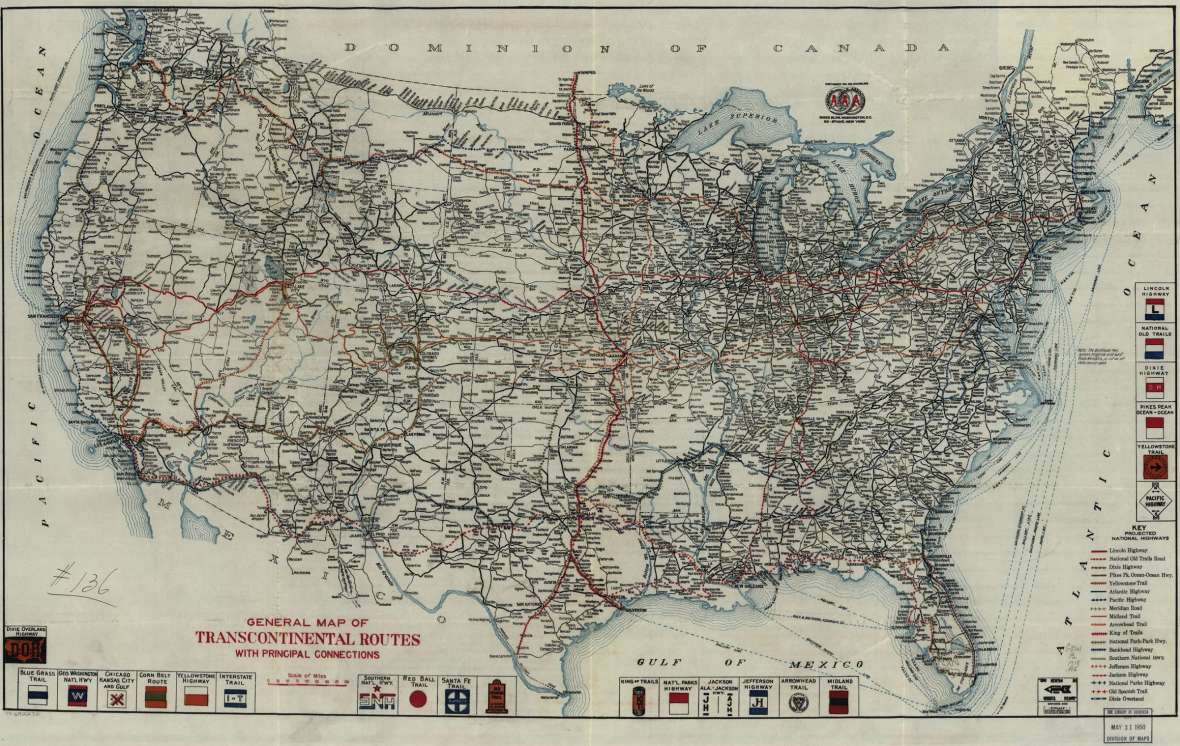

In a 1913 article, the Cheyenne State Leader sang the praises of good roads. It noted that the Lincoln Highway, the nation’s first transcontinental road, had recently chosen a route through Cheyenne. In fact, the newspaper said, Cheyenne was now on four major roads.

In addition to the Lincoln Highway, there was the “Gulf of Mexico to Yellowstone National Park Highway.” And the “AAA Coast-to-Coast road.” And the “National Highway of America, from NY to Washington to Philadelphia to Pittsburgh and thence through Kentucky and Kansas to Denver thence to Cheyenne where it joins the Lincoln Highway.”

The Lincoln Highway has been the subject of several books, and its Wyoming section has a thorough history on this website. The other three named roads are so obscure that they don’t even have any Google results. (As of May 2021, the “Gulf of Mexico to Yellowstone National Park Highway” and “AAA Coast-to-Coast road” generate zero results, and the “National Highway of America” generates four, none referring to this road.)

That’s not surprising. Named roads were a fad that once covered the nation and were then largely forgotten. The named-road era was a fascinating and important time in Wyoming history. People were discovering the wonders of auto travel. Marketers were discovering how to appeal to them. The result was wide-open competition in a new sort of gold rush, where the treasure was the automobile tourist. Nostalgia for the roads and their names still plays out today.

Why roads got named

The years from 1910–1930 were a frontier for the automobile. Previously, railroads had dominated long-distance travel. Cities were born, and fortunes made, based on the route of the train. How else could farmers send out products or receive mail-order essentials? Railroad monopolists became both wealthy and politically powerful.

Then arose independent car ownership, a potentially democratizing alternative. But as autos became dependable enough to take you more than a few miles, questions arose. Which routes should you travel? How would you know how to find them? Would they offer sufficient food, lodging, gasoline, or repair services?

The Lincoln Highway presented one model for answering those questions: an automaker-funded national association chose a coast-to-coast route, developed a logo, marked the route with signs, and wrote a guidebook. But soon competitors discovered that any such long-distance road had value to the communities it passed through—which meant that those communities might be willing to fund it.

A road association could collect advertising fees for a map or booklet, use some of that money for signs and related activities, and still have some of that money left over for the promoter’s profit. Thus the named-road business became a sort of Wild West: an unregulated frontier where an entrepreneur’s success depended on some combination of brains, romanticism, organization, chutzpah, wealth, and honor (or lack thereof).

What’s left a century later is mostly the romanticism: a fun collection of stylized logos and evocative road names. Many of these roads passed through Wyoming. After all, the state boasted both relatively easy routes through the Rockies and the raw materials for romantic dreams.

Trails to Yellowstone

Cody, Wyo.’s Gus Holm (sometimes spelled Holms or Holmes or even Holm’s) was the “chief good road booster of all Wyoming,” according to his hometown Park County Enterprise. In the summer of 1913 he drove a Studebaker 1,963 miles on the proposed Black and Yellow Trail and the Billings-Cody Way.

Based in Deadwood, South Dakota, the Chicago, Black Hills and Yellowstone Park Highway Association was knitting together a Black and Yellow Trail across the Bighorn Mountains. Promoters in central South Dakota hoped that Chicagoans would spend money in their towns on the way to the national park. Holm volunteered as a “pathfinder” to help select the Wyoming route and upgrade its conditions.

But the Black and Yellow Trail faced competition. The Twin Cities–Aberdeen–Yellowstone Park Trail, organized at a conference in Lemmon, South Dakota, in 1912, soon lengthened its route “from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound,” and shortened its name. The “Yellowstone Trail” would take Chicagoans, and others, across the northern reaches of South Dakota, and then into Montana, following the Yellowstone River to avoid crossing the Bighorns.

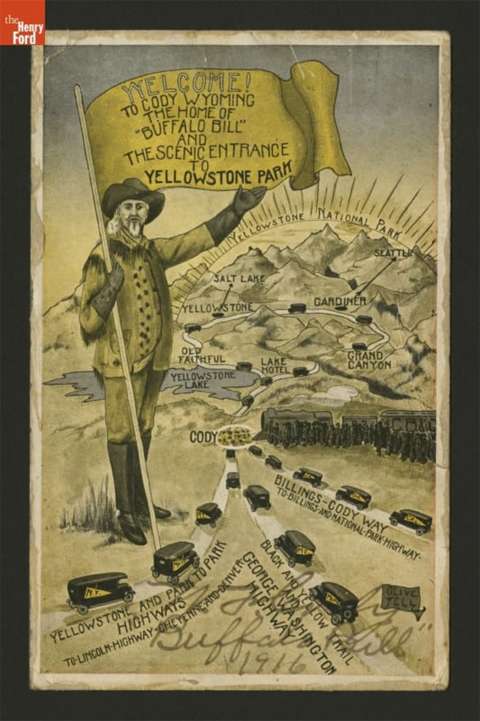

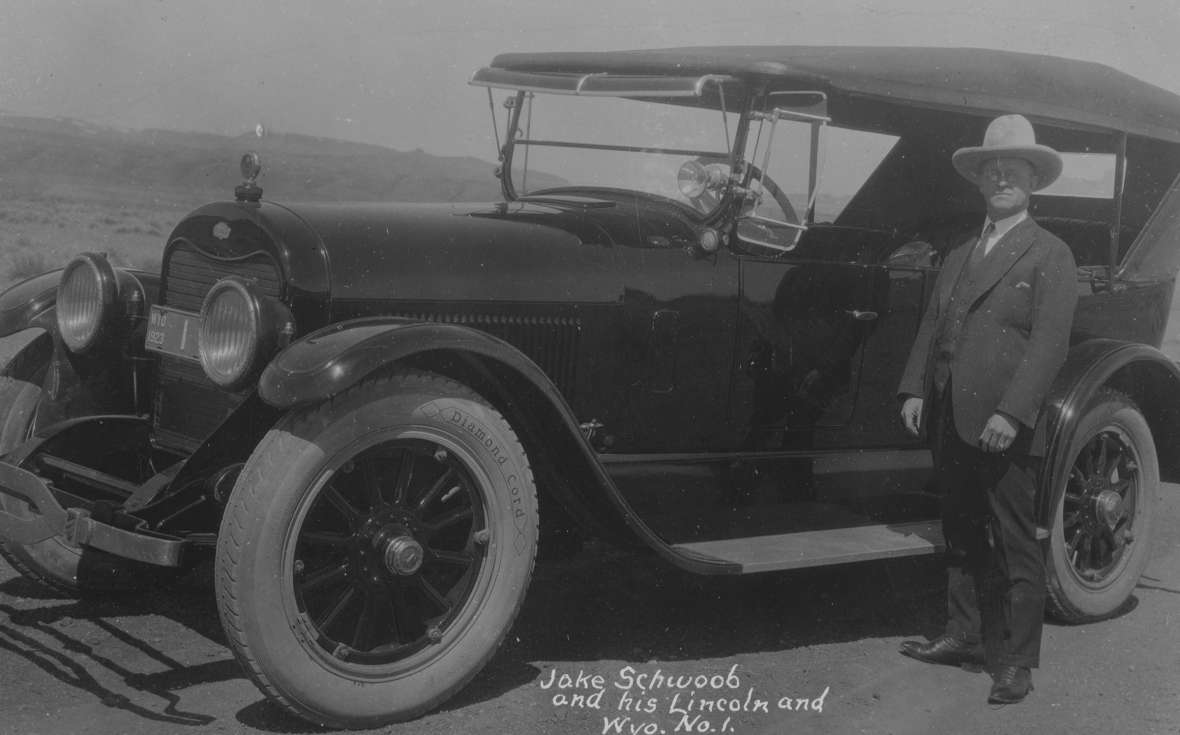

Holm—along with Cody Studebaker dealer Jacob M. “Jakie” Schwoob—wanted to position Cody on both routes. In addition to his work for the Black and Yellow Trail, Holm organized the Billings-Cody Highway Association to encourage construction of the Billings-Cody Way, an auto route that followed the 1901 Burlington Rail route from Montana south to Cody via Powell.

In February 1913, Holm led a Cody contingent to a Yellowstone Trail conference in Miles City, Montana. They proposed that instead of following the Yellowstone River along the Northern Pacific railroad tracks to Livingston, Montana, and the north entrance to Yellowstone Park, the Trail should enter Yellowstone via Cody. Apparently the conference-goers were impressed. But at the next conference, in Forsyth, Montana, in June, representatives from Livingston responded, and carried the argument.

But Holm had another option as well. That same year, promoters led by M. R. Collins of Douglas, Wyo., were sketching out a totally different road called the Yellowstone Highway. It ran from Denver through the newly established Rocky Mountain National Park to Yellowstone. (It too ran through Cheyenne, but was not announced until after the State Leader article was published.) When this Yellowstone Highway published an "Official Route Book” in 1916, the text was copyrighted by the organization’s president, “Gus Holm’s.”

All the attention to Yellowstone was rather ironic. When Collins made his pathfinder trip to Yellowstone in 1913, he had to stop at the east entrance to the park. Automobiles were not allowed to enter.

Steve Mather’s endorsement

At the time, almost all Yellowstone visitors arrived by train. Many took the Northern Pacific to Gardiner, Montana, where an elegant station designed by Robert Reamer, architect of the Old Faithful Inn, stood opposite the entrance arch. Some travelers took the Oregon Short Line, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific, from Salt Lake City to West Yellowstone. And others took the Burlington Route to Cody. All then toured the park on stagecoaches. To transport tourists and supplies, the park managed a herd of more than 7,000 horses.

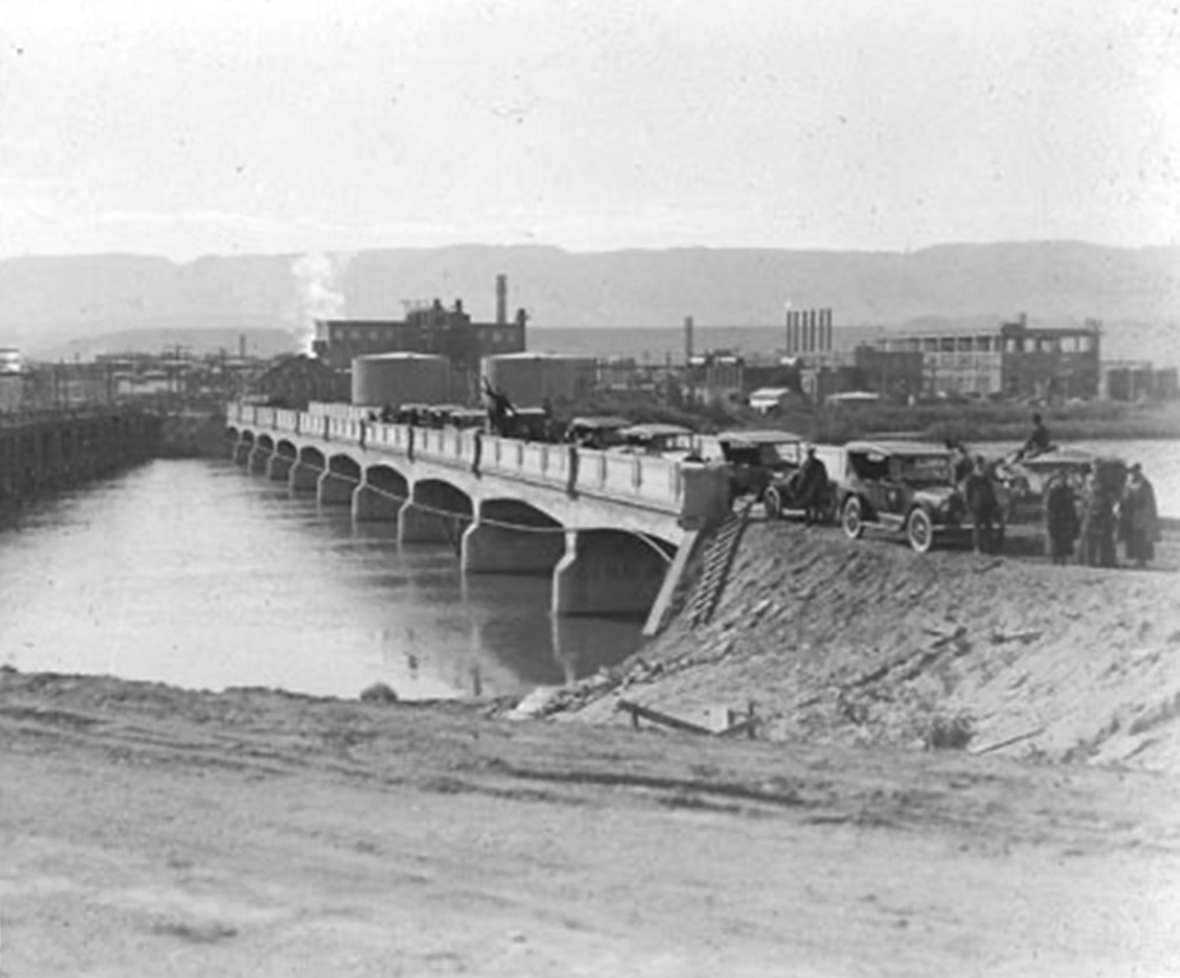

Yellowstone first admitted automobiles on August 1, 1915. It had spent three years strengthening bridges, installing culverts, building retaining walls, and otherwise upgrading its road system to handle automobiles. The money—one estimate was $2,265,000 to reconstruct the entire system—came from the Army, which was then managing the park.

A month later, Steve Mather and Horace Albright came to visit. Mather was a mercurial millionaire industrialist and Sierra Club member who had agreed to help the Department of Interior organize what would become the National Park Service. Young Albright was his hyper-organized right-hand-man.

After formally dedicating Rocky Mountain National Park, the two men took a train from Loveland, Colorado, to Cody. There Mather decided to take a stagecoach, rather than an automobile, to Yellowstone’s east entrance. He was curious how the mix of vehicles was working out. As Albright later wrote, “We were traveling right along, bumpy and uncomfortable but moving at a pretty good clip, when we came on a string of autos. They were having a terrible time trying to get up a steep grade; the road was just one big muddy mass of ruts. Our stagecoach was passing them neatly.” Albright found it quite amusing.

It turned out that the cars were from the Park-to-Park Highway Association, a successor to the (Colorado-and-) Yellowstone Highway group. Mather and Albright had met with them in Denver, and now they’d driven all the way here. Rather than amused, Mather was embarrassed at the condition of the road. He had pushed for autos to be allowed into Yellowstone, but what was the point if you couldn’t even get there?

In a conference in Yellowstone later that week, Mather encouraged the automobilists. He wanted to boost and coordinate long-distance highways so that people would visit national parks and support them politically. His annual reports regularly highlighted the activities of named roads that went to or near national parks. Mather also teamed with publicists for railroads. He marketed the national parks as effectively as he had marketed the product that made him a millionaire, 20 Mule Team Borax.

With follow-up meetings in subsequent summers, the promoters of the Yellowstone Highway teamed with other groups to connect 13 national parks in the National Park-to-Park Highway. Mather called it the nation’s “greatest scenic drive.” On August 26th, 1920, a party of twelve motorists formally inaugurated the road with a 76-day tour beginning with the Denver-to-Yellowstone trek through Wyoming.

Accompanying infrastructure

To accommodate automobiles, Wyoming needed to build and improve roads. However, to accommodate automobile travelers, Wyoming also needed hotels, restaurants, retail stores, gas stations, and repair shops. Furthermore, where such establishments had previously catered to a local clientele, the arrival of early auto tourists demonstrated that many of these facilities failed to meet national standards.

For example, in July, 1916, Mather and Albright returned to Wyoming as Congress debated the National Park Service bill that they had co-written. On July 21, Mather, his wife Jane and some friends arrived in Thermopolis by train. Mather and the Yellowstone Highway Association were eager for their road to come through Thermopolis and make its hot springs an attraction as big as those of Hot Springs National Park in Arkansas.

Albright, who arrived early to scout it out, later recalled his disappointment in Thermopolis’ “odd wildlife ‘zoo’ (with aroma arising from a handful of moth-eaten elk, deer, bison, a mother bear, and two cubs); the raw, hot, dust-laden wind that blew incessantly; and the bug-ridden hotel.”

The party then motored to Cody, where their experiences at the Irma Hotel were even worse. Its kitchen was “about the dirtiest, most unsanitary place I had ever seen,” Albright wrote. Jane Mather found bugs crawling in her bed and decided to sleep in the lobby. Steve Mather found two men sleeping in his bed. When he complained, the clerk told him to “make your bedfellows move over.” Meanwhile Albright was “awakened by some strange man crawling into my bed, falling asleep immediately, and giving off the loudest snores I had ever heard.”

The next day they stopped for lunch at Pahaska Tepee, which like the Irma was owned by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. It was, Albright wrote, “horrible, greasy, inedible food served by loud, boisterous, grimy, but glitzy waitresses.” When Buffalo Bill’s Wild West visited Washington the following year, Mather chewed out the celebrity for the “sad conditions” of his establishments, and Buffalo Bill vowed to remedy them.

The good news about that 1916 trip was the condition of the road. They could take a car rather than a stagecoach, and not get stuck in mud. Albright wrote, “The road to Yellowstone was amazingly good compared to 1915.”

A plethora of roads

The National Park-to-Park Highway, Lincoln Highway, and Yellowstone Trail were all supported by powerful, well-funded marketing organizations. These roads thrived in the public imagination. The attention spurred physical improvements, which allowed them to thrive in real life as well.

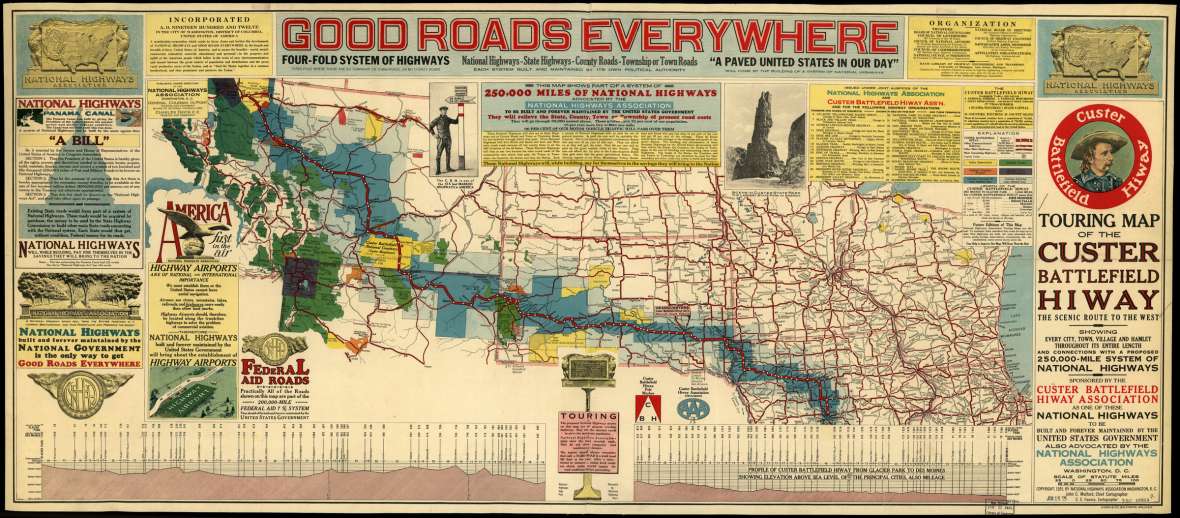

A second tier of roads was slightly less famous but still successful. This tier included the Black and Yellow Trail and the Custer Battlefield Highway. This latter route, established in 1919, went from Omaha, Neb. (later Des Moines, Iowa) to Glacier National Park, also passing through its namesake national cemetery. It thus traversed northeast Wyoming, from Beulah to Parkman. Just as the Black and Yellow Trail competed with the Yellowstone Trail with a route across central rather than northern South Dakota, this route, based in Mitchell, S.D., competed with both by taking an even more southerly route, corresponding to today’s I-90. Passing through Sheridan also represented a new route for a Wyoming portion of a national highway.

Several other second- or third-tier named roads originated in Yellowstone, although they did not traverse any other part of Wyoming. These included the National Parks Highway (different than the Park-to-Park highway, this was North Dakota’s competitor to the Yellowstone Trail, and was sometimes known as the Red Trail), the Geysers-to-Glaciers Trail, the Yellowstone-Glacier Beeline Highway, the Regina-Yellowstone Trail, and the Utah-Idaho-Yellowstone Highway.

In a third tier, roads were announced, named, and sometimes even platted, but never gained much momentum. For example, the Atlantic-Yellowstone-Pacific Highway was announced in 1923 in Sioux Falls, S.D., as yet another Chicago-to-Yellowstone highway. But its route was apparently only ever blazed from Chicago to Sioux Falls, thus giving it the unfortunate status of never reaching any of the three destinations in its name.

The George Washington National Highway, based in Omaha, Neb., ran from Savannah, Ga, to Seattle, Wash. In 1916 its president Percy A. Wells made the dubious boast that it was “the only highway that intersects every other highway.” A 1916 postcard and 1922 map show it coinciding with the Black and Yellow Trail through Buffalo, Worland, Greybull, and Cody, Wyo. I.S. Bartlett’s 1918 History of Wyoming celebrates Moorcroft, Wyo., “at the junction of two noted automobile routes—the George Washington Highway and the Black and Yellow Trail.” But then this highway largely disappears from the historical record.

In 1919, the mayor of Bearcreek, Mont., Dr. J.C.F. Siegfriedt (1879–1940), sought to build yet another road to Yellowstone—the Black and White Trail. Its Wyoming portion would have roughly followed the route of today’s U.S. 212, the Beartooth Highway from Red Lodge, Mont. through Wyoming to Cooke City, Mont. But Siegfriedt was trying to build a road from scratch, rather than re-labeling and marketing an existing route. He sold “subscriptions” but soon ran out of money. The Black and White Trail became a series of abandoned switchbacks up the side of a neighboring mountain. Does it count as a named highway if no tourist ever drove it? Does it count as Wyoming history if intended to traverse Wyoming but never did?

End of an era

In the mid-1920s, the explosion of named highways led to confusion. At chokepoints such as Cheyenne, Moorcroft, and Cody, signposts for competing highways crowded the roadsides. The purpose of named highways had been to help drivers select the best road, but there were now so many options that the purpose was no longer being served. Furthermore, merchants would get hit up by several competing promoters. In the East, the situation was even worse, especially around Chicago where all the competing Dakota routes funneled into the same corridor.

The market had failed to sort itself out in an orderly fashion. Competition begat chaos. Furthermore, the federal government was now funding most long-distance road construction, and it wanted to exert top-down control. It laid out the numbered system of U.S. routes. Several road promoters protested that not only could they lose their livelihoods, but numbers lacked the romance of road names. (Today, fans of the famed Route 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles might disagree.)

The numbers got assigned based on logic and politics rather than romance or commerce. Thus parts of Wyoming’s U.S. 14 and U.S. 16 are the old Black and Yellow Trail and parts of each are the old Custer Battlefield Highway. U.S. 30 follows the old Lincoln Highway but departs it at Granger Junction. The old Parks-to-Parks Highway is now I-25 from Cheyenne to Casper but U.S. 20 from Casper to Yellowstone.

Numbers are now an official standard. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials has a Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering, to go along with its standards for design, construction of highways and bridges, materials, and many other technical areas. The standards ensure consistency across jurisdictional lines for not only tourists, but also first responders.

Winning nostalgia

In 1988, Cody tourism businesses wanted to promote a route to Yellowstone’s northeast entrance (in addition to its well-known route to the east entrance). Wyoming State Highway 296 through Sunlight Basin, though only partially paved, provided dramatic views. It also roughly followed the route of the 1877 flight of the Nez Perce. Cody wanted to call this 47-mile stretch the Chief Joseph Scenic Highway. The Wyoming State Highway Commission (now the Wyoming Transportation Commission) agreed to back the plan.

The Chief Joseph hooks into the Beartooth Highway, perhaps Wyoming’s most famous named road. This summer-only scenic drive reaches nearly 11,000 feet but passes no year-round settlements in its 38 Wyoming miles. Ironically, however, its name is only informal. The highway was built as U.S. 12 in the early 1930s and was briefly labeled U.S. 312 before becoming U.S. 212 in 1962. Furthermore, the enabling legislation didn’t make clear who should be responsible for its reconstruction and maintenance, a status which continually keeps it in the news as the “orphaned highway.”

In 1998, the federal highway bill contained new language to provide funding for national scenic byways. It’s not much money, says John Davis of the Wyoming Department of Transportation. “But a little federal money for signage and safety can serve as a catalyst to improve these roads and aid tourism in surrounding communities.”

Counties, tribes, agencies, and other organizations nominate potential named roads to the Federal Highway Administration. For example, in 2002, the Beartooth Highway finally received an official name, the Beartooth All-American Road. (Furthermore, since 1997, a steering committee of interested parties has coordinated to provide for the orphaned highway’s upkeep and improvement.) In 2021, the Flaming Gorge – Green River Basin Scenic Byway became Wyoming’s second All-American Road.

Meanwhile, 20 smaller scenic byways and backways dot every region of Wyoming, from the Big Spring Scenic Backway north of Kemmerer to the Wyoming Black Hills Scenic Byway north of Newcastle, and from the Seminoe-Alcova Backway north of Sinclair to the Red Gulch-Alkali Backway south of Shell.

Like the original named roads, the purpose of scenic byways is to promote tourism. These aren’t trucking routes, or clogged with commuter traffic. Instead, rural promoters hope that tourists will enjoy the drive and spend money on the way. It’s nostalgia in the best sense of the word, reclaiming the joy of recreational auto travel.

You could thus think of scenic byways as a retro fashion. But there are two or three times as many named byways today as there were named highways in the golden era. And with population growth, they surely carry far more traffic. Named roads provide an example of nostalgia for a thing becoming a bigger phenomenon than the thing itself ever was.

Resources

Sources

- “Atlantic, Yellowstone, Pacific Highway,” Encyclopedia Dubuque. Accessed April 1, 2021 at http://www.encyclopediadubuque.org/index.php?title=ATLANTIC,_YELLOWSTONE,_PACIFIC_HIGHWAY.

- “Flaming Gorge – Green River Basin Scenic Byway Designated as All-American Road,” SweetwaterNow, February 19, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2021 at https://www.sweetwaternow.com/flaming-gorge-green-river-basin-scenic-byway-designated-as-all-american-road/.

- “National Park to Park Highway Association,” Better Roads and Streets, Volume 6, September 1916, pp. 42-44. Accessed April 1, 2021, at https://books.google.com/books?id=6bG8b_-ER2sC&pg=RA7-PA38&lpg=RA7-PA38&d

- “Northwestern Association’s Fourteenth Annual Meeting,” The Hotel Monthly, vol. 24, August, 1916, accessed April 6, 2021, at https://books.google.com/books?id=BV5GAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA7-PA43&dq=%22george+washington+highway%22+omaha+savannah&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj369ej_OnvAhXPrZ4KHbdyC5sQ6AEwAHoECAAQAg#v=onepage&q=%22george%20washington%20highway%22%20omaha%20savannah&f=false, pp. 42-43.

- “Report of the Director of the National Park Service,” Washington DC: Department of the Interior, Nov. 12, 1918, p. 819, accessed April 8, 2021 at https://books.google.com/books?id=_R1IAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA819

- Albright, Horace M., and Marian Albright Schenck, Creating the National Park Service: The Missing Years. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999.

- Bartlett, I.S., editor, History of Wyoming vol. 1. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1918. Accessed April 1, 2021 at https://sites.rootsweb.com/~wytttp/history/bartlett/chapter33.htm.

- Carr, Ethan, Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture and the National Park Service, Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

- Clayton, John, “Origins of the Beartooth Highway,” in Stories from Montana's Enduring Frontier. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2013.

- Culpin, Mary Shivers. The History of the Construction of the Road System in Yellowstone National Park, 1872-1966. Historic Resource Study, Volume I. Denver: Rocky Mountain Region, National Park Service, 1995. Accessed April 8, 2021 at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/yell_roads/hrs1-5.htm.

- Franzwa, Gregory M. The Lincoln Highway in Wyoming. Tucson, AZ: Patrice Press, 1999. Our quote of the Cheyenne State Leader is taken from p. 9. Although Franzwa gives neither title nor date of that article, it is apparently from early October, 1913.

- Iowa Department of Transportation, “Historic Auto Trails: Custer Battlefield Highway,” Accessed April 1, 2021, at https://iowadot.gov/autotrails/custerbattlefieldhighway.

- Kulbacki, Michael, Bert McCauley and Steve Moler, “An Orphaned Highway,” Public Roads, Vol. 70 No. 1, July/August 2006, accessed May 14, 2021 at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/06jul/03.cfm.

- Official route book of the Yellowstone highway association in Wyoming and Colorado. Chicago: Wallace Press, 1916, accessed March 28, 2021at https://archive.org/stream/officialrouteboo00yell/officialrouteboo00yell_djvu.txt,.

- Ridge, Alice A. & Ridge, John William. Introducing the Yellowstone Trail: A Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound, 1912–1930. Altoona, Wis.: Yellowstone Trail Publishers, 2000.

- Shankland, Robert, Steve Mather of the National Parks. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970.

- Wade, Brandon (dir), Paving the Way: the National Park-to-Park Highway. Depth of Field Productions, 2009. Available from https://pavingtheway.tv/.

- Weingroff, Richard F. and Sherry Hayman, “Wondrous Rides Through Nature’s Wonders,” Public Roads, Vol. 80 No. 3, November/December 2016, accessed April 1, 2021 at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/16novdec/03.cfm.

- Weingroff, Richard. “From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System,” Federal Highway Administration Highway History, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/numbers.cfm

- Whiteley, Lee and Jane. The Playground Trail: The National Park-to-Park Highway. To and Through the National Parks of the West in 1920. Boulder: Johnson Printing, 2003.

- Wyoming Department of Transportation. “Scenic Byways,” accessed April 29, 2021 at http://www.dot.state.wy.us/home/travel/scenic_byways.html.

- Wyomingtourism.org. “Wyoming Road Trip: Western Heritage Along Our Scenic Byways,” accessed May 18, 2021 at http://www.dot.state.wy.us/files/live/sites/wydot/files/shared/Public%20Affairs/photos/Scenic%20Byways%20brochure%202013.pdf.

Illustrations

- The photos of the first cars entering Yellowstone, Gus Holm, the cars crossing the bridge in Casper and the cars by the Buffalo Bill Reservoir are all from the Park County Archives, Cody, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks to archivist Brian Beauvais.

- The postcard of Buffalo Bill with the named highways at his feet is from the Henry Ford museum. Used with permission and thanks. The author notes further that the image is fascinating for how it shows the town linking itself to Yellowstone and Buffalo Bill. It’s signed by noted Cody artist Olive Fell, who was just 20 years old in 1916. This particular card is of historical interest because Buffalo Bill himself sent it to Henry Ford.

- The 1918 national map of transcontinental routes and the1925 map of the Custer Battlefield Highway are from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The 1922 map of the Park-to-Park highway around the West is from americanroads.us. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Jake Schwoob standing beside his Lincoln is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and special thanks to archivist Nora Plant.