- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Greetings From Wyoming: Postcards and The Touri...

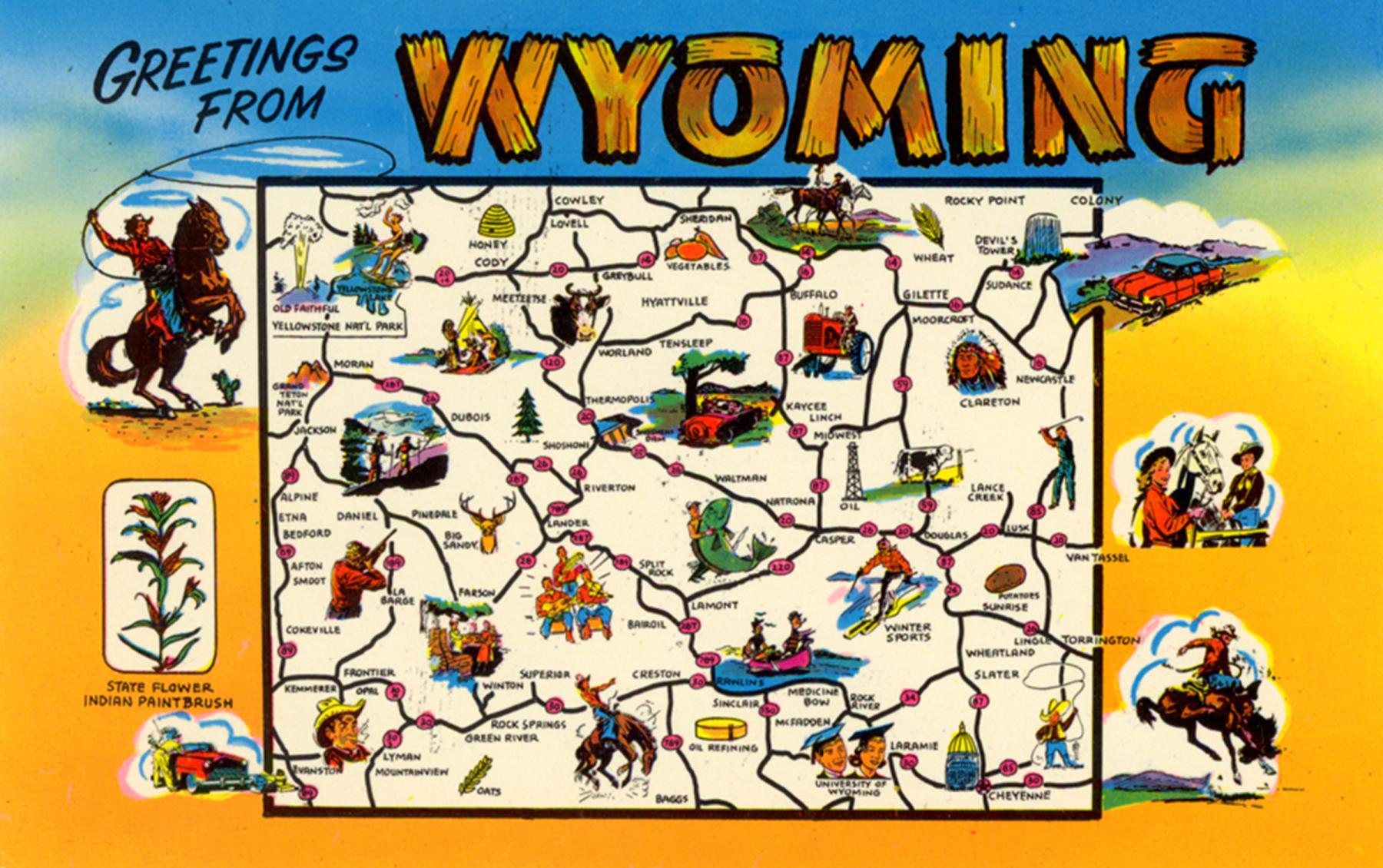

Greetings from Wyoming: Postcards and the Tourist Culture

Before the Civil War and even into the early 20th century, tourism was nonexistent for nearly all Americans, save for the wealthiest of the wealthy. While cities like New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Washington, D.C., New Orleans, Nashville and even Savannah, Ga. have always appealed to tourists, the West began to be trumpeted as a destination spot for average Americans only around 1900—and to a much larger extent after World War I.

Image

Up until the 1920s, perhaps an Eastern relative received a postcard from a wayward son in San Francisco, but for the most part, the West was something to be conquered, not visited. Even with the full development of the transcontinental rail network in post-Civil War America, travel and tourism were still largely limited to the upper classes, due to the cost and the time it took to cross the country by rail.

These vacations were not even referred to as tourism but were more like spas or cures the wealthy took to heal themselves mentally, physically and spiritually. In the Gilded Age, an average American simply couldn’t take a week off work to go from New York or Boston to see the Rocky Mountains, if that was even possible.

War, however, is often the mother of invention. The World War I economy expanded automobile production and birthed an American middle class with disposable income. The two would be married, and have not been separated nor divorced since. Like the Michelin Guide, the cultural phenomenon of the postcard is linked to car culture, travel and a commercial motive.

Postcards as advertisements

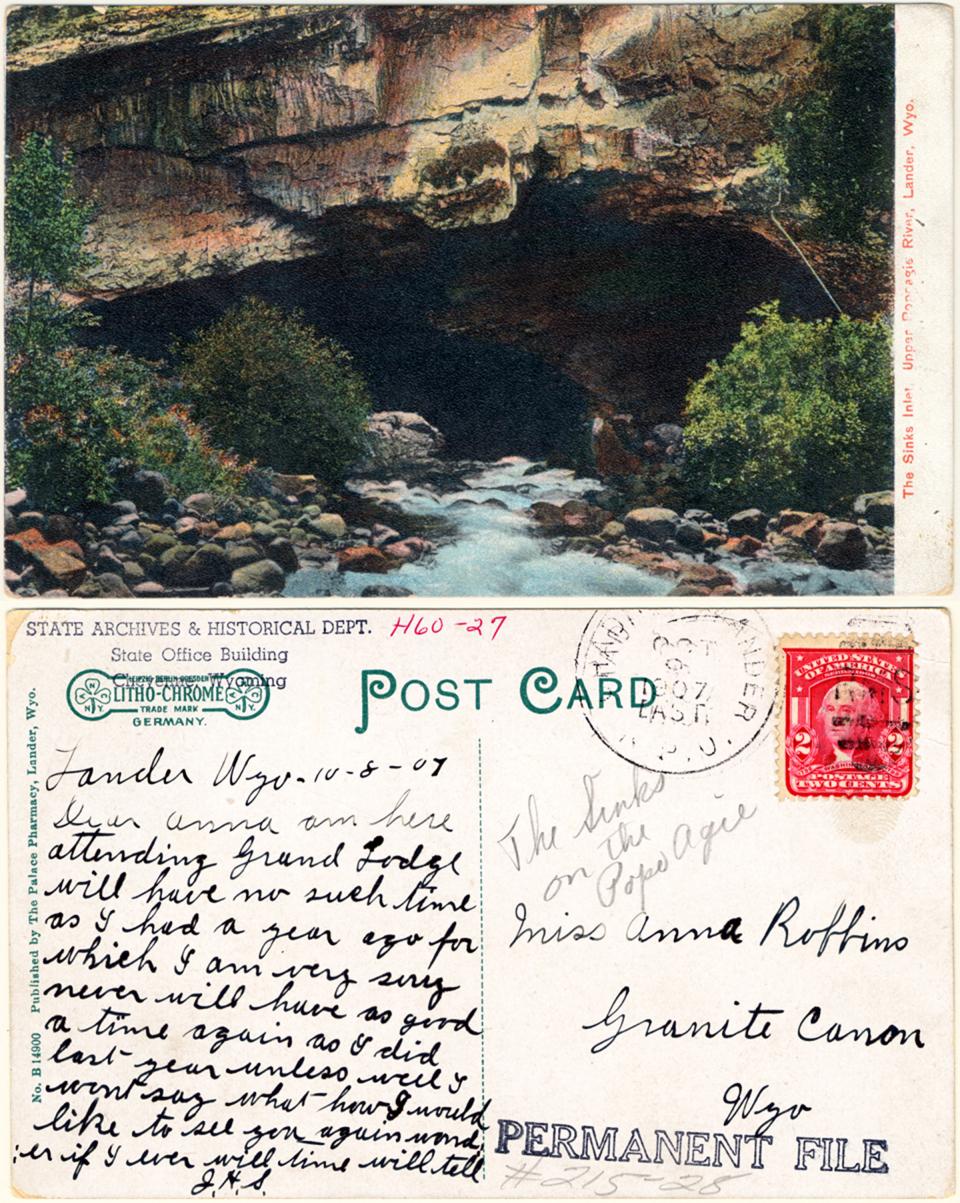

Postcards as we know them now in the United States date to 1861, when Congress began allowing people to send privately printed cards in the mail. In 1873, the government began producing postal cards, with space on one side for an address and on the other for a message, which could be mailed for the price of one cent. Privately printed cards cost two cents to mail.

The privately printed cards were used primarily for advertising, and were found mostly in big cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia or Chicago, and not meant as souvenirs. In 1898, the government allowed privately printed cards also to be mailed for only a penny, like the government ones. Most still were used for advertising, and some left a small space on the image side for a message to be written as well. The other side was still reserved for the address.

In 1907, a series of changes both in the United States and internationally allowed the address side to be divided in half, with a message on the left and an address on the right. Postcards have followed that pattern since—which still leaves room for a nice picture on the other side.

Image

Boosting the West

Thus, the purpose of the first postcards in Wyoming and the West was boosterism. Along with advertisements of businesses and job opportunities were claims such as that the new town of Worland, Wyo., was, as one postcard noted, “the most extensive and fertile region of the entire West…and destined to be the great commercial center of this vast region.” The Sheridan Post also reported that “Worland is a western wonder” with a community of “exceptionally progressive and public-spirited men, and without any question are the greatest boosters ever in one town.” As for agricultural opportunities, an early postcard assured people that “from the fact that the crops from one acre will sell for as much as the corn from three acres of land in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana: one can readily see that it is but a short time until the land will sell at $100 to $200 an acre.”

A final claim maintained that in no time, Worland “will be the most populous and thickly settled farming community in the United States.” Towns across the West made similar claims to entice settlers to pull up stakes and move, causing a small boom in many railroad towns’ inns, cafes, bars and restaurants. These catered to people on the move and would often have their own postcards on hand for travelers to send assurances back home that everything was great.

The need for better roads

Slowly and steadily in the first half of the 20th century, America’s roads expanded and improved, and reached their natural conclusion with the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, more commonly known as the Eisenhower Highway system. President Eisenhower had learned how difficult travel was in the West when, as a young army officer, he participated in the U.S. Army’s first Transcontinental Motor Convoy that left from Washington, D.C. on July 7, 1919.

Image

The convoy followed the Lincoln Highway, such as it was then, arriving in San Francisco on Sept. 6 after two arduous months. Eisenhower had observed the ease of travel on the German Autobahn during World War II. When he was president, as Cold War tensions increased, Air Force bases were being established across the West, including the F. E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne. Eisenhower knew that easy transportation in the West was extremely important. By the 1950s, the postwar economy was creating vastly expanded, car-purchasing middle class. Travel to the natural wonders of the West became truly accessible for the first time.

Postcards and cultural bias

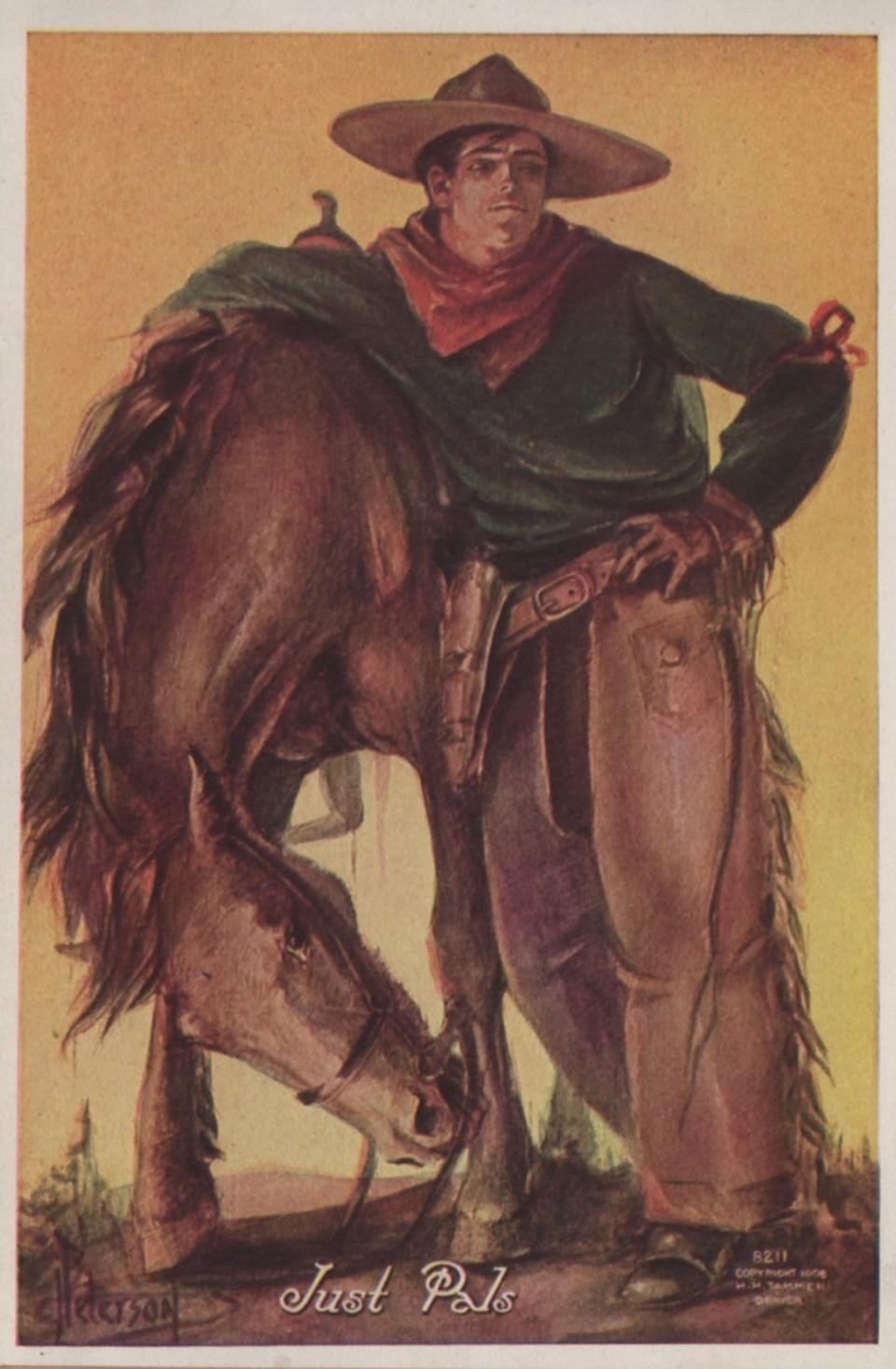

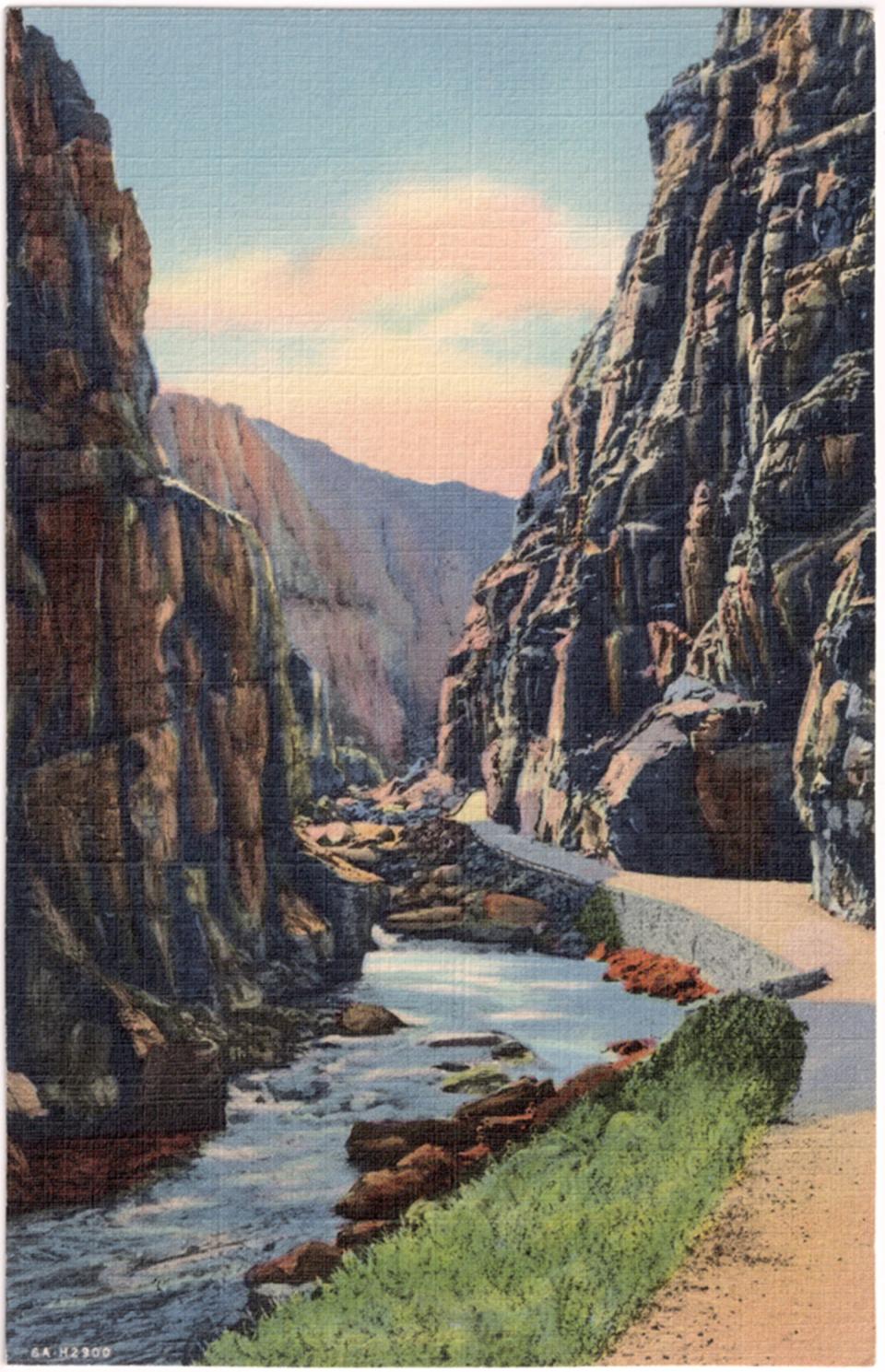

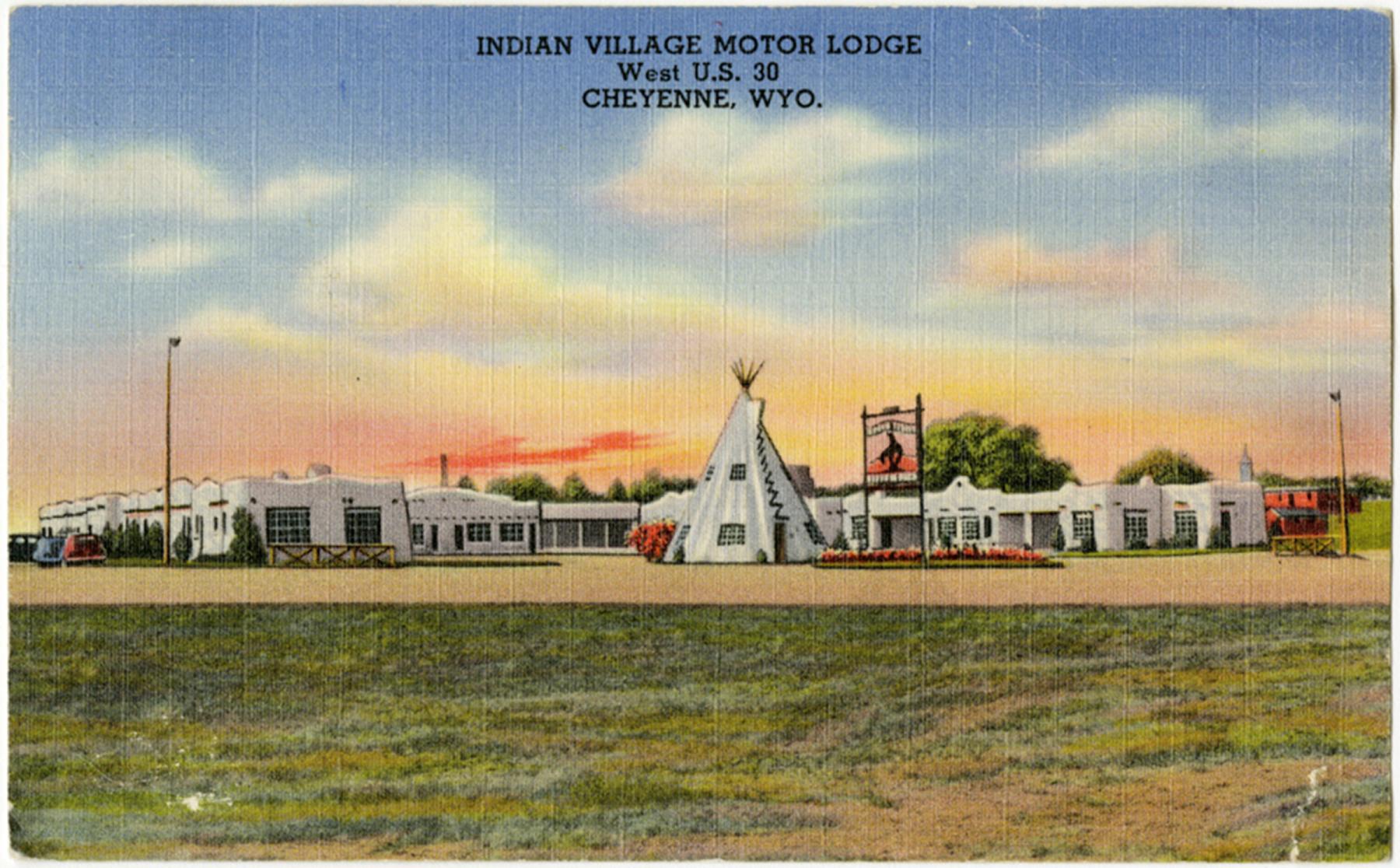

Postcards were used to market all sorts of tourist traps that sprang up along highways entering Wyoming. They were sold in the places where we still find them today: motels, hotels, gas stations and trinket and t-shirt shops. Most images on these early Wyoming postcards, just as today, are of the natural landscape or an idealized cowboy life.

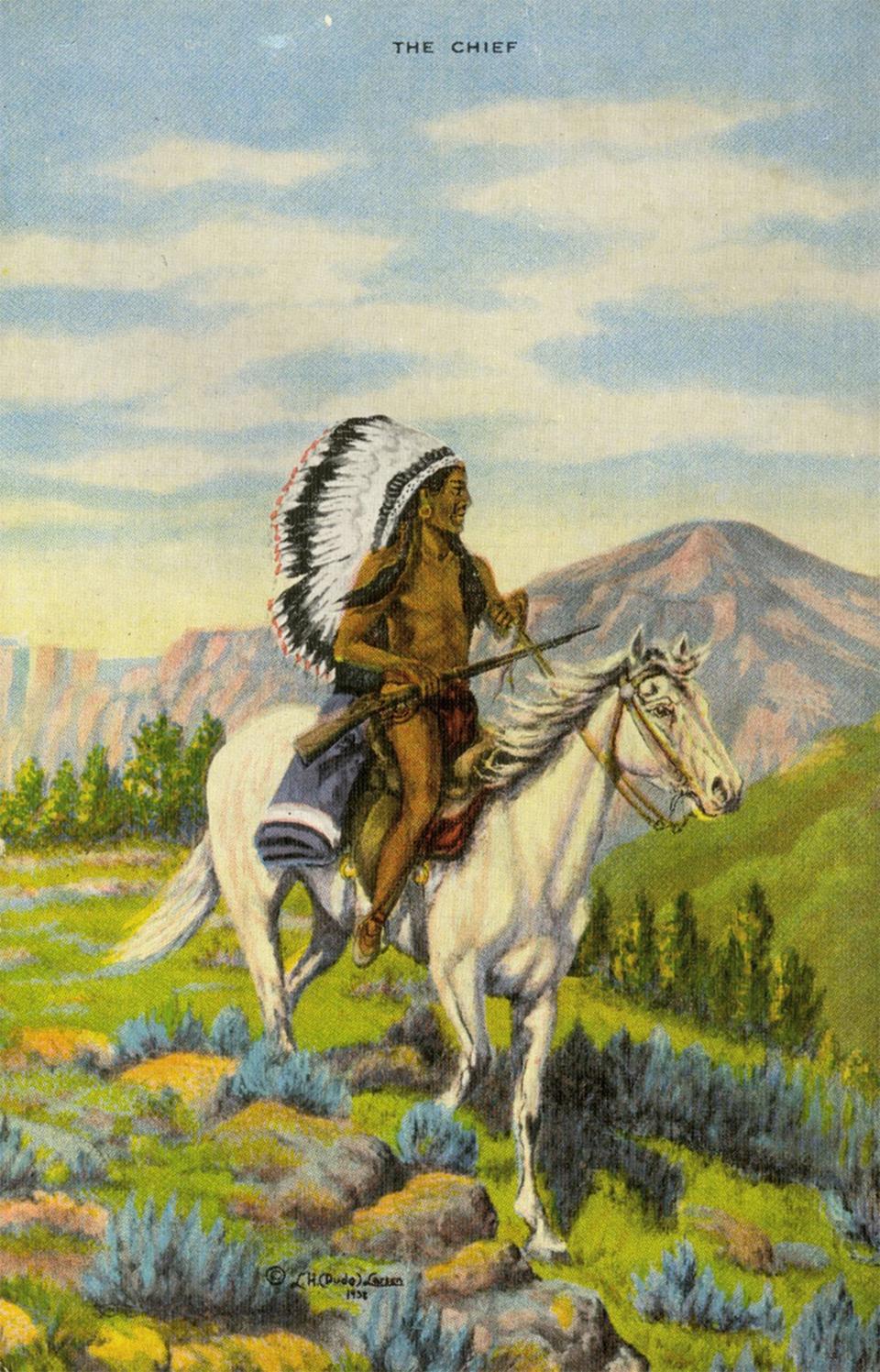

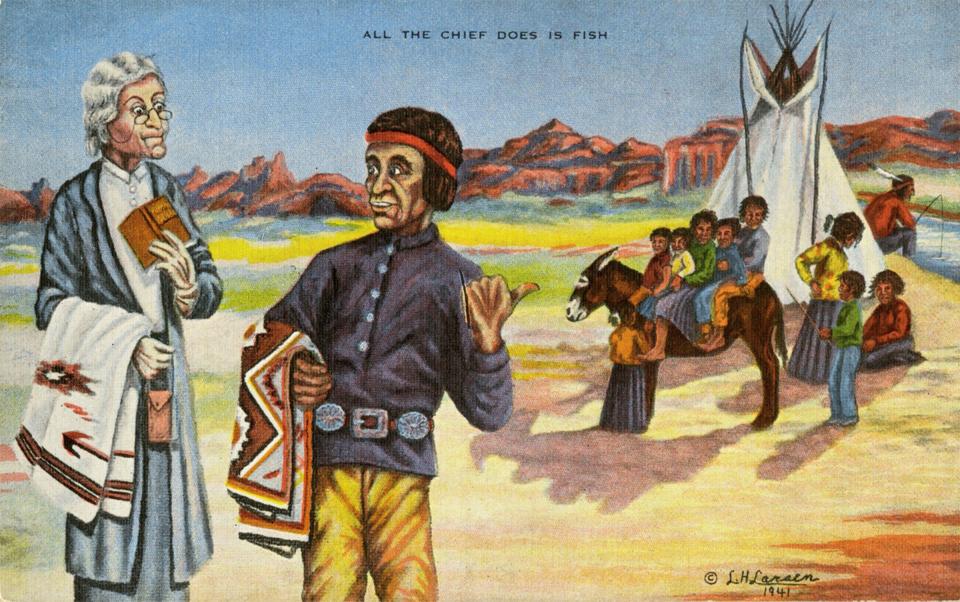

But one does not see African Americans or Mexican Americans, and Native Americans are portrayed only in a nostalgic or fetishized fashion—images of an idealized but vanished civilization, with things like no-longer used teepees or traditional dress, particularly women’s. Unlike Native men, the women were considered exotic, beautiful and, more important, non-threatening.

By contrast, Native American men were depicted as either indolent, if not downright lazy, or menacing and violent. Only occasionally were Native American men depicted as regal, and that was only when they were reified as a part of nature and something outside of and irreconcilable with White civilization. If one thinks about the fact that many other postcards are of the natural landscape and animal life, the stereotyping of Native Americans as primitive reveals itself as particularly malignant.

Postcards of Wyoming and the West show their producers’ and vendors’ choices of what to include and exclude, consciously or subconsciously. On these postcards are things like trout, broncs, elk, moose, bear and deer, mountains, lakes and streams, as well as hunters, fishermen, and hikers. There are also campers, RVs and other automobiles. That’s part of the point: Only with the development of the American highway system did access to the West become at least partially democratized as tourism to Wyoming boomed during the early 20th century.

In 1916, around 30,000 people visited Yellowstone National Park. Just 20 years later, more than 400,000 people came. Postcards offered visitors a vicarious role in the conquest of the West, one of the central narratives of American identity. These postcards present idealized versions of it. Travelers were offered the illusion of an American purity and an authentic experience.

Of course, by the time of easy travel to the West, few “authentic” Western experiences remained. Mass-produced postcards offered images of “authentic” Western experience as part of a national identity that visitors could send home back East.

The “national culture”

Something that most likely went completely unnoticed was going on during the early part of the 20th century. Postcards, and more specifically, postcards of the West, made this something visible: The national culture being created was accessible primarily to the White middle class. Who was included in the national identity was a combination of what was deliberate, what was systemic and what was accidental or subconscious.

Whites deliberately excluded Native Americans from that identity because Whites believed Natives could not be reconciled with American culture. The exclusion of minorities from the early creation of a national culture is the legacy of conquest, slavery and Jim Crow: The American middle class created in the late 19th century and through the wartime economies was almost exclusively White. Hence, White Americans were the only ones with the means to travel and partake of the “national” culture; they wanted their own real or imagined experiences reflected in their travels.

Not only did the poor and disenfranchised not travel to the same places as middle-class Americans. The very wealthy also did not often frequent locations marked by mass culture. Ultimately, White middle class members reproduced their experiences in postcards in order to send their sights and stories around the country. Before the smart phone, the postcard was one of the main ways people did this.

Image

Image

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support that in part made this article possible.]

Resources

- Limerick, Patricia Nelson. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987.

- Nickerson, Greg. “Industry, Politics and Power: The Union Pacific Railroad in Wyoming.” WyoHistory.org, accessed May 11, 2023 at https://wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/industry-politics-and-power-union-pacific-wyoming.

- “Postcard History.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, accessed May 11, 2023 at https://siarchives.si.edu/history/featured-topics/postcard/postcard-history.

- Pyne, Lydia. Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network. London: Reaktion Books, 2021.

- Shaffer, Marguerite. See America First: Tourism and National Identity 1880-1940. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.

- Schwantes, Carlos A. “Tourists in Wonderland: Early Railroad Tourism in the Pacific Northwest.” Columbia Magazine7, no. 4 (Winter 1993-1994).

- Willoughby, Martin. A History of Postcards: A Pictorial Record from the Turn of the Century to Today. Secaucus, N.J.: Wellfleet Press, 1992.

Illustrations

- The postcards of Bonnie Grey jumping over the car on King Tut, the “Greetings from Wyoming” card, the Indian Village Motor Lodge, the front and back of the Sinks Canyon card and the postcard of Wind River Canyon are all from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The postcards of the cowboy and his horse, catalogued as "Postcards: Folding Postcard Set, "Cowboys,” Undated, Box 88, Folder 9, J. S. Palen Collection, Accession Number 10472, and the card of the begging bear cubs, catalogued as "Three bears at the window of a car visiting Yellowstone," Photofile: Yellowstone-Wildlife, are from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The postcard of the mounted chief and the “All the chief does is fish” card are from the collections of the Washakie Museum and Cultural Center in Worland, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.