- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Wyoming Parkitecture

Wyoming Parkitecture

In 1904, when the Old Faithful Inn opened in Yellowstone National Park, it was immediately seen as a unique treasure of a building: rustic and luxurious, breathtaking yet casual, a monumental icon that fit perfectly into its surroundings.

Park Superintendent John Pitcher called the inn “a remarkably beautiful and comfortable establishment.” Without disagreeing, a Western Architect photo spread said, “The hotel is simply the rough product of the forest.” The inn quickly came to be a symbol of Yellowstone itself—so much so that the 1915 world’s fair in San Francisco featured a larger-than-life replica.

Indeed, this extraordinary building kicked off an entire architectural style: National Park Service Rustic, also known as “parkitecture.” Now more than a century old, parkitecture has exerted influence throughout the nation and world. Wyoming contains some of its best examples.

Harry Child’s gamble

A former mining executive from Helena, Montana, Harry Child (1857–1931) invested in farms, ranches, and the transportation and hotel concessions in Yellowstone. That last investment would become his legacy.

At the turn of the 20th century, Child’s high-class Yellowstone hotels—and the weeklong stagecoach tours that shuttled tourists among them—faced competition from other concessionaires who ran cheaper tours through less-formal tent camps. To make his businesses notably different from his competitors, Child decided to invest in the uniqueness and luxury of his hotels. A particularly glaring need was for accommodations near the Old Faithful geyser, one of the park’s most popular features.

For the design work, Harry chose little-known architect Robert Reamer (1873–1938). They met in January 1903, when Harry and his wife, Adelaide, were vacationing at San Diego’s grand Hotel del Coronado, where Reamer worked. Harry saw Reamer’s talent and appreciated his willingness to immediately relocate to Wyoming. Soon Reamer was busy on multiple Yellowstone assignments.

Most important on Reamer’s project list was the structure at Old Faithful, a quarter-mile west of the famous geyser. It’s not clear whether Child or Reamer first came up with the idea to build it as a ridiculously oversized log cabin. Harry had previously talked about “the rustic” and proposed collections of small huts, but by March, he set off for the nation’s capital to gain federal approval for Reamer’s drawings of a single structure.

Rustic and informal

A hands-on designer, Reamer supervised crews at Old Faithful through the summer of 1903 and the following winter—while also working on a major renovation of the Lake Hotel. The new Old Faithful Inn opened for the 1904 tourist season. Its most notable feature was its massive, seven-story lobby with walls of raw log surrounding a sixteen-foot-square fireplace of rough-cut rhyolite.

Reamer had taken a vernacular building style—one used by everyday folks for cheap shanties—and applied it to a new use: the high-end hotel. As part of that creative transformation, he brought light to the traditionally dark and dank log cabin, through dormers scattered across the inn’s great sloping roof. As the light sprinkled down—filtered through gnarled and twisted branches used for railings and other interior features—you could feel like you were in the bottom of a leafy forest.

The very notion of the multistory lobby, although common today, was another innovation for the time. The tall, airy space combined with the logs, lacy accents, and sunlight to blur the boundary between outdoor and indoor. The building’s monumental enormity matched the scope of the surrounding wilderness. Yet its natural materials complemented the surrounding scenery rather than trying to push it aside. Meanwhile, the interiors, designed by Adelaide Child, were warm, tactile and intimate, putting the building on a human scale.

Nationwide influence

The number of national parks in the United States more than doubled in the 1900s and 1910s. Most new parks needed hotels, and designers often followed Reamer’s lead. The creative tensions of this style—between outdoor and indoor, wilderness and luxury, crude and comfortable, natural and manmade—were perfectly suited to a national park. The parks celebrated unique American landscapes and the unique American character.

Previous park attempts to house wealthy visitors in comfort had always paled in comparison to the grand hotels of Europe, however. With this new emphasis on informal rusticity, an American national park hotel could express the park's, and the nation’s, own unique character.

For example, the 1910 Glacier Park Lodge used massive tree trunks, complete with bark, as central pillars in an expansive lobby that also featured an open firepit. The 1917 Paradise Inn at Mount Rainier aimed for similar rusticity, as did the 1924 lodges at Bryce and Zion and the 1927 Ahwahnee Hotel at Yosemite.

Meanwhile, as Harry Child’s full-time architect, Robert Reamer designed many Yellowstone buildings and renovations in a variety of styles. He used rustic stylings at a 1903 train station in Gardiner, Montana, and may also have contributed to the adjacent entrance arch. The train station was later demolished; the arch is now known as Roosevelt Arch, after Theodore Roosevelt, the president who laid its cornerstone.

Reamer’s 1904 remodel of the previously featureless Lake Hotel gave it a colonial feel, so much so that it became known as the Lake Colonial Hotel. Most intriguingly, his 1910 remodel of the previously unsightly Canyon Hotel used Prairie-style horizontal lines so well that critics speculate that Reamer may have known and been influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright. The Wright connection, while plausible given that Reamer was a teenaged draftsman in Chicago, is unconfirmed. The Canyon Hotel was demolished in 1960.

Dude ranches

There’s an indirect connection between National Park Service Rustic and the architecture of the dude ranching industry, which arose in the Jackson, Cody, and Sheridan, Wyo., areas in the 1900s and 1910s. Dude ranches evolved from working frontier ranches, and thus log cabins were familiar. Yet the visiting dude’s experience often centered on a trip to Yellowstone, so parkitecture on the dude ranch offered stylistic consistency.

In Jackson Hole, many of those historic dude ranches—including the Jenny Lake Lodge (Danny Ranch), the Bar BC, the 4 Lazy F (Sun Star) and the Murie Ranch (STS)—were later incorporated into Grand Teton National Park. However, at their construction, which was on private land with designs not subject to park service approval, they weren’t officially part of the National Park Service Rustic style.

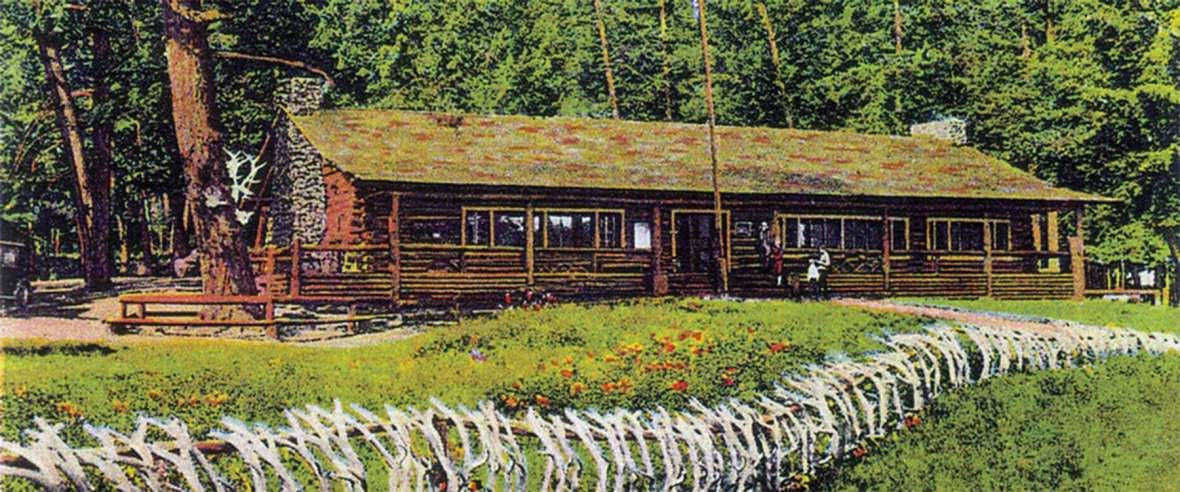

By contrast, the 1920 Roosevelt Lodge in Yellowstone, like Harry Child’s hotels, was constructed by a concessionaire and required federal approval. This structure, though, was modeled on dude-ranch architecture rather than directly on the Old Faithful Inn. Roosevelt Lodge features large stone chimneys and walls of logs that retained their bark. Inside, beams and rafters are exposed and stone fireplaces command attention. The oldest of the surrounding cabins have notched log walls, exposed rafter ends, and wood-shingled roofs.

Museums, too

Before the 1920s, most tourists visited Yellowstone in stagecoaches. Their drivers could enlighten them about the scientific or historical context to help explain wondrous features. But automobiles transformed the nature of national park tourism. With tourists riding now in their own vehicles, how would they gain that education?

Funded by the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Foundation and the American Association of Museums, a team led by scientist Hermon Carey Bumpus proposed a series of “roadside museums” to provide interpretation as close as possible to the features themselves. In Yellowstone from 1929 to 1932, architect Herbert Maier designed four such museums: at Fishing Bridge, Norris, Madison Junction, and Old Faithful. The last of these was later demolished.

Maier used battered rubble masonry, peeled logs stained a warm brown, and large decks built around existing trees. He loved using native materials to make it seem as if the buildings had grown organically from their surroundings. They are parkitecture, clearly influenced by the Old Faithful Inn. But like Reamer, Maier was innovating: applying the traditional vernacular log-cabin style to a surprising new function, the museum.

The roadside museums’ informality contrasted with the neoclassical theme of many urban museums—as did the very notion of constructing a museum adjacent to the natural feature it was interpreting, rather than in a big city. Bumpus believed that the real museum was the park itself, and the buildings merely offered labels for the unlabeled exhibits outside. In a sense, parkitecture facilitated a new learning style—Bumpus’ view of national parks as “roofless museums of nature”—which proved highly popular with the parks’ influx of middle-class automobile tourists.

Another new feature of the museums was that they were constructed by the government rather than a concessionaire. The Rockefellers requested anonymity, so funds appeared to come from the Department of the Interior. The notion of rustic, informal architecture had graduated from a characteristic that hoteliers thought visitors might enjoy to an official policy of the park service. This formal blessing occurred just in time for a massive, federally sponsored building program.

Parkitecture nationwide

In response to the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) mobilized 300,000 formerly unemployed youths to perform work on government-owned lands around the country. Some CCC crews worked in national parks, at national monuments and on other federal lands. Other crews helped develop facilities at state parks, under National Park Service supervision. Thus in the 1930s, parkitecture expanded beyond national park hostelries and museums to include administration buildings, maintenance facilities, picnic areas, and bathhouses in a variety of settings at the federal and state levels.

Herbert Maier, architect of the Yellowstone roadside museums, became an administrator shared between the Park Service and CCC. He developed a “patternbook” that showed state-park planners photographs and drawings of rusticated museums, shelters, amphitheaters, footbridges, and even culverts. Facilities throughout the country were often designed on Maier’s principles.

Guernsey State Park

One of the first parks to be developed under the Park Service–CCC partnership was Wyoming’s Guernsey State Park. Herbert Maier sent a regional inspector with the patternbook to Lake Guernsey—a new reservoir on the North Platte River in east-central Wyoming—to meet with project architects. Soon, the park’s thorough master plan became a showpiece of state-park design.

Lake Guernsey’s leading example of parkitecture is its 1939 museum, featuring native stone, massive timber trusses, hand-forged iron and a roof with hand-split cedar shakes. The museum was noted alongside Yellowstone’s Madison Junction and Fishing Bridge museums in Albert Good’s 1938 Park and Recreation Structures, a leading CCC resource. Good’s book, formally published, was an evolution of Maier’s informal patternbook.

Lake Guernsey’s leading example of parkitecture is its 1939 museum, featuring native stone, massive timber trusses, hand-forged iron and a roof with hand-split cedar shakes. The museum was noted alongside Yellowstone’s Madison Junction and Fishing Bridge museums in Albert Good’s 1938 Park and Recreation Structures, a leading CCC resource. Good’s book, formally published, was an evolution of Maier’s informal patternbook.

Near the museum, an elaborate 1936 picnic shelter and restroom known as the “Million Dollar Biffy” features a gable roof atop walls of massive blocks of battered sandstone. Other Lake Guernsey CCC efforts include bridges, roadside parking areas, spur roads, stone drinking fountains, barbeque pits, and administration and service buildings.

Devils Tower

Similarly, today’s visitor center at Devils Tower National Monument was constructed by the CCC in 1935 from ponderosa pine logs and other local materials. Built as a museum, it offers a large window framing a view of the tower.

Devils Tower’s first log structure was built in 1922, a three-walled shelter with a wood-shingled roof. As a national monument, Devils Tower was then very remote and poorly funded; this early use of native materials was probably motivated by convenience and cost rather than aesthetics. A 1931 log-on-stone custodian’s residence was the first at Devils Tower to be designed under official parkitecture standards. The visitor center was then designed to mimic the residence’s style.

Later reinterpretations

In the 1950s, the park service pivoted to favor Modernist architectural styles, which were simpler and less labor-intensive to construct. Modernism shaped the 1957 Canyon Village in Yellowstone, the 1955 Jackson Lake Lodge in Grand Teton National Park, and the 1966 State Bath House at Hot Springs State Park in Thermopolis, Wyo. A later, short-lived change to a Modernist-influenced “solar style” produced the 1976 Bighorn Canyon Visitor Center in Lovell, Wyo. Such buildings efficiently handled large crowds. But criticisms of their lack of romance lionized the old National Park Service Rustic style.

Thus today, many of the old parkitecture buildings, including the original Old Faithful Inn, are celebrated and lovingly restored. Architects designing other new buildings seek to take advantage of parkitectural nostalgia, with modern touches. For example, the 2007 Craig Thomas Visitor Center at Grand Teton National Park has raw timber columns in front of Modernist glass walls. Likewise, a description of the 2010 renovation of the Jackson Hole airport, located entirely within Grand Teton park, bragged of its “rustic elegance in non-traditional uses.” In other words, its innovation was to apply log-cabin stylings to another incongruous purpose: an airport.

When it first opened, the Old Faithful Inn was something brand new. It didn’t look like any hotel that had ever been built before. It brought the informal, close-to-nature American character directly into its design. It has been justifiably replicated and reinterpreted in many other places. But not surprisingly, this style originated and thrived in Wyoming, a place of natural wonders of epic scale.

Resources

Sources

- Barringer, Mark Daniel. Selling Yellowstone: Capitalism and the Construction of Nature. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002.

- Barringer, Mark. “Private Empire, Public Land: The Rise and Fall of the Yellowstone Park Company.” Ph.D. dissertation, Texas Christian University, 1997.

- Carr, Ethan. Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture and the National Park Service. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998, especially 277–296.

- Clayton, John. Wonderlandscape: Yellowstone National Park and the Evolution of an American Cultural Icon. New York: Pegasus, 2017.

- Culpin, Mary Shivers. For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People: A History of Concession Development in Yellowstone National Park 1872–1966. Yellowstone National Park, WY: Yellowstone Center for Resources, 2003.

- Esperdy, Gabrielle, and Karen Kingsley, eds., SAH Archipedia, Charlottesville: UVaP, 2012—, Accessed Feb. 15, 2019, at http://sah-archipedia.org. Some buildings (with article authors) described by this useful resource include:

- Bighorn Canyon Visitor Center (Anthony Denzer): https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WY-01-003-0083

- Lake Guernsey State Park (Mary M. Humstone): http://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WY-01-031-0051

- State Bath House in Thermopolis (Mary M. Humstone): https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WY-01-017-0055

- Yellowstone’s Trailside Museums (Lesley M. Gilmore): https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WY-01-029-0034

- Good, Albert H. Park and Recreation Structures.United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1938, Part II:K: Markers, Shrines, and Museums. Accessed Feb. 15, 2019, at http://npshistory.com/publications/park_recreation_structures/part2k.htm.

- Harrison, Laura E. Soullière. Architecture in the Parks: National Historic Landmark Theme Study.Washington: National Park Service, 1987.

- “Historic Structure Report, Historical Data Section, Old Faithful Inn, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming.” Denver Service Center, Historic Preservation Branch, Midwest/Rocky Mountain Team, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1982.

- Maier, Herbert. "The Purpose of the Museum in National Parks," Yosemite Nature Notes(May 1926): 38.

- Naylor, David. “The Old Faithful Inn and its Legacy: The Vernacular Transformed” Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University, May, 1990.

- National Park Service. Accessed Feb. 15, 2019, at www.nps.gov.Particularly useful pages include:

- Devils Tower: https://www.nps.gov/deto/planyourvisit/visitorcenters.htm

- Jenny Lake: https://www.nps.gov/grte/learn/historyculture/jenll.htm

- Roosevelt Lodge: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/rooseveltlodge.htm.

- Trailside Museums: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/museums.htm

- “Parkitecture, Past and Present,” WholeTrees Structures, August 2, 2017. Accessed Feb. 15, 2019, at https://wholetrees.com/parkitecture-past-and-present/.

- Quinn, Ruth. Weaver of Dreams: The Life and Architecture of Robert C. Reamer.Gardiner, Mont.: Leslie and Ruth Quinn, 2004.

- Rogers, Jeanne. Standing Witness: Devils Tower National Monument: A History. Devils Tower National Monument, Wyoming: National Park Service, 2008. Accessed Feb. 27, 2019, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/deto/history/.

- Tweed, William, et. al. National Park Service Rustic Architecture: 1916-1942. National Park Service Western Regional Office, Division of Cultural Resource Management, 1977,accessed Feb. 15, 2019, at http://npshistory.com/publications/rustic-architecture.pdf.

- Wilson, Merrill Ann. “Rustic Architecture: The National Park Style,” Trends, (July, August, September, 1976).

- WyomingHeritage.org and Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. “Guernsey State Park.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed March 1, 2019, at /encyclopedia/guernsey-state-park.

Illustrations

- The photos of Old Faithful Inn and Lake Hotel are numbers 03271 and 14206 from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The A.L. George photo of Architect Robert Reamer and his foreman courtesy of National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park, YELL 89281-43. Used with thanks.

- Jim Peaco’s picture of the Old Faithful Inn interior, National Park Service photograph 17928d, is available on Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The 1927 postcard of Roosevelt Lodge is from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The postcard of the Canyon Hotel is from the National Park Service, via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Bumpus, Chorley and Maier at Madison Junction Museum is courtesy of National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park, YELL 44364. Used with thanks.

- The two photos of The Castle at Guernsey State Park are from Wyoming State Parks and WyomingHeritage.org. Used with thanks.

- The gallery photo of the Fishing Bridge museum is from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The gallery photo of the museum at Norris Geyser Basin is from waymarking.com. Used with thanks.

- The gallery photo of the museum at Madison Junction is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The gallery photo of Newell and Laura Joyner on the steps of the Devils Tower custodian’s residence, ca. 1933, is from a National Park Service gallery of photos of the Joyner family. Used with thanks.

- The gallery photo of the visitor center at Devils Tower National Monument is from KVO Industries, designers of the center’s exhibits. Used with thanks

- The interior photo of the Craig Thomas Visitor Center in Teton Park is from the Grand Teton National Park Foundation. Used with thanks.