- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Spring Creek Raid: The Last Murderous Sheep...

The Spring Creek Raid: The Last Murderous Sheep Raid in the Big Horn Basin

On April 2, 1909, seven cowmen attacked a sheep camp near Spring Creek, just south of Ten Sleep, Wyo., in the southern Big Horn Basin. The raiders killed three men—roasting two in their burning sheep wagon and shooting the third—kidnapped two others, killed sheep dogs and dozens of sheep and destroyed thousands of dollars of personal property. It was the deadliest sheep raid in Wyoming history.

Sheep raids had plagued Wyoming since the late 1890s, by which time sheep outnumbered cattle on Wyoming ranges. By 1909, at least six men had been killed, thousands of sheep had been slaughtered and many thousands of dollars of property destroyed, and yet there had not been a single conviction for a crime committed during a sheep raid.

Cattlemen were first to arrive in the Big Horn Basin, trailing in huge herds of cattle in 1879. They insisted their early arrival established a prior claim to the grass on the government land where their herds grazed. But the law said otherwise. Under federal land law in the early 1900s, both sheepmen and cattlemen had equal rights to the resources of public land. It was first come, first served, and neither group could claim any right of continuing use.

But it’s no surprise, given the rising numbers of sheep on the range in those years, that cattlemen were feeling pressure. Sheep already outnumbered cattle in Wyoming by the early 1890s; in 1894 there were 1.7 million sheep in Wyoming and 675,000 cattle. By 1909, the state’s peak year for sheep, there were more than six million sheep, and only 675,000 cattle.

The response of the cattlemen was to use violence to enforce their claims of precedence, wreaking terrible damage upon sheepmen and their property in the process. As the violence worsened, sheepmen determined to put a stop to the cattlemen’s vigilante behavior. In 1905, Wyoming sheep raisers formed the Wyoming Wool Growers Association, which made crucial contributions to the 1909 prosecution of the men who carried out the Spring Creek Raid.

Big Horn County, where Spring Creek was located, used money forwarded by the association to hire attorneys, cover the costs of trial and pay for essential actions such as concealing witnesses for their own protection and for the protection of the case. And the sheepmen contributed the services of their crack range detective, Joe LeFors, by then well known for his role in the conviction of Tom Horn, the notorious range detective executed for murder in 1903.

Big Horn County officials began an aggressive investigation of the Spring Creek Raid and quickly developed a list of suspects. A grand jury followed, forcing 100 people to testify in Basin City, the county seat. The testimony established solid evidence showing the complicity of seven men, all of whom were charged with murder and arson. After the arrests and jailing of these defendants, two of them turned state’s evidence, opening the secrets of the raiders to the prosecutors. The prosecution, it seemed, had put together an almost invincible case.

The two ranchers, two cowboys and a former cowboy waiting in the Big Horn County jail–George Saban, Milton Alexander, Tommy Dixon, Herb Brink and Ed Eaton–were confident that the cases against them would not even go to trial, and they would soon be released. All knew the dismal Wyoming history of the prosecution of sheep raiders. They also knew of other disastrous attempts to prosecute men engaged in extralegal activities. Those included the abortive attempt to bring to justice the invaders in the 1892 Johnson County War, wherein the governor of Wyoming was a secret supporter of big cattlemen. That case never came to trial, as Johnson County prosecutors were unable to seat 12 acceptable jurors.

The men jailed in Big Horn County were personally aware of the unsuccessful prosecution of the perpetrators of a July 1903 raid on the county jail in which two prisoners and a deputy sheriff were killed. That conflict was led by George Saban, the same man who was one of the leaders of the Spring Creek Raid. The 1903 case against him and his confederates had collapsed in an atmosphere of intimidation.

After the Spring Creek Raid, a few Wyoming cattlemen collected a large pool of money to fund the legal expenses of the five defendants. Though there were not many private lawyers in the Big Horn Basin at the time, nearly all were retained by the raiders’ supporters. “Bear” George McClellan and other prominent politicians also supported the raiders, as did area newspapers including the Worland Grit and the Basin Republican. These newspapers harshly criticized virtually every aspect of the prosecution. But things had changed in the Big Horn Basin in just a few short years, and all the attempts to frighten witnesses, intimidate judicial authorities and frustrate the selection of a jury failed.

Large, new irrigation projects around the Big Horn Basin towns of Worland, Powell, Cody and Lovell made farmers—many of them Mormons who had come to Wyoming from Utah and southeastern Idaho in the previous decade—the dominant group in the Big Horn Basin. As farmers, they had no particular sympathies for either cattlemen or sheepmen, and came from what was generally a more peaceable culture. Too, the governor of Wyoming in 1909 was Bryant B. Brooks, a prominent sheepman. His sheep-business sympathies probably added to his willingness to exercise state authority. Brooks was committed to stopping sheep raids; he would not be rendering clandestine assistance to those charged with crime. He ordered the Wyoming militia to guard the streets of Basin City and keep citizens safe.

Contrary to the fervent hopes of the Spring Creek raiders, trials did proceed in November 1909. The first case was brought against Herb Brink. To the surprise of many, the Big Horn County prosecutors had little trouble seating a jury, filling it with farmers who had no stake in the sheep and cattle conflicts. The presence of the militia and numerous law enforcement officers kept Basin City the quiet and peaceable town it usually was. The case, therefore, was decided in the courtroom from evidence presented against Brink, and not in the court of public opinion as had often happened in the past.

State’s evidence was well presented by the attorneys specially hired to assist the prosecution. Those lawyers included two from Sheridan, E. E. Enterline and Will Metz, father of elected Big Horn County Attorney Percy Metz. The prosecution also included W.L. “Billy” Simpson of Cody, Wyo., father of future Wyoming Governor Milward Simpson and grandfather of future Wyoming Senator Al Simpson. Billy Simpson had represented sheep raisers in various cases in the Big Horn Basin before 1909 and thus would have been tainted in the minds of cattlemen, and this was probably the reason they did not hire him.

The state presented photographs and surveyors’ maps to pinpoint the geography and events of April 2, 1909. Eyewitnesses, including sheepherder Bounce Helmer, who had been kidnapped and later released, and three men who watched the raid from an adjacent house all testified. The raiders had made the critical mistake of talking to their acquaintances. Billy Goodrich, whose testimony was secured by LeFors and who was the employer of two of the raiders, told the jury about a series of admissions made by Brink.

The most devastating testimony, however, came from Charlie Ferris and Bill Keyes, two of the original raiders who became state’s witnesses and revealed the inside story. They told how seven men planned a sheep raid, and then rode to Spring Creek from the south during the early evening of April 2, 1909.

Saban and Brink went to a group of wagons, and laid siege to one sheep wagon that had three men inside. The two raiders started firing into the wagon, Brink with a .25-30 Winchester and Saban with a gun referred to in later testimony as a ".35 automatic," most likely a Remington Model 8 rifle chambered in the .35 Remington cartridge. There was silence from the sheep wagon. Brink then pulled some sagebrush, placed it under the wagon and lit it. The fire soon blazed up. Two of the sheepmen were either dead or disabled and did not come out of the wagon. Joe Allemand survived, although apparently wounded. Allemand staggered from the wagon and walked slowly away from it with his hands raised. Brink shot him dead, saying, “It’s a hell of a time of night to come out with your hands up.”

The jury convicted Brink of first-degree murder and sentenced him to hang. After this development, his fellow raiders stampeded to make separate deals with the prosecution. Brink’s death sentence was commuted, but five of the seven Spring Creek raiders were sentenced to serve prison terms. The two who testified for the prosecution were provided immunity.

The convictions from the Spring Creek Raid put a stop to the mayhem committed in Wyoming against sheepmen. After 1909, there were only two minor raids in the entire state, and no one was injured in either. One of the prosecutors, Will Metz, summarized the meaning of the verdicts by saying, “It is significant of the beginning of a new era, of a period where lawlessness in any form will be no more tolerated [in Wyoming] than in the more densely settled communities of the east.”

Resources

- Davis, John W., A Vast Amount of Trouble. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005. The most comprehensive of the books about the Spring Creek Raid. Will Metz’s remark about the end of lawlessness, originally published Nov. 12, 1909 in the Cheyenne State Leader, is on p. 262.

- Gage, Jack. Tensleep and No Rest. Casper, Wyo.: Prairie Publishing Company, 1958. A full treatment of the Spring Creek Raid by then Wyoming Secretary of State Jack Gage. It is beautifully written—but it mixes fact and fiction with no delineation between the two. Still, the book catches the spirit of the event and the complex feelings of many people who were part of it.

- O’Neal, Bill. Cattlemen vs. Sheepherders. Austin, Texas: Eakins Press, 1989. An excellent overview of the sheep and cattle wars within the United States.

- Trenholm, Virginia Cole, ed. Wyoming Blue Book. Vol. III. Department of Commerce, Wyoming State Archives and Historical Department, 1974. Cheyenne. “Cattle and Sheep,” pp. 266-267

Illustrations

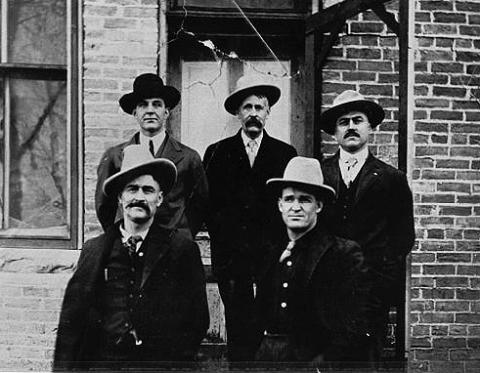

- The photos of the militia in front of the Big Horn County courthouse and the five defendants in the Spring Creek Raid case are from the collections of the Washakie Museum and Cultural Center.

- The photo of the site of the Spring Creek Raid is by Celia A. Davis. All are used with thanks.