- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Still Unsolved: The 1911 Deaths of Edna Richard...

Still Unsolved: The 1911 Deaths of Edna Richards Jenkins and Thomas Jenkins

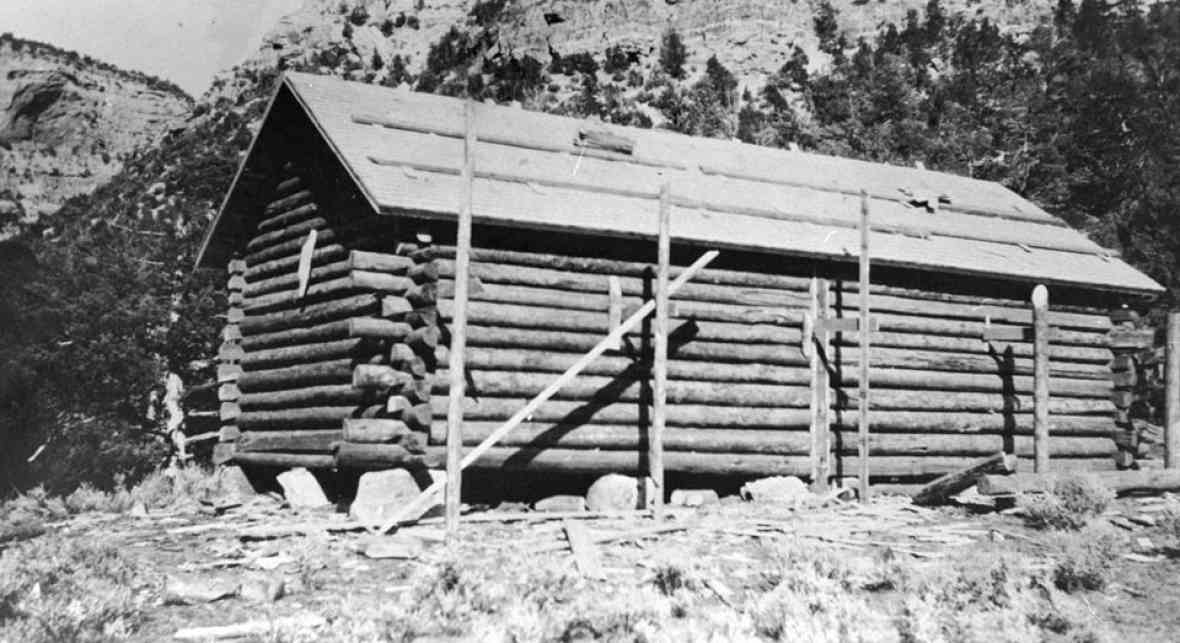

It was Sunday evening, Sept. 24, 1911, and the cabin of former Wyoming Gov. William A. Richards should have been lit and alive with the usual household routines.

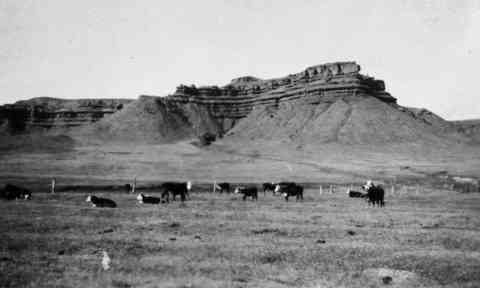

The cabin stood on the Red Bank Ranch on Little Canyon Creek about 20 miles south of Tensleep, Wyo., in what’s now southeast Washakie County. The ranch was owned by the Red Bank Cattle Company, Inc., of which Richards was president. Ranch headquarters lay where the hamlet of Big Trails is now, a few miles upstream from where the creek joins the Nowood River. The cabin was a mile farther up Little Canyon Creek.

That Sunday evening, seventeen-year-old Rhoda Speas and her friend Mary Rebideau, sent on an errand from the main ranch headquarters, were approaching the Canyon House, as the cabin was called. As they drew near, they noticed that the cabin was dark and silent. Riding past the corral and barn, they noticed that a barn door, normally shut, was open. Three horses ran out as the girls passed. In the dim light, Mary thought she glimpsed a man running out behind the horses, but afterward she could never be sure.

Near the house, Rhoda's horse reared, shied and refused to go past a tree, under which a large, unidentified bundle was lying. Mary, whose horse had a calmer temperament, managed to ride around Rhoda, and stopped at the back door of the cabin. Both girls were frequent visitors and Mary, who was thirsty, knew that the drinking water, always fresh and cool, was kept in two buckets on a bench just inside the door. It was too dark to see, but she reached in for a dipperful and found one empty bucket and the other half full of warm, stale water.

Outside, the girls decided to investigate the bundle under the tree, although the light was fading. While Rhoda's horse continued to dance and shy, Mary drew closer to the tree, and then jumped back. Certain that the bundle was a human body, possibly a dead Indian, she remounted her horse, and the girls galloped back to the main headquarters bursting with their disquieting news.

At first, Rhoda and Mary could not convince the men at the ranch that they should investigate, but a few hours later, around 8:30 p.m., a small party rode down to the cabin. The men in the party were Oscar McClellan, owner of a nearby ranch, plus a few other owners of surrounding ranches and some of their employees.

Under the tree, they discovered the body of Edna Richards Jenkins, Richards' 21-year-old daughter. In the house was the body of Thomas Jenkins, Edna's husband of only a little over four months, shot through the heart, lying on a bare mattress on the bedroom floor. Edna had been shot twice through her left chest and once in her left temple. A pistol was found in her left hand and another next to her body.

The case has never been solved. But it remains intriguing to this day, because of the apparent senselessness of the crime, the lack of compelling evidence pointing at any suspect—though three were considered and one arrested—and the social prominence of the victims.

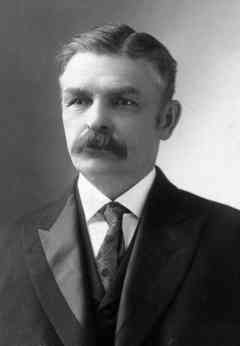

Edna Richards was the youngest of three daughters of Harriet Alice Hunt Richards--called Alice--and William Richards. He was raised in Illinois, and first came to Wyoming Territory from Omaha in the 1870s to assist his brother surveying the southern and western boundaries of the new territory. In 1885 he started the ranch and in 1889 was appointed surveyor general for Wyoming Territory. In 1894, he was elected governor of the new state, served from 1895 to 1899, and may be best remembered as the governor who pardoned Butch Cassidy on a rustling charge. Richards later served as assistant commissioner and then commissioner—chief officer—of the General Land Office, predecessor to today’s U.S. Bureau of Land Management. He returned to Wyoming, and in 1909 took a job as commissioner of taxation for the state. At the time of the murder he was well connected and well known.

Thomas Jenkins, 22 at the time of his death, had been a civil engineer in Ogden, Utah before he married Edna on May 6, 1911. According to Lucia McCreery, great-niece of Edna Jenkins, the wedding was held in Pueblo, Colo., at the home of Alice Richards McCreery, Edna's sister. Afterwards, the couple settled at the Red Bank Ranch to help run daily operations. As far as is known, there were no conflicts between Jenkins and his wife or Jenkins and his father-in-law.

Within days, a coroner’s jury issued a report that the deaths had been the result of a murder-suicide. Two months later, however, after more evidence came to light, the jury issued a second verdict, suggesting that the deaths occurred at the hands of an unknown person or persons. That verdict still stands, although, with the crime still unsolved, the murder-suicide theory persists as well.

Coroner’s jury issues report

The first coroner’s jury convened at the Red Bank Ranch the day after the girls’ discovery, and on Sept. 30, 1911, The Worland Grit published the jury’s verdict. The jury was composed of Oscar McClellan, Charles Wells and James H. Tully. McClellan was the brother of “Bear” George McClellan, treasurer and general manager of the Red Bank Cattle Company, Inc.; Wells was another rancher in the area and Tully was the foreman at the Red Bank Ranch.

The jury’s report stated, “We ... find that the deceased Thomas W. Jenkins came to his death from a pistol shot wound fired by his own hand and that the deceased Edna May Jenkins came to her death from a pistol shot wound fired by her own hand after being shot through the lungs twice by the said Thomas W. Jenkins.”

After Thomas had shot Edna and then himself, the story ran, powder burns had probably set fire to the mattress. Edna had then put out the fire, grabbed the two guns, and gone outside under the tree and shot herself through the head. The presumed cause of these actions was a sudden, violent quarrel. The Cheyenne State Leader even suggested a suicide pact.

Richards, away on a hunting trip in the mountains above Dubois, Wyo., was summoned back immediately. On September 29, The Lander Eagle reported, “A telegram was received in Lander on Monday [September 25] to get Ex-Governor Richards who was on a hunting trip in the Dubois country … E. F. McMasters of the Lander Garage started in an auto after the hunting party … and returned at full speed with … Richards, arriving back in Lander on Tuesday afternoon.”

On returning to the Red Bank Ranch, Richards began his own investigation. In an extensive statement published by The Daily Enterprise in Sheridan on October 2, 10 days or so after the murder, he declared, “I cannot accept the ...verdict. Every circumstance is at variance with premeditation on the part of either Mr. Jenkins or his wife.”

Former Gov. Richards refutes findings

Richards went on to say that he lived at the cabin with the couple and knew their habits. His statement places the likely time of the killings at Friday evening, September 22. Richards described a number of chores that had obviously been done: the clean laundry, sprinkled, rolled up and still damp in the basket, awaiting Saturday's ironing; the bread, baked once a week, sitting out to cool as usual for a Friday afternoon; the table, set for next morning’s breakfast after the dishes had been washed after supper; trout cleaned for breakfast, sitting on the table ready to cook, “even to being sprinkled with flour.” The horses and milk cows had also been fed.

“An affair of this kind cannot take place without a cause,” Richards concluded, “and there was absolutely no cause ... for suicide or any trouble between them.” Letters from Edna Jenkins, now at the Washakie Museum in Worland, Wyo., appear to corroborate this. On August 30, she had written to Thomas, who had just left for Omaha, Neb., with some cattle, and also to visit the eye doctor. He returned by the middle of September. On September 16 she wrote to her father, who had then been on his hunting trip for almost two weeks. Both letters were happy and affectionate in tone.

Other circumstances, mostly discovered by Richards, added to the possibility that a third person had been present: missing cash and jewelry, that open barn door, noticed by the girls, that should have been closed—and more bullet holes. Two were found in the bedroom walls, and three more in the living room. One of them pierced a portrait of Richards.

Coroner’s jury revises verdict

Based on these and further findings, the jury issued a revised verdict, published by The Worland Grit on December 7, more than two months after the crime: “[B]y reason of new evidence not before us at the inquest ... [of] September 25th, 1911, it is now our opinion that the [victims] died ... at the hands of some person or persons ... unknown.” This verdict, unlike the first, mentions the name of the coroner, Dr. C. Dana Carter.

This new evidence, though not specified in the published verdict, almost certainly included the bullet holes found in the walls as well as the fact that Edna was right-handed. Richards revealed this information in a November 30 letter to his friend Willis Van Devanter, a longtime Wyoming attorney who had recently been named as a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. Richards and Van Devanter exchanged several letters during Richards's investigation, weighing the evidence and comparing their impressions. “Edna's right shoulder bore the imprint of a heavy left hand, the thumb in front, the four fingers behind, all plainly visible, while the bone above her left eye was broken and indented by a blow from a smooth object or instrument which did not break the skin,” Richards wrote.

Also, when found, Edna was wearing her nightgown with her bathrobe over it. There were two bullet holes in her gown, but none in her robe. In addition, her legs were freshly cut and scratched and had been bleeding, and the ball of one toe was torn off. Over her legs she wore knee-length bed stockings, undamaged. Most telling of all, under the tree where Edna lay, no blood was found, even after a thorough search. This information was apparently not published in the press reports at the time. It was probably part of Richards's discoveries, and “wasn't revealed all at once,” states former Worland Police Chief Ray Pendergraft, in an undated transcript of a tape recording that was clearly made on a tour of the crime site at least 50 years after the event. Pendergraft also notes similar details about the state of Edna's body in his account of the crime in Washakie: A Wyoming County History.

“[T]he carpet underneath the bed [as well as the mattress on the floor] was saturated with water,” Richards observed in his October 2 statement. “It seems impossible that a girl with two bullets through her lungs could have done this ... There was no blood in the kitchen, although the water bucket had been returned to its proper place.” It is unclear whether this is one of the two drinking water buckets mentioned earlier.

“I think they were afraid of something,” Richards wrote to his daughter Ruth in California on October 26. “[M]y three large revolvers were loaded, while before I went away I took the cartridges out of all of them.” Also, in his November 30 letter to Van Devanter, he observed, “That they were afraid of somebody is shown by their sleeping upon a bed upon the floor, under a window beside the bed upon which they usually slept.” This slight but noticeable discrepancy in detail is an example of the contradictions that crop up throughout the sources in this case. Was the mattress indeed bare, as some accounts state, or was it made up for sleeping on, as Richards implies here?

Suspects investigated and released

Newspaper subscription salesman and reporter Edward T. Payton, his name often misspelled in newspaper reports as “Peyton,” was the only person ever arrested for this crime. Payton was subject to fits of mental illness and had been hospitalized four times at the state mental hospital in Evanston, Wyo., then called the Wyoming Hospital for the Insane.

In addition to his mental problems, Payton was a known adversary and critic of Richards, having attacked him in print years before during the 1894 gubernatorial campaign, alleging that Richards made fraudulent land deals—though apparently no criminal charges were ever brought against Richards.

Near the beginning of October, The Wyoming Tribune reported that Payton “showed up in the vicinity of … [the ranch] and was so clearly out of his head and caused so much trouble that the sheriff was notified … While in this condition, Peyton is said to have constantly muttered about the dead woman and to have made other remarks which aroused suspicion.”

On October 6, a Big Horn County sheriff's deputy arrested Payton and he was held in the county jail in Basin, Wyo. (Washakie County was then part of the much larger, original Big Horn County.) There was no material evidence against Payton, however, and Oscar McClellan claimed he could “account for every minute of [Payton's] time” when at or near the ranch. Payton was never charged, and was released on or about October 20.

Two other men were briefly suspected, O.K. Fullerton and Tom O'Day. Fullerton, nicknamed Packrat Murphy, was an odd-jobs man around the ranch. According to local lore, he had been attracted to Edna and was reportedly known to be a thief in the area. O'Day was a former member of the Hole in the Wall Gang and had served a prison term for horse theft. An old trail ran by the Richards cabin, “[A] route formerly travelled [sic] by bad men going from Thermopolis ... to the Hole in the Wall,” wrote Richards to Van Devanter. This fact, plus O'Day's presence on or near the ranch around the time of the murder, put him briefly under suspicion. However, there was no hard evidence against either O'Day or Fullerton.

The story continues

Oscar McClellan passed down a story to his son, Howard, who retold it within the last decade to his acquaintance John W. Davis, a Worland lawyer and historian: “[Oscar] said that he and the other two jury members scoured the area ... for footprints or any other sign of another human being, but found nothing,” Davis recalls.

This apparent lack of footprints is nearly the only credible evidence that points to murder-suicide. On October 11, almost two months before the second coroner's verdict was published, Van Devanter wrote in response to a letter he'd received from Richards on October 6, “I shall entertain a very strong belief that a third person was present and took the lives of both Mr. and Mrs. Jenkins. Every single thing which I have heard can be … readily reconciled with that theory.” John Davis observes that the circumstances “just scream … out” that a third person had to have been there.

Pendergraft puts it even more forcefully at the end of the interview transcript: “[D]efinitely it was not murder and suicide—could not have been.”

The case for double murder is strong to the point of being nearly irrefutable. Dead bodies don't bleed. Since no blood was found under the tree, Pendergraft notes, Edna Jenkins was probably dead when placed under it. Thomas Jenkins could not have shot her and then shot himself, because, according to all accounts, no gun was found near his body.

The circumstantial evidence, as Richards noted, points to the usual household routine, smoothly followed—up to the point when the violence began. After that, huge questions remain, the largest being, what actually happened? What logic could connect all the detail? Who put Edna's robe on her after she had been shot? People with chest wounds die quickly; would she have had time to put on her robe, much less to do the other things attributed to her? As for the gun in her left hand, how likely is it that she would have used her non-dominant hand under such severe duress? How did the mattress catch fire? How was it doused? What explains the bullet holes in the wall? In the portrait? Who was the man, if indeed he was there, that Mary Rebideau thought she might have seen running out of the barn?

Immediately after the crime, at least 15 newspapers reported the discovery of the bodies, often including the suicide theory. After the early October reports of Payton's arrest and the revised coroner's jury report published on December 7, coverage seems to have died out. However, up to the present day in Washakie County, John Davis observes, the subject has “occasioned much discussion … and everyone has their opinions.”

The Jenkins murders took place only two and a half years after the April 2, 1909 Spring Creek Raid south of Tensleep, when seven cattlemen murdered three sheepmen. Five of the cowboys were later caught and sentenced to prison. Prior to that time, lawlessness had reigned, and criminals often went unpunished or were lynched. By 1911, the legal process had developed and civil authority had strengthened—but not enough to solve the two murders on Canyon Creek.

In April 1912, on invitation by former Wyoming State Engineer Elwood Mead, Richards traveled to Australia to investigate farming and ranching possibilities. He died of a heart attack in Melbourne on July 26 of that year. Did the shock and grief of his daughter's death kill him? This, like so many other questions relating to the tragedy, will never be answered.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “Coroner's Jury Revises Verdict in Jenkins' Case,” The Worland Grit, Dec. 7, 1911, 1. Accessed May 6, 2015, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Davis, John W., Worland criminal attorney and Big Horn Basin historian. Personal emails to the author. April 28, 2015.

- “Did Peyton Murder the Jenkins Couple?” Cheyenne State Leader, Oct. 7, 1911, 1. Accessed May 6, 2015, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- “E.T. Payton Suspected of the Jenkins Murder,” The Wyoming Tribune, Oct. 7, 1911, 1-2. Accessed May 6, 2015, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- “Ex-Gov. Richards Cannot Accept Suicide Theory,” The [Sheridan] Daily Enterprise, Oct. 2, 1911, 1. Accessed May 6, 2015, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Frison, Paul. “Lest We Forget,” 1978. W. A. Richards Collection, Box 6, H82-61. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- “Great Mystery in Red Bank Tragedy,” Cheyenne State Leader, Sept. 25, 1911, 1. Accessed May 6, 2015, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Jenkins, Edna to Thomas Jenkins, Aug. 30, 1911. Washakie Museum and Cultural Center, Worland, Wyo.

- Jenkins, Edna to William A. Richards, Sept. 16, 1911. Washakie Museum and Cultural Center, Worland, Wyo.

- McCreery, Lucia, great-niece of Edna Jenkins. Telephone interview with the author. May 5, 2015. Personal emails to the author May 5 and 6 and June 16, 2015. Information used with special thanks.

- Pendergraft, Ray. Untitled Oral History. Irma E. Mueller Collection, H81-24. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo. This manuscript, obviously a transcript of a tape recording, is undated and no author or speaker is named. However, the internal evidence makes it clear that the speaker is Ray Pendergraft, chief of police in Worland for a number of years beginning in 1948. The person on the tape says he was a chief of police in Worland, clearly knows the circumstances of the crime, plus the oral history closely matches Pendergraft's account in his Washakie County History (see citation, below.)

- Richards, William A. to Ruth Richards Barrett, Oct. 26, 1911. Alice McCreery Collection, Box 2, H63-86. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- Richards, William A. to Willis Van Devanter, Nov. 30, 1911. Washakie Museum and Cultural Center, Worland, Wyo. Also available at Library of Congress: Willis Van Devanter Papers, Box 29, Folder 3.

- Stottler, Robert, curator, Washakie Museum. Telephone interview with author. May 8, 2015.

- “Terrible Tragedy Occurs At Red Bank,” The Worland Grit, Sept. 30, 1911, 1. Accessed May 6, 2015, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- “Tom O’Day Released.” The Basin Republican, June 19, 1908. Accessed June 5, 2015 at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- “Two Dead in Suicide Pact,” The Lander Eagle, Sept. 29, 1911, 1. Accessed June 6, 2015, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Van Devanter, Willis to William A. Richards, Oct. 11, 1911. Alice McCreery Collection, Box 2, H63-86. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- Wyoming, State of, Executive Department. Pardon issued to George Cassidy for Grand Larceny. Jan. 20, 1896. Signed by William A. Richards, Governor. Record of Pardons, Vol. 1, p. 86. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

Secondary Sources

- Davis, John. “The Spring Creek Raid: The Last Murderous Sheep Raid in the Big Horn Basin.” Accessed June 8, 2015, at /essays/spring-creek-raid.

- Ewig, Rick. “E. T. Payton: Savior or Madman?” Annals of Wyoming, 79: 1, Winter 2007, 18-36.

- Hein, Annette. “Washakie County, Wyoming.” Accessed June 8, 2015, at /encyclopedia/washakie-county-wyoming.

- “List of Commissioners of the General Land Office.” Wikipedia, accessed June 5, 2015 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Commissioners_of_the_General_Land_Office.

- Pendergraft, Ray. Washakie: A Wyoming County History. Basin, Wyo.: Saddlebag Books, 1985, 126-131.

- “William A. Richards.” Wikipedia, accessed June 9, 2015 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_A._Richards.

Illustrations

- The 1910 photos of the cabin under construction are from the collection of the Washakie Museum and Cultural Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of Edna Richards as a teenage girl, of William Richards and of the scene on the Red Bank Ranch are from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.