- Home

- Encyclopedia

- President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1903 Visit To Wy...

President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1903 Visit to Wyoming

In April and May of 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt visited Wyoming, speaking at Yellowstone National Park and the towns of Newcastle, Evanston, Laramie and Cheyenne as part of his eight-week, 25-state tour. His route, like a 14,000-mile lasso flung to rope the whole American West, snagged points as far north as Fargo, N.D., and as far south as Los Angeles.

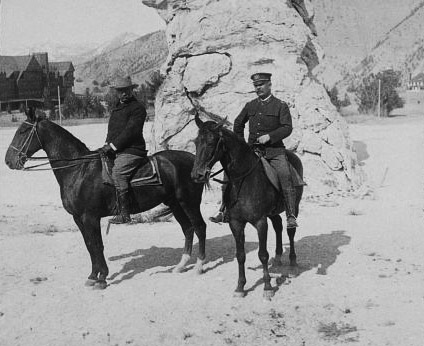

Roosevelt gave a total of 263 speeches, seven or eight per day on average, in his five and a half weeks of public appearances. The balance of the time he spent camping in back country: two days at Yosemite with conservation activist John Muir, and 16 days, April 8-24, in Yellowstone. There he was accompanied by wildlife writer John Burroughs, Park Superintendent Major John Pitcher and a small mounted escort. The press was left behind in Gardiner, Mont.

While in the park, on April 16, Roosevelt wrote a detailed letter to Dr. C. Hart Merriam, a physician and early conservationist who had been head of the Section of Economic Ornithology in the Department of Agriculture and its successor agencies since 1885. Roosevelt reported on the numbers, habits and condition of game in Yellowstone, noting that “coyotes wander about among…sleeping or feeding elk without attracting any attention whatever." He witnessed the attempt of a golden eagle to cut a yearling elk calf out of a herd and commented, "The elk far out-number all the other animals," estimating at least 15,000 within the park. He also mentioned that "around the hot springs the cougars are killing deer, antelope, and sheep…"

On April 24, Roosevelt dedicated a new arched gateway to the park with a short speech. Then he boarded his train, bound east for Omaha. Newcastle, Wyo. was one of many whistle stops the next day.

Sometimes Roosevelt made his speeches from the rear platform of the Elysian, his 70-foot long railroad car; at other times he made them from a decorated platform at the nearby depot. In Newcastle, as with many other stops, his path from train to platform was strewn with flowers. According to the April 26, 1903 edition of the Wyoming Tribune, the platform itself was decorated with three statues: a deer, a bear and an eagle.

The Tribune paraphrased his half-hour speech about resource development and good citizenship. These, along with conservation, were his three main themes, reiterated throughout his western tour. The "new irrigation law,"—the Reclamation Act of 1902—the president said, was especially important to the West. Under this law, such water users as farmers, ranchers and other settlers would help to pay construction costs of irrigation projects in exchange for the benefits they received.

Roosevelt's and many others’ dream was that large tracts of dry land could be irrigated and thus made arable, supporting vast numbers of people. Noting that government could undertake experiments and large projects that private citizens could not, he added that, even if they didn’t help plan and execute the projects, the people could still benefit and learn from them.

From Omaha, Roosevelt’s tour looped west again, traveling via Santa Fe to Los Angeles, Yosemite, San Francisco and Seattle. In late May, he was headed east from Salt Lake City. He stopped for 20 minutes in Evanston on the evening of May 29, 1903. The May 30 issue of the Cheyenne Daily Leader estimated the Evanston crowd at 7,000, gathered from throughout Wyoming as well as the surrounding states of Utah, Idaho and Colorado.

The following day Roosevelt stopped in Laramie at 7:30 a.m. for about 90 minutes, speaking at the university to a crowd estimated between three and four thousand, including children and college students.

According to the Leader, he remarked, "A stream cannot rise higher than its source and the government cannot be greater than average [sic] of its citizenship." This theme, along with extensive references to the Civil War and the Spanish-American War, dominated his remarks for the rest of the Decoration Day (now called Memorial Day) weekend.

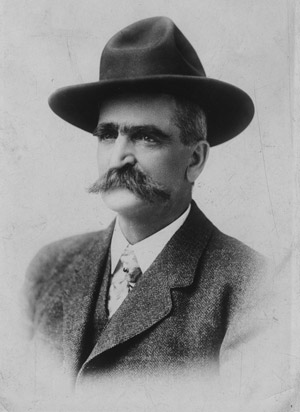

Next, by prior arrangement, the president rode horseback 65 miles from Laramie to Cheyenne. Changing mounts three times, for a total of four horses ridden, Roosevelt was accompanied by 10 prominent citizens, including Sen. Francis E. Warren, U.S. Marshal Frank Hadsell, Deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors, Albany County Sheriff N.K. Boswell of Laramie, local stockman R. S. Van Tassell, and Black Hills Forest Reserve Supervisor and former Deadwood, S. D. lawman Seth Bullock.

The Leader lavished nearly 1,000 words of copy on this phase of Roosevelt's visit to southeast Wyoming, including the entire text of a speech by Warren. The senator presented the president with a saddle, matching bridle and blanket that he described minutely, saying it was from "Your friends in Cheyenne…"

The Leader went on to detail the name of each horse the president rode, its physical prowess, temperament and other virtues; inevitably, one was named Teddy. The Leader also listed the owners: Ora Haley, Johnny Earnest and Van Tassell, who contributed two of his horses. Haley declared that after Roosevelt rode his horse, Yellowbird, nobody else would ever ride him again.

The party ate lunch at the Van Tassell ranch and arrived in Cheyenne at 4:00 p.m. A lengthy procession and parade brought Roosevelt to a speaker's stand at 15th and Ferguson (now Carey Avenue). At 7:00 p.m., he spoke to a crowd of approximately 10,000. His speech was extensively quoted in the June 1 Cheyenne Daily Leader. As he had in Laramie, he focused on good citizenship and the parallels between military and civilian life.

Emphasizing the importance of hard work and solidarity, he declared that in war, so long as a soldier’s comrades stand with him, “ … you don’t care where that man’s birth place has been; you don't care a snap of your fingers [how]…he worshiped his Maker; you don't care…whether he was a banker, bricklayer, lawyer, mechanic or farmer…It is the same thing now in civil life." Roosevelt also briefly mentioned his support for the Monroe Doctrine and the importance of a strong, efficient navy, with a special mention to the battleship USS Wyoming.

Roosevelt stayed in Cheyenne two more days. He attended church on Sunday morning, May 31, and lunched with former U.S. Sen. and future Gov. Joseph Carey and his wife. On Monday, the president attended a wild west show presented in his honor and later that day rode horseback to an evening barbeque at the Warren ranch. On Tuesday he boarded his train and three days later was back in Washington D.C.

Clearly, Roosevelt loved the American West. His enjoyment of wildlife, scenery, camping and horseback riding practically ensured that he would spend more than a quarter of his eight-week tour in Wyoming. He stayed in the state a total of 19 days—most of them in Yellowstone and three in Laramie and Cheyenne.

Biographer Edmund Morris, in Theodore Rex, notes Roosevelt's reverence for nature, exemplified in his extreme displeasure when confronted near Santa Cruz, California, with an ancient redwood decorated with "a petticoat of calling cards and advertising posters." Morris also reports that in his first year as president, Roosevelt had "quietly" increased the federal forest reserves by a full third.

Wyoming benefited not only from Roosevelt's appreciation of natural wonders like Yellowstone, but also from federal funds from the Reclamation Act. According to Morris, America's heartland was Roosevelt's "political center of gravity."

Roosevelt could have spent two weeks in Yosemite and two days in Yellowstone instead of the opposite. He also took the time to socialize with Sens. Warren and Carey and the people of Cheyenne rather than treating the capital city as just another whistle stop. The choice suggests that he felt a special tie to Wyoming, whether emotional, social, political or all three.

Resources

Primary Sources

- "A Hard Day: President Roosevelt Spoke to the People of Three States in 12 Hours," The Wyoming Tribune, April 26, 1903, 1. Accessed Jan. 19, 2013 at http://www.wyonewspapers.org.

- "At Evanston: President Delivers Address from Platform Near Depot to Crowd of 7,000 People," The Cheyenne Daily Leader, May 30, 1903, 1. Accessed Jan. 26, 2013, at http://www.wyonewspapers.org.

- "At Laramie." The Cheyenne Daily Leader, May 30, 1903, 1, 4. Accessed Jan. 26, 2013, at http://www.wyonewspapers.org.

- "Roosevelt's Enthusiastic Reception: Triumphant Entry into Cheyenne After Thrilling Ride Over the Continental Divide." Cheyenne Daily Leader, June 1, 1903, 1, 3. Accessed Jan. 26, 2013, via http://www.wyonewspapers.org.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Letter to C. Hart Merriam. April 16, 1903. Theodore Roosevelt Center, Dickinson State University, Dickinson, N.D. Accessed January 23, 2013, at www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org.

- “The Cross Country Ride To Cheyenne.” Wyoming Tribune, May 31, 1903, 4, accessed March 6, 2013 via http://www.wyonewspapers.org. Pages are misnumbered in this database; to read page 4 of the May 31, 1903 edtion, click on the listing for page 6 of the same date.

- U.S. Geological Survey. “Sherman Quadrangle.” 1:125,000 contour map, 1903 survey, edition of 1905. Accessed March 6, 2013 at http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/topo/wyoming/txu-pclmaps-topo-wy-sherman-1903.jpg

- U.S. Geolgocial Survey. “Cheyenne Quadrangle.” 1:125,000 contour map, 1911 survey, edition of 1914. Accessed March 6, 2013 at http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/topo/wyoming/txu-pclmaps-topo-wy-cheyenne-1911.jpg

Secondary Sources

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex. New York: Random House, 2001, 214-235.

- Roberts, Phil. "Teddy Roosevelt's Ride: The President's Trip to Wyoming in 1903." Weston County Gazette, April 12, 2007, 12. Accessed Jan. 21, 2013, at http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2162&dat=20070412&id=UsIyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Ww8GAAAAIBAJ&pg=2148,1019003.

- United States Bureau of Reclamation. "The Bureau of Reclamation: A Very Brief History." Accessed Jan. 21, 2013, at http://www.usbr.gov/history/borhist.html.

For Further Reading

Theodore Roosevelt’s good friend, former Deadwood, S.D. lawman, Rough Riders officer, and later U.S. Marshal Seth Bullock, has reached a new level of fame in recent years thanks to the 2004-2006 HBO TV series “Deadwood,” in which a sympathetic Bullock, portrayed by actor Timothy Olyphant, is one of the central characters.

Shortly after the president left Yellowstone in April 1903, Bullock met him in Butte, Mont. for what turned out to be a rowdy banquet there, according to Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris. Roosevelt’s invitation to Bullock to join him for the event, and a number of other letters from their long correspondence at the online archives at the www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org, give a clear sense of their friendship.

See the Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Seth Bullock. April 27, 1903. Theodore Roosevelt Papers, Manuscripts division. The Library of Congress. Accessed March 4, 2013 at http://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record.aspx?libID=o184796, Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

Illustrations

- The 1903 photos of Theodore Roosevelt at Liberty Cap in Yellowstone, giving a speech in Newcastle, and on the famous ride from Laramie to Cheyenne are all from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Seth Bullock is from the Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site, accessed via the Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library at Dickinson State University. Used with thanks.