- Home

- Encyclopedia

- A Stuntman’s Jump: Parachutist Stranded For Day...

A Stuntman’s Jump: Parachutist Stranded for Days on Devils Tower

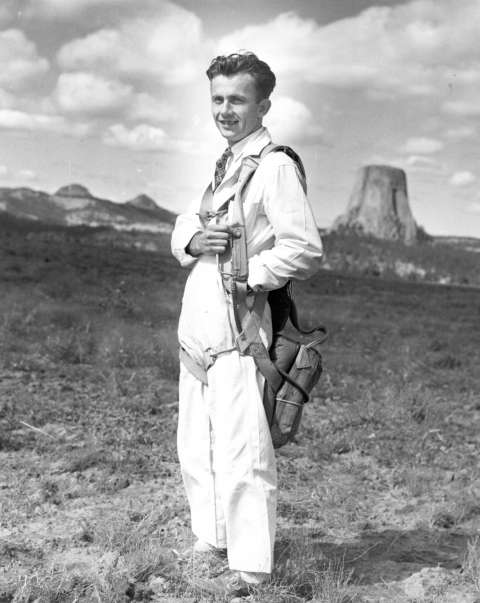

In October 1941, when Hitler ruled nearly all of Europe and Pearl Harbor was still two months away, heads turned from a raging World War to Wyoming. A 29-year-old daredevil, George Hopkins, parachuted onto Devils Tower––the nation’s first national monument––and remained there for six days of increasing press and radio pressure while officials figured out what to do.

According to Mary Alice Gunderson’s 1988 book, Devils Tower: Stories in Stone, Hopkins planned the parachute stunt to win a $50 bet. This wasn’t the full story, however. He wanted to set the world record for the number of parachute jumps in a day–– 30 at the time—and chose Rapid City, S.D., as the site to do so. To gain publicity for the event, Hopkins decided a single jump would suffice, says the National Park Service. He wanted to prove that a parachutist could land on a small target.

At the time, Hopkins held several U.S. records, including the most parachute jumps (2,347) and jumping from the greatest height (26,400 feet).

The Rapid City Chamber of Commerce also sponsored an airshow, with the stunt of parachuting onto Devils Tower as the “perfect” way to publicize the show, writes Gunderson. The proceeds were to fund general hospital construction in the city.

Although Hopkins had planned—on paper—his descent off of the tower, the situation quickly became rocky when South Dakota pilot Joe Quinn returned an hour after the jump to deliver ropes and climbing equipment to Hopkins. The bundle bounced off, fell fifty feet down from Hopkins and snagged on bushes on the tower’s sides. Quinn flew back to Rapid City and couldn’t be reached. Pilot Clyde Ice delivered a second rope, but Hopkins soon concluded that it was too tangled for his descent. He would have to stay the night.

After Hopkins spent the night shivering in the rain, more than a thousand spectators, photographers, and newspaper reporters flocked to the scene. Park Service officials sent rangers and climbing guides to Hopkins’s aid with rescue equipment. Hopkins hoped to parachute to the ground. But a note from Earl Brockelsby, who had bet Hopkins the $50, reached him as Ice removed the doors of his plane and prepared to drop more food: The idea was vetoed.

While Hopkins was dropped more supplies, no plan of descent had been fully decided upon. Park officials decided to enlist the help of Ernest K. Field, a ranger from Rocky Mountain National Park, and Warren Gorrell, a licensed climbing guide from Colorado.

He stayed atop the tower for another night, sharing food with chipmunks and squirrels, says Gunderson’s book. While the third day on the tower was uneventful for Hopkins, crowds continued to increase and national newspapers featured them, buzzing about the story of “Devils Tower George.”

According to Jeanne Rogers’s 2008 book, Standing Witness: Devils Tower National Monument, a History, the stunt was completed without the approval of the National Park Service. Regional Coordinator of the NPS at the time, Edmund Rodgers, stated, “This is the kind of stunt we are not sympathetic with. We of the park service hate to jeopardize our men’s lives for a stunt somebody thought was smart.”

The group of officials, including Brockelsby, worked on more rescue possibilities, from a team of climbers to guide Hopkins down the tower to using the Goodyear Blimp. The blimp, however, could be used only if it would survive the rescue. This was uncertain, so Goodyear rescinded the offer. Even the Navy offered a helicopter to save Hopkins.

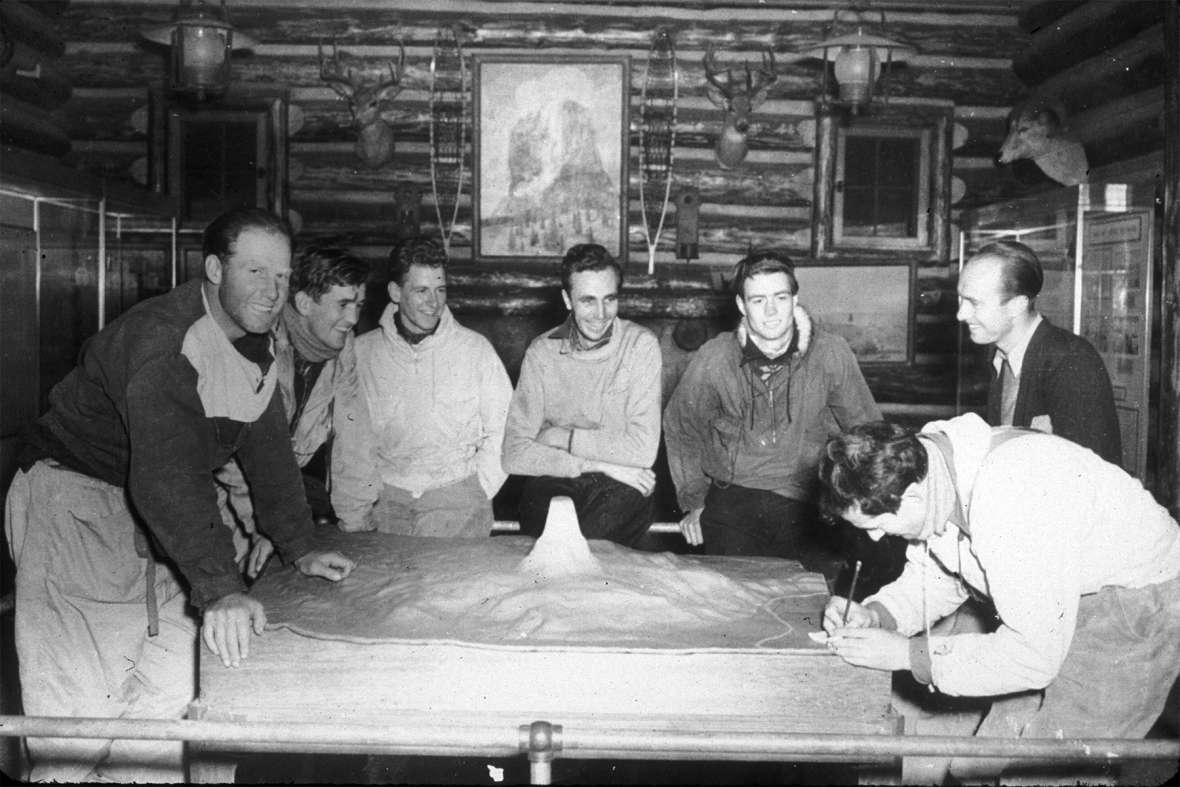

A rescue climb seemed the best way to go. Dartmouth College student and experienced climber Jack Durrance led the rescue mission, along with aid from Field and Gorrell. In the late 1930s, Durrance had pioneered climbing routes up Devils Tower and several in the Tetons. In 1939 he was part of a party that tried to climb K2 in the Himalayas, the world’s second highest mountain. During the crisis with Hopkins, Durrance sent a wire to volunteer himself to help aid the mission if needed.

Once summoned, Durrance and fellow Dartmouth student Merrill McLane made it to the tower on October 5th at midnight and began the rescue the next day, the sixth since the stunt.

“It’s not easy but can be done,” Durrance said in an Associated Press article, which ran in papers nationwide.

Durrance led a team up the tower at 7:30 a.m. and despite the cold, damp weather, after a few hours all eight climbers were on top of the tower enjoying lunch with Hopkins.

Rogers included an account of the rescue from Field in her book: “Hopkins, of course, was glad to see us. He seemed entirely nonchalant and not a bit worse for wear.” Field this was because of the amount of supplies dropped to Hopkins to make his days on the tower comfortable. So comfortable that it was reported that “the parachutist had settled down with a bottle of whiskey to await rescuers.” Hopkins had “requested and received” the drink “for medicinal purposes,” according to an Associated Press story which ran in the New York Daily News.

The descent from the tower began at 4:45 p.m. All climbers reached the base by 8:20 p.m. with reporters anxiously waiting to interview Hopkins. During the six days, an estimated 7,000 visitors came to see the spectacle.

“This started out as a publicity stunt, but it backfired, then wildfired,” said Brockelsby.

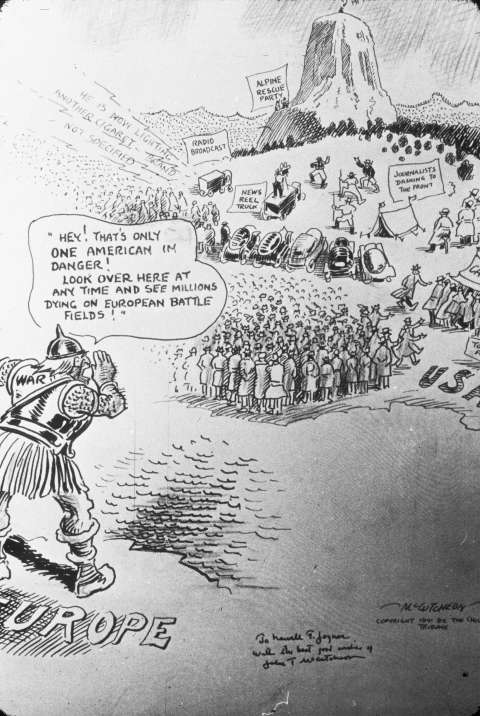

In addition to newspaper reports, many papers ran political cartoons featuring the incident. The Chicago Tribune, for example,published a cartoon that portrayed Europe’s frustration with Americans. An armored figure labeled “War” yells across the Atlantic at a crowd gawking up at Devils Tower: “Hey! That’s only one American in danger! Look over here and see millions dying on European battlefields!”

At the time, Nazi Germany and its ally, Italy, had conquered nearly all of Europe. Only Great Britain resisted. The United States would not enter the war until two months later, when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

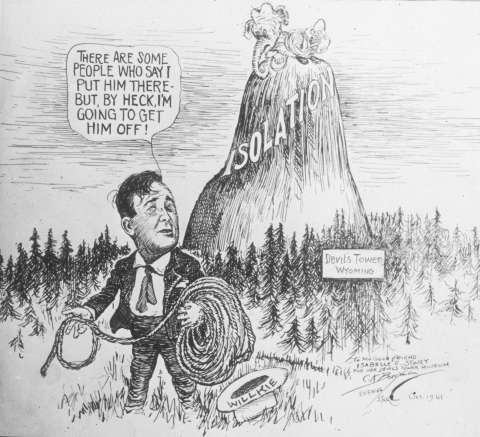

The cartoons took on domestic politics as well—but they were a domestic politics consumed by the war. Chicago’s Evening Star published an image showing former presidential candidate Wendell Willkie attempting to lasso an elephant (representing the Republican Party) stranded on top of a Devils Tower labeled “Isolation.” Willkie had won the Republican nomination for president in 1940 over strongly isolationist candidates opposed to U.S. entry into the war. He lost the election to Franklin Roosevelt, but at the time of Hopkins’s stunt, remained the most prominent Republican in the nation—and was maintaining a high public profile advocating for U.S. aid to Britain.

As for Hopkins, he enlisted in the army once the war began. He helped train paratroopers and supervised the making of drops behind enemy lines. He also staged airshows for charity.

According to Rogers, Hopkins quit “flying and jumping” in 1958. He said that during an airshow in Mexico, “I suddenly asked myself what I was doing there. … I just landed and walked away, and I haven’t been up since.”

The June 4, 1972, Casper Star-Tribune reflected, “If the illegal stunt were to happen today, the rescue would be swift. Army helicopters have hovered over the tower (official permission was obtained beforehand) and climbers now climb the tower in about four hours.”

The article also noted that the Park Service’s prime concern was that others may try stunts similar to Hopkins’s but “everyone seemed to respect the Tower too much to give a repeat performance.”

Resources

Primary Sources

- "Blimp to Try Tower Rescue; Climbers Fail." [New York]Daily News, October 5, 1941, accessed May 31, 2019 via Newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/432738354/?terms=%22Blimp%2Bto%2BTry%2BTower%2BRescue%3B%2BClimbers%2BFail%2BAND%2B%5BNew%2BYork%5D%2BDaily%2BNews%2C.

Secondary Sources

- Bernd, Harold. "Parachutist Stranded Six Days in Devils Tower Saga of 1941." Casper Star-Tribune, June 4, 1972, accessed May 31, 2019 via Newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/446114209/?terms=Parachutist%2BStranded%2BSix%2BDays%2Bin%2BDevils%2BTower%2BSaga%2Bof.

- Gunderson, Mary Alice. Devils Tower: Stories in Stone. Glendo, Wyo.: High Plains Press, 1988, 110-120.

- “Parachutist George Hopkins." National Park Service, accessed July 07, 2019 at https://www.nps.gov/deto/learn/historyculture/first-fifty-years-george-hopkins.htm.

- Rogers, Jeanne. Standing Witness: Devils Tower National Monument—a History. [Devils Tower, Wyo.]:Devils Tower Natural History Association, National Park Service, 2009, 117-126.

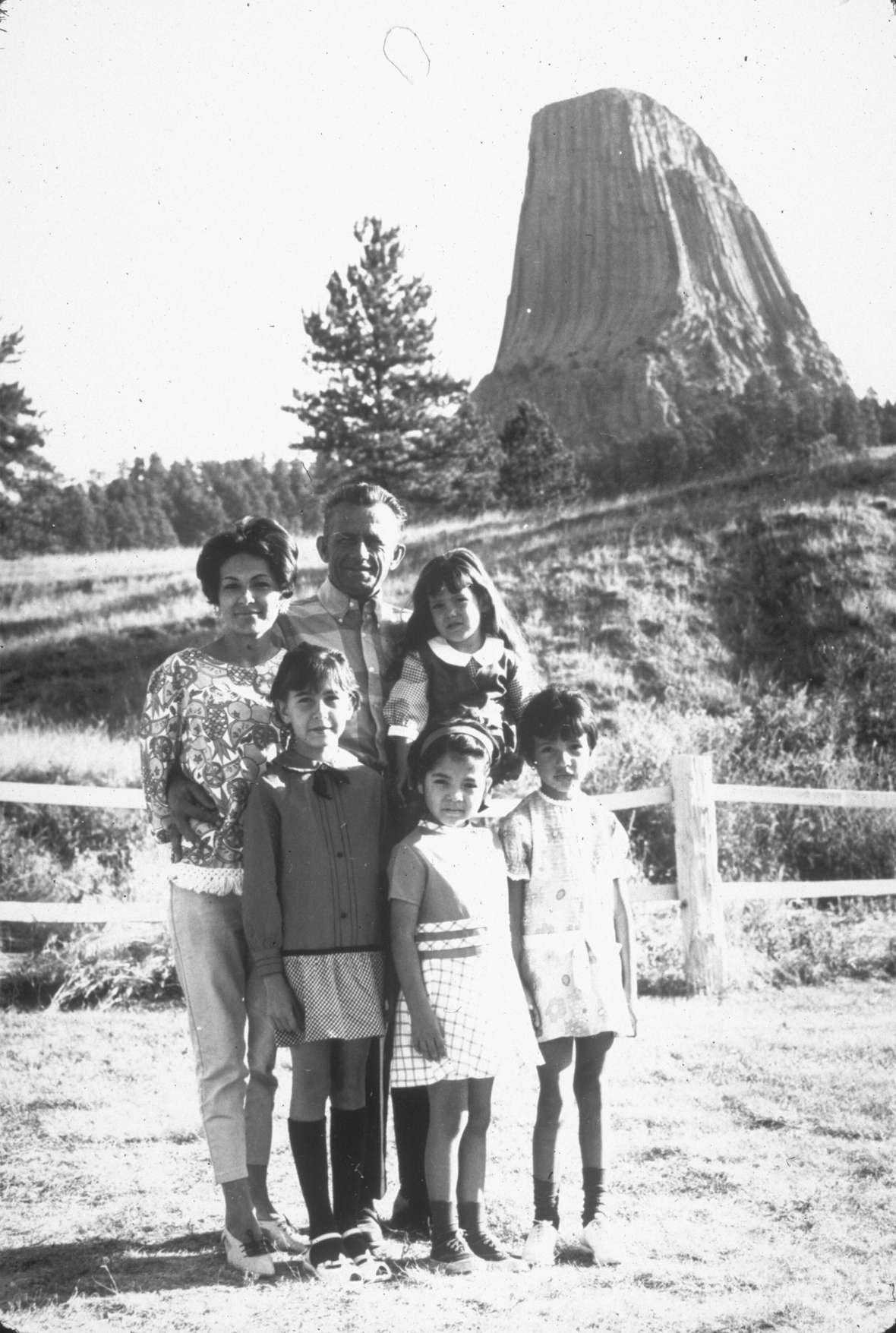

Illustrations

- The photos and the two cartoons from a gallery of images of and about George Hopkins on the National Parks Service’s Devils Tower website. Used with thanks.