- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Life On The Home Front: Wyoming During World War I

Life on the Home Front: Wyoming During World War I

In late November 1917, seven months after the United States entered World War I, a high school teacher in Powell, Wyo., was asked to resign because she was a pacifist. The Nov. 22, 1917, Powell Leader reported that members of the community had been complaining to the school board that Miss Georgiana Youngs had been making "unpatriotic expressions" in the classroom. The article did not identify those who complained.

Youngs "felt she could not refrain from expressing her views on the subject of war when the question came up," so the board decided that "the best interests of the school would be conserved if she resigned, which she did." Although The Leader noted, "[n]o charge of disloyalty or un-Americanism is held against the teacher," the message was clear: In the patriotic fervor sweeping Wyoming and the nation in wartime, dissenting views were not tolerated.

Prelude to war

From Aug. 3, 1914, when German forces invaded Belgium and declared war on France, until April 6, 1917, when President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany, the prevailing attitude in Wyoming and the United States was neutral and isolationist. The majority of citizens apparently felt that since the United States was not seriously threatened, the nation should stay out of the conflict.

Still, war news flooded the country. Wyoming citizens participated in relief efforts, especially for Belgium. In the "flour relief program," from November 1914 to January 1915, residents of the state donated money to purchase flour from local mills to be shipped to starving Belgian women and children. Cheyenne and Laramie, Wyo., together provided 32 tons of flour.

The Red Cross also was active. The Wyoming Tribune in Cheyenne reported Nov. 25, 1914 that "ragged little waifs contributed their pennies” at a fundraiser and “wore a Red Cross bedecked pin with as great a pride as the plutocrat who gave his greenbacks." By noon, “eager girls and their chaperones, stationed all over the city”, had collected $400.

Many citizens followed war news with interest. On Aug. 29, 1914, The Wyoming Tribune mentioned a "long and ardent discussion of the European war" at the recent meeting of the Young Men's Literary Club in Cheyenne. About a year later, two men were arrested after a fist-and-knife fight in Sheridan, Wyo., over which side would win the war.

On Feb. 14, 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act to allow for prosecution of spies.

Wyoming at war

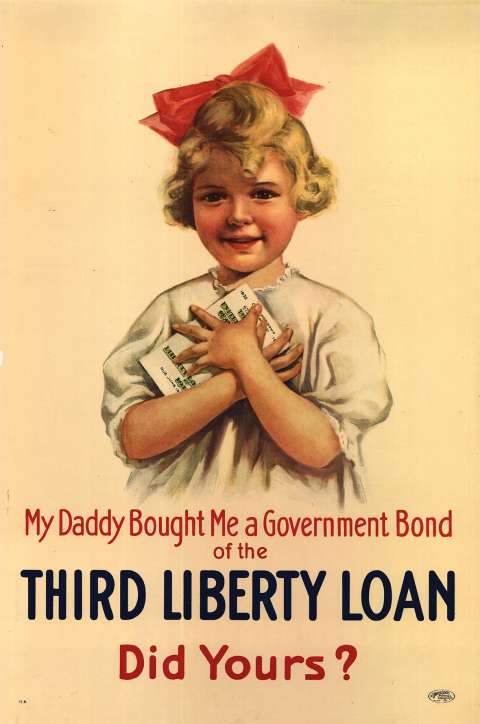

Two months later, on April 6, 1917, Congress and President Wilson declared war on Germany. Wyoming, along with the rest of the country, exploded into super-patriotism. Newspapers throughout the state exhorted citizens to buy Liberty Loan Bonds. The May 24, 1917, Pine Bluffs Post reported that bonds, maturing in 30 years, paid 3.5 percent interest and were available in denominations from $50 through $100,000. The first bond issue was for $2 billion.

"What would George Washington or Abraham Lincoln think of the American who failed to buy United States Liberty Bonds?" admonished the Douglas Enterprise on June 12, 1917. Can't afford to buy a bond? See your local banker for "easy terms," suggested another short item in the same issue.

As the summer of 1917 progressed, communities organized parades and other activities to boost support for the war. A planned parade in Basin, Wyo., was rained out, and an event substituted at the Rex Theater, reported The Big Horn County Rustler. There were songs and speeches, one of the latter promoting the American Red Cross, and another informing citizens about the purpose and activities of the Council of National Defense.

As the summer of 1917 progressed, communities organized parades and other activities to boost support for the war. A planned parade in Basin, Wyo., was rained out, and an event substituted at the Rex Theater, reported The Big Horn County Rustler. There were songs and speeches, one of the latter promoting the American Red Cross, and another informing citizens about the purpose and activities of the Council of National Defense.

Edmund Nichols, a judge from Billings, Mont., stated in his speech, "I cannot understand the hesitancy of some people in buying a bond." Judge Nichols’ remarks suggest that despite overwhelming social pressure to buy bonds, not everyone was doing so.

The Sedition Act

On May 16, 1918, 13 months after America entered the war, President Wilson signed the Sedition Act, aimed at suppressing German sympathizers and unpatriotic talk in general. U.S. attorneys' offices in each state received reports of suspected spies or seditious activity and had to investigate each complaint and decide whether it was valid.

Many Wyoming citizens reported the suspicious behavior of their neighbors and community members to their county attorneys, who in turn reported to C.L. Rigdon, U.S. attorney for Wyoming. Despite hundreds of reports, however, few cases were prosecuted.

Sometimes people took advantage of the espionage and sedition laws to take revenge on a neighbor in an ongoing dispute, or to even up a score. In one case, a woman caught her husband cheating on her, had him arrested for adultery and reported him as a spy.

The One Hundred Percent American Society

Patriotic organizations proliferated. The One Hundred Percent American Society had a chapter in almost every Wyoming town. The Cheyenne chapter's constitution, article three, stated, "The object of the Society shall be to promote patriotism and to aid and assist the United States Government in the prosecution of the war against Germany and its allies to the fullest extent, and to discountenance and suppress all disloyalty, and to aid and encourage the vigorous prosecution and punishment of all persons seeking to interfere with or hamper the successful prosecution of the war."

The May 2, 1918, Wyoming State Tribune reported, "When an order by the school board to burn all the German text books in the Lander high school was not complied with as quickly as some of the more radical pro-Americans around here would have wished, a group of them … got hold of the books Monday morning, carried them to the business center of the town, and there, in the presence of a large crowd, made a bonfire of them."

The article continued, "The board's order was made at the request of the One Hundred Per Cent American club, which also demanded that "the teaching of German be discontinued."

Anti-German sentiment

People with German names had to be careful. In one of the two espionage cases prosecuted in Wyoming, the German-American defendant, John Leibig, had been a respected member of his community before he was accused. Ranching for about 20 years in the Leo community, about 70 miles northeast of Rawlins, Wyo., Leibig had become a naturalized American on Jan. 24, 1905.

In August 1917, an anonymous accuser reported him for treason and for advocating draft resistance. His standing in the community was further complicated by the fatal shooting of a neighbor, Louis Senften. The two men had been involved in an ongoing quarrel, and Leibig was the only witness to Senften's death, on Oct. 20, 1917. Previous to his death, Senften had also formed a partnership with two other neighbors to purchase Leibig's property.

Charged with Senften's murder, Leibig was acquitted but still had to stand trial for 11 counts of espionage. Neighbor after neighbor swore to specific charges. In June 1918, Leibig entered a plea of "guilty," possibly a plea bargain. He was sentenced to a year and a half in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kan., which President Wilson later commuted to one year.

Efforts to strip him of his citizenship continued into 1922, through the U.S. attorney for Wyoming, Albert D. Watson, but it is not known who initiated these attempts or why. As a convicted felon, Leibig had already lost his citizenship.

Historian Phil Roberts, in his analysis of the Leibig/Senften episode, has suggested that Leibig's neighbors may have had two possible motives for reporting him and possibly making extra efforts to jeopardize his citizenship: At the time Senften died, he had not concluded the purchase of Leibig's property, so ownership was not resolved for the remaining prospective buyers. By driving Leibig away, and making sure he was denied any right to claim his ranch, they could better secure that property. The second motive, Roberts suggests, was to punish Leibig for Senften's murder, since the courts had refused to. That is, Roberts suggests, his neighbors used the espionage law instead of lynching him outright.

Life on the front

Of the 11,393 Wyoming men who served in the war, not all fought overseas, but those who did were stationed in France. Many were part of the 148th Field Artillery in the Sunset (41st) Division; others served in the 91st Division. Conditions for soldiers on the front were grueling. When it rained, there might or might not be shelter, but there was sure to be mud. Food for the common soldier ranged from hard tack to beans and bread, or sometimes hot, fresh doughnuts furnished by Salvation Army women, cooking in huts and dugouts hidden in the French woods. Bathing was a luxury; fleas and lice were added to the soldier's trials. Fighting men were always tired, and could sleep anywhere, as they often had to, perhaps on a stack of bread, or sitting on a box in the bottom of a truck, with a helmet for a pillow. And there was the chronic danger of enemy fire.

Civilian life

Life at home was nonstop work, especially for farmers and ranchers who had lost much of their labor force when young men were drafted or volunteered. At the same time, prices for agricultural goods had skyrocketed. Demand was high because war-ravaged Europe could not provide food for itself.

Wheat prices tripled, from 76 cents a bushel in 1912 to $2.49 in June 1917. In August of that year, the government set prices at $2.20 per bushel for the following year's crop. The price of beef also rose dramatically, and the U.S. Food Administration granted ranchers a partial exemption from the prohibition on grain hoarding so they could store feed for the winter.

Wool, 27 and a half cents a pound in 1915—already a high price compared with the previous 30 years—jumped to approximately 50 cents in 1917 and was fixed by the War Industries Board at 55 cents a pound for 1918. Producers of these agricultural goods prospered, but also had to pay higher prices for the items they purchased: clothing, groceries, machinery and equipment.

Coal and oil extraction also boomed. Between 1916 and 1918, oil production in Wyoming doubled, from 6 million barrels to more than 12 million. The state’s coal production mounted from 8.8 million tons in 1917 to more than 9 million in 1918.

Wyoming women worked hard preparing bandages and knitting vests, jackets, scarves and wristlets. They also raised money for the Red Cross, YMCA, Salvation Army and United War Work. Volunteers, mostly women, collected nearly $4,500 for the Soldiers' Book Fund Campaign. The Army earmarked this money for technical books unlikely to be donated. Members of the American Library Association in Wyoming, through directors in more than 60 towns throughout the state, also collected 20,538 books to supply libraries in Army camps.

Politics

Democratic Gov. John B. Kendrick, elected in 1914, ran for the U.S. Senate in 1916 and won. He did not resign the governorship, however, until after the end of the 1917 session of the state legislature. He took his Senate seat March 4, 1917, just five weeks before the nation entered the war. Secretary of State Frank L. Houx became acting governor, serving through January 1919, the entire duration of U.S. involvement in the war. Following the dictates of the federal government, as did all the other governors, Houx oversaw the activities of the state's Council of National Defense. Houx also supervised county draft boards and recruitment for the National Guard.

The end of the war

On Nov. 11, 1918, Germany requested an armistice; the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919. Thousands of Americans, including many from Wyoming, were demobilized near Cheyenne through Fort D. A. Russell, which had also served as a major mobilization point at the start of the war.

Gov. Robert D. Carey, who had won the 1918 election, appropriated $10,000 for a fund to welcome the soldiers home. There are apparently no records of how this money was spent. However, plenty of projects sprang up to ease the soldiers’ transition back to civilian life.

The Wyoming State Tribune reported on March 24, 1919, "ninety-eight per cent of … [returning soldiers] will get their own old jobs back, or a job equally as good." This effort was coordinated by Edward P. Taylor, U.S. Labor Commissioner for Wyoming.

An article in the same issue announced that the YMCA National War Work Council had opened headquarters in downtown Cheyenne. The Council expected to facilitate soldiers' travel home and to funnel information to them from various agencies such as the U.S. employment bureau.

By order of the War Department, the War Camp Community Service also planned a soldiers' club in Cheyenne. The club was to include a lounge, writing room, pool tables and a room for pressing uniforms and shining shoes.

Four bond drives were held during the war, all Liberty Loans, and one bond drive was held after the war—the Victory Loan. Wyoming residents purchased $23.6 million worth of Liberty Bonds. Victory Bonds paid 4.75 percent, and Wyoming purchased $7.2 million of these. Charitable donations in Wyoming totaled an additional $1.4 million, with individuals giving, giving, giving, "until it hurt."

Memorializing Wyoming’s fallen soldiers

During Wyoming’s 1919 legislative session, the House of Representatives introduce House Joint Resolution No. 9, appropriating $2,000 "to have placed in the Capitol rotunda, a suitable tablet of bronze, upon which are to be inscribed the names of our brave heroes who shall have given their lives for justice and liberty." There are 468 names on the tablet. An additional 881 Wyoming men were wounded in the war

The tablet is "inaccurate," notes John Goss, director of Wyoming Military Department Museums. His research and that of his colleague, Johanna Wickman, reveals that the number of dead does not include Navy men; also, some of those listed may not have been Wyoming men. This could have happened when a relative of a fallen soldier sent in his name—and the relative was a Wyoming resident but the soldier was not. The actual total of Wyoming men may be closer to 450. Thus, some percentage of the information gathering after American forces returned home was inevitably haphazard, reflecting the stress and chaos of war.

Resources

Primary Sources

- "Constitution of the 100 Per Cent. American Society of Cheyenne, Wyoming." H71-9, Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- Goss, John, Director of Wyoming Military Department Museums. Telephone interview with the author; personal email to the author; Dec. 8, 2016.

- Olson, Ted. Ranch on the Laramie. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1973, 217-218.

- Wyoming Newspapers. Accessed Nov. 18, 21, 28, 2016, Dec. 1, 2, 6, 2016, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov:

- The Big Horn County Rustler, June 8, 1917.

- The Casper Daily Tribune, June 9, June 16, 1917.

- Cheyenne State Leader, Nov. 17, Nov. 22, Nov. 25, 1917.

- Douglas Enterprise, June 12, 1917.

- Laramie Republican, April 9, April 18, 1917.

- The Pine Bluffs Post, May 24, 1917.

- The Powell Leader, Nov. 22, 1917.

- The Riverton Review, June 15, 1917.

- The Sheridan Post, June 5, May 25, 1917.

- The Van Tassell Pioneer, June 8, 1917.

- Wyoming State Tribune, May 2, 1918; March 24, May 2, 1919.

- The Wyoming Tribune, Aug. 29, Nov. 17, Nov. 24, Nov. 25, Dec. 5, Dec. 22, 1914; Jan. 5, Oct. 19, Nov. 11, 1915; Nov. 23, April 6, 1917; Jan. 1, 1918.

- Wyoming State Legislature, 1919. "House Joint Resolution No. 9." Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum, Casper, Wyo.

Secondary Sources

- Beard, Frances Birkhead. Wyoming from Territorial Days to the Present. Vol. 1. Chicago and N.Y.: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1933, 591, 609-616.

- Cassity, Michael. "Wyoming Will Be Your New Home ... Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming, 1860-1960." Cheyenne, Wyo.: Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, 2011, 205-213. Accessed Dec. 5, 2016, at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/homestead/pdf/historic_context_study_011311.pdf.

- Davis, Paul M., and Hubert K. Clay. History of Battery "C," 148th Field Artillery, American Expeditionary Forces. Colorado Springs, Colo.: Out West, 1919, 83, 90, 104, 112-113.

- Georgen, Cynde. “John B. Kendrick: Cowboy, Cattle King, Governor and U.S. Senator.” Wyohistory.org. Accessed Dec. 23, 2016, at /encyclopedia/john-kendrick.

- Hallberg, Carl. "Anti-German Sentiment in Wyoming During World War I." In The Equality State: Essays on Intolerance and Inequality in Wyoming, edited by Mike Mackey. Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 1999, 63-74.

- "Interesting Statistics on Defense Activities in Wyoming, World War I." Annals of Wyoming, 14:1, Jan. 1942, 60-64.

- Kilander, Ginny. "'Over There With the YMCA': A Wyoming Educator in French Canteen Service." Annals of Wyoming, 82:2, Spring 2010, 2-13.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. 2d. ed., rev. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1978, 386-410.

- Poeske, Dale A. "Wyoming in World War I." Master's thesis, University of Wyoming, 1968.

- Rea, Tom. "Bob David's War: A Wyoming Soldier Serves in France." Wyohistory.org. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016, at www.wyohistory.org/essays/bob-david's-war-wyoming-soldier-serves-france.

- Roberts, Phil. "Murder in the Freeze-outs: Loyalty, Sedition and Vigilante Justice in World War I Wyoming." First published in Annals of Wyoming 85:1, Winter 2013. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016, at http://wyomingalmanac.com/history_of_wyoming/sedition_act_world_war_i_wyoming_article.

- Sawtell, Maj. W. A., Capt. Frank R. Jeffrey, Lieut. W. S. Griscom, and Lieut. William R. Wright. A History of the Sixty-Sixth Field Artillery Brigade, American Expeditionary Forces. Denver, Colo.: Smith-Brooks Printing Co., [1919], 110-164.

- Spencer, Charles Floyd. Wyoming Homestead Heritage. Hicksville, N.Y.: Exposition Press, 1975, 81-104.

- Trueman, C. N. "Timeline of World War One." Accessed Dec. 1, 2016, at https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-one/timeline-of-world-war-one/.

- "World War One and Wyoming." Accessed Nov. 10, 2016, at http://guides.gowyld.net/content.php?pid=692487&sid=5744273.

Illustrations

- The studio photo of the five recruits is from the Preston Alsop biographical file, Wyoming State Archives. The five men are, left to right, Preston Alsop, Ray Clark, Walter Gizan, H.L. Jones, Robert Hays. The photo of the Belgian soldiers is from the George P. Johnson Collection, Wyoming State Archives. The photos of soldier in front of the “Off to France” backdrop, the nurses in the Senate chambers and the children in the 200 percent parade are all from the Meyers Collection, Wyoming State Archives. All are used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Liberty Loan poster is from the Edward Lyman Munson Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. The photos of the recruits on the Albany County Courthouse steps and of Helen Svenson and her carrots are from the Ludwig-Svenson collection, American Heritage Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- AHC Archivist John Waggener informs us that Helen Svenson was the daughter of the original studio owner, Henning Svenson. Out of focus in the background of the photo is Helen’s sister, Lottie, who later married Walter Ludwig. Walter eventually purchased the studio from his father-in-law and changed the name to Ludwig Studio. The studio, now known as Ludwig Photography, is still in operation in downtown Laramie and remains in the family.