- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Paul Kendall’s War: A Wyoming Soldier Serves In...

Paul Kendall’s War: A Wyoming Soldier Serves in Siberia

In a U.S. Army career spanning three wars and four decades, Paul Kendall, of Sheridan, Wyo., never forgot the moment when his platoon, guarding a Siberian rail station, was attacked one night at 30 below—by an armored train full of Bolshevik partisans.

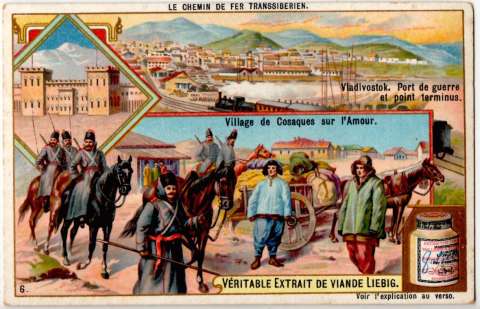

The attack came on Jan. 10, 1920. Young 2nd Lt. Kendall’s 34-man platoon was part of a 90,000-man force of American, Canadian, British, French, Italian and Japanese troops, which had landed 16 months earlier in Vladivostok, Russia, at the Pacific end of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Their mission was to cover the retreat of the famed Czechoslovak Legion, by then allied with the Tsarist Whites against the Communist Red Army in Russia’s bitter Civil War.

The U.S. mission was never particularly realistic, relationships with supposed allies, especially the Japanese, were rocky, and the American experience in Siberia proved to be confusing and frustrating. The night attack was Kendall’s first taste of combat, however, and he and his men performed well.

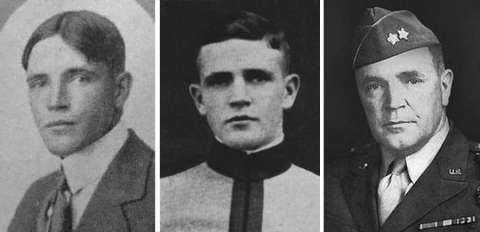

Young Paul Kendall

Paul Wilkins Kendall was born July 17, 1898, in Baldwin City, Kan. His family subsequently moved to Sheridan, Wyo. As a boy, Kendall remembered years later, he was absorbed by a series of books, “The West Point Series,” by West Point graduate Capt. Paul Malone. These novels, with eye-catching, full-color covers of young West Point cadets in all their glory, featured cadet life and were extremely popular.

Kendall attended Sheridan High School, where he captained the football team, and graduated in 1916. He was accepted at West Point, where he arrived the hot, muggy morning of July 10, 1916, as a member of the class of 1920. At the academy he wrestled, played football and served as a cadet sergeant.

The United States entered World War I in April 1917. Facing a high demand for junior officers, the Army accelerated West Point graduations. Kendall’s class graduated Nov. 1, 1918—just ten days before the armistice that brought an end to the war was signed in France.

U.S. troops in Russia

But large pieces of that conflict lingered elsewhere. Pressures of war were one of the immediate causes of the Russian Revolution, which deposed the Tsar and brought the Bolsheviks to power in November 1917. Quickly, the Bolsheviks made a separate peace with the Central Powers—Germany and Austria—and began withdrawing Russian troops from the Eastern Front.

The peace stranded 60,000 battle-hardened, high-morale Czech and Slovak troops, who had allied with the Tsar’s army to fight the Austrian overlords that had ruled their provinces for centuries. Trapped deep in the Ukraine between Russia and Poland, which with the peace had become German territory, the Legion’s officers believed they would be shot as traitors if they surrendered to advancing German troops. They figured their best hope was to travel 5500 miles east on the Trans Siberian Railway to Vladivostok. There they planned to board ships, continue east around the world and rejoin their French and British allies fighting Germans on the Western Front.

Circumstances intervened. When the Russian Revolution devolved into Civil War, the Legion joined the Tsarists in a railroad war that involved heavily armed trains on both sides.

Bound for Siberia

Kendall, meanwhile, underwent three months of infantry training at Camp Benning, Ga. before shipping out—for Siberia via San Francisco. He arrived at Vladivostok March 28, 1919, where he was assigned command of the 3rd Platoon, Company M, 27th U.S. Infantry, nicknamed the Wolfhounds.

The earliest American troops had arrived in September 1918, initially parts of the 27th and 31st U.S. Infantry regiments ordered from garrison duty in the Philippines. Under the command of Maj. Gen. William S. Graves, this 9,000-man American force was supposedly safeguarding American property in the port of Vladivostok, securing the Trans-Siberian Railway, and defending the Czechoslovak Legion, troops of which by then had been arriving at the port for several months.

Difficult service

For Kendall and his fellow doughboys, service in Siberia was austere, and living conditions were primitive. The climate was brutal. One soldier with the 31st Infantry wrote a poem ending, “The Lord played a joke on creation, When he dumped Siberia on the map.”

The U.S. Army lacked adequate cold weather gear, and had to issue muskrat coats, gloves and caps dating from the the Indian Wars on the Northern Plains 40 years earlier. Military duties proved tedious and boring.

In June 1919, Pvt. John Speer threw down his rifle and bayonet at Lt. Kendall’s feet, cursing “I’ll be damned if I can stand it any longer and you can give me six months or a year, I don’t give a damn which.”

Anton Karachun, a soldier in the Machine Gun Company of the 31st Regiment, married a Russian woman, deserted to the Bolshevik partisans, and became a leader fighting against the Americans until he was captured and court-martialed.

Kendall’s 34-man platoon was assigned to guard a portion of the Trans-Siberian Railroad, at Posolskaya Station, Siberia, on the eastern shore of Lake Baikal and 2,000 rail miles west of Vladivostok.

A night attack

At 1 a.m. on Jan, 10, 1920, Kendall’s position was attacked by the Red Russian armored train, the Destroyer, operated by the free-wheeling Cossack, Ataman Semionoff, a self-styled general with dreams of rebuilding the empire of Genghis Khan. The train was directly under the command of Semionoff’s chief, General Nikolai Bogomolets.

With the Americans in the process of withdrawing from Siberia, the Cossacks doubtless expected to catch the doughboys enjoying a long winter’s nap, for the Fahrenheit temperature was 30 below. Unfortunately for the Bolsheviks, Kendall had been warned, and his platoon was alert and waiting. Instead of silence and surrender, the Bolsheviks met hot gunfire and an aggressive counterattack.

Sgt. Carl Robbins climbed up on the locomotive, threw a hand grenade into the cab and disabled it, being killed in the action. Another soldier, Pvt. Homer D. Tommie, also attempted to climb on the Cossack train, was wounded, and fell under the wheels of the train, losing his leg.

The Reds and their train, including Bogomolets, were forced to surrender to Kendall. His small command had overcome a heavily armored and well-armed train manned by no less than 48 Cossacks, killing 12 of them. His platoon lost two killed and one wounded. This proved to be the final combat action of World War I.

A long career

Kendall’s platoon received an unprecedented three Distinguished Service Crosses in this action, with Kendall, Sgt. Robbins and Pvt. Tommie recognized. Kendall captured a Hotchkiss Model 1914 heavy machine gun, manufactured at the Japanese Koishikawa Arsenal, perhaps showing some double-dealing by the Japanese allies.

Just two weeks after the attack, Kendall on Jan. 25 left Siberia with his regiment. He donated the machine gun to Sheridan High School upon his return, and this historically significant gun remains at the Sheridan National Guard Armory today–the last weapon captured in the First World War.

Kendall went on to one of the most distinguished careers of any Wyoming soldier. During World War II he commanded the 88th Infantry Division in Italy; and, in 1952 and 1953 he commanded the I Corps in the Korean War. He retired as a lieutenant general in 1955, and died at Palo Alto, Calif., Oct. 3, 1983. He is buried at the West Point Cemetery beneath a simple soldier’s headstone.

In his incredible military career that spanned 37 years, three wars and four continents, Paul Kendall’s finest moment was as a 21-year old second lieutenant on a dark, frozen Siberian night.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Faulstich, Edith Collection, Hoover Institution, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford, California. Box 19, Paul W. Kendall Folder.

- Kendall, Paul. “Horizontal File: Sheridan High School, Class of 1916,” Sheridan County Fulmer Library, Sheridan, Wyoming.

- Kendall, Paul. Entry in The Howitzer, (West Point, New York: U.S. Military Academy Yearbook), 1920.

- West Point Association of Graduates. “Memorial: Paul W. Kendall, 1918, Cullum No. 6212.” Accessed March 9, 2017 at http://apps.westpointaog.org/Memorials/Article/6212/.

Secondary Sources

- 31st Infantry Association, “America’s Legion: The 31st Infantry Regiment at War and Peace.” Chapter 2- Siberia.” Accessed March 9, 2017 at http://www.31stinfantry.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Chapter-2.pdf.

- Bell, Ulric. “Colonel Morrow Bares Semenoff Atrocities as He Nears America,” Louisville, Kentucky Courier-Journal, January 16, 1922, 1-2. Accessed March 9, 2017 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/119471737/.

- Bibliomaven. “The West Point Series by Paul Malone -Penn Publishing,” July 9, 2009. Accessed March 9, 2017 at http://bookofbibliomaven.blogspot.com/2009/07/west-point-series-by-paul-malone-penn.html.

- Borch, Fred L. III. “Bolsheviks, Polar Bears, and Military Law: The Experiences of Army Lawyers in North Russia and Siberia in World War I.” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, 30:3, Fall 1998, 181-191.

- Filofey, Reverend F. “Asia’s Man on Horseback: The Story of Ataman Semionoff, Adventurer and Empire Builder of the Far East,” Sunset: The Magazine of the Pacific and of All the Far West, 44:4, April 1920, 30-32.

- “Find A Grave Memorial: LTG Paul Wilkins Kendall (1898-1983).” Accessed March 9, 2017 at http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=52686798.

- HomeofHeroes.Com. Website: “Full Text Citations for Award of The Distinguished Service Cross, U.S. Army--Siberia Expedition.” Accessed March 9, 2017 at http://www.homeofheroes.com/members/02_DSC/citatons/02_interim-dsc/dsc_06siberia.html.

- House, Col. John M. Wolfhounds and Polar Bears: The American Expeditionary Force in Siberia, 1918–1920. 2nd Edition. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2016.

- Kindall, Sylvian G. American Soldiers in Siberia. New York: R. R. Smith, 1945.

- Military History Now. “A Long Way from Home: The Czech Legion’s Amazing Trek Across Siberia.” Accessed March 8, 2017 at http://militaryhistorynow.com/2013/06/02/a-long-way-from-home-the-czech-legions-amazing-trek-across-siberia/.

- O’Connor, Neil P., Jr. Website: “AEF Siberia: Everyday Life of a Soldier.” Accessed March 8, 2017 at https://sites.google.com/a/bates.edu/aefsiberia/home/everyday-life-of-a-soldier.

- O’Connor, Richard. “Yanks in Siberia,” American Heritage 25:2, August 1974. Accessed March 8, 2017 at http://www.americanheritage.com/content/yanks-siberia?page=show.

- Smalser, Colonel Robert L. The Siberian Expedition 1918-1920: An Early Operation Other Than War. Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College Thesis, 1994.

- Smith, Gibson Bell. “Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks: The U.S. Army in Russia, 1918-1920. Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, 34:4, Winter 2002. Accessed March 9, 2017 at https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/winter/us-army-in-russia-1.html.

- Willett, Robert L. “The Story of a Turncoat” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, 37:4, Winter 2005, 32-38.

- The author acknowledges the generous assistance of Ms. Carol A. Leadenham, Assistant Archivist for Reference, Hoover Institution Archives.

Illustrations

- The photos of the morning train in the station and of troops training in the snow are from Paul Kendall’s Siberian Scrapbook in the collections of the Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

- The colorful 1903 advertising card is from the author’s collection. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of U.S. troops on parade in Vladivostok is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the armored train is from U.S. Militaria Forum, with special thanks to Bob Hudson.

- The Sheridan High School photo of Paul Kendall is from the historical collections at the Sheridan Fulmer Library. Used with thanks. The photo of cadet Paul Kendall is from Special Collections and Archives, Jefferson Hall, U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York. Used with thanks. The photo of Gen. Paul Kendall late in his career is from Findagrave.com. Used with thanks.