- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Ambition of Nellie Tayloe Ross

The Ambition of Nellie Tayloe Ross

On Oct. 4, 1924, Nellie Tayloe Ross watched as her husband’s coffin was lowered into the ground. William B. Ross had been governor of Wyoming for only a year and 10 months. Twelve days earlier he had suffered severe abdominal pains after a day making speeches in Laramie. It was appendicitis. He died Oct. 2.

Nellie was devastated. She managed not to show it in public when her husband’s body lay in state under the Capitol rotunda in Cheyenne, during the funeral at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, and finally at the graveside. But when she was alone with her brother, she broke down. George Tayloe had come quickly from Tennessee to be with her after William’s death. Nellie couldn’t stop talking about old times, George wrote home to his wife. “When she gets on the past it is terrible for her and I assure you hard on the listeners,” George added.

That afternoon, back at the governor’s mansion, the chairman of the state Democratic Committee knocked on the door and asked a delicate question: Would Mrs. Ross consider running for governor herself? The election was a month away.

Over the next few days, as she and George went around and around on the question of whether she should run, he came to know his sister better. Not only was she shocked and sorrowful over her husband’s sudden death, she was also ambitious. And if she did run, they both understood, ambition was a quality she’d have to disguise. It just wasn’t seemly for a woman to look ambitious.

Early life

Nellie Tayloe Ross was a southern woman, and like many southern women she was gracious, funny and strongly loyal to her family and friends. She was also very smart. She came from Missouri, the border South, a complicated place for people like her who were born not long after the Civil War. Nellie came out of that place and time a complicated woman.

Nellie’s mother’s family, the Greens, owned a large plantation and 100 slaves in northwest Missouri before the Civil War. Their mansion was burned during the conflict, and the family never really recovered. When Nellie’s father, James Tayloe, married her mother, Lizzie Green, shortly after the war, he was soon supporting his wife, her younger sisters and her widowed mother.

He built a smaller house, farmed as much of the land as he could, but made ends meet by slowly selling off pieces of it. Nellie, one of six Tayloe children to live to adulthood, was born in 1876. Finally, James Tayloe sold the place, paid off the mortgage and back taxes, and in 1884 moved the family to Kansas. He opened a grocery store in Miltonvale.

At first, the nearby farms did well and the town prospered. James Tayloe built a large house for his family. But by the end of the 1880s, drought and grasshopper plagues had brought hard times. In 1889, when Nellie was 13, her mother died. Other Green relatives by then had moved to Omaha, Neb, but the Tayloes stayed in Kansas, watching their town and business decline. Nellie finished high school in 1892. Her father eventually lost the store and the house, and the Tayloes moved to Omaha. James Tayloe went to work for his brother-in-law as a bank clerk.

Nellie began teaching piano students and gradually put together two years’ more schooling for herself—enough for a job teaching kindergarten. She taught first in an Italian neighborhood and later in a Polish one, learning not just how to teach, but how big organizations work—in this case, the Omaha public schools.

Later, when she became famous, Nellie let the world believe she’d had a cultivated, upper-class upbringing in Missouri. The truth was more interesting. On the farm and in the store, she learned about hard work. Teaching and running the Tayloe household, she learned to help other people work hard, too.

She also acquired a taste for fine things, mixed with a skepticism about wealth. Money, she knew, might melt away any time. All her life she worried about it. And somehow, it seems fair to say, her father’s business failures, her mother’s death and the family moves all led to an uncertainty in her life that fed her ambition.

William Ross and politics

About 1900, Nellie met William Bradford Ross, a handsome young lawyer, while visiting Tayloe relatives in Paris, Tenn. Both families, Rosses and Tayloes, had strong religious backgrounds, came to Tennessee from North Carolina early in the 1800s, and were ruined financially by the Civil War.

Nellie returned to Omaha, she and William began corresponding and their friendship deepened. Partly for his health, and partly out of the need to strike out on his own, William Ross moved to Cheyenne in 1901. He arrived the day before President McKinley died from an assassin’s bullet, and Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican, became the first Progressive president of the United States.

William B. Ross was a Democrat with political ambitions. In the 1890s, the Populist Party emerged from the more radical, agricultural wing of the Democrats. Populists felt they badly needed lower interest rates on the money they borrowed to keep their farms going each year and lower railroad rates on the crops they shipped to market. In the minds of the Populists and the Democrats, the Republicans were the men that lived in the great cities of the northeast, who owned the banks and the railroads and charged too much for everything.

Populism failed, but its resentments survived and merged with the sensibilities of Americans who felt that poor and middle-class people needed protection from the power of big corporations. Out of these feelings came the Progressive movement, which sought to break up monopolies, protect the poor and weak, make government more effective, provide good drinking water and good sanitation in cities and pure food and safe drugs for everyone.

Three presidents considered themselves Progressives: Republicans Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. William Ross considered himself a Progressive Democrat.

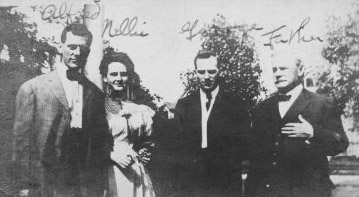

In 1902, William and Nellie were married. Twins George and Ambrose were born the following spring. Alfred was born in 1905, but died when he was 10 months old. A fourth brother, William Bradford Ross II, called Brad, was born in 1912.

William, meanwhile, built up his law practice and started a political career. In 1904 he ran for local prosecutor, and won, but lost when he ran again in 1906. In 1908 he lost a race for the state Senate by six votes. In 1910 he ran for the U.S. House of Representatives and lost again. After that, he and Nellie agreed: no more politics.

Nellie, meanwhile, was already leading a full-tilt social life when her boys were small and her husband’s income as a lawyer was not yet secure. They entertained more lavishly than they could afford. William borrowed money. Sometimes he was short‑tempered and jealous of men who paid attention to Nellie at parties.

Nellie also socialized as a member of the Cheyenne Woman’s Club, where women met to give and hear talks on cultural and political subjects. In later years, Nellie often said she learned her public poise and public-speaking skills there.

|

In 1918, with thousands of young Wyoming men fighting in France in World War I, William again tried politics, despite his earlier agreement with his wife. He lost a close race for the Democratic nomination for governor. In 1919, the nation passed a constitutional amendment prohibiting alcohol, and in 1920, the nation passed another amendment giving women the right to vote.

Wyoming was changing, too. After the war, drought and depression gripped the state. Farms failed, ranches failed and banks failed. The oil business kept booming, briefly. But producers of Wyoming oil bribed top members of Republican President Warren G. Harding’s cabinet in order to drill for government-reserved oil that was supposed to stay in the ground. This Teapot Dome Scandal damaged Republicans everywhere, and 1922 looked as though it might be a good year for Democrats.

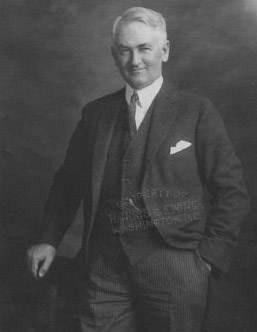

Governor William Ross

Again, despite Nellie’s objections, William Ross yielded to pressure from supporters who thought he had a good chance, and ran again for governor. It was very close, but he won. The Rosses moved into the governor’s mansion.

Almost immediately, Governor Ross began putting his Progressive ideas into action. He got the Legislature to offer low-interest loans to farmers. Because of the depression, state funds had decreased. Ross found ways to spend less, but he also argued that since big corporations, which owned such a high percentage of Wyoming’s wealth, were still untaxed, more taxes fell unfairly on everyone else. He persuaded the Legislature to pass a constitutional amendment to tax coal, oil and minerals. Voters failed to approve the measure later, however. And Ross managed to increase substantially the royalties the state collected each year from production in the Standard Oil Company’s Salt Creek fields north of Casper.

Nellie gave her husband steady support, and he consulted her daily on political questions. Now first lady of Wyoming, she loved the social and political life, yet continued to find it frighteningly expensive. The twins attended boarding schools in the South. Bradford, 10, was still at home. The governor’s salary of $6,000 per year never seemed to stretch far enough, and William’s debts never went away.

Deciding to run

In the days after William’s funeral in October 1924, Nellie’s brother George and other friends advised her not to run for governor. Wyoming was a Republican place and probably always would be, they argued, and the governorship in people’s minds was a man’s job. George feared what a defeat at the polls would do to her emotionally—and she did, too.

Yet she needed the money, or at least some kind of job to support herself and her boys. When William’s debts were paid off, she would own the Cheyenne house they’d kept, but not much else.

Nellie began receiving other offers—some of charity and one of a job as state librarian-- but she was too proud to accept them. George pointed out that if she ran and lost, such job offers would disappear. Triumphant Republicans would offer her no job, nor any pension at all.

More days passed. Still, Nellie still didn’t make up her mind. If she ran, she could say truthfully that she was running out of an unselfish wish to finish the work her husband had been elected for, but it wasn’t quite proper in 1924 for a woman to admit the other truth. She simply wanted the job. She knew politics and wanted to see what she could do. “No one ever wanted it more,” George wrote to his wife. On Monday morning, Oct. 13, still not knowing what Nellie would decide, George boarded a train for home.

The next day, Republicans nominated Eugene J. Sullivan, a Casper lawyer. The Democrats nominated Nellie. Afterward, some delegates came to the governor’s mansion with the news. Finally, 45 minutes before the deadline, Nellie accepted.

Sullivan campaigned hard. Nellie, still deep in her grief, did not, but her backers spoke widely and took out ads on her behalf. U.S. Senator John B. Kendrick, a Democrat, noted “how fitting it was that the Equality State be the first to elect a woman governor.”

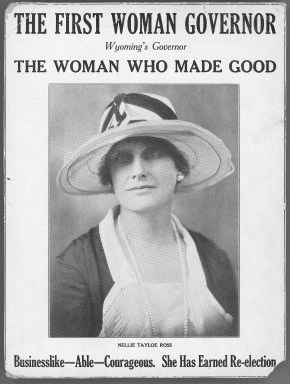

In 1869, Wyoming Territory had been the first government in the world to grant women permanently the right to vote. In 1894, Wyoming Superintendent of Public Instruction Estelle Reel was the first woman ever elected to statewide office. In 1920, women won the vote nationwide. Now, just four years later, Nellie Tayloe Ross was elected the first woman governor in the nation.

She won easily, as it turned out, by 8,000 votes out of 79,000 cast—a much bigger victory than her husband’s was two years earlier. Sullivan had oil business connections, which probably hurt him with Teapot Dome still in the news. Clearly, though, voters’ sympathy for Nellie’s loss had a lot to do with her victory.

The first woman governor

She was inaugurated Jan. 5, 1925—the first woman governor in the nation. It was a tough time to take office. Drought, farm and ranch failures and especially bank failures were spreading hardship across the state. Many people lost their property and their life savings. The oil boom was leveling off. Deadly mine explosions in western Wyoming at Kemmerer in 1923 killed 100 miners, and reminded the state that coal mining remained as dangerous as ever.

Nellie went right to work. The Legislature came to Cheyenne a few weeks later for its once-every-other-year session. Nellie outlined three of William’s policies she wanted to continue—spending cuts, state loans for farmers and ranchers and strong enforcement of Prohibition.

She went on, however, to press for eight additional proposals: requiring cities, counties, and school districts to have budgets; stronger state laws regulating banks; exploration of better ways to sell Wyoming’s heavy crude oil; earmarking some state mineral royalties for school districts; obtaining more funds for the university; improving safety for coal miners; protecting women in industrial jobs; and supporting a proposed amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would cut back on child labor. These ideas all came from solid, Progressive thinking. But Nellie was the first governor to back them in Wyoming.

She was still a Democrat swimming in a sea of Republicans, however. In the end, the legislators supported five of her 11 proposals. With more experience, she might have focused on just three or four, and with more time, she might have made sure the people and their lawmakers understood her ideas before the session began. Equally important for future governors, she managed to beat back several legislative attempts at reducing her powers. Then it was over; the session ended Feb. 22, and with it ended all Nellie’s chances of getting new laws passed.

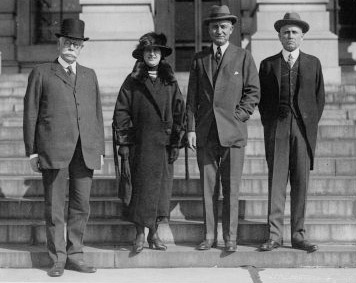

Yet, she was now nationally famous. Women had only had the vote nationwide for a little over four years when Nellie became governor. Eula Kendrick—Mrs. Senator John B. Kendrick—invited Nellie to give a speech in Washington, D.C., to the Woman’s National Democratic Club. This allowed her also to be in Washington for the inaugural festivities in March for President Calvin Coolidge.

Dressed in black, still in mourning, Nellie rode in the inaugural parade and later spoke to the woman’s club, where her audience was large and enthusiastic. The women, Nellie remembered later, seemed pleased to find she was not too mannish and that she had kept her femininity while exercising real power. “I … do not represent the over-powering, masculine, militant type of ‘politician’ that violates their sense of what the Lord intended a woman should be,” she noted in a handwritten narrative of the festivities that she wrote out for herself at the time.

She traveled to Chicago in April 1925 to give a speech at the Woman’s World Fair, and in the summer she spoke at the National Governors’ Conference in Maine. In August, she presided at a meeting of western governors on water issues. Newspaper coverage was positive and abundant.

Yet at the same time, many press accounts gave an impression of surprise that Nellie was doing as well as she was. Newsmen and politicians alike were still puzzled by a few women’s success in politics. Their outer politeness often hid confusion, which came out later as meanness—the men would belittle the women, or ridicule them.

In earlier political movements—against alcohol and for women’s right to vote, for example—American women had learned to work together cooperatively. Now, they were caught off guard by the more ruthless politics among men.

In the summer of 1925, Nellie fired two men from state government who’d been appointed by her husband. She charged Frank Smith, game commissioner, with drunkenness and doing a poor job of handling the fishing-license program. M.S. Wachtel, the state’s law enforcement commissioner, had failed to enforce Prohibition, had taken protection money from bootleggers and had been drunk on the job, she charged.

Afterward, she wrote her brother George that instead of being “high strung and nervous,” as she had often been in the past, she now found she could act coolly throughout the conflict. “Something entirely new seems to have been given me,” she added.

A second campaign

Nellie ran again in 1926. By now, she had a national reputation and the Wyoming press was ready to treat her like a regular politician—and a Democrat. Nearly all the newspapers in Wyoming were Republican. The Republicans nominated Frank Emerson for governor. The Democrats nominated Nellie. She declared she owed nothing to corporations, opposed special interests and sympathized with working people. She challenged anyone to prove her performance as governor had been any less than it might have been simply because she was female.

The press attacked her, saying she hadn’t lowered taxes much and her accomplishments were minor. One Republican newspaper publisher’s wife charged in print that Nellie failed to appoint a single woman to any office previously held by men.

For most of the campaign, Nellie refused to ask people to vote for her just on the basis of her gender. Her supporters were happy to do so, though, and prominent Republican women counterattacked in the press.

Nellie fell back on what she did best. She made speeches. She toured the state in a big Packard car driven by her friend Wilson Kimball, who was running for secretary of state. When the weather was good, they made six or seven speeches a day, and when it rained and the roads got muddy, they didn’t. Republicans and Democrats alike were curious to see the lady governor. Her schedule was jam-packed, and she drew big crowds wherever she went.

Cecilia Hendricks, a homesteader from Garland, Wyo., near Powell in Park County and active in the Democratic Party, wrote home that fall to her family in Indiana:

You know . . . in this campaign the Republicans have constantly argued that no matter how well Governor Ross had done, the Gov’s office is no place for a woman, but is a man’s job. Our [Democratic] speakers have been telling this [story], and then after telling of the schedule she has been filling—more strenuous than any man candidate ever had, because the people everywhere took matters in their own hands and arranged for two or three extra meetings each day—they say they are sure it is not a man’s job, for no man could stand up under such a strain, and no one but a woman could meet all the requirements placed on her everywhere.

Finally, Nellie did play the gender card. The month before the election she said in a speech that if she lost, the whole country would say that the first woman governor was a failure. “I appeal to you,” she said, “not to place me in a false light before the nation.” And with just days to go, she said, “I do not think you will repudiate the first woman governor.”

She lost. The Republicans took all five of the top elected state offices. Nellie’s race was by far the closest of these. She lost by only 1,365 out of about 70,000 votes cast.

The national stage

Even so, this was just the start of Nellie Tayloe Ross’s long career in politics. The following year, she traveled widely and made good money giving speeches throughout the West and Midwest. In 1928, New York Governor Al Smith won the Democratic nomination for president. Nellie, now one of the most famous Democrats and one of the most famous women in the nation, campaigned extensively for him although she disagreed with him on Prohibition.

When Smith lost to Herbert Hoover, Nellie was offered the salaried job of director of the Women’s Division of the National Democratic Committee. She moved to Washington D.C., leaving Wyoming more or less for good. In her new position, she directed the campaign for the women’s vote for Franklin D. Roosevelt.

After Roosevelt took office as president in 1933, he named Nellie director of the Bureau of the Mint, the government agency responsible for making new bills, new coins and melting down old ones. It was a big job, and Nellie was the first woman to hold it. Over the years, and thanks in part to her political experience first in Wyoming and then in national Democratic politics, Nellie became an excellent manager—humane and effective. Managing the U. S. Mint was her true political career. Roosevelt appointed her to three five-year stints in the job, and President Harry Truman, also a Democrat, appointed her to a fourth.

Nellie retired in 1953. She stayed in Washington. She made many smart real estate investments over the years and was finally rich, as she had always wanted to be. She had time for travel now and time for her children and grandchildren.

The legacy of Nellie Tayloe Ross

Yet despite Nellie’s election as the first woman governor in the nation, at least one Wyoming woman of her time criticized Ross for not going far enough. Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard of the University of Wyoming faculty noted in a letter to national woman suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt that the “outstanding reason” Nellie was defeated “was due to the advisors that Governor Ross selected, all men.”

Similarly, more recent historians have criticized the woman suffrage movement as having not gone far enough—as having settled for the vote alone instead of stepping further, and obtaining real political power. It would be two more generations, many historians believe, before women began organizing for real power beyond the ballot.

But woman suffrage was not Nellie Ross’s main concern. She cared about her family, but she also cared deeply about getting things done in the public sphere—that is, about politics. She was born during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant and died in 1977, at the age of 101, during the presidency of Jimmy Carter. She followed her ambition, saw her opportunities, took up the power available to her, and used it.

Resources

Click here to see Nellie Tayloe Ross speak to the public from her desk at the U.S. Mint, shortly after she was appointed director of the Mint by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. With thanks to the American Heritage Center.

Click here to see Nellie Tayloe Ross speak to the public from her desk at the U.S. Mint, shortly after she was appointed director of the Mint by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. With thanks to the American Heritage Center.

Primary Sources

- Nellie Tayloe Ross’s papers, including voluminous correspondence, news clippings, photographs and the newsreel linked above from when she was appointed director of the Mint, may be seen in the archives at the American Heritage Center in Laramie, Wyo. Much of the material has been scanned and is available for browsing as part of the AHC’s online digital collection. See also “Inventory of the Nellie Tayloe Ross papers, 1880s-1998.” Accessed Dec. 6, 2012 at http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=wyu-ah00948.xml.

- Hendricks, Cecilia Hennel. Letters From Honeyhill: A Woman’s View of Homesteading, 1914-1931. Compiled by Cecilia Hendricks Wahl. Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1986. Hendricks and her husband began farming near Garland, east of Powell, Wyo., in 1914. These letters to her Indiana relatives are packed with details of farm, family and politics. Hendricks was active in Wyoming's Democratic Party and ran unsuccessfully for state superintendent of public instruction in 1922. Her letter about Gov. Ross in the 1926 campaign is on p. 518.

Secondary Sources

- American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. “In Pursuit of Equality.” Accessed Dec. 6, 2012 at http://www.uwyo.edu/ahc/eduoutreach/exhibits/equality/index.html.

- American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. “Nellie Tayloe Ross, Wyoming Governor.” Accessed Dec. 6, 2012 at http://www.uwyo.edu/profiles/distinguished-leaders/nellie-ross.html.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 454-460.

- Scharff, Virginia. “Feminism, Femininity, and Power: Nellie Tayloe Ross and the Woman Politician's Dilemma. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 15, No. 3 (1995), 87-106, accessed 2/29/20 via JSTOR at https://www.jstor.org/stable/3346786.

- Scheer, Teva. Governor Lady: The Life and Times of Nellie Tayloe Ross. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006. This is an accurate, readable account, with plenty of attention to Nellie’s childhood in Missouri and Kansas and her fascinating post-Wyoming political career—as well as her time as governor. It’s the principal source for this article.

- Van Pelt, Lori. “Discovering Her Strength: The Remarkable Transformation of Nellie Tayloe Ross.” Annals of Wyoming, 74:1. (Winter 2002), 2-8. This article focuses on how Nellie, with little public speaking experience when she was elected governor, became an orator of national reputation. The Grace Raymond Hebard quote is on p. 8.

- -----. “Nellie Tayloe Ross: Nation’s First Woman Governor Proves Her Mettle in Wyoming,” Wyoming Rural Electric News, August 2006, p. 19.

- Wyoming Public Television. Nellie Tayloe Ross: A Governor First, 2007. See http://www.wyoptv.org/ for DVD copies or for information on rebroadcasts.

For further reading and research

“The 19th Amendment And The Women’s Suffrage Movement.” Parker/Waichman LLP, accessed Jan. 6, 2021 at https://www.yourlawyer.com/library/19th-amendment-womens-suffrage-movement/. A Web page packed with information and useful links.

Illustrations

- The photo of Nellie Tayloe Ross with Eula Kendrick, Grace Coolidge and others in Washington, D.C. in 1925 is from the Wyoming State Archives. All others are from the digital collections of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used, in both cases, with permission and thanks.