- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Battles of Platte Bridge Station and Red Bu...

The Battles of Platte Bridge Station and Red Buttes

A pair of fights on July 26, 1865 in what’s now central Wyoming were two of the most significant battles of the Indian Wars of the northern Great Plains. They resulted in the loss of Lt. Caspar Collins and 27 other soldiers, along with lighter losses among the Cheyenne, Lakota Sioux and Arapaho warriors who attacked them.

The battles were a direct result of the famed Sand Creek Massacre hundreds of miles away in southeastern Colorado Territory the previous November, when Col. John Chivington and 700 troops attacked a peaceful Southern Cheyenne village led by Chief Black Kettle.

Black Kettle’s band had been awaiting peace negotiations with soldiers and government officials at nearby Fort Lyon. But the Colorado troops got there first, and killed about 135 people in the village, more than 100 of them children and women. In the following months, the “entire central plains exploded into war," wrote historian Richard White.

Many Southern Cheyenne bands began moving north across the plains of Colorado, gathering allies as they went among the Lakota and Arapaho. They attacked army posts and stage stations at Julesburg on the South Platte and Mud Springs on the North Platte. By winter they had reached the Powder and Tongue River basins in what’s now northeastern Wyoming—prime buffalo country. There, they linked up with Oglala Lakota and Northern Cheyenne bands.

By May, there was a huge camp of 10,000 or more people on Tongue River. Out of that energy and power, combined with continuing rage and grief over the losses at Sand Creek, the tribes decided it was time to attack the soldiers at Platte Bridge Station, an army post near present-day Casper, Wyo. guarding the westernmost Oregon Trail crossing of the North Platte River.

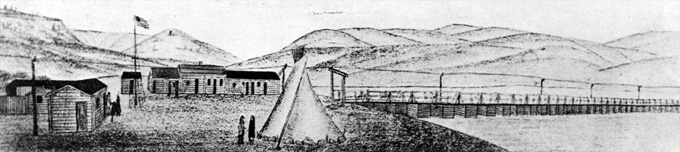

Platte Bridge Station was built in 1862 at the site of a trading post to house storage batteries that powered the Pacific Telegraph line and to warehouse supplies to repair the line. The duties of the soldiers stationed there included protecting and repairing the telegraph line.

Troops at Platte Bridge Station

At that time, the station housed three officers and 60 men from the 6th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry. In the spring of 1865, it was changed from an occasional troop station to a permanent fort. By that time the post was manned by units of the 11th Ohio and 11th Kansas cavalry regiments. Col. Thomas Moonlight of the 11th Kansas, stationed at Fort Laramie, commanded Platte Bridge and other posts along the Oregon Trail. Because of his actions and attitudes, bitterness and animosity grew between the 11th Ohio and the 11th Kansas regiments.

On July 8th Capts. Henry Bretney (Ohio) and James Greer (Kansas) argued over who was in command at Platte Bridge. On the 9th orders arrived putting Greer in command of the post, and placing Maj. Martin Anderson (11th Kansas) in command of a district running 300 miles or more from Ft. Laramie to South Pass. Anderson’s headquarters would be Platte Bridge, about in the middle of the district. The argument and its outcome deepened the hostility between the two regiments.

Anderson arrived at Platte Bridge on July 16. He immediately ordered Bretney and all the Ohio regiment (except four men who knew how to operate the cannon) to the Sweetwater Station near Independence Rock, 55 miles to the west. The Ohioans left on the 21st accompanying Commissary Sgt. Amos Custard and wagons carrying rations and gear for the troops on the Sweetwater.

After Bretney and the Ohio troops were transferred to Sweetwater Station, Platte Bridge Station had men from companies of the 11th Kansas, 3rd U.S. Infantry, and a handful from the 11th Ohio. By the 26th, with the arrivals of small groups of troops on their way east and west, the total number at Platte Bridge Station was 119 men and officers.

The fight at Platte Bridge

At 2 a.m. on July 26, Capt. A. Smyth Lybe of the 3rd U.S. Infantry, Bretney and 10 men of the Ohio regiment arrived at Platte Bridge Station. They were on their way to Fort Laramie from Sweetwater Station to draw pay for their men.

Bretney immediately informed Anderson that Sgt. Custard and his small train of freight wagons, returning to Platte Bridge, were camped at Willow Springs, 25 miles west of Platte Bridge Station, where they had stopped for the night. Because hostile Indians were known to be in the area, Bretney urged Anderson to either send orders for Custard to come in or to send reinforcements. Anderson did neither.

Lt. Caspar Collins of the 11th Ohio had arrived at Platte Bridge from Fort Laramie the previous day, with a corporal and 10 men of the 11th Kansas. Collins was on his way to join his men at Sweetwater Station. Collins and Bretney had breakfast with Anderson early on the 26th.

During the meal Bretney volunteered to take 75 or 100 men and the howitzer and escort Custard to the station. Anderson said no. However, he did agree to send 20 men of the 11th Kansas Regiment.

The Kansas Regiment was due to be entirely mustered out of the Army in little more than a week, and no officer would volunteer to lead the rescue party. The general feeling was that the mission was suicidal. Collins volunteered to lead the party, however, if given more than 20 men.

The North Platte River curved around the west and north sides of the fort. At 7 a.m., Anderson ordered Collins to take 20 men, cross the bridge to the north side of the river, turn west and go to assist Custard. Even though sentries had spotted increasing numbers of warriors on the hills to the north, Collins was ordered to take his men on a route along the tops of those hills, bypassing the road in the river bottom. They would rejoin the road to the west, where it reached higher ground. Thus Collins and his men would remain in view of the station.

After Collins left, mounted on a borrowed, hard-to-manage horse, the troops at the fort saw more Indians west of the river. Anderson sent Bretney and Lybe with 20 men to guard the rear of the Collins party and to prevent the Indians from cutting off retreat to the bridge.

When he reached the top of the hills, Collins spied two Indians cutting the telegraph line and ordered his men to attack. As soon as they began following these Indians, 400 Cheyenne warriors came rushing out of ravines near the river.

Collins wheeled his men to meet the approaching Cheyenne. Because of the hills, Collins could not see the main body of Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota approaching from other directions. His group was soon surrounded. The soldiers tried to fight their way through to the bridge. When one soldier's horse was shot from under him, he called out for help.

Collins returned to help the man. According to historian John McDermott, Lakota warriors had recognized Collins as a friend and let him pass, but the Cheyenne did not know him and shot him with arrows. His horse bolted and ran. Collins finally fell from the saddle at the top of the bluff.

George Bent, the Platte Bridge fight and the attack on the wagon train

George Bent, a son of longtime trader William Bent of Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River and Owl Woman, a Southern Cheyenne, was living with his Cheyenne relatives during this time. In a series of letters he wrote 40 years later to historian George Hyde, Bent recounted events from before Sand Creek to the fights at Platte Bridge and beyond.

Bent was an eyewitness to the battle from the Indians’ side. According to his account, at about 9 a.m., cavalry crossed Platte Bridge and turned west. A smaller group of Indians was waiting in ambush, and once the fight started, the main party of Indians came over the hill some 2,000 strong and attacked the soldiers from the flanks.

"As we went into the troops,” Bent wrote, “I saw [Collins] on a big bay horse rush past me through the dense clouds of dust and smoke. His horse was running away with him and broke right through the Indians. The Lieutenant had an arrow sticking in his forehead and his face was streaming with blood.” He estimated only four or five soldiers escaped alive and said the road was littered with the bodies of dead soldiers and horses.

Besides Collins, four other soldiers of the 11th Kansas were killed in the fight. A fifth was killed after the battle when he attempted to repair the telegraph line, according to McDermott.

Meanwhile, Custard and his wagons had left Willow Springs early on the 26th heading for Platte Bridge Station. About 11 a.m., when the party came over a hill five miles from the station, they were sighted by men there as well as by the Indians. The Indians attacked the wagons.

During the first skirmish, five men became separated from the rest of the party: Cpl. James Shrader and privates Henry Smith, Byron Swain, Edwin Summers and James Ballau. Shrader ordered these men to head for the river, down the hill to their right. Ballau made it across, but was shot when he reached the opposite side of the river. His body was never recovered. Summers was chased south toward Casper Mountain and killed. His body was later recovered. A party of 20 men from the station finally rescued Shrader, Smith and Swain.

Custard's men corralled the wagons and piled cargo underneath them to form a breastwork of sorts. They held off the Indians until about 4 p.m., at which time the men in the station saw smoke rising from burning wagons.

"When the Indians I was with came up,” George Bent later recalled, “the soldiers were already fighting a large body of warriors. . . . Some men were in the [rifle] pits, others behind the barricade under the wagons, and a few sharpshooters were in the wagons, firing through holes cut in the canvas tops."

According to Bent, the Indians’ usual custom was to take no prisoners. He counted 22 dead soldiers. Eight warriors were killed and many more wounded. One unnamed newspaper version of this battle reported that the unarmed soldiers were massacred by the Indians, who tied some of the men to wagon wheels and burned them alive.

Bent called the report "nonsense.” He wrote, “The Plains Indians never tortured prisoners, they never took men prisoners but shot them at once, during the fighting. As to the soldiers being without arms, they were very well armed and put up a hard fight. They stood off a thousand warriors for at least half an hour. Lieutenant Collins and his men, on the other hand, were killed in a few minutes with practically no loss to the Indians."

McDermott stated 21 soldiers were buried on the wagon train battleground, "seven in one grave, thirteen in another, and one in a solitary grave by the river."

Aftermath

Already before the fights at Platte Bridge, plans were underway for a three-pronged, punitive expedition of 2,500 troops into the Powder River country to the north. Gen. Patrick Connor and 1,400 troops managed to destroy an Arapaho village on Tongue River in late August, but the other two columns met with disaster and near starvation.

After a hard winter, some of the tribes were nevertheless ready to make peace the following spring. Lakota, Arapaho and Cheyenne representatives came to Fort Laramie to negotiate, but while they were there Col. Henry B. Carrington arrived on a mission to build forts on Bozeman Trail, which led from the North Platte through Indian territory to Montana, along the east side of the Bighorn Mountains. The Indians left in disgust.

Carrington’s troops built the forts, and white travelers on the trail came under steady attack in what came to be called Red Cloud’s war, for the Oglala Lakota war leader. The Army eventually abandoned the forts, and something like peace held sway for a few years until gold was discovered in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory.

Tensions rose again, Lt. Col. George Custer’s command was rubbed out on the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory in 1876, and finally the tribes came in to reservations in the spring of 1877. Major hostilities flared up one last time on Wounded Knee Creek in Dakota Territory in December 1890, when troops of the Seventh Cavalry killed hundreds of Lakota men, women and children in the last battle of the Indian Wars.

Throughout these decades of warfare with the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota Sioux, it is the stories of these small outposts, such as Platte Bridge Station, that are key to understanding what McDermott calls "the pervasiveness and terror of racial conflict;" lessons that are still important today.

Searching for the battle site

Since at least 1927, when Casper history buff and Midwest Oil Company General Manager Robert Ellison brought two Kansas survivors of the 1865 fights to Casper to help pinpoint the burial sites of the soldiers, people have been looking intermittently for the graves of Sgt. Custard and his command.

Around that time, the fight at the Custard wagon train came to be called, misleadingly, the Battle of Red Buttes, named for the famous Oregon Trail landmark about 10 miles west of the fort, and out of sight of the fort and the battle site.

In recent years, efforts have been led by Fort Caspar Museum Director Rick Young, chairman of the Natrona County Historic Preservation Commission, with the help of local volunteers and archeologists from the office of the Wyoming State Archeologist. They have searched with metal detectors, magnetometers and cadaver dogs. Their results are so far inconclusive.

Various sources differ in the location of the battle, ranging from three and a half to five miles west of present day Fort Caspar. This is a large area to cover on foot looking for the three unmarked graves McDermott mentions. The sites are on private land west of Casper with development beginning to push into the area. Young hopes to locate the site and to be able to preserve it.

Resources

- McDermott, John D. Frontier Crossroads: The History of Fort Caspar and the Upper Platte Crossing. Casper, Wyo.: The City of Casper, Wyoming, 1997, 27-28, 30-31, 42, 44-52, 55-56, 61-77, 82,85.

- Hyde, George E. Life of George Bent Written From His Letters. Edited by Savoie Lottinville. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968, 95-96, 127, 132, 219-221, 223-243.

- White, Richard. It's Your Misfortune and None of My Own: A New History of the American West. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991, 96.

- Young, Richard, chairman of the Natrona County Historic Preservation Commission. Telephone interview with author, May 13, 2013.

Illustrations

- Corporal Moellman’s 1863 sketch of Platte Bridge Station is from the collections American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. Used with permission and thanks.

- William Henry Jackson’s painting of the battle at Platte Bridge is from the collections of the Wyoming State Museum in Cheyenne. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of George Bent and Magpie is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.