- Home

- Encyclopedia

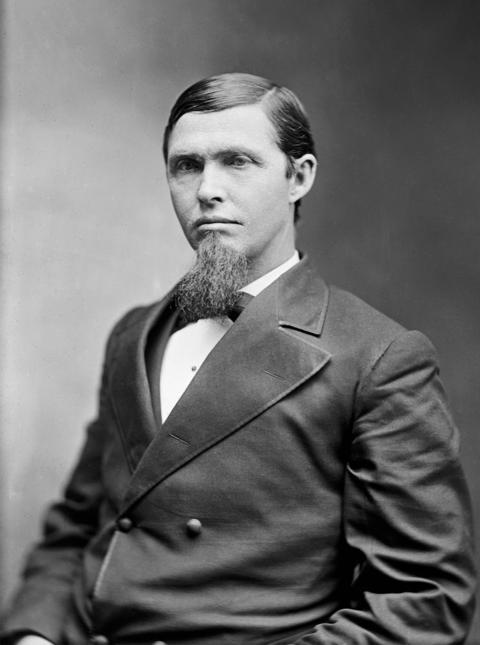

- Preston B. Plumb: Senator of The West

Preston B. Plumb: Senator of the West

“There is no enterprise in the world beyond the ability of the American people to compass when once they address themselves to it. There is no problem their ingenuity cannot solve; there is no obstacle their courage will not overcome; there is no controversy in which they will ever engage from which they will not emerge triumphant.” U.S. Sen. Preston B. Plumb

Preston Plumb of Ohio, Kansas and, briefly, Wyoming had a reputation for being forthright, honest, tireless and fair. As a teenager, he founded a newspaper in Ohio. As a radical abolitionist, he smuggled rifles into Bleeding Kansas. As a U.S. Army officer, he served in the Civil War on the bloody Kansas-Missouri border—and, later, on the frontier protecting emigrants and the transcontinental telegraph from tribal attacks.

But it was when he went into politics, first in the Kansas Legislature and after the Civil War in the U.S. Senate, that his skills and sense of service seem to have been put to their highest use. Because residents of western territories lacked voting representatives in the U.S. Congress—territories each had one non-voting representative in Congress, but no representation in the Senate—many territorial residents found themselves searching for senators from other states to take up their causes.

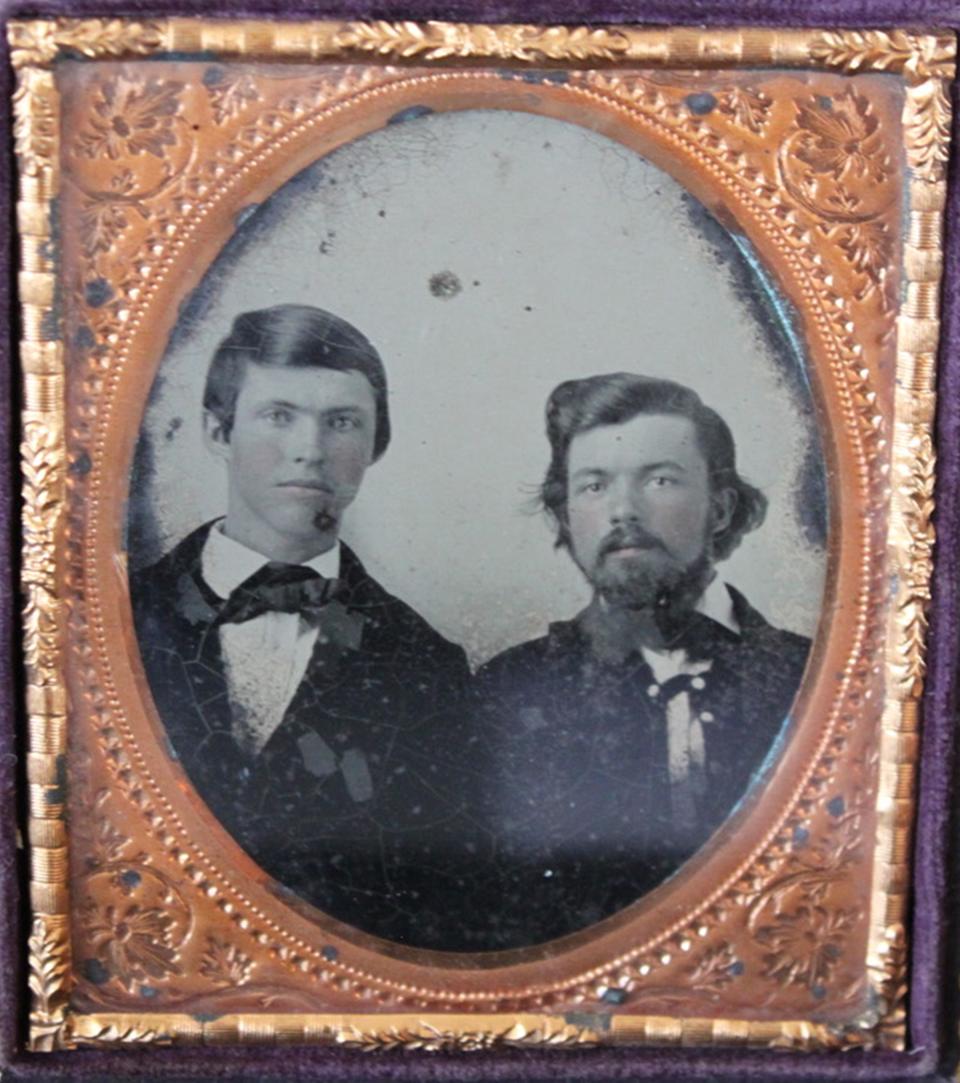

Image

People in Wyoming Territory found that help in Kansas Sen. Preston B. Plumb. Although a Kansan, Senator Plumb was no stranger to Wyoming Territory, as he had served at Platte Bridge Station (now Fort Caspar) in present Casper, Wyoming and at Fort Halleck near Elk Mountain in the summer of 1865, commanding the 11th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry.

Early life

Plumb was born Oct. 12, 1837, in Berkshire, Ohio, to a family of modest means. His father was a wagon maker but his parents desired more for their eldest child and encouraged him to get an education. At 12, he left home and walked to Kenyon College in Ohio where he put himself through school by learning the printer’s trade. He had a knack for journalism and presses, and at 16 started his own newspaper, The Xenia News, in Xenia, Ohio.

At about that same time, Congress passed the infamous Kansas-Nebraska Act, leaving it up to voters in the two territories whether to permit slavery. Kansas became Bleeding Kansas, as armed settlers—proslavery from Missouri, anti-slavery from Ohio and other points north and east—poured into the territory. In 1856, proslavery guerrilla forces attacked and burned much of Lawrence, Kansas, which had been a headquarters for the growing abolitionist Free-State movement.

Becoming a Free-State activist

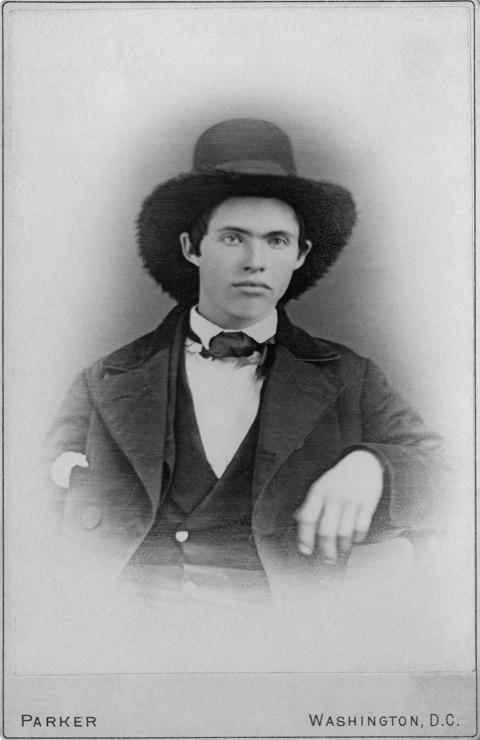

Plumb reported this event in The Xenia News and decided to travel as a correspondent to Kansas Territory and report the conditions there. This planted the seed of his future interest in politics and changed the course of his life from a humble newspaper editor to a Free-State movement activist.

Image

Smuggling arms

In the fall of 1856, Plumb decided to move from Ohio to Kansas Territory, to be more involved in the movement to ensure that Kansas entered the Union as a free state. But he didn’t just move there. Stopping in Iowa, he picked up three wagons of Sharps rifles, thousands of rounds of ammunition, thousands of Bowie knives, hundreds of kegs of black powder and a cannon, to smuggle into Kansas Territory. At 18, Plumb commanded the band of a dozen young men as they walked from Tabor, Iowa to Topeka, Kansas. The men completed their smuggling without any casualties. Proslavery forces searched their wagons but did not uncover the concealed weapons.

Founding Emporia

In October of 1856, Plumb founded the town of Mariposa on the current site of Salina, in central Kansas. Mariposa lasted only a few months because it could not attract enough settlers. Part of the reason was proximity to proslavery Fort Riley. While Plumb was searching for a location to found the town, Robert Wilson, the post sutler and postmaster, stopped him because he wished to disarm him. Plumb told Wilson he should mind his own affairs, and that Wilson could not have his gun, but that he “might get the contents of it.”

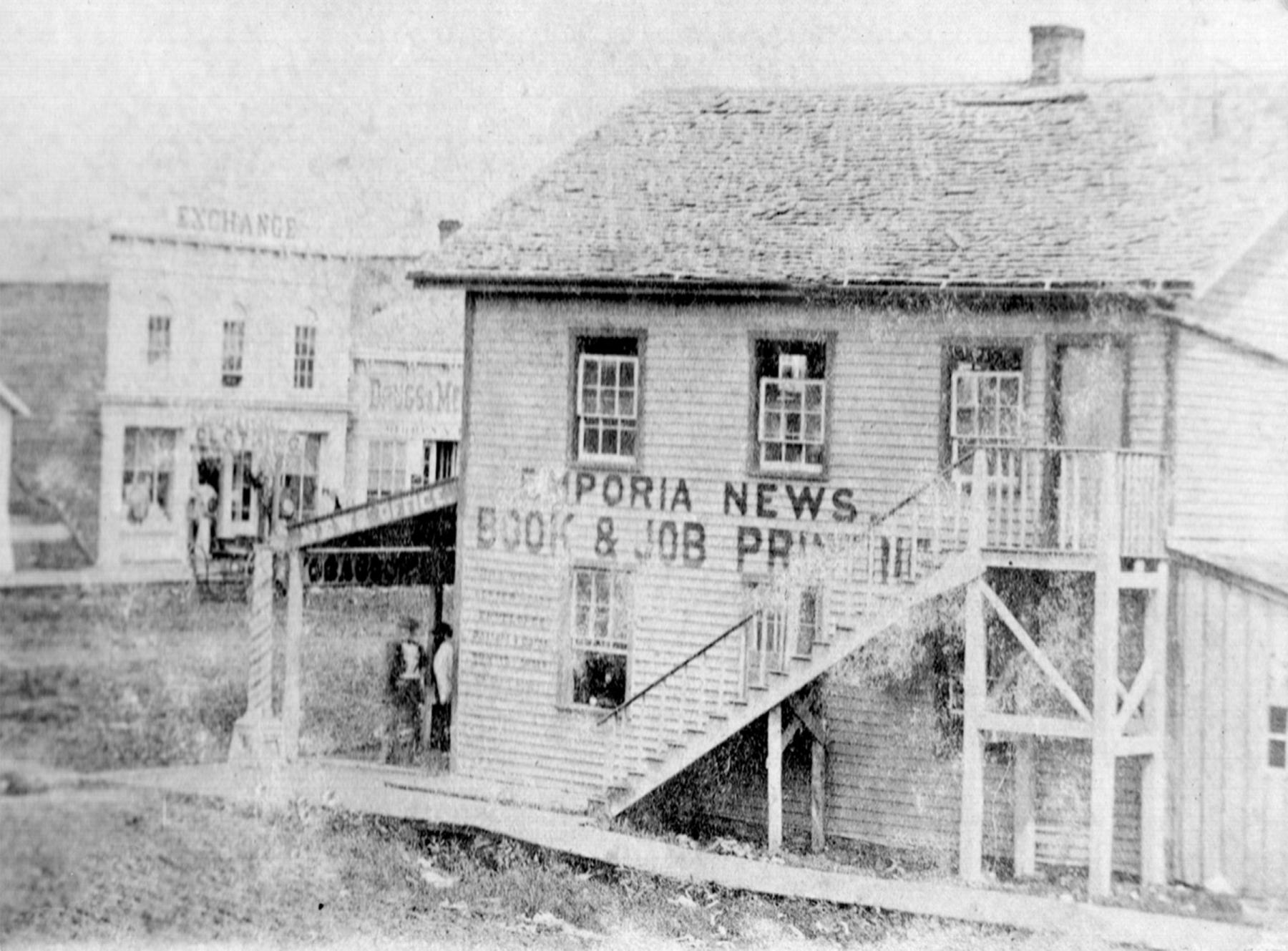

In February 1857, Plumb was one of five men to create the Emporia Town Company and found the town of Emporia, Kansas, southeast of Mariposa. Plumb’s admission to the town company was on condition that he start a newspaper in the new town, to bring in settlers. He was the only member of the town company to permanently settle there, and quickly began planning for a printing press.

This required the now somewhat famous and recognizable Free Stater to travel through proslavery Missouri on his way to Cincinnati to purchase a press. People recognized him on a Missouri riverboat and proslavery men held him to be hung as soon as the boat docked. But a well-known proslavery man found Plumb’s grit and “manliness” respectable, and saved his life.

Image

Politics and the law

Kansas entered the Union on January 29, 1861, only a few short months before the outbreak of the Civil War. The era of Bleeding Kansas had been going on since the 1856 sacking of Lawrence. Proslavery bushwhackers had been fighting with abolitionist Jayhawkers, leaving a trail of destruction in burned-out homes and businesses, massacres and looting on both sides.

Plumb was eager to join the war but did not immediately enlist, as he was serving in the state legislature. He had put himself through law school after starting his newspaper in Emporia and was also working as court reporter for the state supreme court. His last order of business in the legislature was to ensure that Emporia be named the county seat for Breckenridge County (now Lyon County). Once that was done, he resigned from the legislature and the court job to begin recruiting for the new 11th Kansas Volunteer Infantry regiment.

Military service

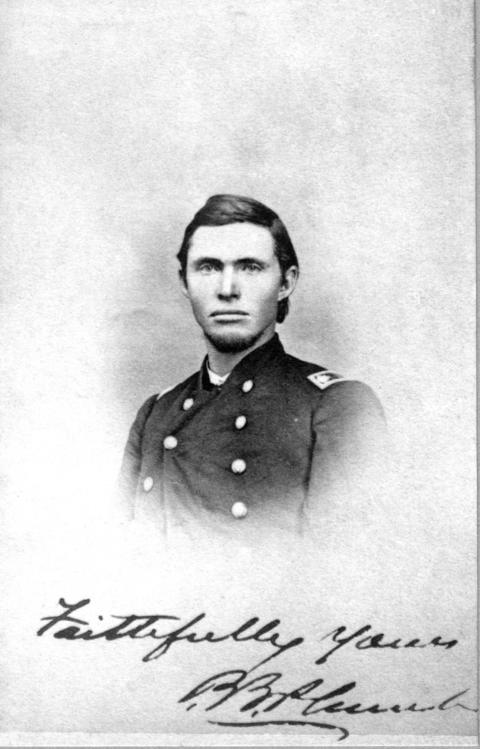

Plumb recruited all of Company C (more than 100 men) as well as many soldiers for Company E. He was promoted to captain of Company C when the regiment mustered in in August 1862. He was then immediately elected major and Kansas Gov. Charles Robinson promoted him to lieutenant colonel in April 1864. The regiment, meanwhile, was converted from infantry to cavalry in the summer of 1863.

Image

During the war, Plumb and the 11th Kansas saw heavy fighting against both the Confederacy and proslavery bushwhackers at the battles of Prairie Grove in northwest Arkansas and Westport in Missouri. Following the surrender of the Confederacy the regiment was sent west where Plumb established headquarters at Camp Dodge south of present-day Casper, Wyoming, then still in Dakota Territory. Plumb and his men were in charge of protecting the telegraph line, which ran along the Oregon-California-Mormon Trail route, from hostile attacks by tribes.

Many of the men who had been with the 11th Kansas since the beginning of the regiment were killed on July 26, 1865 during the battles of Platte Bridge and Red Buttes.

Plumb’s men respected his leadership. Later, Lt. George Walker described their march towards the fight at Prairie Grove in December 1862:

“…we were as near a run as weary men who had marched all night carrying heavy muskets and forty rounds of 69 calabre [sic] ammunition could run. While thus making best of speed we could. Adjutant Williams met us with ‘Hurry up boys or all will be lost.’ We needed encouragement, this was not very encouraging. Then Lt. Col. Moonlight met us with, ‘Hurry up boys or you will miss all the fun.’ We were not in for fun. Then Maj. Plumb met us with, ‘Hurry up boys you are needed.’ We had gone in from a sense of duty and here was the message we needed and every man who heard it was goaded to do his best. In these three sentences or orders I read the character of the men who gave them.”

Marriage and business

Plumb returned home to Emporia in September 1865 and immediately resumed his law practice. He also reentered the state legislature and, in 1867, served as speaker of the house. That same year he married Caroline (Carrie) Southwick of Ashtabula, Ohio and started a family. His law business was lucrative—one of the most successful in the state—but it took him away from home, and he decided to close it to accept the presidency of the Emporia National Bank. In this position he weathered the bank through the banking crisis of 1873 and gained a strong reputation as a charitable and supportive banker.

Image

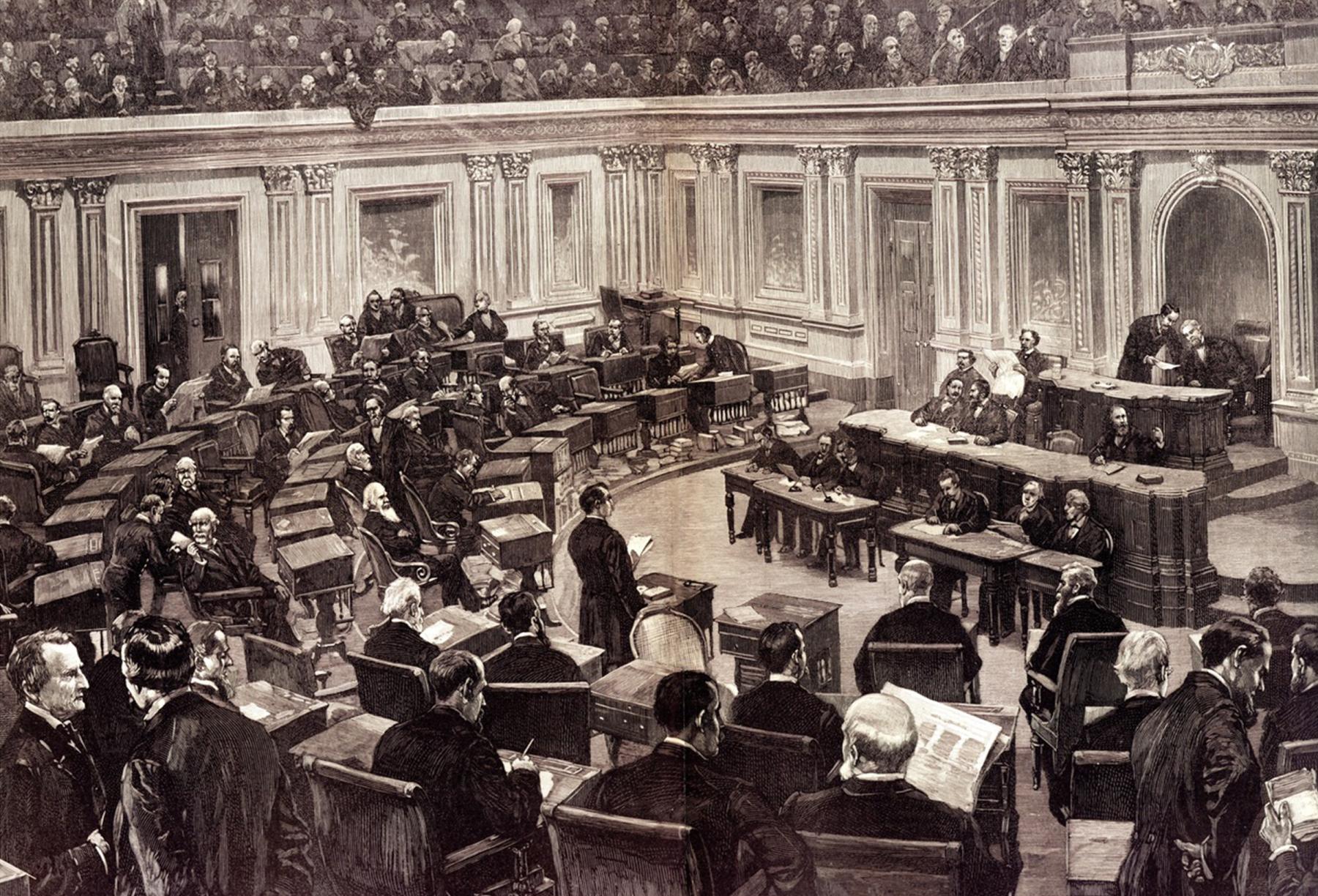

Laboring in the Senate

In 1877, Preston B. Plumb was narrowly elected as a Republican U.S. senator from Kansas. In Washington, his drive and enthusiasm for work quickly made him an outlier. Rather than sitting by for a time and observing the other senators before being “allowed” to introduce his own bills, Plumb worked up his own slate of bills and presented them right away. His memory was photographic. Soon, he was known as a person who could not be intimidated and would take on any cause so long as he felt it just.

Col. O.E. Learnard, another former Free Stater, traveled to Washington D.C. not long after Plumb’s election. Immediately other senators asked him, “What kind of fellow is this you have sent us from Kansas? He makes motions and sustains them with speeches and then alone votes for them! He acts like a wild fellow.” Learnard replied, “Just wait and you fellows will be voting for his motions. He is all right in what he is doing and you will see it soon.”

Plumb subscribed to every newspaper in Kansas and read them all—often while dictating letters and talking with visitors at the same time. His photographic memory allowed him to read his mail while giving an impassioned speech on the Senate floor. It also allowed him to take on far more work than the average senator. If someone asked him for help and he could grant it, he would. Soon, non-Kansas residents began to approach him for help with concerns in their western territories. Many of the causes Plumb fought for in the Senate affected multiple states and territories, with Plumb keeping an eye on representing those territories that did not have a voice in the Senate.

Establishing the Bureau of Animal Industry

One such issue was addressed by H.R. 3967, a bill introduced in 1884 concerning regulations for sick and diseased cattle. At that time in Wyoming territory, the cattle industry was booming, with herds of cattle far larger than had been raised before. The bill sought to create and enforce regulations to prevent sick and diseased cattle from one ranch infecting cattle from other ranches both locally and across state lines, since the cattle were transported for processing.

The bill states, “For the establishment of a Bureau of Animal Industry, to prevent the exportation of diseased cattle and to provide means for the suppression and extirpation of pleuro-pneumonia and other contagious diseases among domestic animals.” Crucially, the bill also funded research to eradicate contagious diseases among cattle and other domestic animals.

At the time, many American ranchers, due to the risk of disease, were having difficulty selling their cattle in foreign markets. This drove prices far down for American beef, leaving local ranchers feeling the weight of the loss. After stiff debate, the bill passed the Senate and created the Bureau of Animal Industry. It lasted until 1953 when it was rolled into the newly established Agricultural Research Service under the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Separating the Department of Agriculture

Another of Plumb’s major accomplishments that directly affected Wyoming Territory was the separation of the Department of Agriculture. Prior to 1888, the Department of Agriculture was not a separate federal department. This meant that agricultural issues did not carry the same weight as issues championed by other cabinet-level departments, such as Treasury or Commerce.

Formally representing an agricultural state and informally the interests of many western states and territories, Plumb focused on agriculture. He saw that this could only be done if the department was elevated to a cabinet level. Plumb had introduced his own bill to remedy this in 1882, but it failed in the Senate. Another bill introduced by William H. Hatch of Missouri in 1888 in the House of Representatives met resistance in both the House and Senate. It was sent to the Committee of Agriculture and Forestry, of which Plumb was a member. The committee, with Plumb’s support, reported the bill with amendments back to the full Senate where he spent several days debating and fighting for it. Eventually it passed, and President Grover Cleveland signed it into law on February 9, 1889.

Chairing the Committee on Public Lands

Throughout most of Plumb’s tenure in the Senate he was chairman of the Committee on Public Lands. Arguably, it was one of the Senate’s most powerful committees. During the 1870s and 1880s westward expansion was in full swing. Railroads were seeking countless land grants and rights of way across the West. Every company that constructed track across public lands needed federal permission, which meant that Plumb approved or denied every one. It is safe to say that Plumb approved nearly every rail line built across the West during that time.

While serving in the Senate, Plumb made great strides toward land and forestry conservation. The Forest Reserve Act of 1891, pushed through the Senate by Plumb as the chairman of the Committee on Public Lands, granted the president the authority to set aside lands as forest reserves from land held in the public domain. President Benjamin Harrison, a longtime friend of Plumb’s, signed the bill into law and immediately created the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve. This reserve included what’s now Wyoming’s Shoshone National Forest—the first National Forest in the country. President Harrison also created Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks using this bill.

Death from overwork

By 1891 Plumb’s hard work was catching up with him. He was receiving approximately 300 letters each day from Americans living in Kansas and a myriad of other states. He answered every one. He often skipped meals for days to work on new legislation or to campaign, and often got only a few hours of sleep each night.

On December 20, 1891, at 54, Sen. Preston B. Plumb of Kansas died in his apartment in Washington, D.C. of a massive stroke. He remains the only U.S. senator ever unanimously reelected by the state of Kansas—senators were still elected by state legislatures at the time—a testament to his popularity and the respect of all political parties. More than 15,000 mourners attended his funeral procession through the state capital of Topeka, with a further 3,000 attending the procession through Emporia.

Preston B. Plumb’s story is an excellent example of how one person can affect the lives of countless others across state lines and across time. His legacy with the Bureau of Animal Industry helped Wyoming ranchers well into the 1950s. His work ensuring the power and autonomy of the Department of Agriculture affects Wyomingites and all Americans who have agricultural interests today.

Image

[Editors' note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, support from which in part made publication of this article possible.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- Plumb, Preston B. American Merchant Marine Speech. Government Printing Office, 1884.

- United States Congress. The Congressional Record. Washington D.C., Congressional Research Service, September 21, 1888 ProQuest Congressional. <accessed December 29, 2022 at https://congressional-proquest-com.wsl.idm.oclc.org/congressional/docvi…;

Secondary Sources

- Wickman, Johanna D. The Forgotten Senator: The Life and Character of Preston B. Plumb. Casper, Wyoming: Bellis Perennis Publishing, 2023.

Illustrations

- Special thanks to the author who provided all the images, and to the people and institutions who maintain them.

- The ca. 1854 photo of Preston Plumb and a friend is from Robert and Lesa Reves’s private collection. The 1857 photo of Plumb in a top hat is from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas. The early 1860s photo of the Emporia News building is from the author’s collection. The photo of Plumb in uniform is from the Mollus-Mass Collection, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pa. The 1877 photo of Plumb is from the Library of Congress. The sketch of the Senate at work is from Harper’s Weekly, Jan. 16, 1886, pp. 40-41.