- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Wyoming Sheep Business

The Wyoming Sheep Business

“There seems to be no doubt that the vast quality of mutton can be grown here, pound for pound, as cheap as beef; and, if so, then sheep-raising must be profitable if cattle-raising is.”

—Silas Reed, surveyor general of Wyoming Territory, from his report for 1871.

In the one known painting of John B. Okie, sheep king of central Wyoming, the subject looks as if he is about to return to a desk at a bank or law firm. Trim but not thin, Okie sits relaxed in a dark, double-breasted suit, sporting a neat tie and stick pin, white shirt and collar stiff with starch. But his eyes, intense with focus, and his sharp, waxed mustache suggest this man did not make his money collecting interest or litigating for Wall Street.

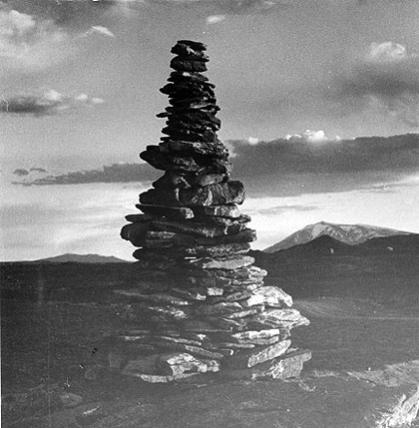

A sheepherder's momument on the Chace Ranch, Carbon County; Elk Mountain in the background. Chuck Morrison Collection, Casper College Western History Center.Okie made his fortune running sheep out of Lost Cabin, Wyo., a town that he owned down to the last board and nail. What made him remarkable was his ability to catch the Wyoming sheep-raising wave at the right time and ride it until he died, in 1930.

By then, sheep raising in Wyoming was twenty years past its prime. The state still had millions of sheep, and some operators were still making money despite the Depression. But there would be no more decades of steady, strong wool and lamb prices, and the free-grass, open-range system that had made the early booms possible was dwindling fast. The sheep business in Wyoming would gradually diminish to a mere shadow of what it was during Okie’s day.

Okie and a handful of others benefited from auspicious timing. They entered the sheep business in 1882. Cattle prices topped $7 per hundredweight that year, a historical high. Not everyone was seduced by the cattle boom, however. Some contrarians took stock in sheep, when the sheep business was still the financial ugly duckling of the range. It must have taken financial restraint not to get into cattle, and instead invest in sheep.

Sheep ranching in Wyoming or the West simply never earned the same cachet as running cattle. When historian Frederick Jackson Turner, in his famous Significance of the Frontier in American History essay, describes "the progression of civilization” marching past Cumberland Gap, he mentions “buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur-trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer”—but doesn’t say a word about sheep. Still, many a savvy 19th century Wyoming flockmaster made a great deal of money in the wool, lamb and mutton business.

It took a while for the notion to catch on: The eastern states and Ohio raised most of America’s sheep. Small numbers arrived in Wyoming as early as 1847 but they, like their owners, were transient. According to Levi Edgar Young’s The Founding of Utah, a Mormon pioneer company that left Omaha in July 1847 and arrived in Salt Lake City on September 19 included 358 sheep.

During the Civil War, high demand for wool for uniforms led to high prices, which encouraged production worldwide. The global supply of wool increased more than a third between 1860 and 1870; a large part of the gain occurred in the first half of the decade, “when the cotton famine was present,” Chester Whitney Wright noted in Wool Growing and the Tariff.

After the war, demand plummeted and prices crashed. According to a report from the American Historical Association, sheep production after the war, between 1867 and 1871, fell by 75 percent in the mid-Atlantic states and by 25 percent nationwide.

This meant that people who wanted to make money in the sheep business had to be low-cost producers. This drove sheep production west, where grass was free on the public domain. The 1862 Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture estimated that the “cost of keeping sheep was only half as great in the West as in the East.”

Early Sheepmen

The sheep industry in Wyoming had modest beginnings. In 1870, for example, Thomas Durbin brought 900 Mexican sheep – Churros – into Cheyenne for the purpose of turning them into mutton. He ended up breeding them instead.

There’s some debate as to who was the first operator to get into the big herds. Edward Wentworth, in America’s Sheep Trails, claims that title belongs to Morton Post. Wentworth cites a March 13, 1875, Cheyenne Leader article noting, “M.E. Post, our sheep king, has added five thousand sheep to his flock on Pole Creek.”

Yet in his report of 1871, Wyoming Surveyor General Silas Reed gives the woolen crown to Edward Creighton, no stranger to southeast Wyoming. Creighton, according to Reed, had contracted to build telegraph line through what are now western Nebraska and eastern Wyoming in 1861, and ended up running 10,000 sheep in both territories.

In 1873, cattle and sheep operators in southeastern Wyoming Territory formed the Laramie County Stock Growers Association. The purpose was “to advance the interests of stock growers and dealers in livestock of all kinds within the territory.” It wasn’t until 1879 that the cattlemen and sheepmen parted ways. The tension between them increased as sheep numbers increased and, eventually, free grass became scarce. The Wyoming Wool Growers Association did not form until 1905.

During the 1870s another important figure entered the sheep business: Francis E. Warren of Cheyenne. Storekeeper, rancher, territorial governor, briefly state governor and finally U.S. senator for nearly 40 years, Warren owed much of his wealth and power to sheep. A U.S. Senator from Iowa called Warren “the greatest shepherd since Abraham.”

Sheep populations in the 1870s grew steadily in Wyoming Territory. In his annual report of 1878, Governor John W. Hoyt reported that sheep numbers exceeded 200,000 head.

The ascent of the sheep business differed from the cattle boom. Wholesale prices for cattle doubled from 1878 to 1882. From 1881 to 1885, cattle prices rarely slipped below $5 per hundredweight. Sheep prices were more stable. Though they enjoyed strong months, prices stayed between $3.50 and $4.50 per hundredweight until the disastrous winter of 1886-87. At the same time the price of wool, remained flat or slightly declined.

Furthermore, unlike many of Wyoming’s original wealthy cattlemen like Moreton Frewen, Hubert Teschemacher and Fredric DeBillier, early sheepmen tended to be “hand built,” coming from modest economic circumstances, according to present-day Wyoming Stock Growers Association Executive Director, Jim Magagna.

As historian David McCullough reminds us, Teschemacher decided to become a ranchman after reading a newspaper in Paris. In contrast, J.B. Okie never left his native land before he came west from Washington, D.C. to Rawlins in 1882. Though he came from an upper middle-class family and borrowed his $4,500 seed money from his mother, Okie spent three winters in a dugout on Badwater Creek, a tenancy most likely unthinkable for Teschemacher or Frewen.

In the 1880s, the boosters and shills lost no time in getting out the word: There was money in sheep. In his 1880 book, The Beef Bonanza or, How to Get Rich on the Plains author James Brisbin felt compelled to include a chapter titled “Sheep-Farming in the West.”

“The Great American Desert is the natural home of the sheep,” he wrote. But when he bought a ranch in Montana a year after his book was published, he did not run sheep.

Wyoming operators like the Cosgriff Brothers–Thomas, James and John – did run sheep, however. These three ex-Vermonters purchased land between Hanna and Rawlins, Wyo. from the Union Pacific Railroad, and eventually built their flocks to 125,000 head. Like Okie, they entered the business in 1882.

Producers began importing bands as large as 10,000 head—from the West Coast. In 1882, Hartman K. Evans and his partner, Robert Homer, drove 23,000 sheep 850 miles from Pendleton, Ore., to Laramie, Wyo. It took them four months.

National production was growing steadily, and much of the growth must have been due to sheep in the West. The wool clip, or total supply of wool, increased in the United States from 264 million pounds in 1880 to 329 million in 1885, or roughly 25 percent in six years.

Economic Adversity

But trouble came. Besides avoiding clashes with cattlemen about grazing, Wyoming sheep operators had to survive three calamities in the next 15 years: the killer winter of 1886-1887, which reduced herds and ravaged prices; a financial earthquake, the Panic of 1893; and the Wilson-Gorman Tariff of 1894, which eliminated the import duty on wool and created a dreaded “free wool” era.

Warren, for example, managed to make it through the winter of 1886-1887, and by 1890 was running 110,000 sheep and his lamb crop reached 25,000. Yet the Panic of 1893 spared no one; it bankrupted even the Union Pacific Railroad. In 1894, the Warren Livestock Company went into receivership as well, with $200,000 in debts. Wyoming wool revenue in 1894 was roughly half of what it was in 1890.

The Cosgriffs apparently survived the Panic. In 1895 the brothers sent the largest shipment ever of Wyoming wool-- 800,000 pounds—via that same bankrupt railroad to Boston.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that Warren testified before Congress in 1894 that Wyoming could not survive without a wool tariff. “We can not compete successfully in any part of the United States with Australia in raising wool,” he said, noting that the state’s production costs were too high. “The condition of sheep and woolgrowing is very severely depressed, more so than any other business in the State and growers are greatly discouraged,” he added.

The lack of federal support for wool did have one silver lining: Producers began raising more lamb and mutton. Previously, sheep—most of them Merino or crossbred Merinos —were raised for their wool. Now Rambouillet, Shropshire, Cotswold and Delaine Merinos—a breed created for wool and meat production—were being introduced into herds and making sheep dual-purpose animals.

The Dingley Act

Warren had a strong affiliation with the American Protective Tariff League, one of the leading anti-free trade organizations of the day. The Wyoming senator chance to support Congressman and fellow Republican Nelson Dingley, Jr. of Maine and his Dingley Act, which doubled any historical tariffs on wool.

The Dingley Act of 1897 started a second boom in sheep. By 1890, there were 712,500 sheep in Wyoming. By 1900, Wyoming sheep had passed the 5 million mark. As for cattle, Wyoming counted 1.5 million of them in 1895 but by 1898, one year after the passage of the Dingley Tariff, there were only 706,000 head.

The ‘Bitterest War’

Given these fast-changing conditions, conflicts between cattle and sheep growers were perhaps inevitable. They centered on grazing rights on the public range. As Frank Benton, a writer and cattleman from Eagle County, Colo., wryly wrote, “a sheep [has] no business eating grass away from a steer.” Violence against sheepmen occurred all over the Rocky Mountain West, but the battle in Wyoming, notes America’s Sheep Trails author Wentworth, was “the bitterest war of all.”

The acrimony began early. Edward Smith, a banker with Beckwith-Gwynn and Company of Evanston, Wyo., testified before the 46th Congress (1879-1881) that “the law of the Territory…prevents trespassing on occupied ranges near settlements, but away from the settlements the shotgun is the only law, and sheep and cattleman are engaged in constant warfare.”

With the passage of the Dingley Act in 1897, the dam holding back cattlemen’s resentment burst, and no part of Wyoming was spared. The Bighorn Basin in particular endured more than its fair share of troubles. One of the most violent acts happened in 1905 on Shell Creek in Big Horn County. A group of masked riders rode into Louis Gantz’s camp and shot, dynamited or clubbed to death 4,000 sheep, shot horses and burned the herder’s sheepdogs alive.

Five years later, In April 1909 on Spring Creek, south of Tensleep, Wyo., armed men approached a sheep camp and killed three men, roasting two in the sheep wagon and shooting the third—and killed the dogs.

Despite this, herds expanded. By 1908, Wyoming led the nation in wool production with over six million sheep valued at $32 million. Wool topped beef, even in value. The value of cattle in Wyoming in 1910 was estimated at $26.2 million, according to a 1913 supplement to the 1910 U.S. Census.

A long decline

The acme was short-lived. By 1914, the number of sheep in Wyoming had been cut by 40 percent. A new tariff law, the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, was passed in 1909, but it was not, as some have claimed the replacing of the Dingley Act that caused the decline. According to Chester Whitney Wright, “the [new] act [of 1909] as finally passed made no alteration in the duties on raw wool as fixed by the Act of 1897.”

The cause was more systemic in nature. Cheap grazing land was disappearing. In 1906, the National Forest Preserve, which would soon become the U.S. Forest Service, began delineating grazing areas and charging five to eight cents per head of sheep to graze them seasonally on federal forest land.

Grangers were taking up land that formerly had been grazed by the flocks. In 1909, Congress passed the Enlarged Homestead Act. This legislation doubled the amount of land deeded to each homesteader from 160 acres to 320 acres. The Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916 doubled homesteads again, to 640 acres. In 1920, dryland farmers, homesteaders and ranchers filed for a record 3.9 million acres of land in Wyoming.

That grazing areas were saturated with livestock didn’t help. Finding grass for millions of ruminants pitted flockmaster against flockmaster. The Rock Springs Grazing Association formed in 1907 for the express purpose of preventing nomadic sheepherders from Colorado or Utah from using Wyoming’s winter range.

Public sentiment against woolgrowers took on an ugly tinge. “Sheep,” wrote G.W. Ogden in a 1910 article, The Toll of Sheep, “are by nature creatures of the desert. The lack of water for a week is no hardship to them. So they ravage like caterpillars, leaving nothing for the cattleman who trails behind, or who has depended for winter pasturage on the invaded land.”

Already by the 1910s, wool and lamb prices had begun a long decline, although there were brief periods of prosperity. World War I drove up wool and lamb prices and then dropped them flat. In 1919, a whole lamb on the hoof in Wyoming could be bought $3.

Finally, in 1934, the Taylor Grazing Act put an end to the old free-grass system that allowed nomadic flockmasters to graze their sheep wherever they could. Similar to the practices adopted on the national forests in 1906, the Taylor act imposed a system of land leases and per-head grazing fees on the unclaimed public land remaining in the West. Sheep growers now needed to own at least a small piece of private land if they were to graze their flocks on specifically designated, public-land leases.

Sheep numbers in Wyoming hit nearly four million during World War II, but that was the last hurrah. In 1984, Wyoming’s sheep population fell below one million. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in 2011 Wyoming sheep numbered only 275,000, not even as many as Okie, Warren and the Cosgriff brothers owned in total in 1890.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Andrews. J. D. Report on Trade and Commerce. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1853, 92.

- Carman, Ezra Ayers. Special Report on the History and Present Condition of the Sheep Industry of the United States, 1892, accessed 9/13/2011 at http://www.archive.org/details/specialreportonh00unitrich.

- Connor, L.G. A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States. American Historical Association Annual Report, Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1921.

- Salmon, D. E. Special Report on the History and Present Condition of the Sheep Industry of the United States. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Animal Industry. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1892, 773.

- U. S. Department of Agriculture. Report to the Secretary of Agriculture. D.C.: GPO, 1893, 552.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Thirteenth census of the United States taken in the year 1910 Statistics for Wyoming. Containing statistics of population, agriculture, manufactures, and mining for the state, counties, cities, and other divisions. Chicago; GPO, 1913, 598 Reprint of the Supplement for Wyoming published in connection with the Abstract of the census. Accessed 10/28/2011 at http://books.google.com/books?id=S1VDAAAAYAAJ&dq=Cattle+in+Wyoming,+value,+1910&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Secondary Sources

- Bancroft, Hubert H. History of Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming. San Francisco, Calif.: The History Company, 1890, p. 800

- “Before the Beginning: Edward Creighton,” accessed 10/312011 at https://dspace.creighton.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10504/40/chapter02.pdf?sequence=1, p. 23

- “Breeds of Livestock,” Oklahoma State University, accessed 10/19/11 at http://www.ansi.okstate.edu/breeds/sheep/.

- Brisbin, James S. The Beef Bonanza. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Company, 1880: 35-70, 93, 139.

- Evans, Hartman K. “Sheep Trailing from Oregon to Wyoming.”

- The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 28, no. 4 (1942): 77.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. 2d ed., rev. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978,296, 367.

- Leeson, Michael. History of Montana 1739-1885: A History of Its Discovery and Settlement. Chicago: Warner, Beers, and Company, 1885.

- Love, Karen, “J. B. Okie, Lost Cabin Pioneer.” Annals of Wyoming 46 no. 2 (YEAR): 173-205, and 47 no. 1 (YEAR): 69-100.

- McCullough, David. Mornings on Horseback: The Story of an Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life, and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003, 327.

- Ogden, G.W. “The Toll of Sheep.” Everybody’s Magazine, New York, Volume 23 (Jul-Dec 1910) 262.

- Rea, Tom. “A Man and his Mansion: J.B. Okie, Sheep King of Central Wyoming,” accessed 9/19/2011 at

- http://www.tomrea.net/J.B.%20Okie.html.

- Reed, Silas. “Stock Raising on the Plains 1870-71.” Annals of Wyoming 17 no. 1 (1945): accessed 9/12/2011 at

- http://uwlib5.uwyo.edu/omeka/archive/files/17_1ocr_v7_7c90590ddd.pdf

- Shallenberger, Percy H. Letters From Lost Cabin: A Candid Glimpse of Wyoming a Century Ago. Casper: Mountain States Lithographing, 2006.

- Turner, Frederick Jackson. “Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Journal name, volume, no., date

- Wentworth, Edward. American Sheep Trails. Ames: Iowa State College Press, 1948, 286-329, 522-544.

- Wright, Chester Whitney. Wool-growing and the Tariff: A Study in the Economic History of the United States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1910, 315.

- _____________________. “Wool-growing and the Tariff of 1890.” Frank William Taussig et. al., eds., The Quarterly Journal of Economics 19 (1905): p. 640. Accessed 10/31/2011 at http://books.google.com/books/about/The_quarterly_journal_of_economics.html?id=WMc4AAAAMAAJ

- Young, Edgar Levi. The Founding of Utah. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1923, 121.

Illustrations

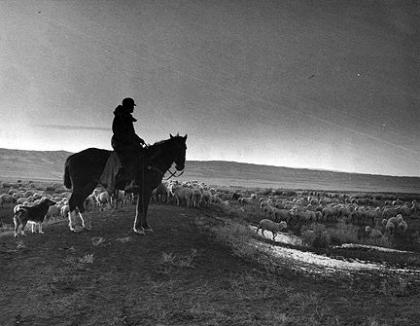

- All three photos are from the Chuck Morrison Collection at the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- For President Lyndon Johnson’s remarks at the Natrona County Courthouse in Casper, Oct. 12, 1964, see http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=26595#axzz1cOEeRvBM.