- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Sticking Power of Ethel Waxham Love

The Sticking Power of Ethel Waxham Love

It was late May 1920, the end of one of the worst cold-weather seasons in central Wyoming. Residents called it “The Equalizer,” because no matter how many sheep, cattle or horses a rancher had the previous October, by the end of that winter, all felt their herds had been devastated. This was one of the hardest periods in the life of Ethel Waxham Love: She was 37, and the ordeal turned her hair white.

Childhood and education

Ethel Phoebe Waxham was born in Rockford, Ill., Aug. 11, 1882, the second daughter of Dr. Frank E. Waxham and Lizzie Leach Waxham. Ethel and her two sisters, Vera and Faith, first went to school at Hyde Park School in Chicago. Lizzie suffered from either consumption or asthma and, in the late 1880s, the family moved to Denver where her husband—a lung and throat specialist—thought the high altitude and dry air would benefit her. However, she died in 1898. Dr. Waxham then married Alice Welles, and the couple had one child, Ruth Eudora.

In 1901, after graduating from East High School in Denver, Ethel enrolled in Wellesley College, in Wellesley, Mass., studying classical literature, Greek, French, German and Latin. Before graduating in 1905, she earned one of Wellesley’s first Phi Beta Kappa keys.

Ethel returned to Denver in summer 1905, working in her father’s medical office. In October, she took a job teaching at the Twin Creek School, about 30 miles south of Lander, Wyo. She boarded at the Red Bluff Ranch, home of Gardiner and Mary Mills, whose son and two daughters attended the school. School terms were held during the coldest months, leaving children available to help with farm and ranch work in late spring, summer and early fall. Ethel had seven students, ages 7 to 15 or older.

In one of her many journal entries, Ethel wrote on Nov. 15, “The color of the white hills against the pale blue of the sky is most exquisite in the world. The cedars are gray with snow, the sage brush white clumps of crystals. Where a long way off the sun touches the tops of the snow covered hills there shines a streak of silver.” Her attachment to Wyoming had begun, but she had no illusions: “It is a cruel country as well as a beautiful one. Men seem here only on sufferance. After every severe storm, we hear of people’s being lost.”

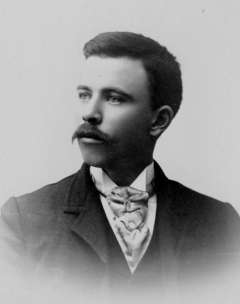

The Twin Creek term ended in April 1906, and though Ethel never taught there again, she corresponded with Mary Mills, and with area sheep rancher John Love, whom she had met at the Mills home. He was born in Wisconsin of Scottish parents, and, after his mother died, raised and educated in Scotland for the first part of his childhood until his father also died and he returned to Wisconsin, where he was raised by relatives.

Early in their acquaintance, Love proposed to Ethel, and she declined. But they became good friends, and he continued to pursue her via their letters. He was 14 years older than she.

Ethel returned to Denver and enrolled in the University of Colorado at Boulder, earning her master’s degree in literature in May 1907. That September, she accepted a job teaching Latin at Kemper Hall, an Anglican girls’ school in Kenosha, Wis. On Oct. 12, she described in her journal how the teachers were paid: “The Mother [Superior], we have discovered, considers any reference to money exceedingly indelicate. Our salaries, which must never be spoken of or asked for, are doled out to us when she sees fit, and in what proportion she pleases. A maid comes about, solemnly, with a silver tray, covered with a napkin. Upon this are little [sealed] notes. … Within—money. But no one knows when these donations may come.”

After one academic year at Kemper Hall, Ethel again returned to Denver in June 1908 and cared for her father and half-sister, Ruth. Dr. Waxham had divorced Ruth’s mother in 1907 for nearly ruining the family with stock market speculations. In November 1909, Ethel accepted a teaching job at Central High School in Pueblo, Colo. But teaching had begun to pall.

John Love, having followed the trials and aggravations Ethel had already faced while teaching, wrote to her in December, “I am indeed sorry to know that you are once more teaching.” Typically, his letters included news about his ranch: “I have lots to worry about here and … am glad that you are not here to share my worry. The past twelve days have been the hardest on livestock that I have ever seen on the range at this season of the year. The snow is deep and the weather has been bitterly cold, 30° below zero, and lower part of the time.”

The tide turned in Love’s courtship on Jan. 1, 1910, when Ethel wrote, “Suppose that you lost everything that you have and a little more; and suppose that for the best reason in the world I wanted you to ask me to say ‘yes.’ What would you do?”

John’s had been a long, persistent effort, including one short stretch in their earlier correspondence when he’d been signing his letters “love and kisses” until she reproved him.

Life on the ranch

Ethel Phoebe Waxham and John Galloway Love were married at her father’s home on June 20, 1910. After an attempted honeymoon trip to Yellowstone Park, about which little is known except that they didn’t get there, the couple settled in at their sheep ranch on Muskrat Creek, about 15 miles south of present Moneta, Wyo. and right about at the geographical center of Wyoming. The country there is very dry. We learn of their experiences through Ethel’s journal entries, chapters for a memoir, her correspondence and the written memories of David, their second son.

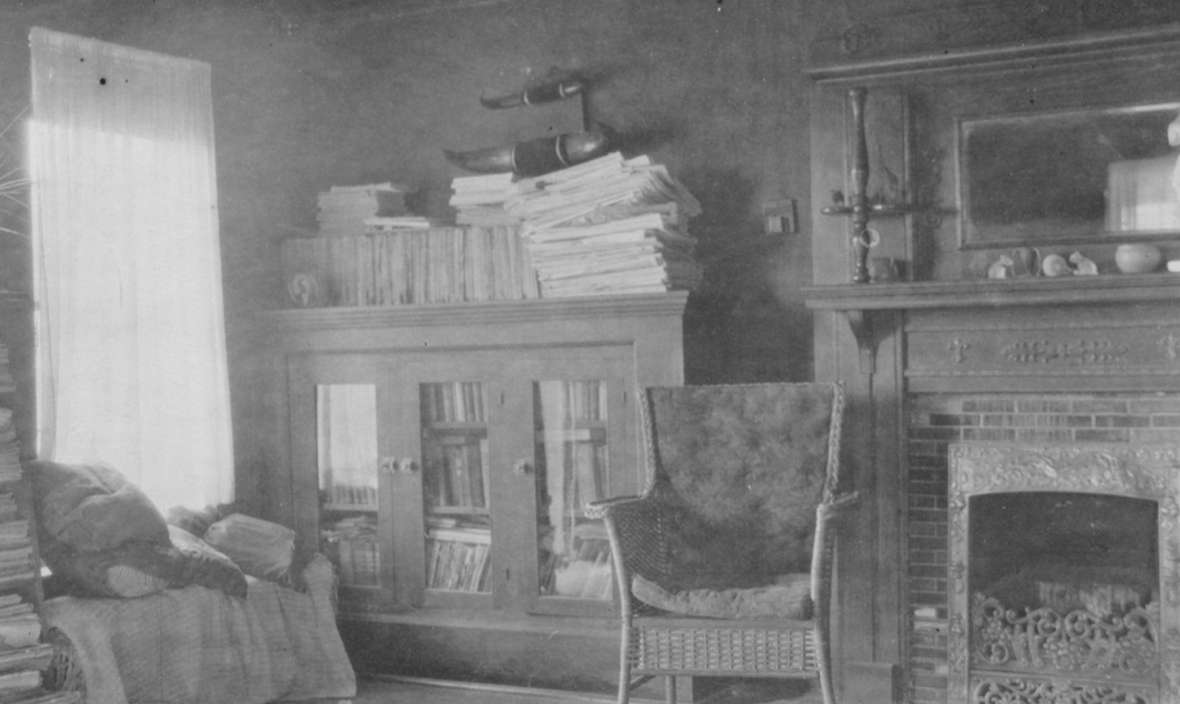

The informal title of the memoir was Life on the Rat. “Rat” was short for “Muskrat” (Creek). About her early days on the ranch, Ethel wrote, “The complete emptiness of the country, treeless, from horizon to horizon, gave me a deeper respect for the men who could endure and make use of the range.”

During their first summer, the Loves took many horseback rides over the countryside, and also spent hours working to improve the interior of the ranch house. Ethel’s father died of apoplexy September 4, 1911, and in early December Ethel traveled to Denver for the birth of their first child, expected later that month. John stayed on the ranch, battling a harsh winter.

Allan Galloway Love was born Dec. 30, 1911. Ethel stayed in Denver with her sister, Faith, until late March, when she returned to Wyoming with the new baby. During that same period, severe winter storms, with 50 to 100 mile per hour winds, killed 2,500 of Love’s sheep. By the time the winter ended, the herd was decimated.

A flood, and financial trouble

In June 1912, Muskrat Creek flooded the house, soaking and dirtying all its contents, from mattresses to furniture to books, food and clothing. Salvage and cleanup continued for months. Not long after the flood, bankers came from Lander and stayed a few days, because the previous year, John Love had been forced to borrow money to cover his payroll and other expenses for the coming year. In 1911, his assets, including equipment and livestock, totaled about $30,400.

The bankers called in the loan, taking everything on the ranch but the buildings, the sheep wagon in which the couple had honeymooned and some disabled large wagons. They missed a few head of livestock that remained on the range, far out of sight.

John offered to release Ethel from their marriage, but she declined.

Rebuilding

One ranch hand remained, working without pay. John, who had already built one dam on Muskrat Creek, decided to finish a much larger dam he’d begun in about 1909. With two reservoirs, he hoped to irrigate crops he wouldn’t have been able to grow otherwise: grain, corn, potatoes and alfalfa. He and their devoted hand, George, finished the dam in early summer 1913, entirely on horsepower and manpower. The volume of earth and rock used during the first stage of construction was estimated at a million cubic feet.

John and Ethel’s second child, John David Love, was born in Riverton, Wyo., April 17, 1913, about 16 months after Allan’s birth. A few months later, a severe hailstorm so strained the big dam that it broke and flooded, ruining most of the crops. Ethel wrote, “Stronger than I are the sun and the storm,/ The thunder that rends the tree in the glen,/ Savage the roar of night-prowling beasts,/ Fearsome am I in forest and fen.”

During this period, Love worked as a sheepherder for a neighbor, Jacob Delfelder, for two years, and was away from home much of that time. Sometimes he brought home motherless lambs, and these became the nucleus for a new flock, although he never again attempted to build a large herd. With the $1,587 Ethel inherited from her father, the couple purchased some cattle, a crossbreed of short-horn and Hereford. Ethel also began raising chickens and selling the eggs—sometimes the family’s only source of cash.

By early September 1915, their income had apparently improved enough for Ethel to travel to Denver to visit Faith, Vera and her two boys. Four months later, in January 1916, John Love could hire a few hands. However, their financial progress did not mean Ethel’s life was free of harrowing experiences.

Some of Delfelder’s hired men brought a pack of bloodhounds from one of his sheep camps to the Love ranch for a run. Somehow, two were left behind when the others were collected to return to the camp. These hounds chased Allan and David, then 5 and 4, into the house. Ethel wrote, “The hounds … leaped furiously at the kitchen windows, high above the ground. They shattered the glass with the small panes. … I had only time to snatch a heavy iron frying pan from the stove and face them.” She beat them back, and they did not get into the house.

The year 1917 brought cars, although the Loves didn’t have one, and a gasoline-powered washing machine for Ethel and their sons. David wrote, “No longer would we boys have to stand beside the old washer by the hour, pushing and pulling the polished hardwood stick which drove the gears that rotated the dolly that agitated the clothes!”

Finances, meanwhile, continued stable or improving.

“The Equalizer”

An October 1919 storm brought snow and mud to the parched range, which had seen a hot, dry summer. In early December, John contracted the Spanish influenza then sweeping the state and the nation. By mid-month he decided to travel to Riverton, 50 or more miles away, for treatment, but the doctor, who could do nothing for him, sent him home. He and David became quite ill.

All the chores fell to Ethel and Allan, 8 years old. Ethel was then suffering from back pain. In an essay, “The Equalizer,” she wrote, “In the numbing cold it took me five hours a day to bring in fuel, carry water and feed to the chickens, and to put out hay and cottonseed cake for the cattle and horses that came crowding about the corrals to be fed. Allan kept them from me with a stick. ...When the barn door was frozen shut, his efforts with mine broke it loose.” Allan also helped bring in the firewood and coal.

John became delirious. All his life, he had chanted Scottish poetry and ballads, and as the winter wore on, his recitations became more and more focused on death.

David recalled his own months of illness, along with things his mother told him much later about that winter, which seemed endless. “At the edge of exhaustion, Mother wondered at times if she were losing her mind to the isolation, the sickness of her loved ones, the cattle dying, the vicious storms, and the cruelty of the land. Totally absent were laughter, encouraging words, and hope. … She reminded herself that three other lives depended on her, and for their sakes she must persevere.”

Then the bull got into the granary, where the only remaining supply of grain and bran was stored for the chickens and other animals. Snatching up an old broom, Ethel beat the bull. Maddened, it stopped eating and lowered its horns. Then Ethel realized what would happen to the rest of her family if it killed her: Allan would walk 15 miles for the nearest help, and almost certainly die in a storm. The invalids would also die within a few days, of cold and starvation.

Instead of panicking, she felt calm, and prayed for help. No longer beating the bull, instead she flicked the broom across its eyes. The bull blinked, appearing confused and bewildered. Ethel continued to flick the broom, annoying but not angering the bull. Then a floor board broke beneath its feet and it fled the granary.

After surviving this battle, Ethel knew she’d get through the rest of the winter. In March, John and David began to recover. Allan spent hours reading to David and helping him build structures with Allan’s erector set. John crooned love songs and memorized Scottish jokes from a small green booklet. Ethel wrote, “The year has thrown his cloak away/ Of cold, of tempest and of rain.”

A cool head

In January 1922, Allan slammed into a barbed wire fence while he and David were sledding. His face was badly cut. John was gone for the day, digging coal, so Ethel could not take Allan to the nearest doctor, in Riverton. Calmly and carefully, she stitched up Allan’s deep cuts without anesthetic. This was surely more difficult for Ethel than past episodes in which she’d amputated a cowboy’s crushed finger, or sewn up a man’s face kicked to pieces by a horse.

None of the subsequent years on the ranch was as bad as the year of “The Equalizer,” but many times the family was short of money due to another severe winter or once, the loss of their savings in the 1924 failure of the Shoshoni bank. Ethel sometimes sold more than 1,000 eggs in a month, and John and the boys trapped coyotes and other small animals for pelts they could sell. The cattle and sheep herds grew and shrank according to the weather and the spring calf and lamb crop.

Rattlesnake or chicken?

Not only did Ethel have courage, fortitude, loyalty and stamina; she had aplomb. In what must be one of the best Love family stories, Allan and David killed a rattlesnake five feet nine inches long, in July 1923. They skinned it, and with the meat Ethel prepared a chicken-like dish for supper.

They had a guest that evening. Bill was a pardoned convicted murderer who had taken a nearby homestead. Before supper, Ethel and John privately warned the boys not to refer to the meat course as rattlesnake because Bill, like many cowboys, probably had phobias about snakes.

But during the meal, Allan and David gradually forgot this. Full of their exploits of the day, they began slipping in more and more comments about snakes until one of them mentioned that some people considered rattlesnake meat delicious.

Bill banged the table with his fist. “By God! If anybody ever gave me snake meat, I’d kill ‘em!”

In the frozen silence, Ethel passed Bill the serving dish with a smile. “More chicken, Bill?”

A daughter, and high school for the boys

Phoebe Elizabeth Love was born on Nov. 16, 1924, in Riverton. Ethel was 42. In June 1925, both boys passed the exam that would allow them to attend high school in Lander, at ages 12 and 13. Ethel took a house in Lander and, with Phoebe, lived there caring for their children for the next two years. John stayed at the ranch but visited his family frequently.

When Allan and David began attending the University Prep School in Laramie, Ethel and Phoebe returned to the ranch. The couple stayed on the ranch until 1947, with Ethel living in Casper during the winters. Phoebe went to school there. After a few winters in Arizona, John and Ethel moved in with David’s family in Laramie.

But “Ethel may have felt her greatest achievements were her children, who all got advanced degrees and went on to lead successful professional lives in engineering, geology, and environmental science,” writes Ethel’s granddaughter, Barbara Love.

Once the children were grown and left home, Ethel served as the first president of Wyoming’s chapter of the American Association of University Women and was active in the DAR, in book groups and in writing classes at the University of Wyoming. “As one of my mother’s letters from the 1950s noted,” writes Barbara Love, “Ethel had a meeting in Laramie, Cheyenne, or Denver nearly every day of the week!”

John died in 1950, Ethel in 1959. As for the ranch, it stayed in the family until 2012, this late date itself testifying to all the hard work and tenacity that Ethel, her husband and their children had poured into it.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Love, Barbara, and Frances Love Froidevaux, eds. Lady’s Choice: Ethel Waxham’s Journals and Letters, 1905-1910. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Chronicles Ethel Waxham’s life from after college graduation until her marriage to John Love.

- Love, Ethel Waxham, and J. David Love. Life on Muskrat Creek: A Homestead Family in Wyoming. Frances Love Froidevaux and Barbara Love, eds. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh University Press, 2018. The story of John and Ethel Love’s life on their ranch on Muskrat Creek in central Wyoming, told through Ethel’s journals, correspondence and other writings; plus the written reminiscences of their son, David.

Secondary Sources

- McPhee, John. Rising from the Plains. New York: The Noonday Press, Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1986. The author tours Wyoming with geologist David Love, learning the record of the rocks and some Love family history.

For further research

- Click here to watch a beautifully restored 1917 Maytag model 43 gasoline-powered washing machine in operation, YouTube, accessed Aug. 28, 2020.

Illustrations

- All photos are from the Love family and used with permission, with special thanks to Barbara Love.