- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Modernizing National Park Facilities: Mission 6...

Modernizing National Park Facilities: Mission 66 in Wyoming

In the economic and patriotic boom that followed World War II, the national park system became overwhelmed. Annual Yellowstone visitation, for example, increased from a wartime low of 62,000 in 1943 to 800,000 in 1946, and then 1.3 million in 1952. Visitors complained of overcrowding, poor service, traffic, interminable lines for toilets and picnic tables, dust, potholes and other gaps in infrastructure; rangers were overworked, underpaid, and suffering in morale.

The parks were being loved to death. Historian Bernard DeVoto published a Harper's Magazine article, “Let’s Close the National Parks,” arguing that the Army should keep visitors out of Yellowstone and other signature parks until the funds needed for meaningful management became available.

By 1956, responding to the crisis, the National Park Service convinced Congress to fund a ten-year initiative to improve the parks’ infrastructure. Aimed at completion by 1966 for the 50th anniversary of the Park Service, it was called Mission 66. With Mission 66, the Park Service sought to accommodate larger crowds by using Modernist architecture and suburban planning principles. Choices in design could ease logistical pressures and reduce administrative costs.

The first and most famous Mission 66 projects were in Wyoming, including the Jackson Lake Lodge in Grand Teton National Park and Canyon Village in Yellowstone. These and subsequent developments proved controversial because they represented a renegotiation of Americans’ relationships with natural beauty. Today, as the Park Service again faces concerns about overcrowding and outdated infrastructure, it’s worth taking a closer look at a previous solution to a similar crisis.

Jackson Lake Lodge

John D. Rockefeller Jr., a driving force behind the 1950 creation of Grand Teton National Park, also wanted that park to appeal to modern tourists. He commissioned renowned architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood, who had designed several previous national park lodges, to design a new complex that broke with traditional rustic style.

Design began in 1950; the building was completed in 1955. For lower costs, Underwood used modern building methods such as concrete walls and a flat roof. To feature a panoramic view of Jackson Lake and the Tetons, he used large banks of picture windows. And to meet travelers’ desires, he added such modern conveniences as in-room telephones, ample parking and convention facilities.

Thus the Jackson Lake Lodge had little of the log-and-stone character of previous “parkitecture”—and critics complained that it was “a concrete monstrosity,” “a steamship without smokestacks,” and a “slab sided concrete abomination.” But buildings in the rustic style were not only labor-intensive to build and incompatible with modern conveniences—they also couldn’t handle large crowds. When the Old Faithful Inn opened in 1904, for example, it had just 140 rooms; the Jackson Lake Lodge opened with more than 300. (Both hotels have since expanded their capacities.) Ever-rising tourist volumes needed to be addressed by better-functioning buildings, even if that meant sacrificing some romanticism.

Rockefeller intended the Jackson Lake Lodge as an example for future Park Service development. NPS director Conrad Wirth, who attended its 1955 opening, was impressed. Trained as an architect, Wirth decided to embrace these principles to guide Mission 66.

Conservation

To tourists, “overcrowding” often meant a line for the toilet, but to management, a bigger issue was how to keep sensitive natural wonders from being trampled. If visitation continued to grow, how could landscapes retain their natural integrity? One answer was segregation of uses. Then-popular suburban land planning techniques created, for example, separate zones for industry, residences and retail—could national parks be similarly zoned?

The old Canyon Hotel (sometimes called the “third Canyon Hotel,” a 1910 remodel by Robert Reamer) sat so close to the scenic Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone that some people thought the hotel overwhelmed the natural feature. In a hallmark Mission 66 project, NPS leaders decided to demolish that hotel and build new lodgings about a mile away. Modern conveniences would be segregated from nature, which would remain “picturesque,” “unspoiled,” “wilderness”—separate from the masses of people. You could enjoy the view of the canyon, and then go eat dinner or gas up the car in a less scenic, less fragile landscape. In this way the canyon wilderness could be enjoyed by larger numbers of people.

But this definition of “enjoyment” typically involved a distant appreciation of scenery—a break from previous environmental philosophies expressed in national parks, which sought to integrate people into natural environments. Consider the Old Faithful Inn, whose pleasures include a close-up view of the adjacent geyser for which it is named. One Mission 66 proposal (never implemented) suggested razing the Old Faithful Inn and building a new hotel in a proposed complex named “Firehole Village” several miles away.

Villages

By zoning human activity away from natural beauty, Mission 66 initiatives created “villages” with hotels, restaurants, shops, gas stations and visitor centers. Yellowstone’s Canyon Village and Grant Village were built along these principles, as was Colter Bay Village in Grand Teton.

The village philosophy also influenced the Park Service’s relationships with surrounding communities. In-park villages were necessary only for vast expanses such as the Yellowstone-Teton complex; a better solution put human-centered development, especially hotels, outside the parks and their pristine nature. Eventually, even some park administrative facilities and visitor centers themselves were located in gateway communities, as with the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area near Lovell, Wyo.

Before automobiles were allowed in Yellowstone, in 1915, grouping buildings close to natural features made sense, because most tourists saw the parks via stagecoach, the equivalent of public transportation. By the 1950s, most national park tourists came in their own automobiles, and happily drove two-lane roads between parking lots. Today, park advocates express concerns that tourists spend too much time in their cars, not enough time immersed with the natural wonders that make the parks special. Meanwhile, as tourist numbers have continued to increase, the roads and parking lots have themselves become the bottlenecks.

Visitor Centers

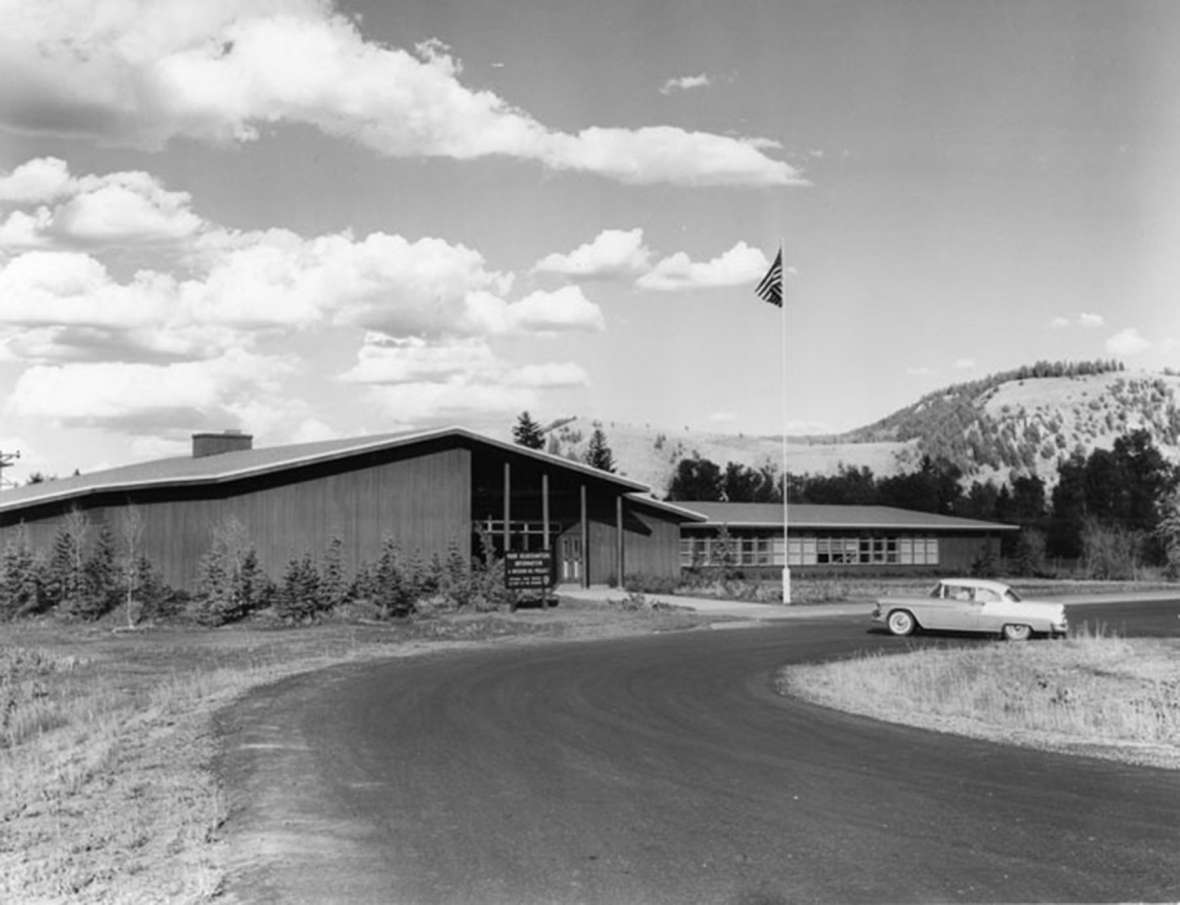

A major Mission 66 innovation was the “visitor center.” The idea was modeled on 1950s “shopping centers,” in part because tourists who needed to learn how to appreciate a park resisted going to “museums” or “education” centers. Visitor centers across the nation have often been admired, both for function and Modernist architectural uniqueness. Two examples are Clingmans’ Dome in Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina and Beaver Meadow in Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. Among the earliest such buildings were two in Grand Teton National Park—the 1956 Colter Bay and 1958 Moose visitor centers—along with Yellowstone’s 1956 Canyon and 1965 Grant Village visitor centers.

Modern materials and prefabricated components made these buildings relatively inexpensive to construct quickly, and kept maintenance costs low. Contemporary stylings generally featured asymmetrical roofs and picture windows. An intentional lack of ornamentation kept the focus on the surrounding wonders rather than the buildings themselves.

Large blocks of windows allowed visitors inside to see the natural features they were learning about. In one sense this architectural style could bring people closer to the parks’ science, spurring an intellectual appreciation of nature. Yet in another sense, a glass wall removed the tourist from immersion in nature. Lost were the spiritual benefits perceived by activists such as photographer Ansel Adams and Sierra Club director David Brower, both of whom condemned the trend.

For example, Adams said that Mission 66 was “built upon a definition [of parks] which justifies the urge to expand and to manage” rather than a definition based in wilderness and reverence. In short, people who loved national parks as an antidote to civilization were frustrated that these modern buildings could make it feel as if the parks were being urbanized.

But was that the buildings’ fault? Tourists flocked to the parks, whose managers were responsible for handling them efficiently. Because these buildings accomplished that goal, they succeeded, and spread, even beyond the Park Service.

For example, in 1966, the Wyoming State Bath House in Thermopolis’ Hot Springs State Park replaced a neoclassical building that had featured temple-style columns. The new bath house had narrow, horizontal blocks of sandstone, a low-pitched roof, and a floor-to-ceiling glass wall—all hallmarks of Modernism that bathers rarely complain about.

In another example, the 1976 Cal S. Taggart Bighorn Canyon Visitor Center in Lovell opened as the first National Park Service facility to use primarily solar energy. Its “Solar Modern” style featured blunt forms, massed walls and floors, and south-facing windows and/or solar collectors. Unfortunately, its solar heating and cooling systems never worked well.

Legacy

High-profile buildings drew attention, but the real success of Mission 66 came from $1 billion in diverse infrastructure investments. The Park Service acquired new lands, including authorization of 70 new units—that is, new parks, historic sites, national seashores and more. The agency also built water, sewer and electrical systems for its visitor and employee structures and expanded and professionalized its staffing. In addition to 95 visitor centers, Mission 66 funds constructed 216 utility buildings, 257 administrative and service structures, 575 campgrounds and 1,239 park housing structures, while building or rebuilding more than 2,700 miles of roads and more than 900 miles of trails.

Without Mission 66, the national parks’ undersized, aging, labor-intensive infrastructure would have failed miserably to handle even the volumes of people it has for the last 50 years. Yet Mission 66’s success arose in part from the way it reinterpreted the national park idea for its era. As that era passed, by the late 1960s, the reputation of Mission 66 was tarnished by the wider culture’s backlash.

Meanwhile, increased attention to broader ecosystems created problems for the Mission 66 vision of segregating development from scenery. For example, although Yellowstone’s Grant Village had been intended to minimize environmental impact by concentrating development in a less scenic spot, that location later proved to be important wildlife habitat. Yet Mission 66 had encouraged a top-down, technocratic decision-making process, rather than a bottom-up, consensus-building process. Alston Chase’s controversial 1986 book Playing God in Yellowstone, which criticized the Park Service for arrogance, included a chapter detailing its lengthy battles with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, among other wildlife advocates, over the construction of Grant Village. The Fish and Wildlife Service questioned the need for commercial development in grizzly habitat, but because of Mission 66, Chase argued, the Park Service had come to favor industrial tourism over ecosystem protection.

In recent years, architects have found ways to merge Modernism and parkitecture, creating buildings that recall a romantic past while still efficiently processing crowds. For example, the 2008 Laurance S. Rockefeller Interpretive Center, in Grand Teton National Park, uses wood and exposed rafters, reflecting the log cabin stylings of the old JY dude ranch that it memorializes. The 2007 Craig Thomas Visitor Center and the 2010 renovation of the Jackson Hole Airport, both also inside Grand Teton, combine glass walls and concrete-based structures with large round wooden columns resembling trees.

Today

The continual challenge of national park management is to balance human use and natural conditions. Growing visitation intensifies that challenge today. For example, some of the earliest Mission 66 successes have failed to accommodate 21st century demands: The Moose Visitor Center was replaced by the Craig Thomas Visitor Center in 2007, Canyon Village was reconstructed in 2016, and Colter Bay is now thought inadequate.

Indeed, in 2019, as the Park Service seeks Congressional funding to address its $11 billion infrastructure repair backlog—which reflects only deferred maintenance, not new construction—managers continue to debate how to accommodate masses of people while preserving the vast natural wonders they come to see.

Resources

Primary Sources

- DeVoto, Bernard. “Let’s Close the National Parks.” (Harper's Magazine, October 1953). In America’s National Park System: The Critical Documents, edited by Larry M. Dilsaver, 1994. Nps.gov, accessed July 9, 2019 at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anps/anps_4d.htm.

- U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service. Mission 66 for the National Park System, January 1956. Npshistory.com, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at http://npshistory.com/publications/mission66-park-system.pdf.

Secondary Sources

- Allaback, Sarah. Mission 66 Visitor Centers: The History of a Building Type. National Park Service. Nps.gov, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/allaback/vct.htm.

- Carr, Ethan. Mission 66:Modernism and the National Park Dilemma. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007. This fascinating book served as the chief source for this article.

- Chase, Alston, Playing God in Yellowstone, chapter 13, “Grant Village and the Politics of Tourism” (New York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1986), pp. 197-231.

- Denzer, Anthony. “Bighorn Canyon Visitor Center.” Society of Architectural Historians. SAH Archipedia, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WY-01-003-0083.

- Ford, Samantha. “Laurance S. Rockefeller Preserve Interpretive Center.” Society of Architectural Historians. SAH Archipedia, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WY-01-039-0067.

- Hert, Tamsen. “Luxury in the Wilderness: Yellowstone’s Grand Canyon Hotel, 1911–1960.” Yellowstone Science13, no. 3 (Summer 2005): 21-36. University of Wyoming Scholars Repository, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at https://repository.uwyo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1024&context=libraries_facpub.

- Howarth, Dan. “Eight Modernist visitor centres from the USA's Mission 66 National Park programme.” Dezeen, Aug. 26, 2016. Dezeen.com, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at https://www.dezeen.com/2016/08/26/eight-modernist-visitor-centres-mission-66-national-park-programme-usa/.

- Humstone, Mary M. “State Bath House.” Society of Architectural Historians. SAH Archipedia, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WY-01-017-0055.

- “Jackson Lake Lodge National Historic Landmark.” Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Wyoshpo.wyo.gov, accessed July 9, 2019 at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/index.php/programs/national-register/wyoming-listings/view-full-list/863-jackson-lake-lodge-national-historic-landmark.

- “Parkitecture, Past and Present.” Whole Trees Structures, Aug. 2, 2017. Wholetrees.com, accessed Feb. 15, 2019 at https://wholetrees.com/parkitecture-past-and-present/.

- U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form. Nps.gov, accessed Aug. 26, 2019 at https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/64501248.pdf.

- Visitation numbers from: https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20Recreation%20Visitation%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=YELL, accessed September 11, 2019.

Illustrations

- The Richard Collier photo of Jackson Lake Lodge is from the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Used with thanks.

- The Jack Boucher photo of the Moose Visitor Center is from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The Mary Humstone photos of the Laurance S. Rockefeller Preserve Interpretive Centerin Grand Teton National Park and of the State Bath Houseat Hot Springs State Park in Thermopolis, Wyo. are from SAH Archipedia. Used with permission and thanks.

- The National Park Service photo of the Bighorn Canyon Visitor Centeris also from SAH Arhcipedia. Used with thanks.