- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Trouble At Lightning Creek: “A Stained Page In ...

Trouble at Lightning Creek: “A Stained Page in Wyoming’s History”

Copyright © 2018 by WyoHistory.org

Just before sunset, on Oct. 31, 1903, 18-year-old Hope Clear, an Oglala Sioux from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, dismounted from her horse to open a gate near Lightning Creek on the Dry Fork of the Cheyenne River about 50 miles northeast of Douglas, Wyo. Two little boys were with her, helping her trail some loose ponies. They had ridden ahead of several of the wagons driven by others in the group. The Indians, headed back to the reservation after a trip to search for medicinal plants, planned to camp near the creek.

But the teenager “saw the white men aiming their guns at me, so I started back to the wagons as fast as I could go.” Shots rang out. Clear did not hear any warnings before the gunfire began. One bullet hit the horse that 11-year-old Peter White Elk rode. The horse fell. The boy scrambled up “and started to run and then he got shot.”[1]

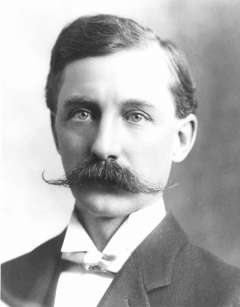

The fighting lasted no more than five minutes. Seven people, including Peter White Elk and Sheriff William Miller, died of wounds incurred during the battle. The white men that Hope Clear saw were members of a posse headed by Miller, sheriff of Weston County, Wyo. The confrontation was in Converse County; Miller was in fact out of his jurisdiction.

Posse members said later that they shouted warnings to the Indians to stop, but that the Indians fired first, in contrast to Clear’s recollection. Miller had tried to arrest the Indians for violating state game laws the day before, but Charles Smith, the Oglala leader of the party that Clear was traveling with, had convinced the Indians that they should return to the reservation rather than going to Newcastle, Wyo., with the sheriff.

Smith, known to the Indians as Eagle Feather, had attended the Carlisle Indian School. He had told the sheriff that he didn’t live in Newcastle and wasn’t going there. One posse member recalled that the sheriff told Smith he didn’t want trouble and wanted the Indians to come peacefully, but Smith replied, “I know the law, and I know your duty as well as you do, and what they expect of you, but you can’t take me.”[2]

Tensions grew over hunting rights

John Brennan, the U.S. Indian agent at the Pine Ridge Reservation, had granted passes to the Indians to leave the reservation for the purpose of “gathering herbs, roots and berries.” He gave passes to two parties in the fall of 1903: to William Brown on Sept. 30 and to Charles Smith on Oct. 20. This practice was not uncommon for Brennan, but he “made it a special point,” he noted later, “to caution all Indians going through Wyoming and Montana not to hunt while on their trip”[3] and instructed them to get permits from the proper officers if they did want to hunt.

Hunting had been an issue for many years. The disagreement about hunting rights occurred in part because the state of Wyoming’s laws had been interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896 in the Ward v. Race Horse case as superior to treaty agreements made previously by the U.S. government with the Indians. Concerns also arose prior to Race Horse that overkill of Wyoming’s game would discourage wealthy easterners who came to the state to hunt for sport. A lack of game thus could mean decreased state income.

Still another factor contributed to the increasing tensions when, in the early 1900s, rations provided by the U.S. government for Indians living on reservations were reduced.[4]

In October 1903, Sheriff Miller in Newcastle received word that Indians had been hunting illegally in southern Weston County and on the northern border of Converse County and that they had also been killing cattle. According to Weston County Clerk A.L. Putnam, “… so explicit and positive were these statements that, although no complaints had been filed by the stockmen, Sheriff Miller thought it his duty to look after the matter and put a stop to the lawbreaking and to protect the property of our citizens, which it was said was being destroyed.” The reports had come into the office between Oct. 20 and Oct. 22. The sheriff organized a posse of six that left Newcastle on Oct. 23. The sheriff could not leave until the next day and met the posse at a prearranged place.[5]

They found some Indians near Lance Creek, disarmed them, and three of the posse members took them to Newcastle. Another man joined the main posse, which continued for several days to Black Thunder Basin, where Indians had been reported, but they had gone before the posse arrived. The posse continued until they found the William Brown and Charles Smith parties on the Dry Fork of the Cheyenne River north of present Bill, Wyo. The Brown and Smith parties had met accidentally and were on their way back to the reservation. A broken wagon wheel, repaired travois-style with a pole that dragged the ground, left a trail that posse members followed.[6]

The lawmen arrived at the place where the Indians were camped at about noon. William Brown’s wife prepared a meal which posse men ate as they waited for Charles Smith to return. Later that afternoon, Smith came back and “had upon his horse … an antelope.”[7]

Miller tried to arrest them, but Smith refused to go to Newcastle, although others in the party were willing to. One posse member recalled that the sheriff read the arrest warrant to the Indians twice. The Indians broke camp, and although there was reportedly some confusion about whether the Indians were going to Newcastle, they instead went in the direction of the reservation. The sheriff and the posse decided not to follow at that time, but they warned the Indians they would be back. The lawmen then stayed at the Fiddleback Ranch about 20 miles away. The sheriff requested men from local ranches join the posse.[8]

Further complicating the matter, Charles Smith and Sheriff Miller reportedly disliked each other, having exchanged words in 1901 about illegal hunting.[9]

Bloodshed on Lightning Creek

On Oct. 31, 1903, the sheriff’s posse caught up with the Indians in the late afternoon at Lightning Creek. The Indians had traveled about 50 miles from the place where Sheriff Miller had first attempted arrest. Some of the Oglalas were traveling in wagons, and some were riding horses. They were in a procession about a quarter- to one-half mile long. “The approach of the sheriff and his posse, after they left the road and took up a dry gulch under the creek bank, was threatening and menacing,” according to a statement issued later by U.S. District Attorney for Wyoming Timothy Burke, implying that the posse had set up for an ambush.[10] Hope Clear, like many of the Indians that day, fled when the shooting started. Peter White Elk, the boy helping her, was shot in the head and killed instantly. Others killed were Sheriff Miller, who bled to death from a severed femoral artery about 30 minutes after the fight; Deputy Louis Falkenberg, who was shot in the neck and died instantly; Charles Smith, who died the next day; Black Kettle; and Gray Bear. Susie Smith, Charles’ wife, who was shot in the shoulder, died a few days later. Last Bear, wounded in the back, recovered.[11]

Miller had been moved to the nearby Mills Ranch cabin, where he died. Posse members guarded the cabin throughout the night, concerned that an attack might occur. The next morning, two posse members, James Davis and Ralph Hackney, took the bodies of Miller and Falkenberg to Newcastle. Other posse members returned to the scene of the fight to search the Indians’ wagons and found that several Indian women had built a fire and were tending the injured Charles Smith there. Smith was taken to the Mills cabin, and posse member Stephen Franklin took the women to Lusk where he sought a doctor. Smith died that night.[12]

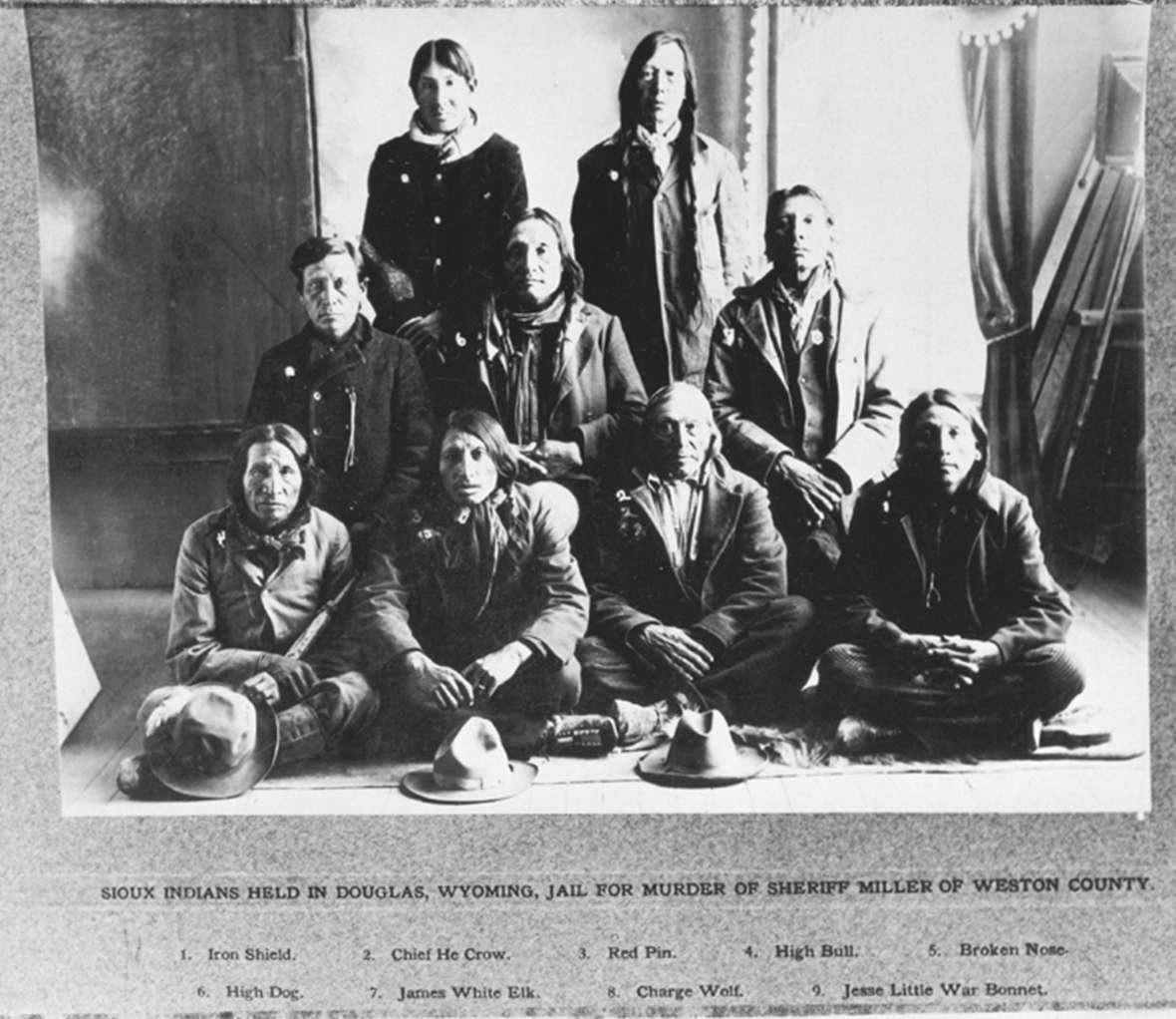

Another posse formed at Newcastle, this one organized by Crook County Sheriff Lee Mather, to capture the Indians who fled the scene. Some managed to go back to the reservation. Others were arrested in Edgemont, S.D., charged with murder, and these men were taken to Douglas, Wyo. The Converse County sheriff released the women and children to the custody of Indian Agent John R. Brennan. Brennan requested the release of the nine men, but Wyoming’s Acting Gov. Fenimore Chatterton refused. [13]

A preliminary hearing—the only legal proceeding in the case—was held in Douglas, Wyo., the county seat of Converse County, on Nov. 14, 1903, two weeks after the confrontation. Because of federal obligations to the tribes, U.S. District Attorney for Wyoming Timothy Burke represented the Oglalas in this state case. He did not call them to testify that day, but traveled to Pine Ridge later to take their statements because he could not find a place of appropriate secrecy to take their statements in Douglas, and because he believed that the case of the Weston County prosecutor, W.F. Mecum, was weak.[14]

|

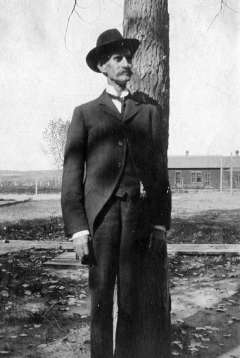

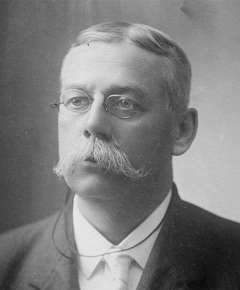

Acting Gov. Chatterton, along with Wyoming Congressman Frank Mondell, who was from Newcastle, and U.S. Sen. Francis E. Warren, supported the posse members and were dissatisfied with the results of the hearing. Charges against the Oglalas were dropped after the hearing, and they were released. No members of the posse were charged. Mondell and Warren used their influence to ensure a thorough investigation was made. They hoped the publicity would help highlight the state’s rights. In addition to the involvement of Burke and Special Indian Agent Charles S. McNichols, Maj. B.H. Cheever of the 6th Cavalry was sent by the War Department to attend the Douglas hearing, and the president’s secretary requested that the U.S. attorney general report to the cabinet at its next meeting.[15]

Burke’s conclusions

After examining the evidence, Burke issued a detailed report wherein he questioned Sheriff Miller’s legal jurisdiction to arrest the Indians. The sheriff’s warrant was issued in Weston County, Wyo., and the arrest was attempted in Converse County. Burke also wrote that the evidence did not show that the Indians were in violation of the law “unless the testimony is to be accepted that the Indian Smith had upon his horse, when he returned to his party at the time the sheriff first visited them, an antelope, which fact is denied by a number of the Indians in their evidence.”[16]

Burke determined that “the Indians were legally justified in resisting arrest under the conditions shown, but not to the extent of using deadly weapons, unless the sheriff’s posse first used their guns, and as that fact is in such hopeless uncertainty I can not believe that any thing is to be gained by further prosecution, for were proceedings to be had against either party the proper application of the rule of reasonable doubt would acquit the accused. A decision resulting from either race prejudice, supercilious generosity, or from a guess would but make a bad matter worse.”[17]

Indian Agent McNichols noted in his report that the trouble at Lightning Creek, resulting in part from a “local sentiment of race hatred, has stained a page in Wyoming’s history.”

Newspapers gave front-page space to the events, especially focusing on the fight and often referring to the Indians—in the vernacular of that era—as bucks, braves, squaws and redskins.

The weekly Newcastle Times on Oct. 30, 1903, carried an item about Miller and his posse searching for the Indians because reports had been received that “… several bands of Indians were scattered thru [sic] the Black Thunder basin, some seventy miles from Newcastle and were unlawfully killing antelope and cattle.” The article also stated, “One witness alone said he could under oath say that he had passed five carcasses of steers killed by gunshot wounds in the country where the Indians were hunting.”

The Wyoming Tribune, a daily newspaper, reported on the battle in its Nov. 2, 1903, issue. The report stated “… it is probable that in the event the governor fails to call out troops a small regiment of men will set out … tomorrow morning, all bent on avenging the death of the officers.” The newspaper also included information about a second battle wherein a posse formed to catch the Indians who fled the Lightning Creek fight and that ten Indians were killed. The next day, the newspaper explained there had been “great exaggeration” in the first report and also noted that the report of a second battle was “purely imaginary.”

The Newcastle Times in its Nov. 6 report, stated that “like a Custer [Sheriff Miller] held his ground. What matter were the odds two to one in the enemies’ favor; what matter were the bullets flying all around. He knew the peril and risk, and was only doing his duty as an officer when lo! a bullet struck him high up in the left hip severing the femoral artery and breaking the bone.” The Grand Encampment Herald carried “the true story … as told by Johnnie Owens, the celebrated scout and Indian fighter.”

A few days later, Cheyenne’s Wyoming Tribune carried an item from the Denver News with Buffalo Bill Cody’s opinion on the Wyoming incident and hunting rights. The famed western showman admitted he had “only glanced over the newspaper accounts, which are not all alike.” However, he believed that tribes “have a right to shoot game--not for the sake of slaughter, but for personal use. We must make allowance for the fact that they and their ancestors have lived largely by the chase, so some concession along that line should to my way of thinking, be granted them.” [18]

But Burke, as might be expected for an attorney, gave thoughtful consideration to the evidence and further, he interpreted the language of the treaties and referred to the 1896 Race Horse case. He explained, “… I do not find from a reading of the various treaties made with the Oglala Sioux that they had reserved any right to hunt off their reservation after the buffalo should cease to exist in ‘numbers as to justify the chase;’ their treaty of 1868 being merely that they should have the right to ‘hunt so long as the buffalo may range thereon in such numbers as to justify the chase’ being an entirely different provision from that made by the Crow and the Shoshone and other Indians, which are to the effect that they should have the right to hunt upon the unoccupied lands of the United States Government so long as the game should exist in sufficient quantities to authorize the chase. The latter provision as it appears in a number of treaties, however, has been construed against the Indians’ right, in violation of State law subsequently enacted, in the case of Ward, Sheriff, v. Race Horse(163 U.S. Rep. 504).”[19]

The Lightning Creek battle has been called the “last blood-spilling fight” between whites and American Indians in Wyoming. The conflict was not the last in the West, however. Armed skirmishes, many with bloodshed, continued intermittently until 1924.[20]

Resources

- “A Great Exaggeration of Fight with Indians.” Wyoming Tribune, Nov. 3, 1903. Accessed July 16, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- “American Indian Wars.” Wikipedia. Accessed April 20, 2018, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Indian_Wars#Last_conflicts.

- “Battle with Indians: Law Breaking Sioux Resist Arrest and Start a Fight, Two Whites and Five Bucks Dead.” Grand Encampment Herald, Nov. 6, 1903, 1. Accessed July 6, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Boyer, Lee R. “Conflict over Hunting Rights: Lightning Creek, 1903.” South Dakota History 23: 4. (301-320). Accessed April 20, 2018, at https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-23-4/conflict-over-hunting-rights-lightning-creek-1903/vol-23-no-4-conflict-over-hunting-rights.pdf.

- City of Douglas, Wyo. “Douglas Park Cemetery, A Walking Tour.” Accessed March 22, 2018, at https://www.cityofdouglas.org/DocumentCenter/View/43.

- “Indians.” Newcastle Times, Oct. 30, 1903, 1. Accessed July 18, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- “May Kill Game.” Wyoming Tribune, Nov. 15, 1903, 2. Accessed July 18, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Moss, Bill. Grandson of Lightning Creek battle eyewitness Foster Rogers. Email interview with author, July 12 and 17, 2018. Rogers herded sheep for Jake Mills at the time of the incident.

- Richardson, Ernest M. “Battle of Lightning Creek.” Montana the Magazine of Western History, (Summer 1960): 42-52.

- Tysdal, Bobbie Jo. Director, Anna Miller Museum, Newcastle, Wyo. Telephone interview with author. May 4, 2018. The museum has a collection with hundreds of papers and photographs of Sheriff Miller and his family.

- U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Indian Affairs. “Encounter Between Sioux Indians of the Pine Ridge Agency, S. Dak., and a Sheriff’s Posse of Wyoming.” 58th Cong. 2nd Session, 1903, S. Doc. 128.

- Timothy Burke’s Dec. 17, 1903, statement appears on pages 54-56; John Brennan’s statement appears on pp 30-31; Hope Clear’s testimony appears on pages 48-49; Charles McNichols’ letter appears on pages 11-16; Weston County, Wyo., Clerk Arthur Putnam Nov. 10, 1903, letter to Acting Gov. Fenimore Chatterton, pages 5-7; Hackney testimony, p. 77. Sheep herder and eyewitness Foster Rogers’ testimony appears on pages 94-95. A copy of the Wyoming Game and Fish Laws, 1903, appears on pages 98-109. The articles from the Newcastle Times and the Douglas Budget appear on pages 17-20.

- Van Pelt, Lori. “Willis Van Devanter: Cheyenne Lawyer and U.S. Supreme Court Justice.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed May 8, 2018, at /encyclopedia/willis-van-devanter-cheyenne-lawyer-and-us-supreme-court-justice.

- Voigt, Barton. “The Lightning Creek Fight.” Annals of Wyoming 49 (Spring 1977): 5-22. Accessed May 9, 2018, at https://archive.org/stream/annalsofwyom49121977wyom#page/n3/mode/2up.

- “Wyoming Becomes the Scene of a Bloody Conflict Between Sioux Indians and a Posse: Sioux Indians Kill a Wyoming Sheriff.” Wyoming Tribune, Nov. 2, 1903. Accessed July 16, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

Illustrations

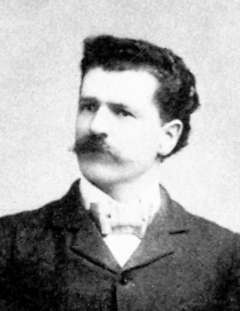

- The photos of the nine Oglala men, Timothy Burke and Frank Mondell are all from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks. Burke, who was U.S. attorney for Wyoming at the time of the Lightning Creek fight in 1903, was serving in Wyoming’s second Legislature about 10 years earlier when this photo was taken.

- The photo of Pine Ridge Indian Agent John Brennan is from the archives of the South Dakota Historical Society. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Sen. Francis E. Warren is from the Library of Congress via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Sheriff William Miller is from the Anna Miller Museum in Newcastle, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.

[1] U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Indian Affairs. “Encounter Between Sioux Indians of the Pine Ridge Agency, S. Dak., and a Sheriff’s Posse of Wyoming.” 58thCong. 2ndSession, 1903, S. Doc. 128. Clear’s testimony appears on pp 48-49. Letter of Special Indian Agent Charles S. McNichols to the U.S. Commissioner on Indian Affairs, 12-15, Putnam letter, 6. Referred to hereafter as S. Doc. 128.

[2] Eagle Feather was given the name Charles Smith while attending the Carlisle Indian School. Lee R. Boyer,“Conflict over Hunting Rights: Lightning Creek, 1903,” South Dakota History 23: 4, (301-320), 303. Accessed April 20, 2018, at https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-23-4/conflict-over-hunting-rights-lightning-creek-1903/vol-23-no-4-conflict-over-hunting-rights.pdf.

S. Doc. 128, testimony of R.B. Hackney, 77. On p. 13, Indian Agent McNichols states, “Both whites and Indians assert that the Indians would have quietly submitted to the arrest if it had not been for Smith.”

[3] S. Doc. 128, Pine Ridge Indian Agent John Brennan statement, pp. 30-31.

[4] Boyer, 312,314-316, 317-320, accessed April 20, 2018, at https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-23-4/conflict-over-hunting-rights-lightning-creek-1903/vol-23-no-4-conflict-over-hunting-rights.pdf. Boyer’s research provides some insight into the hunting matter. The Indians who traveled to Lightning Creek admitted they shot game in South Dakota, but not in Wyoming, in their testimony. Boyer explains, “In 1900, the Sioux of the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota had addressed a letter to the president of the United States to protest the latest in a long line of ration reductions. Such cuts, they contended, violated the 1876 Black Hills Agreement stipulating that the federal government would provide for the Sioux ‘until the Indians are able to support themselves.’”But the letter backfired, according to Boyer, and instead convinced government officials that the Indians had become self-sufficient. In June 1901, Indian Commissioner W.A. Jones directed six Sioux agencies to eliminate rations for those who could support themselves and those who were able but refused to work.

For more on the Race Horse case, see Boyer, 317-318, and also Lori Van Pelt,“Willis Van Devanter: Cheyenne Lawyer and U.S. Supreme Court Justice,” WyoHistory.org, accessed May 8, 2018, at /encyclopedia/willis-van-devanter-cheyenne-lawyer-and-us-supreme-court-justice.

[5] S. Doc. 128, Putnam letter to Wyoming Gov. Fenimore Chatterton, 6-7.

[6] S. Doc. 128, Putnam letter, 6, and John Brennan letter to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 8.

[7] S. Doc. 128, Timothy Burke, U.S. district attorney for Wyoming, statement, Dec. 17, 1903, 54-56. Burke reported that the Indians later denied this, but “… they admit having traded moccasins and articles of their own manufacture for untanned hides of deer and antelope.” This, according to Burke, would have been a misdemeanor, and he stated the Indians “probably ignorantly” violated that section of the Wyoming game law.

[8] S. Doc. 128, Charles S. McNichols, U.S. Department of Interior investigator, report, 11-16. In his report McNichols stated, “Both whites and Indians assert that the Indians would have quietly submitted to the arrest if it had not been for Smith.”

[9] Boyer, 303-304; Ernest M.Richardson, “Battle of Lightning Creek,” Montana the Magazine of Western History. Summer 1960: 42-52. Richardson later married the deceased sheriff’s daughter and believed Miller’s actions to have been heroic. According to Richardson, in 1901, Sheriff Miller received a complimentary letter from Wyoming Gov. DeForest Richards for his work in arresting and fining Indians who were hunting illegally. Miller’s arrest of those Indians had greatly angered Smith. Boyer explains that both an affidavit of a local rancher named Walter Sellers, provided four months after the Lightning Creek battle, and a letter from Weston County Attorney William F. Mecum to Acting Gov. Fenimore Chatterton, written about a week after the conflict, refer to the animosity between the two. According to Boyer, the Sellers affidavit states that Sheriff Miller had warned Charles Smith (Eagle Feather) not to hunt illegally, and Smith told Sheriff Miller “that antelope had no brands on, and he would kill them if he chose."

[10] S. Doc. 128, conclusions of U.S. District Attorney for Wyoming Timothy Burke, Dec. 17, 1903, 55.Burke continued, “ … but the result of the entire occurrence was not unnatural, for seldom do two bodies of armed men with cross purposes meet that shooting does not occur. The snapping from stepping on a dry twig or like occurrence under such circumstances may be the mistaken fact that leads to the fatal act.”

[11] Ibid., Brennan letter to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Nov. 17, 1903, 7-8. Brennan wrote,““The whole top of his head was blown off, indicating that the party who did the shooting was very close to the boy.” According to Indian Agent McNichols’ statement on page 15 of the Senate document, posse members said that Miller shouted warnings to the Indians three times and another posse member, Johnny Owens, warned them twice. Owens, McNichols explained, was a former sheriff and was referred to in the Newcastle Timesas a “noted Indian fighter.” McNichols also detailed the injuries. He asserted on page 14, “All reason and common sense is against the theory that the Indians began the firing.”

[12] Barton Voight. “The Lightning Creek Fight,” Annals of Wyoming 49 (Spring 1977), 11. S. Doc 128, McNichols, p. 13, said the Mills Ranch on Lightning Creek was where the posse met the posse members who had been sent ahead to locate the Indians.

[13] Ibid., 11, 15, 16.According to Voigt’s research, Chatterton sent a telegram on Nov. 5, 1903, to Brennan citing Race Horse. The decision in that case gave Wyoming the right to prosecution.

[14] Ibid., 18. Voight referred also to a Nov. 9, 1903, letter from Mecum to Chatterton that the posse had ambushed the Indians. The testimony of the Indians appears in S. Doc. 128, 32-54, and those sworn statements are dated Nov. 30, 1903. McNichols, in his report in S. Doc. 128, page 15, states that public opinion in Douglas was favorable to the Indians, while public sentiment in Newcastle was “strongly incensed against the Indians and very much worked up over the death of their sheriff, who was a popular official … .” He further stated, “The whites of the posse, with whom I was obliged to travel and stop for three days, were all drinking heavily, both on the road and at and after the hearing.”

[15] Voight, 15-16. Mondell “had a particular animosity toward Agent Brennan,” according to Voigt. The congressman attributed the battle to Brennan’s “bad management.” However, Indian Agent McNichols, S. Doc. 128, 15, thought Brennan had done an “admirable” job. See also Boyer, 309, regarding the charges. Richardson referred in 1960 to the report of the U.S. Senate investigation as “pure buncombe.” Voight points to racism as a factor in the conflict, but states on page 15 that contradictions in the testimony from both sides “in so many important details … suggest outright lying by one side or the other.”

[16] S. Doc. 128, Burke statement, p. 55. Burke wrote that Sheriff Miller, while “a good officer, a brave man, and one who intended to be right in all his actions” had been mistaken, but that “should not be attributed to any wrongful motive or purpose on his part.”

[17] Ibid, p. 55-56.”

[18] Newcastle Times, Oct. 30, 1903, accessed July 18, 2018 at http://newspapers.wyo.gov;Wyoming Tribune, Nov. 2, 1903, 1 and Nov. 3, 1903, 1, accessed July 18, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov. S. Doc. 128, the Nov. 6, 1903, Newcastle Times article appears on pages 17-20, and an article from the Nov. 18, 1903, Douglas Budget appears on p. 20. The Times quotation about Miller appears on p. 19. The Times,on the same page, reported that after the Converse County coroner arrived that the “four bucks” who had been killed were examined and buried. Also, Putnam, in his letter to Chatterton, p. 6, refers to the Indians as “bucks.” Grand Encampment Herald, Nov. 6, 1903, 1, accessed July 6, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov. Buffalo Bill quoted in Wyoming Tribune, Nov. 15, 1903, 2.

[19] S. Doc. 128, 55.

[20] Richardson, “Battle of Lightning Creek,” Montana the Magazine of Western History. Summer 1960: 42-52. Richardson was the first modern scholar to write about this encounter.