- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Flight of The Utes

The Flight of the Utes

The talking lasted 12 hours. Several times during the day, the Ute negotiators returned to their camp; the soldiers could do little but wait. Each time negotiations resumed, the Utes absolutely refused to return to the Utah reservation they’d left five months earlier.

It was early November 1906. Detachments of the Sixth and Tenth U.S. Cavalry, 1,000 troops in all, had caught up with the Utes on Powder River. Such a huge force was necessary, the War Department had decided, to “overawe” the Utes. To send a smaller force would have been to risk a fight. But no one knew what the outcome would be. Newspapers were in an uproar. Civil officials were frantic. The Utes were positive about one main thing: They would not go back.

Decades of land loss

At the beginning of the 19th century, Ute territory stretched from the front ranges of Colorado to the Utah deserts, from Taos and other pueblos in northern New Mexico to what’s now the Wyoming-Colorado border. After the United States’ war with Mexico, the Utes found their northwestern border invaded by Mormons; the U.S. Army built Fort Massachusetts in the San Luis valley near their southern border in 1855; gold discoveries at Pikes Peak in 1858 led to the collapse of their eastern border. Ute resistance to Mormon power in Utah Territory, meanwhile, led to the Walker War 1853 and the Black Hawk War of the 1860s, which led to more land lost and left a legacy of violence. President Lincoln established the entire Uinta Basin in northeastern Utah Territory, mostly rocky, barren land, as a future Ute reservation in 1861.

In 1868, Utes were pushed west of the Continental Divide in Colorado Territory. In 1872, gold was discovered in the San Juan Mountains near Colorado’s southwestern corner, and Utes were pushed north from there. This still left large stretches of land on Colorado’s western slope in control of several different Ute bands. Among these, along the White River in the northwestern part of the territory, was a band that came to be called the White River Utes. The government established an Indian agency there.

In 1878, Nathan Meeker, a journalist and social-religious visionary, was appointed agent. Meeker had founded the utopian Union Colony at present-day Greeley, Colo., in 1870 to show the world what communal Christianity combined with irrigated agriculture could do. On White River, he pressed the Utes to become Christians and farmers, to give up their horse herds and take up a settled life. They saw him as a tyrant, and revolted. In the fall of 1879 they killed Meeker and 10 other White men at the agency, and took Meeker’s wife, family and another family hostage for three weeks before releasing them.

Feeling the rising tension before he died, Meeker had sent for help from the Army. A detachment of about 200 troopers rode south from Fort Steele in Wyoming Territory. The same day the Utes killed Meeker, other White River Utes ambushed the soldiers, killed a dozen and kept the rest pinned down for four days. During that time the Fort Steele troops were joined by 35 troopers of the Ninth Cavalry, a Black regiment, which had been on duty 70 miles to the south; according to some reports, the Utes would not shoot at the Black soldiers. More reinforcements finally arrived from the north, and the Utes left.

Within three years, most Utes on the western slope of Colorado were moved to the Uintah and Ouray Reservation established earlier in the Uinta Basin south and east of Vernal, Utah Territory. The White River Utes were the last to have their Colorado lands taken, but some Whites thought that was not nearly punishment enough. Many soldiers looked on the band as enemies for another generation. “If the Utes had been thoroughly chastised after the Meeker massacre in 1879,” longtime Indian Bureau negotiator James McLaughlin wrote in 1910, “they would not be the irresponsible, shiftless and defiant people they are today.” Opinions like his seemed to be widespread in the Indian Bureau.

Allotment and departure

The government after the turn of the 20th century decided it was time to allot Ute lands “in severalty.” The land designated for reservations had been owned and used by all members of a tribe until 1887 when Congress passed the Dawes Act. The law mandated division of reservation lands into 80-acre plots for each head of household and 40 acres for other tribal members, which the allottees would eventually own outright. The rest of the land—usually the vast majority of the land on any reservation—was declared “surplus” and could then be thrown open for White settlement.

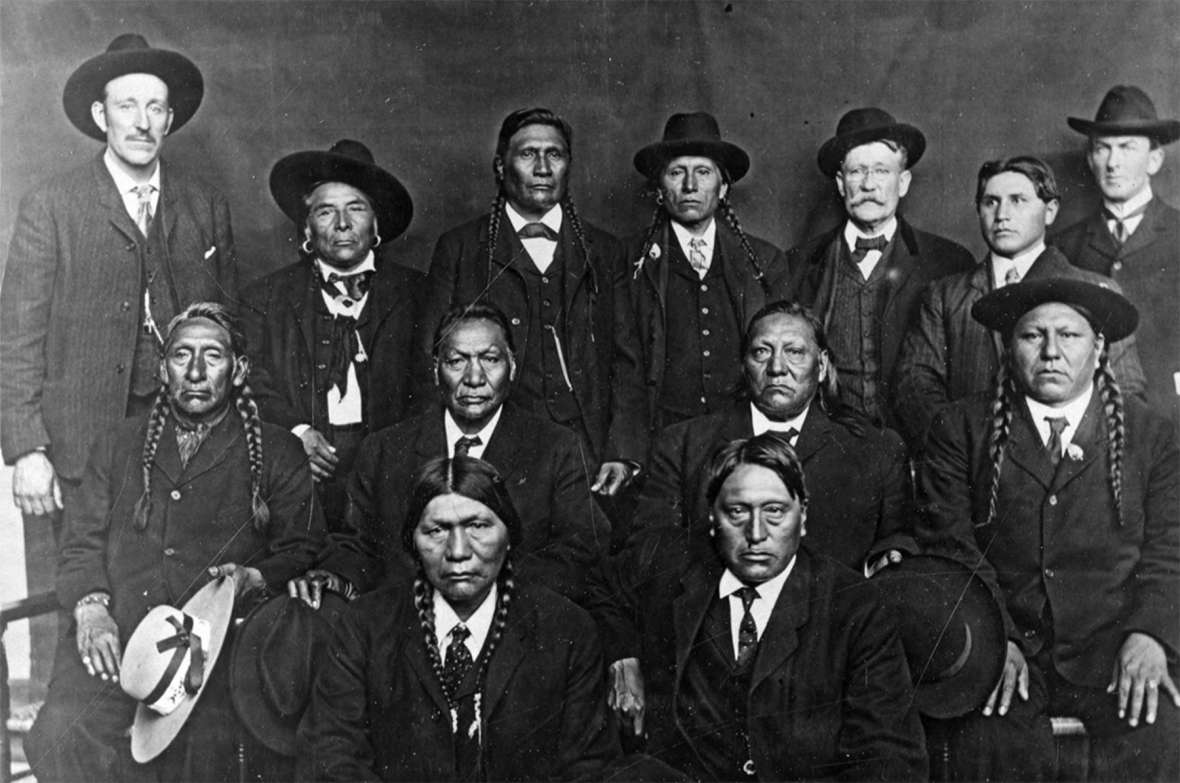

The White River Utes refused to cooperate. The agents of the Indian Bureau went ahead and allotted the lands without Indian input or consent. Bitter complaint followed from the Utes. A delegation traveled to Washington in 1905 but failed to make any headway. In a group, the White River Utes walked out of the talks. That year, White settlers began pouring into the newly opened land. Suddenly there was a lot more whiskey around, and there were fights and killings.

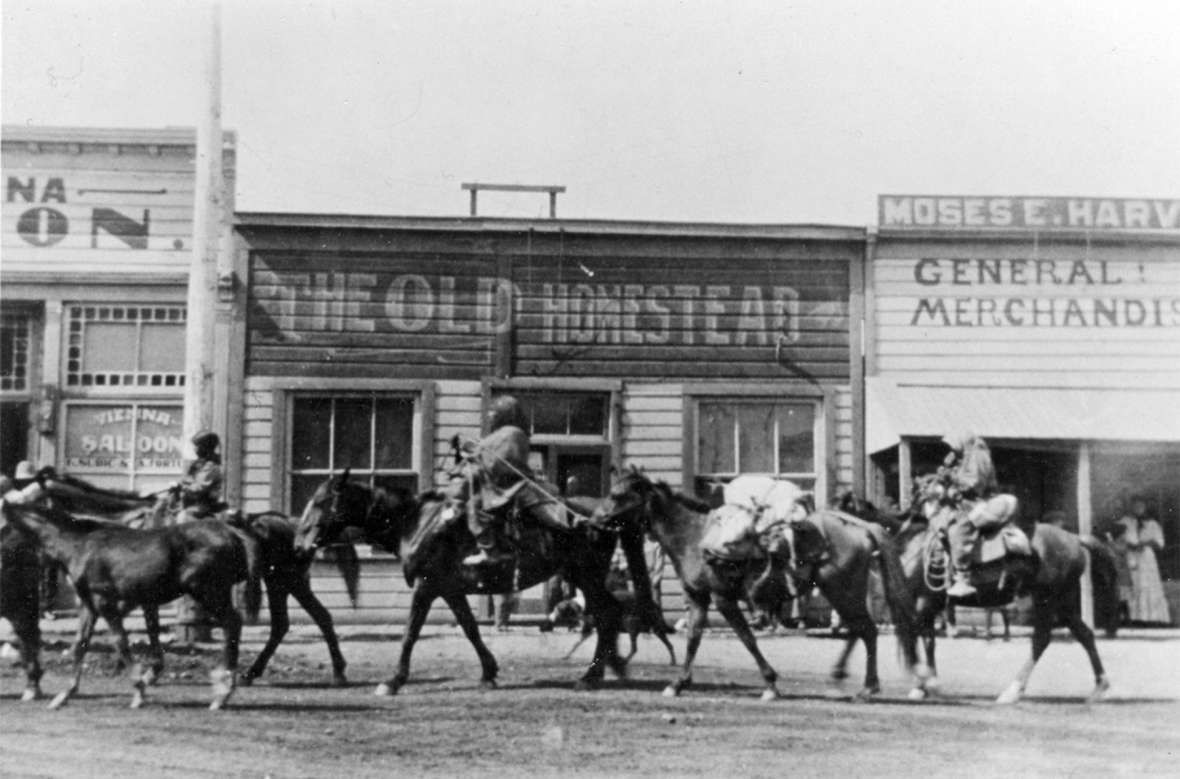

The following spring, hundreds of the Utes—mostly members of the White River band—left the reservation, and began moving north with a large horse herd. They traveled mostly with travois, and a few old wagons.

“Indian trouble of gigantic proportions is brewing,” the Vernal Express reported in late May 1906. The Utes, well armed and, according to the Express, ready to fight rather than return, were supposedly headed for “a great gathering of the Indians of all the West” on “one of the Northern Reservations.”

Moving north

In late June, the Wyoming Tribune in Cheyenne reported that a band of Utes from the Uintah Reservation had been seen camped on Willow Creek in remote Brown’s Park in the far northwestern corner of Colorado. A civil engineer, Reed Myer, said they were outwardly friendly to Whites, that they were planning “an alliance with some other tribe, probably Crows” in Montana, but that they were holding “war dances and secretly intended going on the war path.”

The Tribune reported Aug. 6 that the Utes—“seven hundred of the red devils—” had been seen passing recently through Whiskey Gap, in central Wyoming about 40 miles north of Rawlins. The Utes “were killing all the game in the country” and “are not too particular as to ranchmen’s cattle . . .”

By mid-August they were camped for miles along the North Platte River upstream from Douglas, Wyo., and there they seemed ready to pause for a while.

Pointing fingers

White authorities were caught completely off guard. The Indian Bureau directed White River Utes agent C.G. Hall to follow the band into and across Wyoming; telegram after telegram from Washington directed him to persuade the Utes to stop roaming. The agent at the Pine Ridge Sioux Reservation in South Dakota wired Washington in late July that a few Utes had already reached there and been ordered to leave, the agent telling them they had no right to stay. On Aug. 11 Hall reported the main band had caused “no depredations or unlawful acts.”

News reports, meanwhile, careened from calm to calamity. At Douglas, Converse County sheriff Messenger told the Laramie Semi-Weekly Boomerang that “[s]ensational reports” that the Utes were in “an ugly mood . . .are erroneous.” They had been steadily purchasing supplies in Douglas, sometimes refusing to pay for flour and sometimes choosing to “treat white people with insolence,” Messenger said. Generally there had been no trouble, but local Whites were fearing it wouldn’t take much to “incite a repetition of the Meeker massacre,” according to the Boomerang.

Messenger added that he had not called for state troops—National Guard—or national troops—U.S. Army regulars.

On Aug. 24, Hall, the Indian agent, wired Washington that the Utes were “absolutely immovable.” He added, “as allottees and therefore citizens, [the Utes] insisted on their freedom to go where they pleased,” but had threatened depredations if and when their supplies ran out.

Indian citizenship was a sticky question that reveals profound contradictions and uncertainties in the attitudes of White society at the time. The Dawes Act provided that allottees would become U.S. citizens. So what did that mean for these Utes, whose names just recently had been attached to individual allotments, even if they hadn’t participated in the process? Further complicating the question, Congress in 1905 set up a system that deferred final transfer of land ownership to allottees by 25 years. So did that mean that Indians who’d gotten allotments before that date were citizens, while the later ones were not yet citizens? No one knew; there were no precedents. Behind it all was the tacit fear that if they were citizens, there was no legal way for the Army to round them up as long as they committed no crimes.

On Aug. 25, Wyoming Gov. B.B. Brooks wired the Indian Bureau that the Utes had left the Douglas area, that he feared trouble, and asked the bureau to remove the band from Wyoming. Again, Hall was instructed to go talk with the Utes, and to impress on them that citizenship meant “burdens as well as responsibilities.” This time he talked with them for five full days, according to one news report, without result.

On Aug. 27, the Indian Bureau wired back to the governor that as long as the Utes were “peaceable and do not threaten hostility,” it wasn’t a federal matter. Unhelpfully, the commissioner of Indian affairs added, “[m]oral suasion has been used to little apparent effect, and therefore it was a matter “for local authorities.”

Hall, meanwhile, asked the Indian Bureau to send its best-known persuader and negotiator, James McLaughlin, to talk to the Utes. Wyoming’s lone Congressman, Republican Frank Mondell, wrote Washington that the Utes were “a constant source of irritation and menace to the settlers. . .” The bureau replied that McLaughlin had been sent in.

Enter McLaughlin

McLaughlin by this time had had a long career with the bureau. Beginning in 1876, he had served at Devils Lake, an agency to the Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota, and in 1881 was moved to the Standing Rock agency on what then was still the Great Sioux Reservation before it was divided into smaller parcels. In December 1890, during the ghost dance scare, McLaughlin ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull at Standing Rock, setting off a series of events that led to Sitting Bull’s death and the massacre two weeks later of hundreds of Miniconjou Lakota Sioux by U.S. troops at Wounded Knee.

In 1895, McLaughlin was promoted to the rank of inspector in the bureau. Often, he was tapped to handle difficult negotiations, especially with tribes of the northern plains. In 1896, he persuaded the cash-strapped Shoshones and Arapahos of Wyoming to sell the Big Horn hot springs—at present Thermopolis—and in 1904 he persuaded them to sell more than half the reservation that remained.

He knew the White River Utes as he had also been involved in the allotment negotiations with them. He believed he loved Indians, but his true attitudes were judgmental and paternalistic. In 1910, he published a memoir, My Friend the Indian.

In that book, he tells how he arrived in Casper, Wyo. on Aug. 25, took a train to Douglas, hired a guide named Tracy who did not know the country and in a rented wagon drove north and east of Douglas on a 100-mile loop that turned up nothing. Next step was a train trip via Nebraska to Newcastle, Wyo., and then a two-day journey west and north; finally he and his driver, a deputy game warden, found the Utes camped near the headwaters of Black Thunder Creek, which would place them on the prairie 10 or so miles east of what’s now the town of Wright.

He counted around 400 people in the band. “They were a sullen lot,” he writes, “though the few I knew treated me courteously enough.” None were “personally offensive,” though none offered any hospitality, either. “It was hopeless from the first,” he judged. In council, Ute leaders Soccioff, Red Cap and Appah made speeches saying they’d be happy if the government went ahead and gave their allotments to local Whites, as they’d already lost the rest of the reservation. Each said he would rather die than return to Utah.

But McLaughlin was able to persuade 61 of the Utes—in a separate meeting—to go back to Utah. Fifteen of these “vanished during the night.” Still, that left 46, who left the main band and returned—about an eighth of the entire band. “It was an achievement,” he wrote “to which I look back with some pride as being the most effective demonstration of Indian diplomacy that I have been able to exercise . . .”

Rumors of War

On Oct. 11, a sheep rancher wired the Indian Bureau that Utes were robbing sheep camps, killing game and cattle and that he feared trouble. On Oct. 14, Gov. Brooks wired Washington that the band had reached Gillette, Wyo., where they were “drinking, insulting and stealing, and had defied local police,” according to the Bureau’s report. (They were also buying a lot of flour and other supplies in the stores.) Brooks requested “prompt action.”

The Utes camped on Little Powder River, about 40 miles north of Gillette. The Indian Bureau wired back to the governor: Are you asking for troops? Yes, was the reply. President Theodore Roosevelt directed the War Department to handle it; the secretary of War directed Maj.-Gen. Greely to send cavalry to “command the invaders” to go back. The president directed the Utes be “firmly but tactfully dealt with.”

The closest soldiers, and the first ready to go were two troops of the Tenth Cavalry—Black buffalo soldiers garrisoned at Fort Robinson in northwestern Nebraska. They arrived in Gillette the last week in October. On Sunday the 21st, according to the Cheyenne Daily Leader, their officer, Capt. Carter Johnson, rode all night with only “an orderly and a single scout,” reaching the Ute camp on Little Powder late Monday. “A pow-wow followed,” the paper reported. Johnson was unable to convince them to return.

Newspaper accounts at this point begin to overheat, showing a lot about White fears. The band veered northwest, apparently heading for the main stem of Powder River and the Northern Cheyenne Reservation. Utes killed “all but one” of a herd of 250 antelope on the Little Powder, settlers reported. Troops of the Tenth captured 50 Indian ponies, the Wind River Mountaineer reported, after which armed Utes surrounded the herd and with revolver shots tried to stampede them; the troops supposedly killed five ponies to stop the stampede. Various “wandering bands” of Crows or Cheyennes, whose reservations were nearby, just north of the Montana line, were reported north and east of Sheridan. A report from, for some reason, St. Paul, Minn., said that five cowboys had been killed and a beef herd raided by the Utes. Another from Omaha reported a “clash” in which Utes opened fire on troops, killing one and wounding more; the cavalry supposedly returned fire and killed three Utes before the rest fled.

The Sheridan Post feared the Utes would link up with the Cheyennes. “The Cheyennes are bad fighters,” the Postremembered, recalling that it was they who were deported to Oklahoma “at one time” (it was 1877) but refused to stay, defied the Army and walked back home. The Thermopolis Record was “quite certain” the Utes would join the Cheyennes, who “can muster 500 fighting men;” they would be hard on any “green troops” sent to chase them. The Utes, meanwhile, had broken up into small bands, the Record continued, and “troops are at a loss” how to find them.

None of these claims were true. The Gillette News, at least, was sympathetic, writing that the Utes had done nothing unlawful, were American citizens, had received “many letters of good behavior from citizens all along the line of march through Wyoming” and had left their reservation because to stay there would have been to starve.

The Utes camped on Powder River, a short way north of the Montana line. By now, four troops of the Tenth Cavalry, six troops of the Sixth from Fort Meade near Sturgis, S.D. and two troops of infantry from Fort McKinney at Sheridan were approaching—about 1,000 soldiers in all. Early on the day before they arrived, however, a news photographer made his way into the Ute camp, and began making pictures as fast as he could.

Tolman’s pictures and the Big Talk

T.W. Tolman’s photographs, together with his captions and comments, took up one page in each of two installments of Collier’s Weekly, a national magazine of general interest, in November. He wrote that he and a few others, unnamed, arrived at the camp about daylight, unsure of how they’d be received. Quickly it became clear “there was an undercurrent of distrust,” but he acted as if everything was fine and kept taking pictures. The photos in the first installment show women drying meat and dressing deer hides, an old man named Red Crow in front of his tipi, and a landscape of widely spaced tipis stretching up into a draw.

A cowboy came by and said the soldiers were only 20 miles away. It was time to leave. Tolman’s party mounted and “rode leisurely out of camp.” Soon, a young Ute man overtook them, riding fast, passed them, turned, came back—and in broken English, made it clear that ranch families in the district would not be safe if the soldiers came. “He said: ’You tell soldiers,’ and then he pointed up the trail and said: ‘Now you go’—and we did so.”

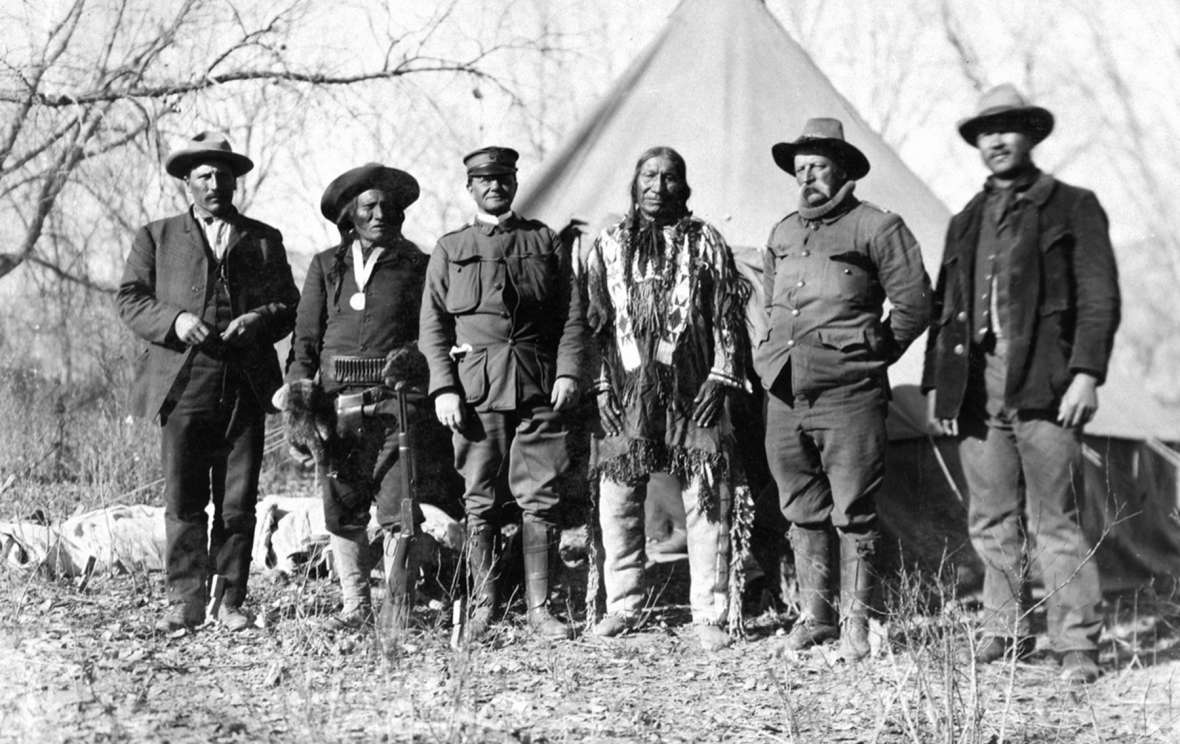

The soldiers did come, the Utes did not attack any ranches and Tolman returned to take a lot more photographs of Utes. These included pictures of troops; their horses and supply wagons; interpreters; Tenth Cavalry Capt. Johnson and other officers; two aging, pro-government Oglala Sioux veterans of the Indian Wars—Woman’s Dress and American Horse—who came with the Sixth Cavalry to help with the negotiations; Sioux interpreters Pete Shangreau and Frank Goings, and many others.

Tolman called it The Big Talk. It lasted 12 hours. This was Nov. 1. “Utes Will Go To Fort Meade,” the Cheyenne Daily Leader headlined on Nov. 4. They agreed to go with the Sixth Cavalry to Fort Meade and stay there for the winter on the promise that their leaders would be allowed to travel to Washington, D.C. and lay out their grievances before the commissioner of Indian affairs, the secretary of Interior and the president. They had “great faith” in Roosevelt, In The Leader reported, and called him “Mighty Hunter.”

The return

The Utes camped for the winter on the military reservation at Fort Meade, where the Army fed them. A delegation did travel Washington in January 1907. They met with President Roosevelt and again made clear they would not return to Utah. He expressed sympathy, but stressed also that they must work if they planned to stay in South Dakota. In March, Capt. Carter Johnson of the Tenth Cavalry, who also had earlier been their agent in Utah, brought them a message from the president: They must return. The news caused “great excitement in the Indian camp,” the Crook County Monitorreported, “and the reds were very indignant over the order.” Red Cap said he would not go back without a fight.

But Johnson had another plan in mind. On a visit to Washington, D.C. that same month he encountered Thomas Downs, agent for the Cheyenne River Sioux. A large, partly wooded and well-watered grazing lease in the northwestern quarter of that reservation, near the confluence of Thunder Butte Creek and the Moreau River, was due to expire June 1, Johnson learned. Perhaps the Utes could be settled there. The rent could be paid out of the annual annuities the Utes were due as part of the government’s treaty obligations. In April, the Cheyenne River Sioux agreed to a five-year lease. The Utes moved there in June.

The Army continued to provide rations. But the Utes were not receiving the warm welcome from the Sioux that they had expected; the Sioux had troubles of their own. Downs was not pleased with the situation either; he reported to Washington that just as he’d been improving his own relations with the Sioux, resistance among the Utes had complicated things. Washington instructed him to cut the Utes’ rations in half.

And how would they support themselves? The men must be willing to work, the government declared. Work was offered all of them on the Santa Fe Railroad, together with free housing for their families. But that was too far away, the Utes responded—and what would become of their horses? Sell the horses, said the government. This the Utes were not willing to do. They refused as well to go to work on the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul railroad, only 100 miles away and close enough, the government argued, that parents would have been able to visit their children enrolled in an Indian boarding school in Rapid City.

In October 1907, with winter approaching, disputes arose over the amount of rations the Utes had been promised, the question of work and of whether their children would be required to go to the agency schools—or to boarding schools, which their parents especially feared. At Downs’s request, the government sent in cavalry to protect the white employees at the agency. Johnson again visited, and as the Utes by now trusted him, the crisis passed.

But it was becoming clear the Utes’ time was about up. “It seemed to me,” Francis Leupp, the commissioner of Indian affairs, wrote in his report that year, “that we had reached a crisis in their affairs where the only thing to do was to keep them faced squarely with the alternative which had been held out to them from the beginning—the same alternative faced by every race and color in this country: since work and wages had been offered them, they must either earn their bread or go without it . . .”

“I neither attempted nor advised any measure of coercion,” he added.

In the winter of 1907-1908, with troops still nearby, some Ute men took work on the Missouri River and Northwestern Railway and earned wages, but the company went broke and left some wages unpaid. Others took odd jobs at the Rapid City Indian School—where their children could attend and were fed and clothed while there.

By January 1908, even the militants were beginning to relent. The Bureau was ready to spend nearly $10,000 to pay for the trip back to the shrinking reservation—for harnesses, wagons and draft horses, and for camping fees along the way. Capt. Johnson accompanied them, along with 10 buffalo soldiers from the Tenth. He wired Washington that there were 360 Indians in the band. They left Fort Robinson in early August and were back on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in October—1,000 miles in 101 days.

Aftermath

Ten Utes died en route and more than 40 died in barracks, the Vernal Express reported Oct. 16, 1908; it’s unclear if the Express meant barracks at Fort Meade in South Dakota or Fort Duchesne in Utah. “[B]ut as soon as they were given outdoor life,” the report added cheerfully, “they became healthy.” Fifty people out of a group that small, however, is a huge death toll.

Most written accounts of the time—the newspapers, the Indian Bureau reports and correspondence and McLaughlin’s memoir—are admittedly one-sided. But though they tell us very little about the perspective of the Utes, they show a great deal about conflicting fears, rage and guilt in White society that were aroused.

This much is clear: A band of a few hundred Utes had just completed a thirty-month act of nonviolent civil disobedience. They left Utah because they saw allotment as an existential threat to their culture and their economy, which it was. The events are a clear demonstration of the failures of the reservation system. The Utes were looking for a place where they could live as they wished and not be forced to farm. On the march—Tolman’s photos show this—they appear to have been doing just that. They returned because the government left them no alternative.

A centennial journey

In May 2006, a group of 30 Ute tribal members traveled from the Uintah-Ouray reservation to South Dakota to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the events of 1906. There, they visited Fort Meade and the Thunder Butte area on the Cheyenne River reservation. Nine graves of Utes who had died there 100 years earlier had been found just two days before, along with signs of several other Ute graves, the Vernal Express reported.

Maria Cuch, one of the Utes who made the trip, said she learned from Sioux tribal records in South Dakota that there was more to the story. “I knew that these people cared for ours, not just in historical times but this day. The care they took, they provided us with food, sage that had been cared for, blankets and their company.”

Loya Arrum, who also made the trip, told the newspaper, “There is a lot of heartache and sadness. A lot of people said they felt a weight lifted because some of the unknown and uncertainty is gone, but the tribe needs to go through a healing process.”

“Those of us that went are glad,” she said after returning to Utah. “We are happy because we didn’t know what had become of our people. We are still in the discovery stage, but we know where they had been and where they are.”

There are now more than 2,000 enrolled members of the Ute tribe of the Uintah-Ouray reservation, also called the Northern Ute tribe, which includes descendants of the White River Utes and other bands. More than half of those members still live on the reservation their ancestors fled in 1906. There are two other Ute reservations: the Southern Ute tribe, based in Ignacio, Colo., and the Ute Mountain Ute tribe, based in Tawaoc, Colo., with lands in southwestern Colorado, northwestern New Mexico and Utah.

(Special thanks to Robert Henning, Angela Beenken and the staff of the Campbell County Rockpile Museum, for making available substantial photo and other resources for this article. And thanks to Wyoming Humanities for support which made it possible.)

Resources

Newspapers

- Big Horn County News, Oct. 6, 1906

- Buffalo Bulletin June 28, 1906; Nov. 1, 1906

- Cheyenne Daily Leader, Oct. 3, 1906; Oct. 27, 1906; Oct. 30, 1906; Nov. 2, 1906; Nov. 4, 1906

- Crook County Monitor, March 15, 1907

- Gillette News, Oct. 16, 1906

- Laramie Republican, Nov. 1, 1906

- [Laramie] Semi-Weekly Boomerang, Aug. 23, 1906; March 18, 1907

- Rock Springs Miner, Aug. 25, 1906

- The [Sheridan] Enterprise, Nov. 6, 1906; Nov. 9, 1906

- Sheridan Post, Oct. 26, 1906; Nov. 9, 1906; Nov. 30, 1906

- Thermopolis Record, Nov. 3, 1906

- Vernal Express, May 10, 2006.

- Wind River Mountaineer, Nov. 2, 1906

- Wyoming Tribune June 25, 1906; Aug. 6, 1906; Aug. 23, 1906; Aug. 29, 1906; Oct. 25, 1906; Oct. 27, 1906; Oct. 29, 1906; Oct. 31, 1906

- All newspapers accessed via the Wyoming Digital Newspaper Collection, except for the Vernal Express, from the collections of the Campbell County Rockpile Museum, accessed originally via Newspapers.com.

Other primary sources

- McLaughlin, James, My Friend the Indian Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989: 372-387; first published 1910.

- Shangreau Interview, April 30, 1907, Richard E. Jensen (ed.), The Indian Interviews of Eli S. Ricker, 1903–1919 Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005: 361-366.

- Tolman, T. W., “The Unquiet Utes,” Collier’s Weekly, Nov. 17, 1906, 12, accessed Feb. 3, 2021 at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000068357757&view=1up&seq=204&q1=Ute.

- ____________., “Calming the Utes,” Collier’s Weekly, Nov. 24, 1906, 14, accessed Feb. 3, 2021 at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000068357757&view=1up&seq=236&q1=Ute.

- United States Office of Indian Affairs. Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1907): 125-131, accessed Feb. 3, 2021 at https://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?type=goto&id=History.AnnRep07&isize=M&submit=Go+to+page&page=125.

- _____________________________________. Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908): 118-121, accessed Feb. 3, 2021 at https://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?type=goto&id=History.AnnRep08&isize=M&submit=Go+to+page&page=118.

Secondary sources

- Laudenschlager, David D. “The Utes in South Dakota, 1906-1908.” South Dakota History Vol. 9, No. 3 (1979): 233-247, accessed Feb. 11, 2021 at https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-9-3/the-utes-in-south-dakota-1906-1908/vol-09-no-3-the-utes-in-south-dakota-1906-1908.pdf.

- Nichols, Jeffrey D. “The Ute Trek to South Dakota in 1906 Ended in Disappointment.” History to Go, Utah State Division of History, accessed Feb. 7, 2021 at https://historytogo.utah.gov/ute-trek/.

- O’Neil, Floyd A. “An Anguished Odyssey: The Flight of the Utes, 1906-1908.” Utah Historical Quarterly 36 (1968): 315-327, accessed Feb. 11, 2021 at https://issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume36_1968_number4/s/104768.

Illustrations

- The photos of the White River Utes’ 1905 delegation to Washington and of Red Cap and his family in South Dakota are from the digital collections at the Utah State Historical Society. Used with thanks.

- The 1906 photo of Utes in Rock Springs is from the collections of the Sweetwater County Historical Museum in Green River, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.

- The T.W. Tolman photo of the buffalo soldiers of the Tenth Cavalry is from the Northwest Museum of Art & Culture/Eastern Washington State Historical Society in Spokane, Wash., image number L94-71.29. Used with permission and thanks.

- The rest of the photos, all by Collier’s photographer T.W. Tolman, are from the collections of the Campbell County Rockpile Museum in Gillette, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks. While Tolman was in Wyoming, he stayed with TJ Ranch foreman Harve Swartz, and later sent Swartz a large selection of the photos in thanks for his hospitality, loan of a saddle horse and help getting him to the Ute campsite. Those photos came to the museum courtesy of the Tarver family, present owners of the ranch.