![Camp Scene from the Hayden survey] black and white landscape of open plains and a creek with a teepee. Ferdinand V. Hayden and an unidentified American Indian sit and stand in front, respectively.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2026-01/Camp%20scene_Hayden%20survey_ah003766.jpg?itok=viL_iTIM)

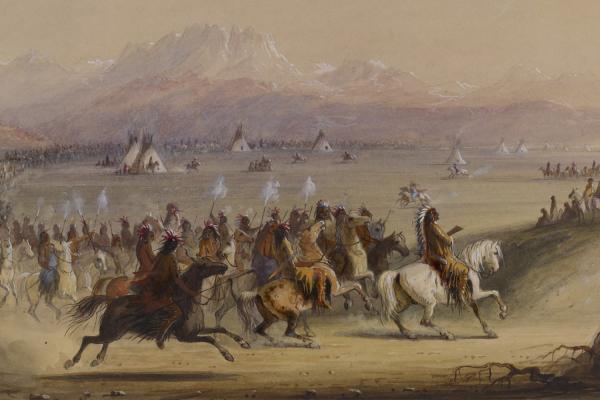

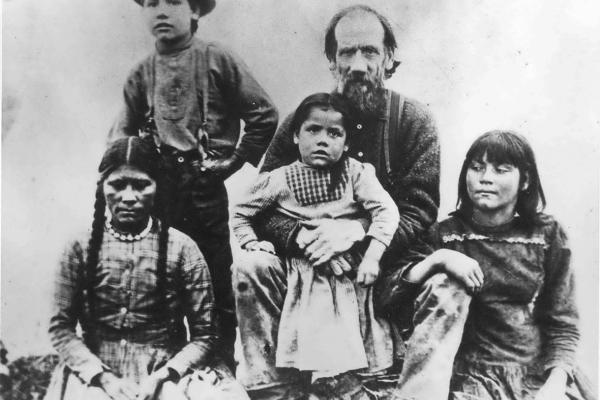

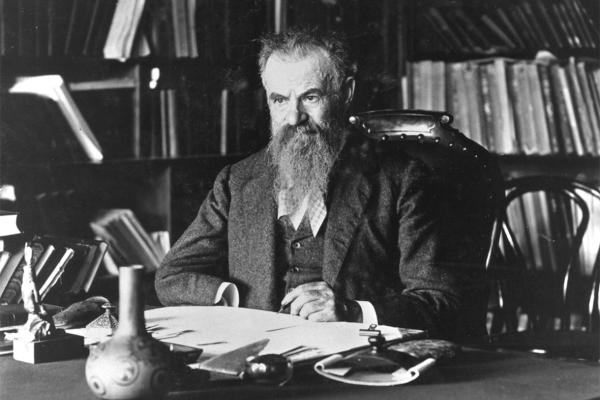

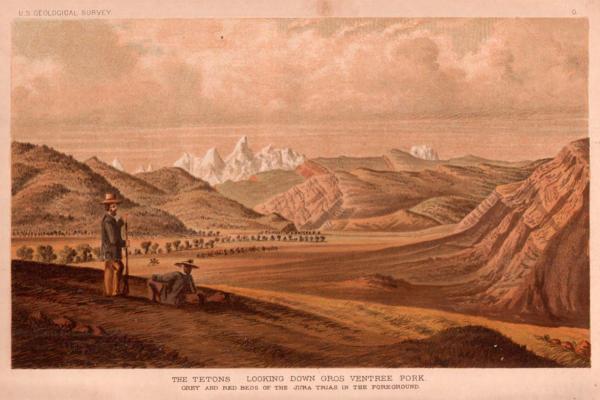

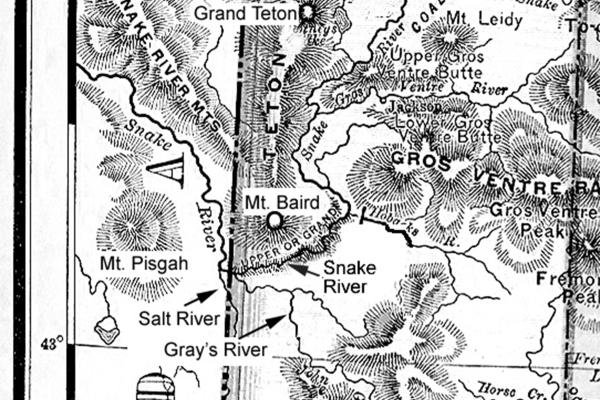

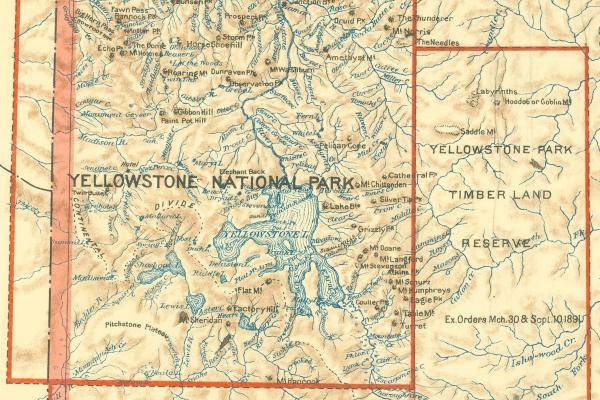

Before European and American explorers arrived, this region had long been home to the Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, Crow, Cheyenne, Lakota, and other Indigenous nations whose histories stretched back thousands of years. For more than a century, trappers, explorers, surveyors, prospectors, and scientists traveled routes established by Indigenous peoples, mapping terrain, documenting resources, and bringing national attention to Wyoming’s natural wonders. Their work ranged from fur trading and military surveying to scientific expeditions and photography that shaped how Americans understood the West.

The legacy of exploration reflects both achievement and displacement. While explorers expanded geographic knowledge and opened economic opportunities, their work facilitated the transformation of Indigenous homelands into U.S. territory, leading to profound disruption of Native communities. Understanding both the genuine accomplishments of exploration and mapping alongside their costs provides essential context for Wyoming’s development.