- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Wyoming Adventures of Captain Bonneville

The Wyoming Adventures of Captain Bonneville

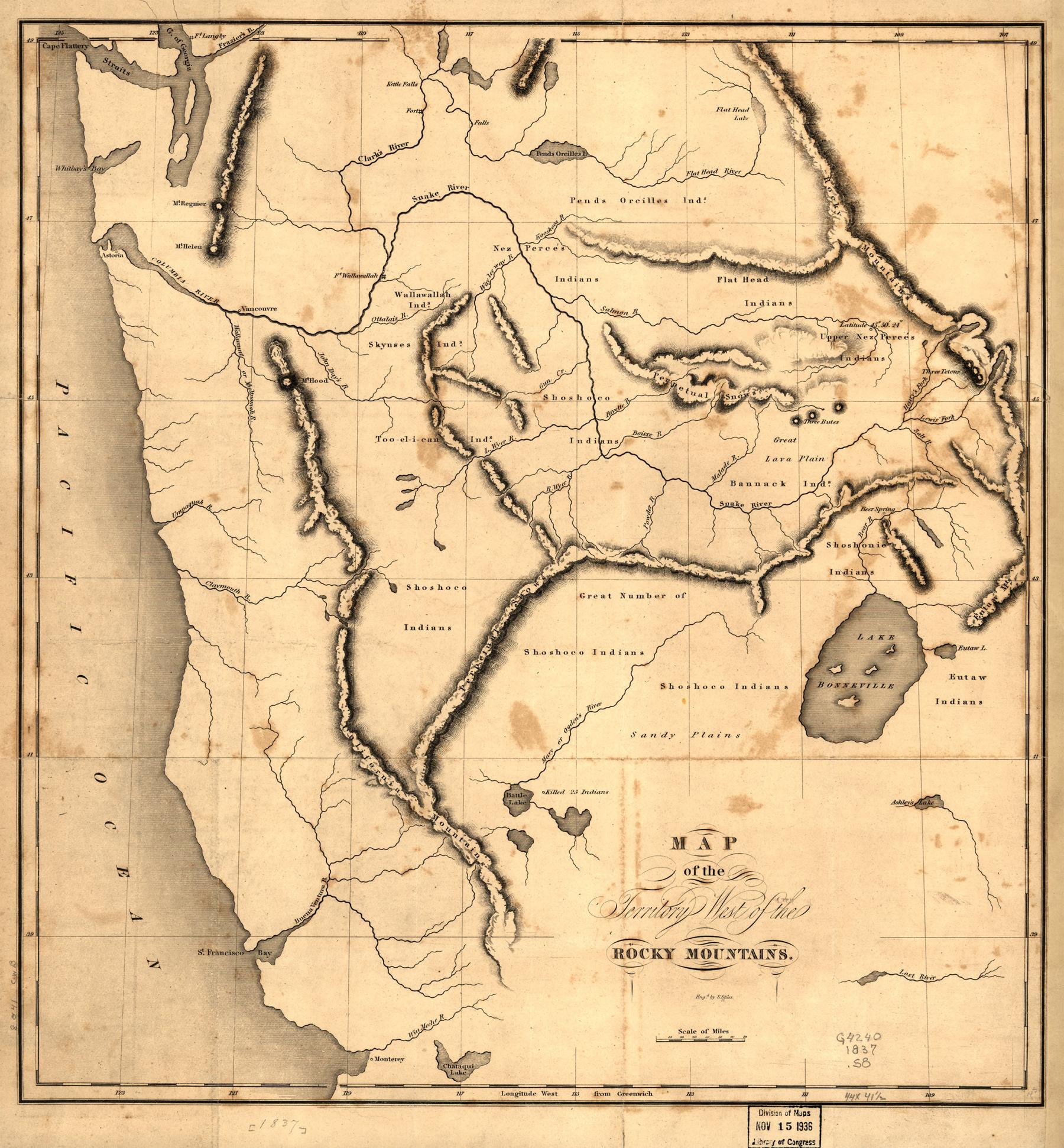

In the spring of 1832, Capt. Benjamin Bonneville of the U.S. Army outfitted a privately funded wagon train to the Rocky Mountains and beyond. Promoted as a fur-trading venture and backed by fur-trade financiers John Jacob Astor and Alfred Seton, the real purpose of this trip has been debated ever since. Although the Army granted Bonneville’s request for a yearlong leave, it stressed that his trip was unofficial. Still, the expectations of what the captain was to observe and record as stipulated in his leave authorization make it clear that the army wanted intel in exchange.

Image

A Lasting Mystery

Leaving Independence, Missouri at the end of April with 121 men and 20 wagons, Bonneville hoped to reach that year’s mountain rendezvous held in July at Pierre’s Hole in present Idaho, just west of the Tetons. Making his way to Wyoming’s rivers—the Laramie, North Platte and up the Sweetwater—and accompanied by seasoned mountain men Joseph R. Walker and Michel S. Cerré, the adventurous captain failed to make the gathering. But though he did not reach it in time, Bonneville accomplished something no one else before him had tried: crossing the Continental Divide, at South Pass on what we now know as the Oregon Trail—with wagons. Two years earlier, mountain man William Sublette led a wagon caravan to the eastern edge of the Wind River Range but reverted to pack horses for trading trips to the rendezvous. It was Bonneville’s expedition that paved the way for future wagon travel through the mountains.

By demonstrating that wheeled vehicles could cross the Rockies, Bonneville’s name would be indelibly imprinted in the histories of western exploration and settlement, and on several geographic landmarks (e.g., Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah; Mount Bonneville, Wyo.). But his activities in Wyoming and further west became even better known by the publication of a popular tale about his western travels.

Early western explorers and visitors often kept journals or diaries recording where they went, what they did and what they saw. Their writings remain indispensable for anyone interested in the history of the early American West. Bonneville kept a such a journal which is now lost.

After finally returning from his expedition, in 1835, he used it to try writing an account of his journey. Unable to find a willing publisher, he sold his journal and writings to Washington Irving (of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow fame) who soon wrote a romanticized and lasting story of the explorer’s western adventures, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville. Much of what is known about Bonneville’s time in Wyoming is based on Irving’s work.

But there is one report Bonneville submitted to the army after his first year in Wyoming that Irving probably did not have. It too went missing—but eventually turned up in the 1920s among misfiled Army documents. That “lost report” revealed much about what historian Anne Abel-Henderson, who was involved in discovering it, described as Bonneville’s “ulterior motive” for visiting the far west.

Bonneville’s Beginnings

Image

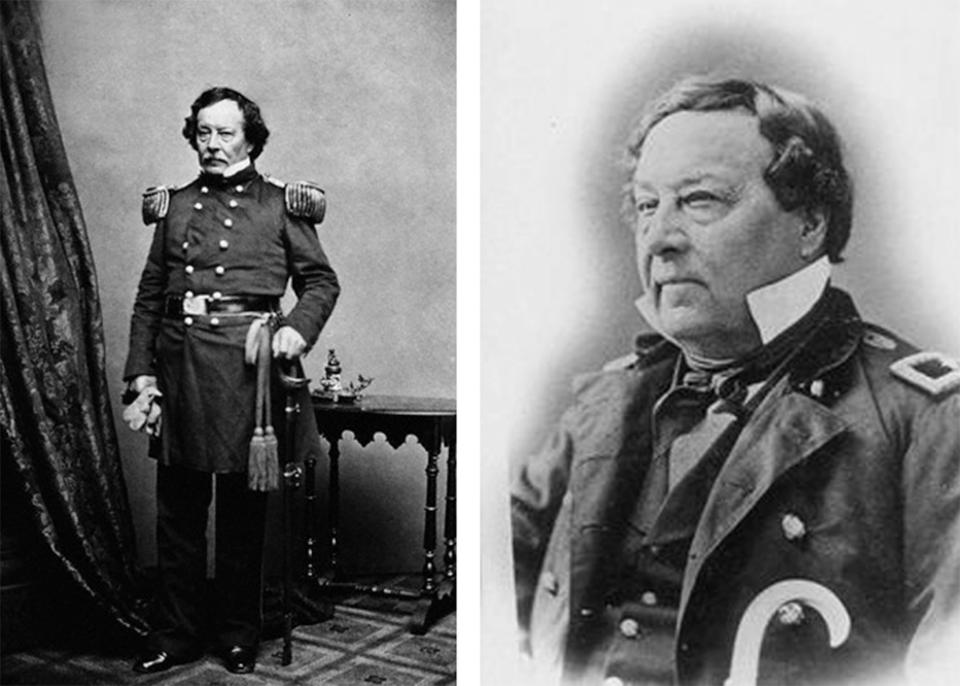

Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville was born in France in 1796 and arrived in America in 1803, along with his younger brother and mother, at the invitation of the radical author and activist Thomas Paine. Paine had lived for a time with the Bonnevilles on the outskirts of Paris after the French Revolution before returning to America the previous year. Nicholas Bonneville, Benjamin’s father, was a printer and publisher of Paine’s writings in France.

In 1815, Benjamin graduated West Point as a brevet second lieutenant. His brother Thomas served in the military and disappeared during or soon after the War of 1812. Some believe he was lost at sea. Their mother, Marguerite (Margaret) Brazier Bonneville, had taken care of Paine in his last years until he died in New York City in 1809. She died in America in 1846.

In 1821, Benjamin was serving at Fort Smith in Arkansas Territory, assigned to assist the Army with American Indian tribal relocation matters, when he obtained a leave to travel back east. There he met the aging Marquis de Lafayette, an old friend of Paine’s and prominent military figure who was instrumental in helping America obtain French financial and naval support during the American Revolutionary War.

Lafayette was on a nostalgic tour of America in 1824-1825 and Bonneville’s leave allowed him to accompany the elderly dignitary back home to France. During his tour of Washington D.C., Lafayette was the very first foreigner invited to address the U.S. Congress, which also granted him a sizeable monetary award for his service to the American cause.

Image

While in France, Bonneville visited his father, who had chosen after a brief visit to New York to return to France. Back in America, the captain continued his military service on the trans Mississippi frontier. Inspired by newspaper articles published by Oregon promoter Hall J. Kelley and expansion-minded Thomas Hart Benton, U.S. senator from Missouri, Bonneville longed to experience the far west for himself. Soon, he got the chance.

Bonneville’s Follies

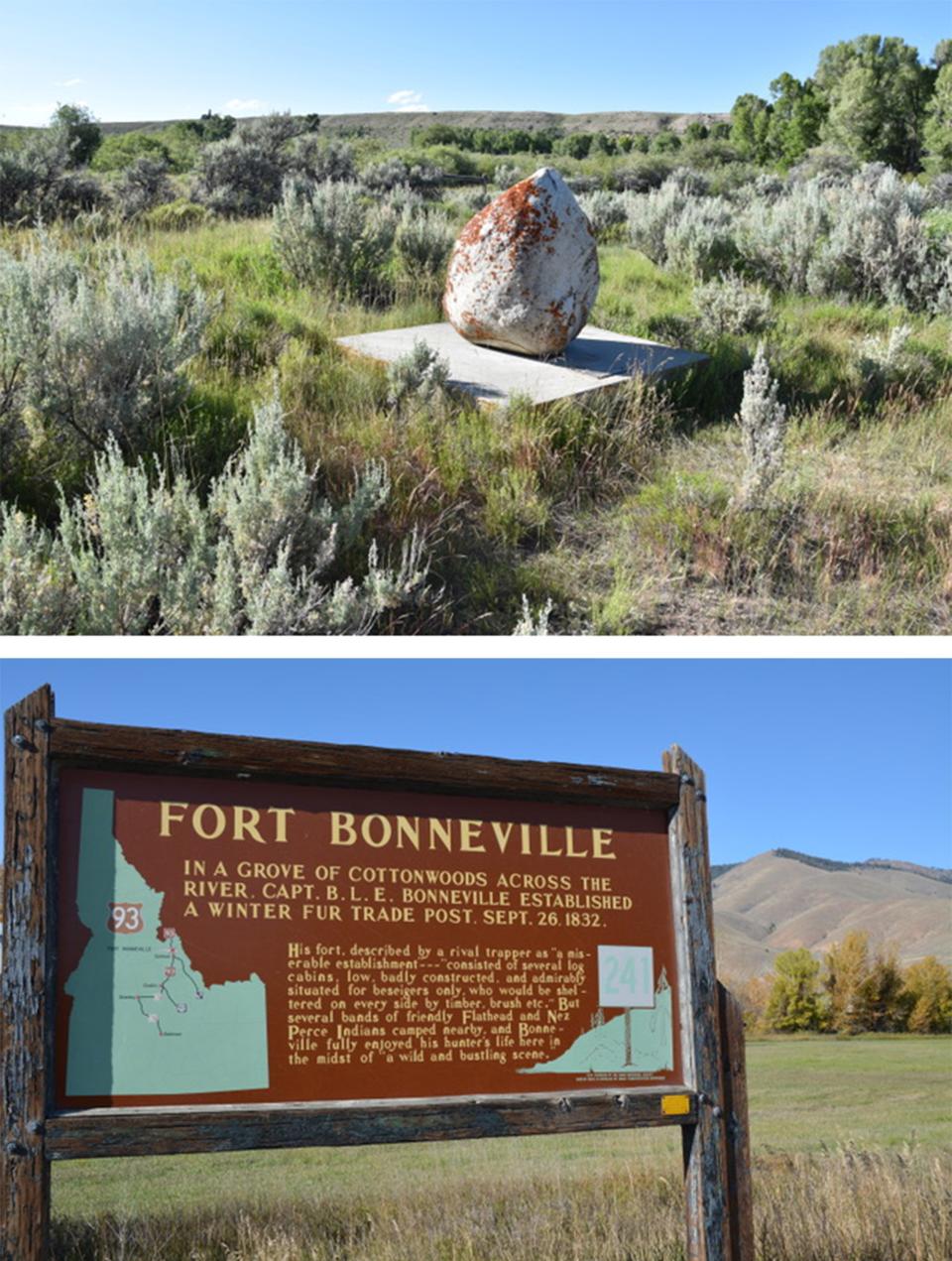

Bonnneville hoped a wagon train would speed up plains travel, but, found his progress westward was much slower than expected. Irving remarked that William Sublette’s pack train, including a large group of novices led by Nathaniel Wyeth, passed Bonneville’s train within hailing distance on their way to Pierre’s Hole west of the Tetons. Although Sublette and his men had gotten a later start, they reached the rendezvous. Bonneville did not. Instead, he crossed South Pass and built a fort near today’s Daniel, Wyoming close to the upper Green River. Intended to serve as a well-fortified winter camp, the fort was the first recorded instance of such a structure built in present Wyoming. His report to his commanding officer described the fort as a “picket work.” A small rock monument and historical marker greet visitors near Daniel today.

Warned by trappers about its poor wintertime location (to this day, Daniel records some of the nation’s lowest temperatures every winter), Bonneville spent only a few weeks building the fort and occupying the spot before before deciding to move his camp to the Salmon River in present Idaho. Mountain men derided it as “Fort Nonsense” and “Bonneville’s Folly.”

Before leaving the Green River, Bonneville also decided his wagons had gone far enough, and chose to continue instead with pack horses. After burying all of the wagons and caches of supplies at the Green River site, Bonneville and his men made their way toward the Salmon River.

Pierre’s Hole

West of the Tetons, they passed through Pierre’s Hole, where the rendezvous had recently ended—followed by a pitched battle between trappers and Blackfeet.

As rendezvous was breaking up a large band of Blackfeet-allied Gros Ventres returning with their families from a southern visit surprised some departing trappers. The trappers sent two men out to parley with the Indians—reportedly Antoine Godin and Baptiste Dorian, mixed-race Iroquois and Flathead, respectively. Godin, especially, had a score to settle against Blackfeet. The Gros Ventre chief approached the party with signs of peace. Godin shot him and took his gun and blanket. A battle erupted with casualties on both sides, many more trappers arrived from the rendezvous grounds and during the night the Gros Ventres slipped away. Bonneville and his men passed through the battle scene on their way north.

Reaching the Salmon in the fall, Bonneville established a new encampment. Today, there is a highway marker for the second Fort Bonneville where he built two cabins a few miles north and downriver from present Salmon, Idaho. Described by mountain man Warren Ferris as a temporary set of poorly built and located structures, it nevertheless provided the opportunity for Bonneville to trade with friendly Nez Perce, Flathead and other tribal members who camped nearby, or visited his makeshift post.

Soon, Bonneville noted the two tribes’ religious practices were informed, he decided, by the teachings of the “Roman Church,” teachings most likely brought to them earlier by French-speaking traders and trappers from Canada. He came to depend on these tribes to help him survive wintertime conditions over the next few years.

But just as the first Fort Bonneville had been abandoned soon after construction, this one was also. Realizing there simply were not enough resources to feed his men, horses, and all of the natives nearby, Bonneville dispersed his men, sending out trapping and hunting parties with instructions to meet back on the Salmon River later in the winter or the following summer at the next rendezvous at Fort Bonneville near Daniel. Though no longer occupied, that fort continued to serve as a gathering place for several subsequent rendezvous.

On Christmas Day 1832, Bonneville decided to cache goods and leave the Salmon River. One of his parties had not returned as promised before winter set in. Bonneville set out to find his men, which he eventually managed to do. After spending the winter and spring exploring westward as far as the Snake River and camping for a time with Flathead and Nez Perce bands at their winter encampments, Bonneville returned to the Salmon River fort to retrieve his cached supplies, and head to the rendezvous.

Image

The 1833 Green River Rendezvous

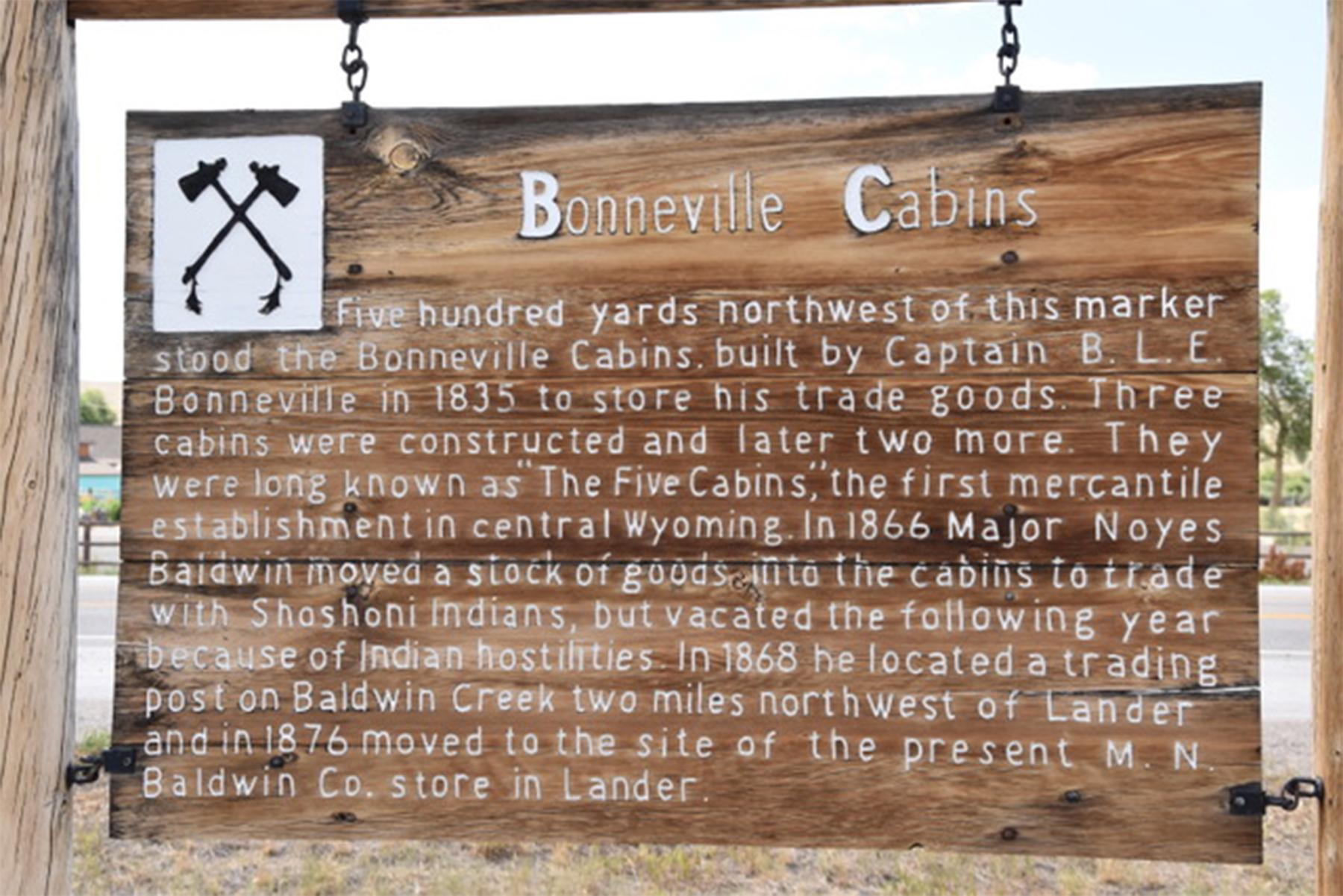

July 1833 near the Green River was another large rendezvous with lots of trading and partying by all the free trappers, fur companies and Indian people on hand. Several large tribal encampments were located nearby. In his lost report, Bonneville described “scenes of the most extreme debauchery and dissipation.”

Ferris attended the rendezvous. His description of the original Fort Bonneville was detailed and charitable:

“This establishment was doubtless intended for a permanent trading post, by its projector, who has, however, since changed his mind, and quite abandoned it…. The fort presents a square enclosure, surrounded by posts or pickets firmly set in the ground, of a foot or more in diameter, planted close to each other, and about fifteen feet in length. At two of the corners, diagonally opposite to each other, block houses of unhewn logs are so constructed and situated, as to defend the square outside of the pickets, and hinder the approach of an enemy from any quarter. The prairie in the vicinity of the fort is covered with fine grass, and the whole together seems well calculated for the security both of men and horses.”

Clearly, Ferris was more impressed with Wyoming’s Fort Bonneville than he had been with Idaho’s. His description is the source of a sketch of Fort Bonneville on the historic marker at the site today. It should be noted that some authors doubt the location, even the existence, of Fort Bonneville. But it is hard to dismiss Ferris’s description. He was a keen observer. Wherever the fort was located exactly, his description rings true.

Image

Reporting Home

Though Bonneville’s men had collected far fewer furs than other parties had, some by trading rather than trapping, they had accumulated enough to send them back to St. Louis. It was at this rendezvous that Bonneville began to worry about overextending his Amy leave, so he wrote a letter, a report, and entrusted Michel Cerré to carry it with him east with the furs. In his report, which began with information meant to comply with the army’s instructions, Bonneville informed General Alexander Macomb, now head of the U.S. Army, that distances in the west were great and that he had not yet reached lands beyond the Rocky Mountains, his main goal. He needed more time.

When the rendezvous ended, several trappers and traders, including Robert Campbell and Nathaniel Wyeth, joined together to leave for the Wind River and Bighorn River to try to float men and furs back to St. Louis. Cerré’s small party went along. Bonneville accompanied them as far as the Bighorn Canyon at the present Wyoming-Montana border where they built bullboats from reeds and skins and floated off toward the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers for the trip back home. The parties obtained other watercraft along the way to complete their journey. Cerré went on to Washington, D.C. and hand delivered Bonneville’s letter to Macomb. Soon the report went missing for almost 100 years.

As promised, Bonneville’s report included direct observations and impressions of his trip. Describing the land, rivers and mountains, minerals, flora and fauna, soil quality, weather, and the locations and size of various Indian tribes and trading companies, Bonneville provided plenty of details for the Army to digest. But along with the maps he drew (cartographers later calling them some of the best maps of western landforms and hydrology made at the time), Bonneville also included in his report other specific details obviously meant for army intelligence.

Much of the information he reported had been learned from other travelers and natives who had direct knowledge of areas he had yet to visit: “The information I have already obtained authorized me to say this much; That if our Government ever intend taking possession of Oregon the sooner it shall be done the better, and at present I deem a subalterns command”—writing confidently of a group of perhaps as few as five soldiers “equal to enforce all the views of our Government, although a subalterns command is equal to the task, yet I would recommend a full company” or perhaps as many as 60 to 100 men. Wallawallah (present Walla Walla, Washington.), he pointed out, a British post on the Columbia, was “handsomely built, but garrisoned by only 3 to 5 men, may easily be reduced by fire or want of wood which they obtained from the drift.”

As to trade matters, Bonneville remarked in his report to Macomb that “the Hudson Bay at present have every advantage over the Americans…[their articles of trade] reaching them by water in the greatest abundance and at a trifling expense, compared to the land carriage of the Americans. . . . So you see, the Americans, have to as it were to steal their own furs, making secret rendezvous and trading by stealth.”

Suffice it to say that if this report had fallen into the wrong hands, it could have escalated the long simmering international conflict between the Unites States and Great Britain over control of the Oregon country and Columbia River fur trade. At the very least, these words give a taste of what the army really wanted to learn from Bonneville’s expedition to the region.

As for Irving, if he understood Bonneville’s excursion to the far west to be a military expedition, he ignored this ulterior motive in his book. It’s more likely he never saw the captain’s report to his commanding officer.

“Cruelties” on Bonneville’s Expedition

While Bonneville was preparing at the end of the rendezvous in 1833 to leave for the Bighorn, Joseph Walker was making plans to go to California, still part of Mexico. Prior to leaving for the mountains, Bonneville had obtained a passport for Walker, another clue that organizers of the expedition had more in mind than just acquiring furs. It took almost a year, but Walker made it to Monterey Bay, met with the governor there and scouted new routes over the Sierra Nevada mountains on the way there and back. A pass traveled by Walker through the southern Sierra Nevada on his return to the 1834 rendezvous is named for him.

Walker’s men mistreated Native Americans and Mexicans. Bonneville was upset to hear these stories, as well as another involving the returning leader and sole survivor of another his parties, who returned to the rendezvous after the winter with stories of “cruelties” against Indians and “recriminations” against Whites (Irving’s descriptions) after a hostile encounter with a band of Blackfeet. For his part, Bonneville’s personal relationship with natives during his adventure was generally friendly and professional. But as captain of the expedition, Bonneville should not be held blameless for the actions of his partisans.

Exploring the Wind Rivers

After returning from the Bighorn River in 1833 and reuniting with some of his party, Bonneville proceeded north up today’s Wind River, trying to find a shorter route west through the range to his Green River fort. Though he failed to find a pass, he may have made the first ascent of Wyoming’s highest mountain, Gannett Peak. From the top, he described the source of the Green River (Colorado of the West, or Seedskedee, as he called it in his report), winding north from the western slopes of the Wind River Range before turning west and bending south. Some mountaineers have questioned whether Bonneville actually summited Gannett Peak, arguing that his descriptions suggest Wind River Peak instead.

Unable to find a more northerly passage, he and his men returned to the fort by way of the South Pass route and retrieved cached supplies at Fort Bonneville. Then, he and a small party left for the Snake and Columbia rivers.

But even though he had much help from his newly acquired Indian friends all the way through Idaho and into Oregon country, any attempts to trade for supplies with the Hudson’s Bay Company were rebuffed. While he was warmly welcomed, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s men and Indian trading partners had been instructed not to do business with Bonneville. With few supplies and winter coming on, he and his small party turned around and retraced their steps to reach a friendly wintertime encampment among natives.

During the summer of 1834, Bonneville met up with Cerré who, just back from the east coast, informed him that Macomb had been happy with his report and left the impression that Bonneville’s request for an extended leave had been granted. It had not. The last two years of Bonneville’s three-year expedition turned out to be unauthorized, though he did not know it at the time. So, once again, Bonneville immediately set off for the Columbia River, continuing his quest to reach deeper into the Oregon country. But as before, his trading efforts on the Columbia with the Hudson’s Bay Company and Indians in the region proved futile. Although he made it further west on this exploration and saw Mt. Hood near present Portland, Oregon and “Mt. Baker” (most likely Mt. Adams), he had to retrace his steps.

By the summer of 1835, Bonneville and most of his men finally headed home after the rendezvous at Fort Bonneville on the Green River. He left several men, including Walker, to continue trading and trapping in the mountains. When Bonneville reached the Wind River near today’s Hudson, Wyoming, he constructed several buildings for storing trade goods. A highway sign today marks the spot.

Bonneville Returns Home

Upon his return east, Bonneville found himself bounced out of the army for extending his leave. It took him more than a year to regain his commission and rank, an effort helped by the influence of President Andrew Jackson who ordered the Army to review his appeal. This intervention is another clue that the information Bonneville provided to the U.S. government was highly regarded.

After his adventures in the west, Bonneville served in the second Seminole War in Florida, the Mexican War and, coming out of retirement, the Civil War. He even finally made it to the lower Columbia River, where he was for several years the commanding officer of Vancouver Barracks. Following the death of his first wife and a daughter in 1862, Bonneville married a woman many years his junior in 1871. He died in 1878 at Fort Smith, Arkansas where he had built a home. At the time of his death, he was the U.S. Army’s oldest retired officer, a brigadier general. According to the army’s obituary, he was living a “quiet, happy life.”

Resources

Sources

- Abel-Henderson, Anne H. “General B.L.E. Bonneville.” Washington Historical Quarterly 18, no. 3 (1927), 207-230, accessed Jan. 10, 2024 at https://journals.lib.washington.edu/index.php/WHQ/issue/view/511.

- Bagley, Will. South Pass, Gateway to a Continent. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

- Barry, J. Neilson. “Captain Bonneville.” Annals of Wyoming 8, no. 4 (1932), 608-633, accessed Jan. 10, 2024 at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom8141932wyom/page/608/mode/2up.

- Bernier, Olivier. Lafayette, Hero of Two Worlds. New York: E.F. Dutton, 1983. 292-298.

- Chittenden, Hiram M. The American Fur Trade of the Far West. New York: Francis P. Harper, 1918. E-book, Astoria Printing, 2018. Ch. 24.

- Conner, Jett B. Captain Benjamin Bonneville’s Wyoming Expedition, The Lost 1833 Report. Charleston: The History Press, 2021.

- Eddins, O. Ned. “Was Fort Bonneville Really Nonsense?” Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal 5 (2011), 21-33.

- Ferris, Warren Angus. Life in the Rocky Mountains. The American Mountain Men Organization, accessed Jan. 10, 2024 at http://www.mtmen.org/mtman/html/ferris/ferris5.html

- Hardee, Jim. Pierre’s Hole! The Fur Trade History of the Teton Valley, Idaho. Pinedale, WY: Sublette County Historical Society, 2010.

- Schaubs, Michael (Malachite). “Battle of Pierre’s Hole” in Mountain Men and Life in the Rocky Mountain West, a website accessed Jan. 10, 2024 at http://www.mman.us/PierresHoleBattle.htm. The article includes links to five first-person accounts of the fight.

- Irving, Washington. Three Western Narratives: A Tale of the Prairies, Astoria, the Adventures of Captain Bonneville. New York: Library of America, 2004. 617-956.

- Lovell, Edith Haroldsen. Benjamin Bonneville, Soldier of the American Frontier. Bountiful, UT: Horizon Publishers, 1992.

- Sunder, John E. Bill Sublette, Mountain Man. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959.

- Wolf, James R. “Bonneville’s Foray: Exploring the Wind Rivers in 1833.” Annals of Wyoming 63, no. 3 (1991). 93-104.

Illustrations

- The two photos of Capt. Bonneville are from the National Park Service and Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- Bonneville’s 1837 “Map of the territory west of the Rocky Mountains” is from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- Laurent Dabos’s portrait of Thomas Paine, ca. 1792, is from the National Portrait Gallery. Used with thanks.

- Samuel Morse’s 1826 portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of South Pass is by longtime historic trails advocate Barbara Dobos. Used with thanks.

- Alfred Jacob Miller’s painting of a fur-trade rendezvous is from the Walters Art Museum. Used with thanks. Miller was at the 1837 rendezvous.

- The rest of the photos are by the author. Used with permission and thanks.