- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Sherman Coolidge: Arapaho Priest In a Changing ...

Sherman Coolidge: Arapaho Priest in a Changing World

When the Episcopal priest and Native rights activist Sherman Coolidge died in 1932, the Wyoming State Tribune’s obituary noted that the “solution of the Indian problem” had been “one of the greatest desires” of his life.

“Coolidge himself,” the Tribune continued, “could be taken as an example of his contentions of the complete adaptability of the Aboriginal Indian to the customs, civilization and culture of the white man.”

Born to Northern Arapaho parents and then adopted by a U.S. army officer and his wife around age 9, Coolidge was the literal embodiment of his own message. He believed that assimilation to Euro-American norms—inspired by conversion to Christianity—held the key to erasing not only conflict between Whites and American Indians, but conflict among Indians themselves. Why Coolidge felt so strongly about the need for peace and intertribal harmony is a story rooted in the harrowing violence of his childhood.

Early years and conflicts with the Shoshone

Sherman Coolidge was born near the upper waters of the Bighorn River, present-day Wyoming, sometime in the early 1860s. His father, Banasda (Big Heart), a warrior, and mother Ba-ahnoce (Turtle Woman), named him Doa-che-wa-a, or He-Runs-on-Top, after an ancestor who had led his band over a frozen lake to elude an enemy tribe. The family grew over the subsequent years, with addition of a younger brother. At that time, traditional Arapaho lifeways had not yet succumbed to the pressures of American expansionism, and the family’s band continued to migrate over their established territory, sustained by hunting and gathering. The Arapaho’s primary antagonists were the Eastern Shoshone, who, under Chief Washakie, competed for the region’s dwindling resources.

When He-Runs-on-Top was just old enough to remember, he had his first encounter with the enemy. In the dead of night, Shoshone warriors raided his band’s camp, slaughtering indiscriminately until the Arapaho resisted. A series of similar tragedies followed. He-Runs-on-Top lost his grandmother, aunt and uncle in an attack by American soldiers who had mistaken them for Lakota.

These painful losses were but a prelude to the death of He-Runs-on-Top’s father. In early spring 1867, the family was camped by a stream for the night when they were awakened by war cries. Everyone escaped into the darkness, but Banasda remained to fight off as many attackers as he could. His body was recovered a day later, shot through the chest. Ba-ahnoce, now in deep mourning, was left to care for her two boys.

The period following Banasda’s death was one of increasing violence on the Great Plains. The Bozeman Trail, a newly established offshoot of the Oregon Trail leading through Wyoming’s Powder River Basin to Montana gold fields, became a flashpoint. Raids on wagon trains and bloody victories over the U.S. military by the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho forced Washington to seek peace in early 1868.

The resulting Treaty of Fort Laramie created the Great Sioux Reservation in Dakota Territory and secured for the Sioux the hunting grounds of the Powder River Basin, supposedly in perpetuity. It did not, however, create a reservation for the less populous Northern Arapaho, who reluctantly agreed—in time—to settle among the Lakota or in present-day Oklahoma among their Southern Arapaho kinfolk. The Arapaho chiefs, determined to agitate for a reserve of their own, eventually approached Washington with an unexpected idea.

Wishing to live in their traditional homeland, they requested permission to settle alongside the Eastern Shoshone on their reservation on Wind River, established in the 1860s. Commissioners assented, brokering an agreement with Washakie to allow the Arapaho a temporary home. Many Shoshone people today, however, maintain that Washakie made no such agreement at that time, and the Arapaho presence was hardly welcome. Before their arrival, rumors flew among White settlers that the Arapaho had killed three miners. When on April 8, 1870, a band of Northern Arapaho made their way to receive rations at the reservation’s administrative center, Camp Brown (now Lander), White mobs, joined by some Shoshone, attacked.

The assault was brutal. An elderly man, begging for his life, was bludgeoned to death before He-Runs-on-Top’s eyes, and he himself was almost executed by several Shoshone men who debated whether he was old enough to pose any danger. He was then 9 years old. The boy and his family were ultimately surrendered to U.S. troops at Camp Brown, where Ba-ahnoce, exhausted, gave up her sons to the care of two army officers and the camp surgeon, Dr. Shapleigh.

Adopted by Charles and Sofie Coolidge

He-Runs-on-Top, deeply traumatized, and in the hands of strangers, was heartbroken to see his mother depart. Shapleigh, the boy’s new guardian, renamed him William Tecumseh Sherman after the Union Army general. Then, in May 1870, the Utah-based 7th Infantry passed through Camp Brown. With them was Lieutenant Charles Austin Coolidge, a young, mustached man of Pilgrim ancestry who would play a formative role in He-Runs-on-Top’s life.

Charles and his wife, Sofie, adopted the boy and took him east to New York City. The Coolidges, both devoutly religious and fervently patriotic, instilled these qualities in their new son, along with the rigid Euro-American ethnocentrism typical of the 19th century. Sherman, as they began to call him, was baptized at Grace Episcopal Church in lower Manhattan, and placed in a segregated school for African American children. The Coolidges spent three years in the East, until Charles was called back to Montana Territory in 1873.

In their absence, violence in the West had continued. The Northern Arapaho had returned to the Powder River Basin to hunt the dwindling bison, intermittently raiding the Shoshone and White settlers at the Shoshone Reservation on Wind River. The Shoshone retaliated in kind, cooperating with U.S. troops to attack the Arapaho and steal their horses. The Coolidge family, meanwhile, lived at Fort Shaw on the Sun River in northern Montana Territory, where Sherman attended the post school.

This life was disrupted by an explosion of tensions between U.S. forces and the Lakota in the summer of 1876, when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer perished at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Charles Coolidge’s unit arrived at the scene two days later and began burying the dead. Sherman, by now a teenager, refused to join them.

Charles, having seen Sherman grow into a bright and physically imposing young man, thought a military career would best suit his talents. Throughout the first half of 1877, Sherman accompanied his adoptive father on military expeditions against the Lakota. Witnessing these scattered conflicts in the final months of what became known collectively as the Great Sioux War convinced Sherman that a life in the military was anathema.

He began to lobby Sofie, explaining his desire to study for the ministry. She wrote the Episcopal bishop of Minnesota, Henry Benjamin Whipple, for advice. Whipple, a noted advocate of what he saw as humane Indian assimilation, suggested Shattuck Military School, an Episcopalian-run institution in Faribault, Minn.

Studying for the ministry

In mid-1877, Sherman set off by steamboat and rail. In Minnesota, he lost the train ticket for the last leg of his journey, but managed to convince an amateur boat builder to ferry him down the Mississippi to his destination. When he finally reached Faribault, he presented himself to Shattuck’s rector filthy and in rags. Sherman spent three years at Shattuck, and upon graduation in 1880 approached Whipple about studying for the ministry at Seabury Divinity School, also in Faribault.

“My people have never heard of the Savior,” he purportedly stated, “If possible, I would like to become a minister and go back to tell my kinsmen of the love of Jesus Christ.” Sherman graduated from Seabury in 1884. Now a deacon, he prepared for the long journey west.

Sherman arrived at Wind River on Oct. 2, 1884, ready to assist the resident Episcopal missionary, John Roberts. Originally from North Wales, Roberts had established a mission among the Shoshone in 1873. In the seven years Sherman had been away, the Northern Arapaho had failed to secure their own homeland. They had ended up alongside the Eastern Shoshone at Wind River with little prospect of relocation. Two once-warring nations were forced to make peace while trying to preserve their cultures under the restrictive control of the government’s Indian Bureau.

Reunion with relatives

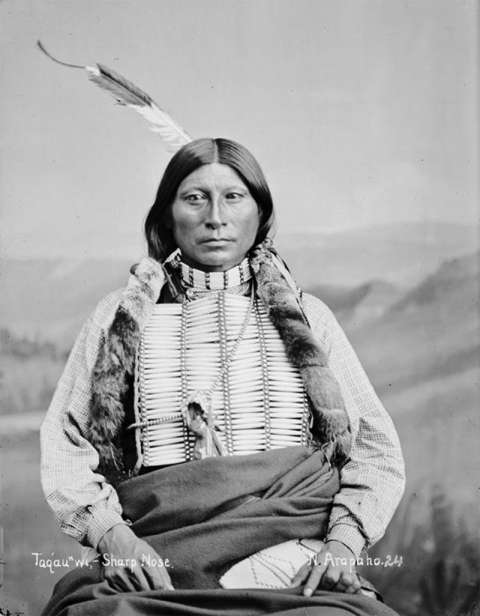

Before Sherman Coolidge reached Wind River by stagecoach on a fall evening in 1884, word had already spread among the community that the “Arapaho Whiteman,” as he was called by his tribespeople, was on his way. His impending arrival was an extraordinary event for one Arapaho woman: He-Runs-on-Top’s mother, Ba-ahnoce, who had survived 15 years of raids, war and near starvation. To Coolidge’s utter shock, Ba-ahnoce and a succession of relatives greeted him in tears, each resting their head on his shoulder. Among them was his uncle, Sharp Nose, one of the primary chiefs on the reservation.

A quarter century on the reservation

This auspicious beginning, however, did not lead to future success. Coolidge would spend the next 26 years in Wyoming (with the exception a period of study at Hobart College, in Geneva, N. Y.), attempting and largely failing to convert his former tribe to Christianity. After being ordained into the priesthood in 1885 by the bishop of Colorado, John Spalding, Coolidge took on multiple roles on Wind River, as schoolteacher, priest, government clerk and unelected mediator.

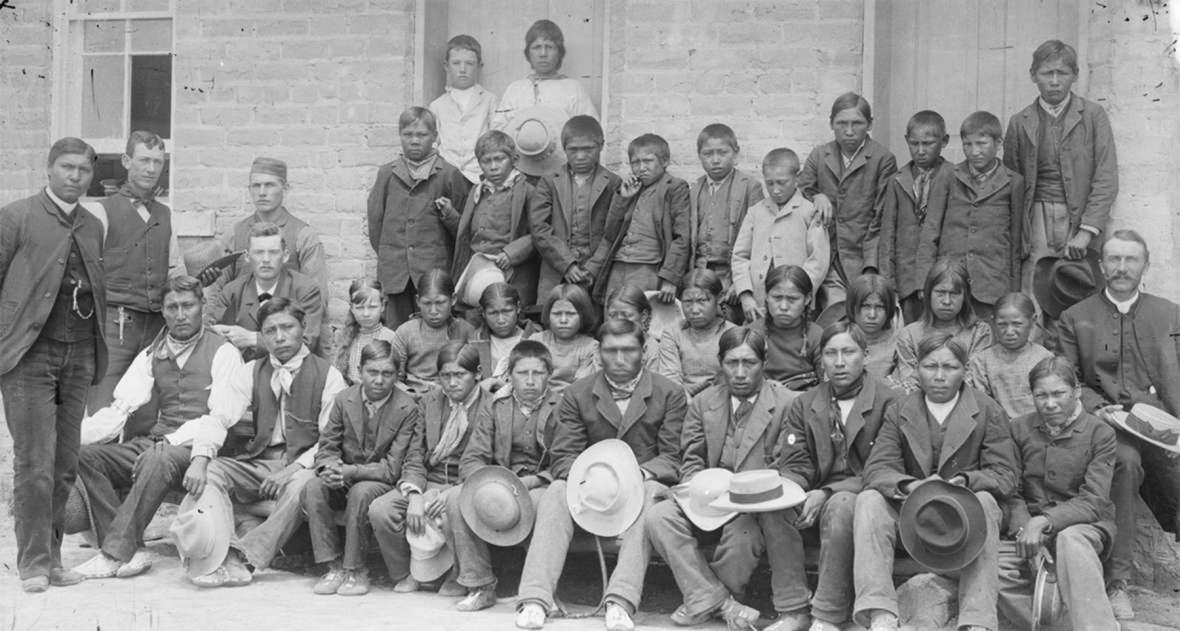

Circumstances were difficult for his potential congregants. Government policy treated the Arapaho as dependent wards, while seeking to eliminate their traditional ways and beliefs. Those who did not comply were punished through reduced rations and even imprisonment. Assimilation in practical terms meant farming, though Wind River did not boast much suitable soil. Few Arapaho showed an interest in the plow. Efforts to enforce new lifeways were coupled with attempts to “civilize” the tribe’s children through Christian education. With the Indian Bureau’s blessing, two church schools operated on the reservation—the Episcopal school, and St. Stephens, run by the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions. Coolidge established a home strategically located among the main Arapaho camps, from which he tried to gain converts.

Supporting government policy

Since Coolidge was a missionary of Native descent, one might have expected him to side with the Northern Arapaho against government policies they clearly opposed. Not so. Instead, Coolidge consistently allied himself with the government’s agents in imposing Washington’s will. First, in the 1890s, he supported the cession of the “Smoking Waters,” the hot springs at present-day Thermopolis, coveted by the local White population.

Then, in 1901 and 1902, he became embroiled in a conspiracy with Indian Bureau agent Herman Nickerson to pit the younger, more “progressive” members of the tribe against their elders in an attempt to implement the Dawes Act. This plan, wildly unpopular among the Arapaho, sought to divide reservation lands among individuals, encourage farming and end collective, tribal ownership.

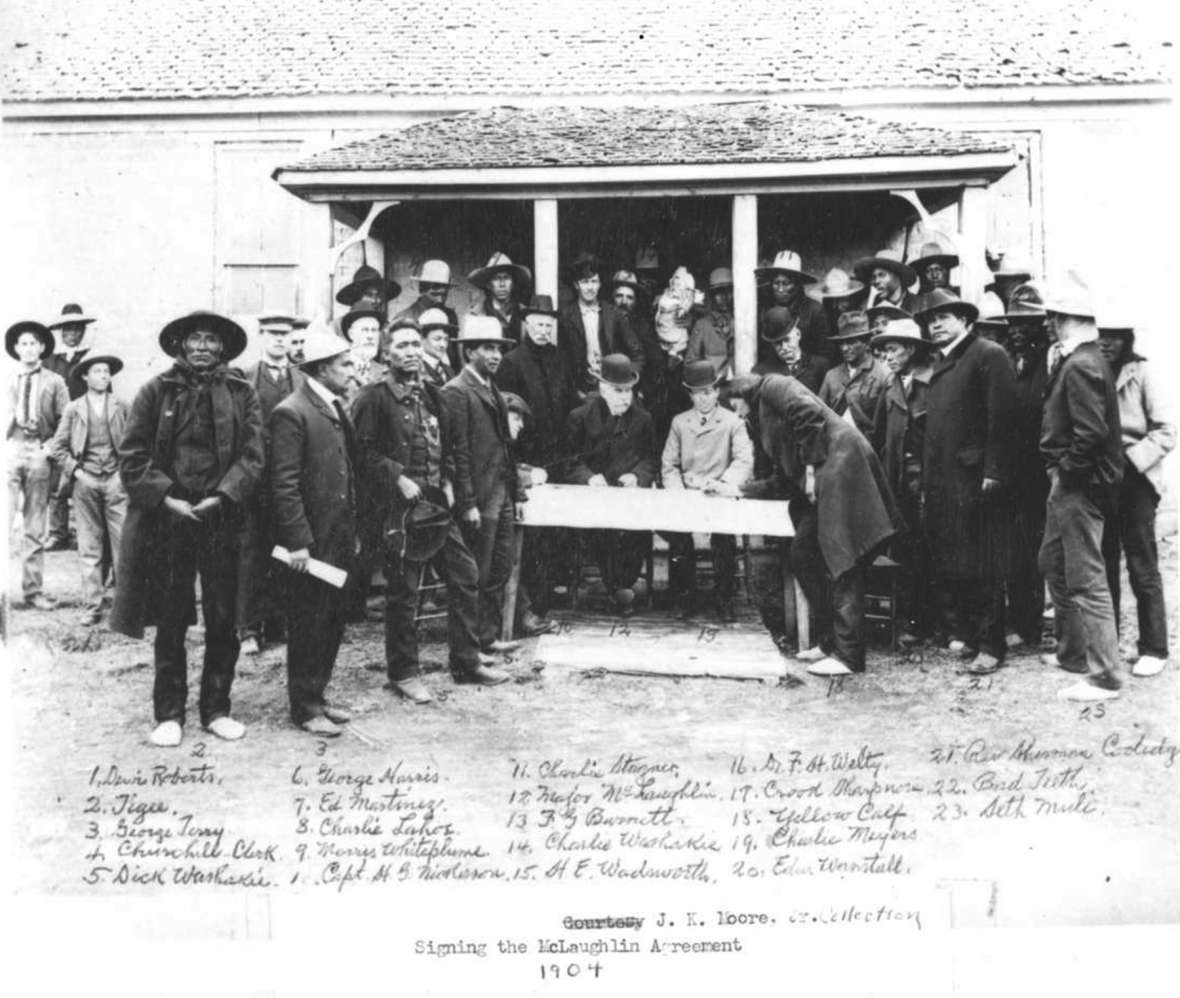

The only reason Coolidge and Nickerson were foiled was because the Catholics at St. Stephens intervened in Washington to have Nickerson dismissed. The debacle was a serious blow to Coolidge’s reputation, laying bare his lack of sympathy with most Arapaho. Coolidge sided with the U.S. government again in 1904, arguing for more land cessions. Deaf to the concerns of those at Wind River, he continued to argue that with “aggressive and progressive” work among the “clannish” Arapaho and Shoshone, the “bitter hereditary foes could be united in the brotherhood of Christ,” and “live side by side in peace and harmony.”

Marriage to a white heiress

Fortunately, outside of Wyoming, Coolidge proved a more effective advocate for Native peoples. His lectures to church groups in the East never failed to elicit donations, and his personality, eloquence and humor won over many Whites dubious about the inherent intelligence of Indians. Still, Coolidge’s efforts did little to ameliorate the larger structural problems that came with forced assimilation, such as poverty, malnutrition and disease.

In the midst of the bitter controversies swirling around Indian Bureau policy on Wind River, Coolidge met and fell in love with a young, idealistic woman named Grace Darling Wetherbee, who had taken a keen interest in Indian missionary work. Born in 1873, she had come to Wyoming from Manhattan in New York City, where her father owned and operated the tallest hotel in the world. Sherman and Grace’s courtship lasted only a few months. Their marriage in October 1902 caused a national sensation, garnering headlines such as “Society Girl’s Heart and Hand Captured by an Indian.”

The Coolidges remained on Wind River, and if reports are to be believed, Sherman traded in his teepee for a modern home at his new bride’s behest. Together, the couple adopted two girls, an Arapaho and a Shoshone, who later studied at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa. The Coolidges also had three daughters and two sons of their own. Tragically, only two of the children, daughters, survived infanthood. Sherman and Grace worked actively to immerse themselves in reservation life. Some respected them, even if their “progressive” ideas and proselytizing for Christianity alienated others.

A near-deadly incident

Proof of the latter came in February 1907, when an almost deadly incident revealed the bitterness many Arapaho felt toward Indian Bureau policy and the Episcopal missionary presence. One evening John Roberts was coming home from a trip to Lander. Near the border of the reservation, a group of Arapaho, frustrated by the Indian Bureau’s ban on their annual Sun Dance religious ritual, began pursuit, clearly intending to murder him. Roberts retreated to Lander, and telephoned the commanding officer at Fort Washakie, the former Camp Brown. Troops escorted him home, and Coolidge, away in Salt Lake City, returned immediately to exercise any calming influence he could.

Leaving Wyoming

Despite the attempt on Roberts’s life and his own growing discouragement with “progress” on the reservation, Coolidge stayed on another three years.

In 1910, the Episcopal hierarchy transferred him to Oklahoma. There, Coolidge took charge of the Episcopal mission at Whirlwind, on the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho reservation established in the 1860s. According to one Episcopal journal, his assignment was to convert 200 “blanket Indians who live in teepees and still cling to many of the old-time customs.”

Coolidge and his family detested life in Oklahoma. Sherman, likewise dissatisfied with his work, requested a transfer. In the spring of 1912, the Coolidges relocated to Faribault, Minn., where Sherman ministered to White and Dakota congregations at a local Episcopal church.

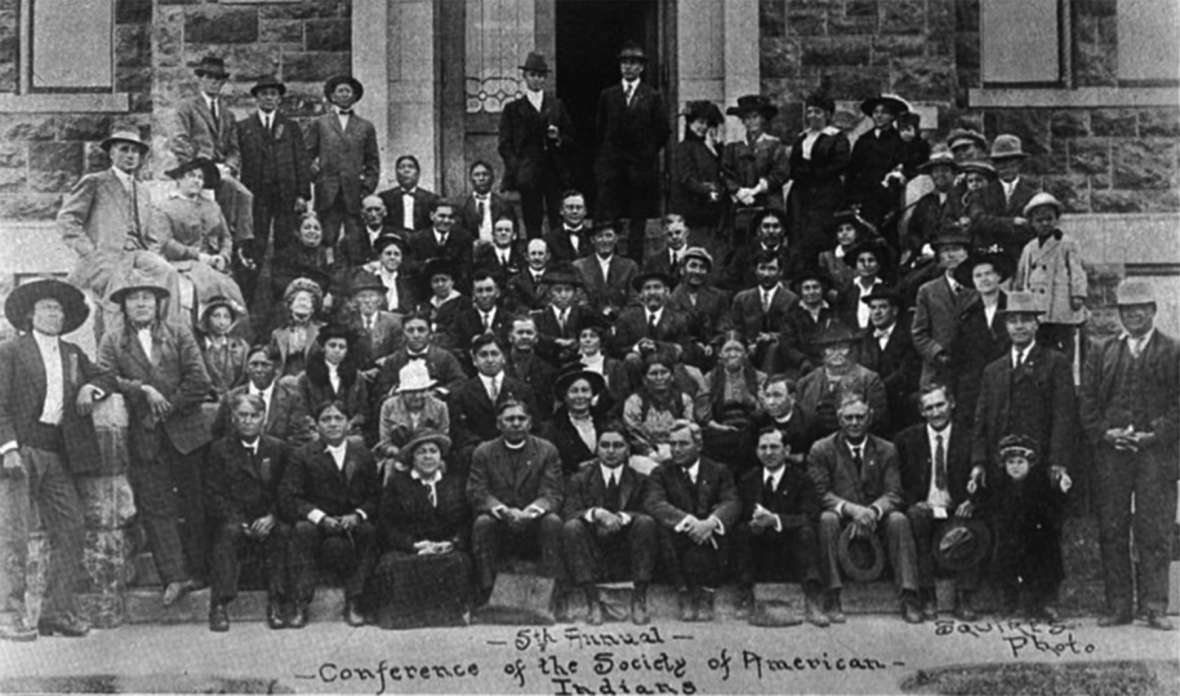

The Society of American Indians

These years turned out to be crucial in Coolidge’s mission to raise awareness of Indian issues among a wider audience. In October 1911, he traveled to Columbus, Ohio, to take part in a major breakthrough in American Indian activism. Together with a group of prominent Natives, such as the Yavapai physician Dr. Carlos Montezuma and the Santee Dakota writer and physician Charles Eastman, Coolidge founded the Society of American Indians (SAI). Those present formed a Temporary Executive Committee and made plans to open an office in Washington, D.C.

The SAI’s original conference call highlighted the ideal of Indian “self-help” through the “attainment of a race consciousness and a race leadership.” The organization, which only granted full membership to people of indigenous descent, brought together Natives from disparate tribes across the United States irrespective of cultural differences. While assimilation to mainstream Euro-American society was encouraged, the SAI did not support an erasure of Native identities. Coolidge was elected the first president of the organization, and held the post for five years. His time in the Society softened his views on assimilation considerably, and he began to view Indian cultures as valuable. In one speech he even noted that “the old religion of our people...was not so very bad after all.”

The history of the Society of American Indians is intricate and difficult to encapsulate through the experience of just one of its figures. Nonetheless, the character of Coolidge’s presidency can be briefly presented. As a leader, he became a moderating force within the society, always pleading for members to show discipline and curtail infighting, and always able to diffuse a heated debate with humor. The controversial question of Indian Bureau abolition was one often raised by certain members.

Conflict in the Society

In one infamous incident, Carlos Montezuma presented a forceful speech in favor of eliminating Bureau wardship in order to liberate reservation populations. His sentiments were seconded by the Ojibwe Catholic priest and missionary, Philip Gordon, who tactlessly declared that any Indian working for the Indian Bureau could not be loyal to the Society. The remarks caused an uproar among the Bureau employees present.

Coolidge defended them, terminating the discussion by asking “Is it right for us to act this way?”

Montezuma jumped out of his chair and shouted, “I am an Apache and you are an Arapaho. I can lick you. My tribe has licked your tribe before.”

Coolidge, who stood at least a head taller than his rival, replied calmly, “I am from Missouri.” The remark made no sense, but it did break the tension. The incident, in fact, was a friendly rivalry between friends—but the disagreement over Bureau abolition had lasting consequences. Coolidge’s more moderate views eventually became irrelevant to the Society as the membership cultivated a crippling factionalism over matters such as the Indian Bureau and ceremonial use of peyote. Nonetheless, he stayed active till the very end. In 1920, Coolidge was one of the few to attend the annual meeting. The Society of American Indians limped on for three more years, effectively expiring in 1923.

Moving to Colorado and advocating for Natives

In 1919, the Coolidges relocated to Colorado, where Sherman became canon at the Cathedral of St. John in the Wilderness in Denver. Throughout the following decade, he continued to be active in Native rights causes. The culmination of his career came in 1923, when he served on the Committee of One Hundred, chosen by Secretary of Interior Herbert W. Work to investigate conditions on reservations and report on the challenges facing indigenous peoples in the United States. Sherman Coolidge met with President Coolidge in December of that year.

Back in Denver, the Arapaho priest established himself as a beloved figure. His unexpected death at approximately age 72 on Jan. 24, 1932, during a stay in Los Angeles, caused great mourning. He was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Colorado Springs. Grace survived him by five years, dying in 1937. One of her last acts was a $7,000 donation to the mission on Wind River. She also published a collection of stories about her time in Wyoming, Teepee Neighbors (1917).

Wyoming Citizen of the Century nomination

In the 1990s, Canon Coolidge was nominated for Wyoming citizen of the century. Though many scholars today would rightly look askance at his assimilationist projects, Coolidge’s ideal of intertribal peace and solidarity through the panacea of Christianity remains compelling in the context of his childhood of extreme violence and unfathomable trauma.

Still, one cannot help but feel that Sherman Coolidge would have preferred this biographical sketch to end on a humorous note. So why not? Once while Sherman was visiting his adoptive parents, Charles Coolidge went on and on, boasting of how his venerated ancestors had come over centuries ago on the Mayflower. Sherman retorted: “Oh, that’s nothing…mine were on the reception committee.”

Editor’s note: Special thanks to Wyoming Humanities, which supported development of this article.

Resources

Archives

- Coolidge, Sherman, Biographical File, Grace Hebard Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- Coolidge, Sherman, File, Cathedral of St. John in the Wilderness Archives, Denver, Co.

- Coolidge, Sherman, File, Warren Hunting Smith Library Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, NY.

- Coolidge-Heinicke Collection, Pioneers Museum, Colorado Springs, Colo.

Primary Sources

- “An Indian Boy, Slated for Death at Fort Brown, Where this City Now Stands, Now Minister of Gospel.” Oct. 31, 1921. Sherman Coolidge Biographical File, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- “Announcements,” Spirit of Missions 77.1 (January 1912): 165.

- “Canon Coolidge is Claimed by Death.” Wyoming State Tribune, Jan. 25, 1932.

- “Conference Evening at Haskell Indian School: An Extract from the Haskell Indian Leader.” Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians 3.4 (October–December 1915): 300.

- “Connecticut Letter.” Church Standard 74 (November 1897): 91.

- Coolidge, Grace. Teepee Neighbors. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984. Reprint.

- Coolidge, Sherman. “Report from Sherman Coolidge.” Spirit of Missions 64 (January 1899): 14.

- _______________. “The Indian of To-Day.” The Colorado Magazine 1.2 (May 1893): 87–94.

- _______________. “Report from Sherman Coolidge.” Spirit of Missions 51 (1886): 57.

- _______________. “Sherman Coolidge Autobiographical Notes.” Coolidge-Heinicke Collection.

- _______________. “A Sketch from Real Life.” Coolidge-Heinicke Collection.

- Coolidge, Sherman and Grace Coolidge. “The Death of Brave Heart (Great Heart).” Coolidge-Heinicke Collection.

- Coolidge, Sherman to Grace Coolidge, Feb. 28, 1911. Coolidge-Heinicke Collection.

- Goodnough, Myfanway Thomas. “Sherman Coolidge.” Rock Springs Miner, Feb. 22, 1935.

- Gustin, Marion. “Arapaho is Distinguished Churchman.” Ca. 1932. Sherman Coolidge File, Warren Hunting Smith Library Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, N.Y.

- “Indian Troubles in Boise.” Churchman 95 (February 1907): 248.

- “Newark.” Church Standard 74 (December 1897): 169.

- “News and Notes.” Indian’s Friend 10.7 (March 1898): 5.

- “Open Debate on the Loyalty of Indian Employees in the Indian Service.” American Indian Magazine 3.4 (Fall 1916): 252–56.

- “Our Letter Box.” Spirit of Missions 76 (March 1911): 242.

- Report of the Executive Council on the Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Society of American Indians.Washington, D. C., 1912, 92.

- “Society Girl’s Heart and Hand Captured by an Indian.” Denver Post, Oct. 24, 1902.

- Spalding, John. “Second Annual Report of the Jurisdiction of Wyoming.” Spirit of Missions 50 (1885): 617–18.

- Van Orsdale, J. T. “Rev. Sherman Coolidge, D. D.” Colorado Magazine 1.2 (May 1893): 85–86.

- Whipple, Henry Benjamin. Lights and Shadows of a Long Episcopate: Being Reminiscences and Recollections. New York: Macmillan, 1899, 163.

- ____________________. “Bishop Whipple’s Address to the Twenty-Eighth Annual Council of the Diocese of Minnesota.” Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual Convention of the Diocese of Minnesota. Minneapolis, Minn.: Johnson, Smith & Harrison Printers, 1885, 32.

- Woodward, Robert I. “Notes About the Reverend Sherman Coolidge.” Aug. 4, 1996. Sherman Coolidge File, Cathedral of St. John in the Wilderness Archives, Denver, Colo.

Secondary Sources

- Brown, Dee Alexander. The Fetterman Massacre. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1984, 13–14.

- Carlson, Paul H. The Plains Indians. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1998, 157– 62.

- “The Coolidge Family,” Finding Aid, Coolidge-Heinicke Collection.

- Ellis, Amanda M. Pioneers. Colorado Springs, Colo.: Dentan Printing Company, 1955, 13–14.

- Fowler, Loretta. Arapaho Politics, 1851–1978: Symbols in Crises of Authority. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1982, 47–51, 59–65, 105–107, 324 n59.

- ____________. The Arapaho. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989, 59–63.

- Hertzberg, Hazel W. The Search for an American Indian Identity: Modern Pan-Indian Movements. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1971, 36–38, 146–49, 193–94, 202.

- Lazarus, Edward. Black Hills/White Justice: The Sioux Nation versus the United States, 1775 to the Present. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1999, 39.

- Lewandowski, Tadeusz. Ojibwe, Activist, Priest: The Life of Father Philip Gordon, Tibishkogijik. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2019, 63–64.

- Markley, Elinor R. and Beatrice Crofts. Walk Softly, This is God’s Country: Sixty-six Years on the Wind River Indian Reservation, Compiled from the Letters and Journals of the Rev. John Roberts, 1883–1949. Lander, Wyo.: Mortimore Publishers, 1997, 100, 141–47.

- Maroukis, Thomas Constantine. “The Peyote Controversy and the Demise of the Society of American Indians.” American Indian Quarterly 37.3 (Summer 2013): 159–80.

- Nicholson, Christopher L. “To Advance a Race: A Historical Analysis of the Personal Belief, Industrial Philanthropy and Black Liberal Arts Higher Education in Fayette McKenzie’s Presidency at Fisk University, 1915–1925.” Ph.D. diss., Loyola University, Chicago, 2011, 32–37.

- Olson, James C. Red Cloud and the Sioux Problem. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 27–45.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel. The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. New York: Penguin, 2011, 255–66.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, People. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, 329.

- Speroff, Leon. Carlos Montezuma, MD, A Yavapai American Hero: The Life and Times of an American Indian, 1866–1923. Portland, Ore.: Arnica Publishing, 2005, 333–34.

- Stamm, Henry E. People of the Wind River: The Eastern Shoshones, 1825–1900. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999, 56–57, 127–29, 222.

For further research

- “Carlos Montezuma: Changing is Not Vanishing.” 28-minute documentary on the life of Yavapai activist, physician and journalist Carlos Montezuma, one of the founders of the Society of American Indians, accessed June 17, 2020 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1arhXZjQIY&t=346s.

Illustrations

- The photo of Cherokee activist Ruth Muskrat Bronson presenting a book to President Calvin Coolidge while Sherman Coolidge looks on is from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

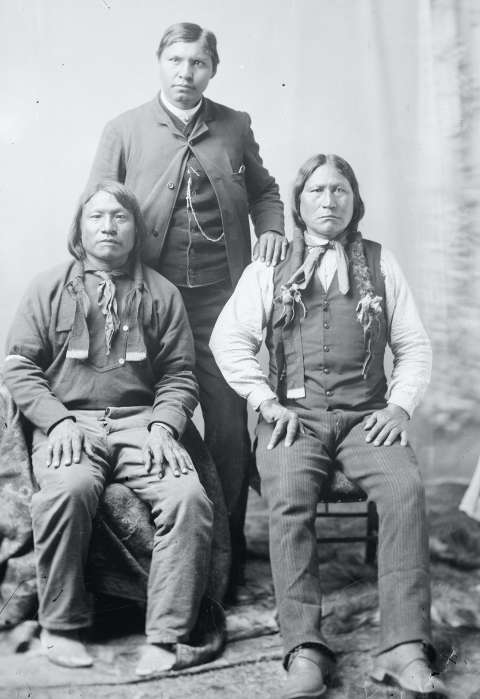

- The photo of Coolidge with Black Coal and Painted Wind is from the American Heritage Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Coolidge at the 1905 signing ceremony for the cession of more tribal land to the U.S. government is from the American Heritage Center via the website of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum, where the image is #388 in the "Wind River Treaty Councils and Signings" section of the website's Wind River Photo Gallery. Used with permission and thanks.

- The portraits of Sherman Coolidge, Grace Wetherbee Coolidge, Carlos Montezuma and Charles Eastman and the 1915 photo of the Society of American Indians are from Wikipedia articles on Coolidge and on the Society of American Indians. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Sharp Nose is from firstpeople.us. Used with thanks.