- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Pictures On Rock: What Pictographs and Petrogly...

Pictures on Rock: What Pictographs and Petroglyphs Say about the People Who Made Them

The earliest people appear to have come to Wyoming from Asia, about 11,000 years ago. For thousands of years, they roamed the plains hunting big game on foot. Some of the animals were enormous—mammoths and giant bison, for example. Such others as camels and horses were about the size they are now. Probably the people worked in small groups, ambushing prey at springs or streams, preferring the younger and smaller mammoths and butchering two or three at a time. Many of the big mammals went extinct eleven or ten thousand years ago. About 7,000 years ago, a drought began that lasted 2,000 years. Bison and people seem to have disappeared from the plains altogether. In Wyoming, the people moved up into the mountains where it was cooler, and where there was water.

By 4,500 years ago, people had returned to the plains. Sometimes they stayed in caves and rock shelters. They gathered plants and ground the seeds, they fished, and they hunted and ate small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. By that time the giant bison had been replaced by the modern Bison bison — what we call buffalo.

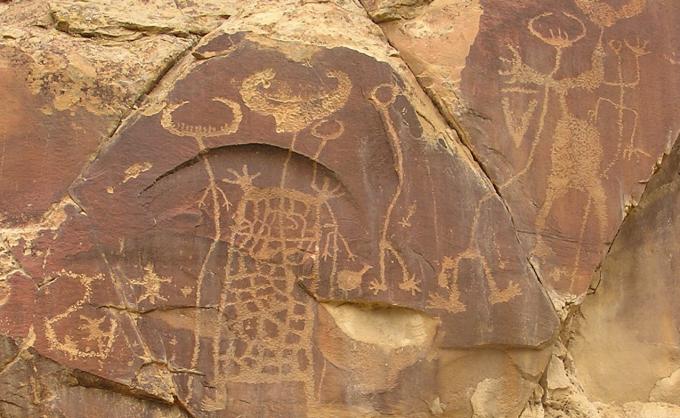

Around 500 A.D., people began using bows and arrows. In Wyoming they left rings of stones where they had pitched their tipis, and much larger stone circles oriented to the sun and stars. And they left pictures and carvings on rocks. When we look at those carvings now, we can’t help but wonder about the ancient people who made them. Who were they? What was important to them? How did they make these pictures? And why?

Archaeologists now think there’s a good chance the people were direct ancestors of Shoshone people who live in Wyoming now, many of them on the Wind River Indian Reservation. And in recent years, the mostly white archaeologists have realized it makes sense to ask Shoshone people for help understanding the pictures and carvings their ancestors left on the rocks. Take, for example, the water ghost woman, whose image is on a rock face in Hot Springs County, near Thermopolis.

She may be Pa waip, a spirit woman of Shoshone stories. She’s definitely female, as can be seen from her breasts — a detail omitted from most rock images. Pa waip lives in watery places — rivers, lakes, hot springs. If you look closely you can see what may be streaks of tears below her eyes. She was known to cry and wail to trick men to come into the water to get to know her better. Then she would drown them. In her left hand she may be holding a turtle. You can see the roundish shape of the shell, and the four feet. Because she couldn’t leave the water, Pa waip depended on turtles to travel out on land to do favors for her. But if we look closely we see the turtle has no head. So perhaps it’s not a turtle. Perhaps it’s a child and those four turtle feet are actually two human hands and two human feet. Sometimes Pa waip would grab children, and bite their heads off.

But she wasn’t only bad. Pa waip wasn’t only a threat. She could also help people learn to help and heal each other. Her powers were particularly helpful against diseases like epilepsy, which can cause seizures in people.

These images are called pictographs if they are painted on the rocks, or petroglyphs if they are pecked or carved into the rocks. For a long time, white people thought of them as art. That is, they assumed the people who made them did so for the same reason Europeans and Euro-Americans paint, draw, or sculpt—to make beautiful things that last, and that may be returned to when a person wants to feel the pleasures of beauty.

But archaeologists now understand the rock pictures have for a long time been used as sources of spiritual power, and are still used that way now. This allows us to think of the images as windows connecting past and present, and connecting the spiritual world with the material world at hand. Like churches, temples, or cathedrals of Europeans and Euro-Americans, they may be ancient, but they can still be used for their original purposes. This is different from simply admiring them for their beauty.

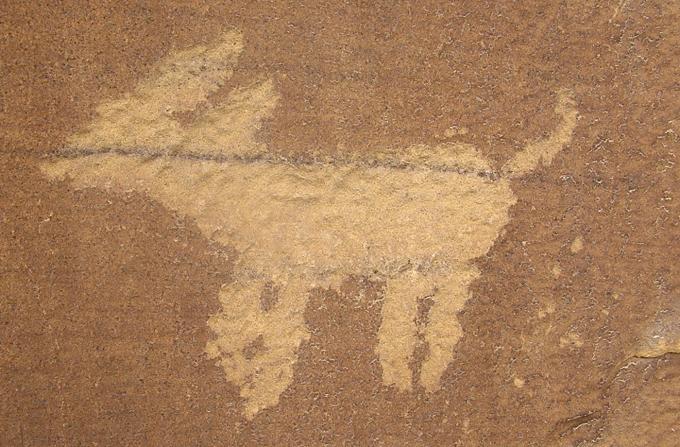

People went to the pictographs and the petroglyphs seeking the power they need for a successful life. Take for example the winged figure from the canyon of Torrey Creek, a tributary of the Wind River in central Wyoming. Before approaching a picture like this, the people would bathe in a stream or lake. Then they would wait in front of it, perhaps for days, without food or water, waiting and praying for a vision or a dream that would show them their power. (Vision seeking is common to all tribes, not just Shoshones.) If the vision instructed them to do so, they would make a new image on the rock to record what they had seen. The details would be useful for future visions—both for the original dreamer and for later vision seekers. Archaeologists and anthropologists more or less agree that image making of all kinds in Plains Indian cultures—on rocks, on clothing, on tipis and household goods — is connected with this same kind of vision seeking. (See Francis & Loendorf, pp. 24-26.)

The spear points the ancient people left behind them, and the arrow heads, or even the big nets used to trap wild sheep, show how they managed to survive in the material world, where people get hungry and need to eat every day. In the same way, the rock pictures are tools they used to help maintain a strong and confident sense of the world and their part in it. Confidence is as important to survival as eating. White people have been curious for some time about the rock images and their makers. In 1873, Captain William A. Jones of the U.S. Army led an expedition north from Fort Bridger on the new transcontinental railroad to Yellowstone Park. On the way he passed the Wind River and its tributaries in what’s now Fremont County, near Lander. He noticed rock images at four different places and reported on them in detail. Jones speculated that the first of these places “may have been used as a place of incantation by some Indian medicine-man.” But he was convinced Shoshone people did not make the images. To him they were only signs of the past — not places that had a spiritual purpose in the present. (Francis and Loendorf, 33-34)

In the late 1920s, an alert teenager named David Love left his family ranch on Muskrat Creek in a dry, remote part of Fremont County to attend the University of Wyoming. There he learned that a French archaeologist, Etienne Renaud, from the University of Denver, was surveying pictograph and petroglyph sites all over the high plains. Renaud had studied the ancient cave paintings of France and Spain, and was eager to see how ancient American images compared. Love knew of a spot packed full of Indian images. It was near his family’s ranch and called Castle Gardens, because its sandstone cliffs and cedar trees reminded people of castles with gardens growing on tops of the walls. Love wrote Renaud several times, and finally persuaded the archaeologist to come have a look. Renaud arrived in 1931 and returned the next year. He was so impressed by Love’s knowledge that he included Love’s descriptions in his own report.

Love’s favorite among the huge variety of images was a big, brightly colored turtle.

It was a foot high, nine inches across, with a circle drawn around it. The shell was divided into sections by incised lines, that is, lines cut deeply into the rock. The criss-crossing lines divided the turtle shell into about 50 different sections, each colored differently from the one next to it. Each of the turtle’s four legs was also divided by incised lines into sections — scales, they looked like. Each leg, Love noticed, had the same number of scales, and the corresponding scale on each leg was the same color. And each foot had five claws. The sections were green, yellow, or a reddish purple. The head was triangular, and red.

The length of the tail and the triangular head convinced Love the person who made the image knew turtles well, though turtles are rare in such dry country. The triangular head made Renaud believe it was a snapping turtle. He knew that snapping turtles along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers can grow to 120 pounds, and that turtles show up in many ancient Indian images in those valleys. (Love 690-692; Renaud, 9-16). Turtles show up too in ancient rock images throughout the high plains of the West. Clearly they’ve been important to people for thousands of years. Like people who become skilled in moving between the spiritual and material worlds, turtles move easily between water and land.

Renaud published his report in 1936. A few years later, Ted Sowers, an archaeologist working for the State of Wyoming, returned to Castle Gardens to photograph the turtle. He found the image gone, and only a hole in the rock left to show where it had been. Vandals had stolen it. What happened next is unclear, but the story goes that word went out among the people of Fremont county that the turtle had better turn up again if no one wanted their legs broken. The turtle did resurface, and was donated to the Wyoming State Museum in Cheyenne on Sept. 20, 1941. There it may still be seen. Its colors have dulled since Love first described it, but it’s well worth the trip.

For Love and Renaud, however, all these rock images were pictures of a past culture, made by the imaginations of people no longer among us. But in 1983, Mary Helen Hendry, a central Wyoming rancher, artist, and anthropologist (and longtime member of the Natrona County School Board) published a book, full of photos and descriptions of pictographs and petroglyphs in Wyoming. She photographed a site that had first been sketched by an army officer in 1882. But she noticed the headdress of one of the figures had been added to. Clearly, Indians were continuing to use the images in the late 1800s and early 1900s, perhaps down to the present. (Hendry, 12-14, cited in Francis & Loendorf, 34.)

Resources

Books and websites where you can learn more about Wyoming’s ancient people and the images they left behind them are listed below. Better, however, would be to visit the state museum for a look at the great turtle, and better still would be to visit the sites themselves. The three best are best are Castle Gardens, the Legend Rock Petroglyph Site, and the Medicine Lodge State Archaeological Site.

Field Trips

Northwest Wyoming

- Medicine Lodge State Archaeological Site near Hyattville.

- Legend Rock State Petroglyph Site, northwest of Thermopolis.

- Mummy Cave, west of Cody.

Northern Wyoming

- The Medicine Wheel, on US 14A between Lovell and Burgess Junction.

Northeast Wyoming

- Pictographs near Outlaw Canyon, west of Kaycee.

Central Wyoming

- Castle Gardens, 28 miles south of Moneta.

Southern Wyoming

- Saratoga Museum buffalo-kill diorama and related artifacts. And check at your own county museum for more information on local sites and ancient artifacts.

Secondary Sources

- Francis, Julie E. and Lawrence Loendorf. Ancient Visions: Petroglyphs and Pictographs of the Wind River and Bighorn Country, Wyoming and Montana. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 2002. An excellent and up-to-date scholarly overview, with many color photos and good black-and-white drawings of the rock pictures.

- Hendry, Mary Helen. Indian Rock Art in Wyoming. Lysite, Wyoming: privately published, 1983. Numerous black and white photos, and good drawings.

Love, J. D. “Petroglyphs of Central Wyoming.” Annals of Wyoming vol. 9 number 2 (1932): pp. 690-693. This is an excerpt of a paper Love first wrote when he was a student at Lander High School. - Jones, William A. Report on the Reconnaissance of Northwestern Wyoming Made in the Summer of 1873. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1874. His report, plus cool old fold-out maps. This book is in many Wyoming libraries.

- Renaud, E. B. [Etienne Bernardeau, born 1880] “Pictographs and Petroglyphs of the High Western Plains.” Archaeological Survey of the High Western Plains, Eighth Report. Denver: University of Denver Department of Anthropology, 1936. See pages 9-16 for his description of Castle Gardens, which relies heavily on Love’s.

- Check online for books in all Wyoming libraries including the one closest to you.

Online

- The Bureau of Land Management has a good overview of rock-picture sites on federal land in Wyoming on its page on Resources at Risk. This site is well maintained and up to date.

- For more on understanding and preserving ancient rock pictures, see a description of a summer course that Lawrence Loendorf offered a few years ago at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody.

- See also the Chief Washakie Foundation’s excellent overview of rock images in central Wyoming, taken from American Rock Art Research Association’s (ARARA) Exhibition Catalog from a conference in Wyoming in 2002. The images of the water-ghost woman and the winged figure are among ten shown and discussed in detail on this site. There’s lots of other good stuff on Wyoming’s Indians, especially Shoshones, on the Chief Washakie Foundation web site as well.