- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Red Ocher Mine At Sunrise

The Red Ocher Mine at Sunrise

How it was found

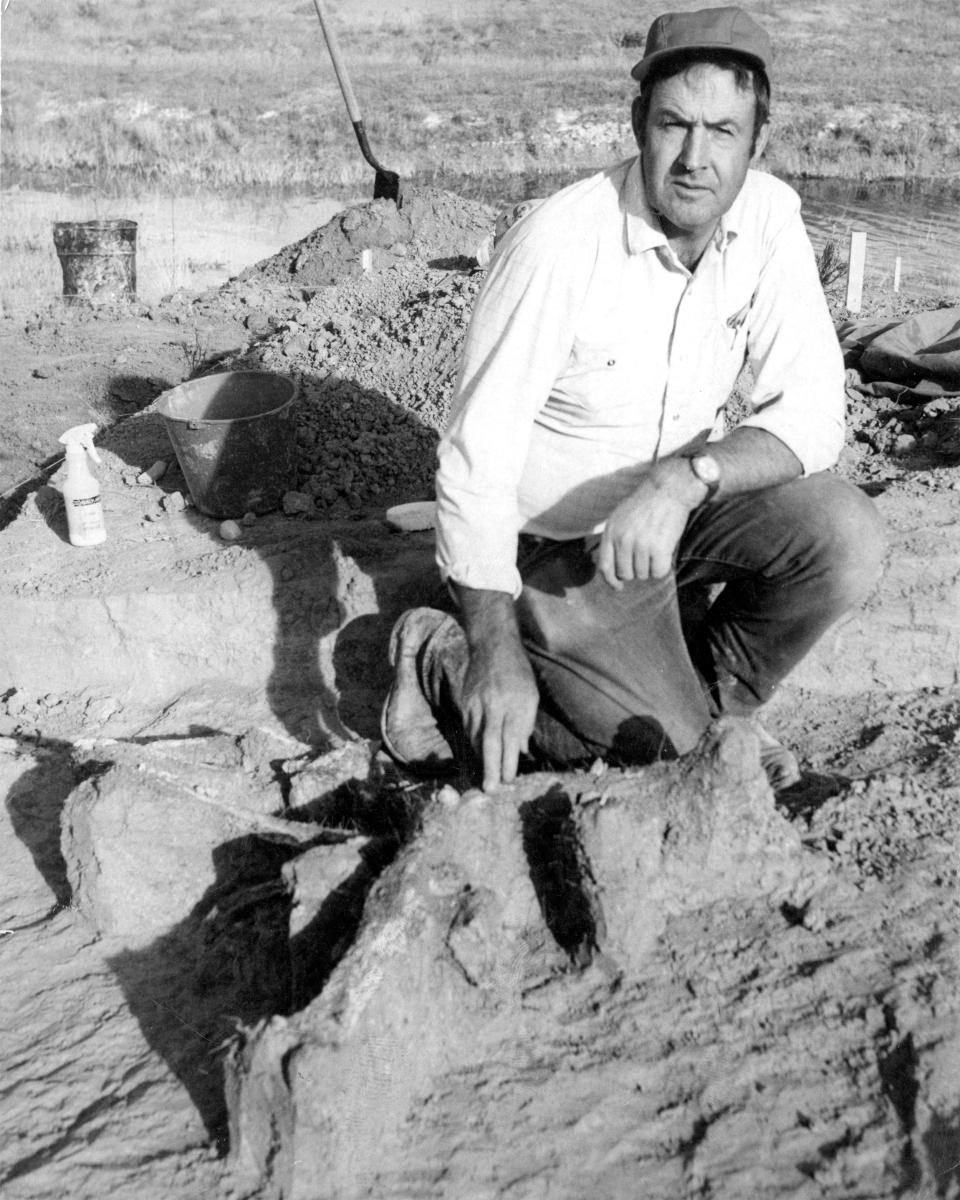

“Well, we had no idea what was going on, but I knew we had to do something really quick. I was ready to lay down in front of a probably D17 to stop that thing,” said George Frison, speaking of a large Caterpillar bulldozer. The year was 1986. He was then head of the anthropology department at the University of Wyoming.

Image

The occasion was a school reunion at Sunrise, Wyoming. Wayne Powars, an amateur archaeologist, had been a wrestling coach at Sunrise during the late 1930s and early 1940s. During his time at Sunrise, he had picked up a quantity of Paleoindian artifacts. The Paleoindian period dates roughly from 13,000 to 10,000 years before present (B.P.).

Sunrise was a company town in Platte County in southeastern Wyoming. It was owned by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I), which extracted around 40 million tons of iron ore from the site between 1898 and 1980. Close beside the mining pit was a small depression running downhill. It was below this depression that Powars had been gathering artifacts.

Powars returned to Sunrise for the 1986 school reunion intending to gather some more artifacts, only to discover that contractors with the Abandoned Mine Lands division of the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) were in the process of reclaiming the abandoned CF&I mine site. They were within a day or two of destroying the site where Powars had found artifacts.

Powars rushed to a telephone (maybe in Guernsey, Wyoming, five miles away) and called Dennis Stanford, who happened to be in his office. Stanford was an archaeologist and the director of the Paleoindian/Paleoecology Program at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. Stanford called George Frison, who was also in his office in Laramie. Frison called someone, maybe the governor, maybe Wyoming State Archaeologist Mark Miller. Someone called the DEQ. Meanwhile Frison hurried to Sunrise prepared take extreme measures, if necessary, to save the archaeological site from being shoved down the hill in the reclamation area.

The DEQ had conducted a survey of the CF&I mine but had not found the archaeological site. They were willing to modify their reclamation project and create a safe and stable situation for archaeological excavation.

Stanford and Frison had known about the possible archaeological site at Sunrise for several years. In 1981 Frison was completing a fellowship at the Smithsonian and working with Stanford on the book The Agate Basin Site. In walked Wayne Powars and dumped a sack of artifacts on the table, artifacts containing many tens of points and stone tools from the Clovis period (13,100 to 12,700 B.P.). A “normal” Clovis site, in Frison and Stanford’s experience, may yield 2 to 3 points or other artifacts. Powars’ collection, from one location, was unprecedented.

Powars explained that he had picked these up along the railroad tracks between Sunrise and nearby Hartville. Frison and Stanford walked the tracks but could find no artifacts. In 1986, Powars showed Frison exactly where he had been finding his artifacts, a railroad cut that allowed erosion from the adjacent ridge.

Stages of excavation

Excavations at the Powars II site came in three stages over nearly 35 years. First, Frison managed to organize a surface collection and small excavation before a dispute with the landowner in 1986 closed down further work. Second, from 2014 through 2016 Frison, archaeologist George Zeimens and others sifted through the material eroded down from the intact site. Third, Spencer Pelton, now the Wyoming state archaeologist, led crews excavating the site from 2017 through 2020.

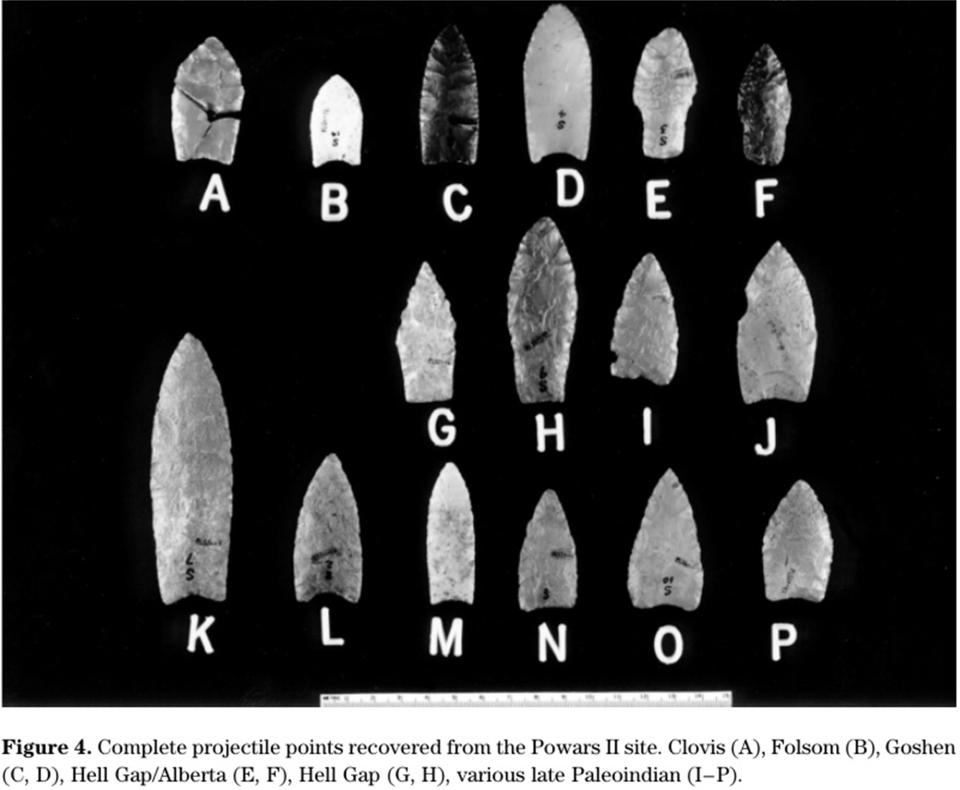

In the initial investigation, Frison confirmed that Powars II was an archaeological site dating back to the Clovis period. Mike Stafford, who later received his MA in anthropology from the University of Wyoming and went on to direct the Cranbrook Institute of Science in Michigan, analyzed the 1986 findings. He noted that the diagnostic projectile points ranged in age from Clovis to Late Paleoindian. When was Late Paleoindian? Not all sources agree on the number of years before present. Some sources mark the end of the Paleoindian period at 10,000 B.P. others as late as around 8,500 B.P. However, there is general agreement that the period ends with the Cody cultural complex. Also found were stone and bone tools, shell and bone beads and several pieces of bone bearing regularly placed, shallow cuts along the edge.

Stage two

In 2011, entrepreneur John Voight bought the town of Sunrise and the surrounding area; Voight supported and continues to support further explorations of the Powars II site. The second stage of discovery dates from that time. From 2014 to 2016 Frison, Zeimens and others screened about 200 tons of rock debris eroded downhill from the intact site above. This step was needed before they moved to the intact site.

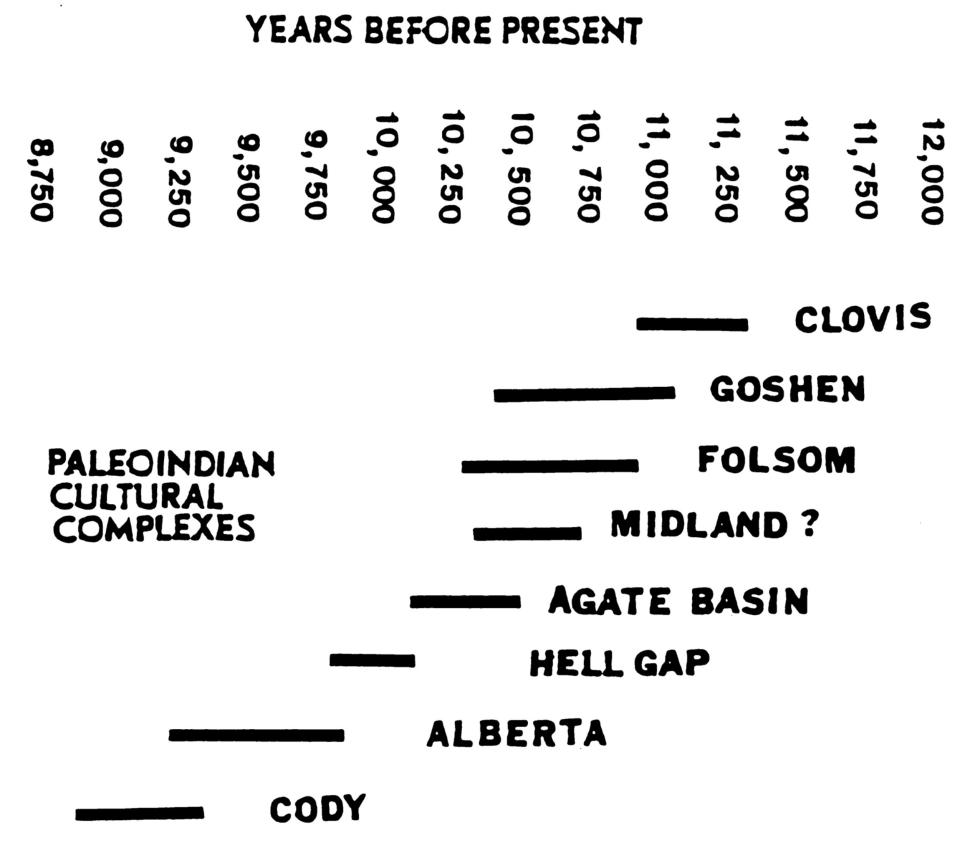

They recovered more than 7,000 artifacts. Radiocarbon dating of some poorly preserved bone fragments yielded a date of 10,000 years B.P. Clovis artifacts, including 53 points and 33 preforms, dominate. Preforms represent the final step before creating the actual point. Pelton later noted “Goshen, Folsom, Midland, Agate Basin, Hell Gap, and Alberta cultural complexes along with a large tool and flake assemblage that for the most part cannot be assigned to specific Paleoindian cultural complexes.”

All dates are B.P. and approximate: Goshen (11,010-10,030); Folsom (10,900-10,400); Midland (10,750-10,300); Agate Basin (10,500-10,100); Hell Gap (10,100-9,750); Alberta (9,900-9,250).

Stage three

Pelton had worked with the 7,000 flakes from the stage two assemblage. As a result, he was chosen to lead the third stage of exploration: the first controlled, systematic excavation in the actual intact portions of the site.

Pelton planned a 6 x 1 meter trench across the slope of the hill. The crews dug through successive layers of quarry tailings down to bedrock. They recovered thousands of Paleoindian artifacts: points, bifaces, preforms, spoke shaves and gravers, as well as tools used in the actual mining process. The stage two assemblage had mostly Clovis artifacts, whereas in the stage three group, Clovis is in the minority with no Folsom and Agate Basin spear points. Pelton inferred from this that there was lateral variation in quarry sites occupied by a given cultural complex.

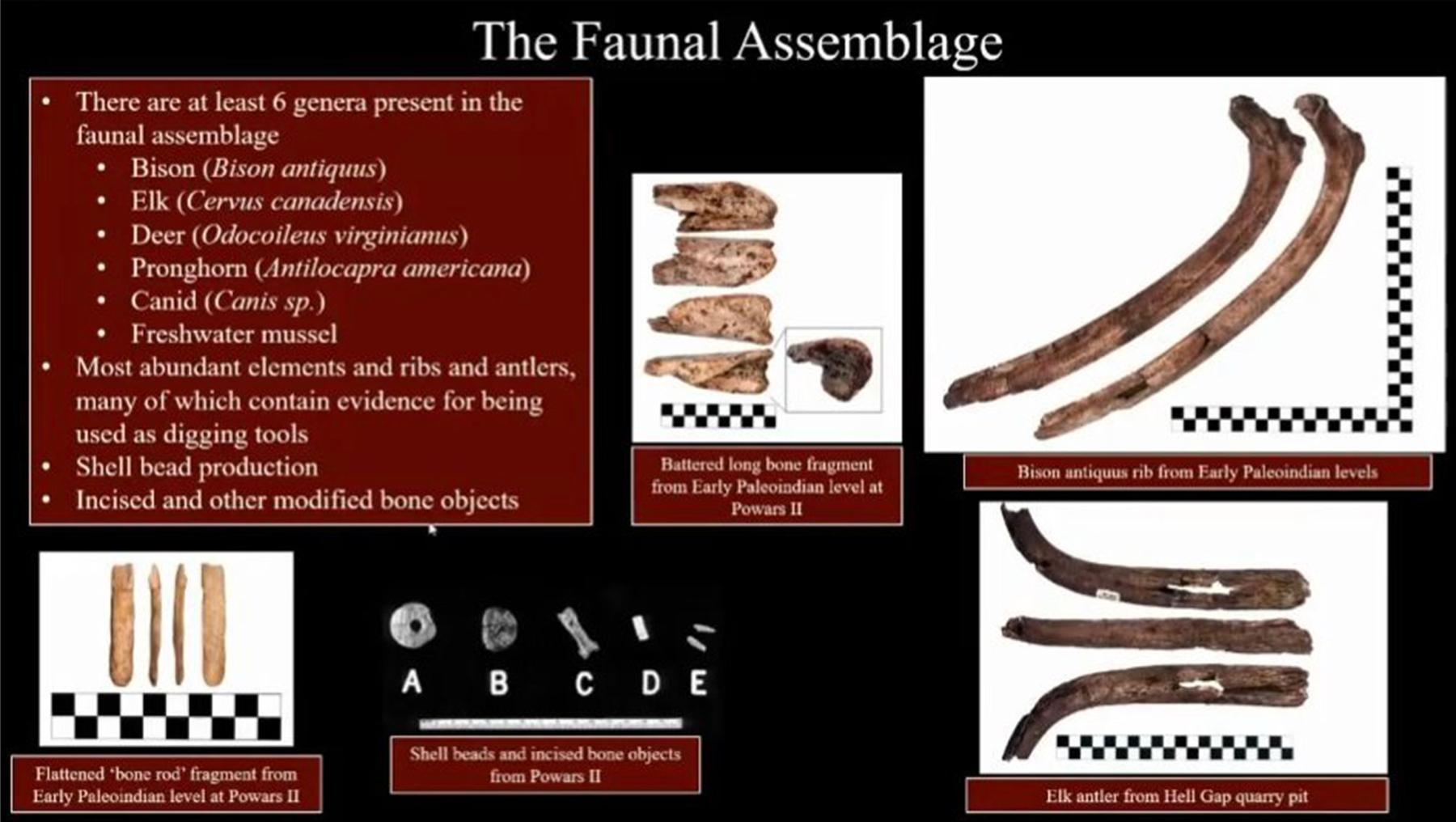

Stage three yielded faunal artifacts such as antler, ribs and other flat bones that could have been used as mining tools. They were from Bison antiquus, elk and deer.

Ancient ocher mining

It was Wayne Powars’ artifacts that initially caught Stanford’s and Frison’s attention. But the subsequent work provides a more detailed story. Mike Stafford, the graduate student, observed that the stage one Powars II assemblage suggests “a two-part cultural manifestation: a technological component resulting from the process of mining and processing ocher, and an ideological component derived from emic beliefs about the ocher source itself.” Emic beliefs are those determined from within the culture rather than superimposed by outsiders. We do not know what those beliefs might have been in this case that caused the deposition of many artifacts into the mine. But they persisted throughout all the Paleoindian mining activity, regardless of which cultural complex was involved.

Image

Though Powars II was primarily a red ocher mine, it is also a source for a distinctive chert and fine-grained quartzite. Not only were the Paleoindians digging red ocher, they were also producing points and digging tools on site. Evidence from stage three shows flakes from tool and point production mixed into the Clovis-period mine tailings. But the flakes are largely absent from tailings associated with mining by later people. From this archaeologists infer that the Clovis people were sitting on the edge of the mine making tools. If later groups made tools on site, it was apparently not right at the quarry pits.

Most of the points show signs of impact damage, meaning they were salvaged from killed animals. Some have been reworked. A new Clovis point is long and slender; reworked points retain the original width but are shorter due to the fashioning of a new tip. Some of the points could have been used again, yet they were deposited in the quarry pit. The abundance of artifacts suggests something more than just casual dropping of a used point or tool.

Diagnostic artifacts attest to the presence of Clovis, Goshen, Folsom, Midland, Agate Basin and Hell Gap cultural complexes, with all these peoples digging through the tailings of previous mining activity. Based on the artifacts, the mine was in use for 1,500 to 2,000 years. Beyond using identifiable artifacts to obtain dates, as in stages one and two, several bones and bone fragments from stage three yielded reliable radiocarbon dates, allowing estimates of the start of mine operation at around 12,800 years B.P.

Red ocher

The Powars II site may have been the source of red ocher found at many Paleoindian sites in the West. It may have been an annual destination for groups from around the West gathering to mine and socialize. Ocher from Powars II has been traced to places like nearby Hell Gap in southeast Wyoming, and the LaPrele Creek Mammoth site, 60 miles to the east.

Ochers are iron-bearing minerals of different colors depending on the iron compound present. Red ocher is called earthy hematite. Specular hematite is a shiny, silver-colored mineral that will make a red streak when rubbed on the body or other objects. Both are found in the Powars II quarry pits.

Image

The color red seems to have special, evolutionary significance for humans; the remains of early humans and their ancestors as far back as the inhabitants of Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, hundreds of thousands of years ago, have been associated with red ocher.

Many sources suggest that red ocher was used by the earliest people in the Americas, too. Archaeological sites have yielded ocher-stained weapons, bones of prey, burial artifacts and shells. Ocher can be used also as a preservative for wood and hide. It may have warded off insects and may have served as a sunscreen.

Though the artifacts tell only a limited story of life 13,000 years ago, we do know that, for example, the specular hematite from the Powars II site produces a high quality, deep red pigment when powdered. Grinding Powars II hematite in the presence of water creates the illusion that the rock is bleeding.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that a site where red ocher could be easily obtained should have attracted people for 15 or 20 centuries of mining—and living.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, which in part made publication of this article possible.]

Resources

- Elias, M., C. Chartier, G. Prévot, H. Garay, and C. Vignaud. “The colour of ochers explained by their composition.” Materials Science and Engineering B (February 2006): 70-80, accessed Dec. 5, 2023 at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237714974_The_Colour_of_Ochers_Explained_by_Their_Composition.

- Frison, George C. “Paleoindian large mammal hunters on the plains of North America.” Nov. 24, 1998. PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America), accessed Dec. 5, 2023 at https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.95.24.14576.

- “Hominid.” (definition) Cambridge Dictionary, accessed Dec. 6, 2023 at https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/hominid.

- Kuta, Sarah. “This 12,000-Year-Old Wyoming Quarry Could Be North America’s Oldest Mine.” Smithsonian Magazine, May 24, 2022, accessed Sept. 26, 2023 at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/wyoming-is-home-to-the-oldest-mine-on-the-continent-study-north-america-180980134/.

- Pelton, Dr. Spencer. “Mining Paint at the Powars II Site, Platte County, Wyoming.” Presented to 85th Annual Meeting of the Colorado Archaeological Society, hosted by the Indian Peaks Chapter. Sept. 26, 2020, accessed Dec. 5, 2023 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WUStU-B3KI4.

- _______________. “Pre-Clovis at Powars II.” Social Stigma. Field Notes No. 4. July 4, 2023, accessed Dec. 5, 2023 at https://socialstigma.substack.com/p/pre-clovis-at-powars-ii.

- Pelton, Spencer, George Frison, Marcel Kornfeld, Dennis Stanford, Danny Walker, and George Zeimens. “Further Insights into Paleoindian use of the Powars II Red Ocher Quarry (48PL330), Wyoming.” American Antiquity 8 (2018): 1-20, accessed Dec. 6, 2023 at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324617153_Further_Insights_into_Paleoindian_use_of_the_Powars_II_Red_Ocher_Quarry_48PL330_Wyoming.

- Pelton, Spencer R., Lorena Becerra-Valdivia, Alexander Craib, Sarah Allaun, Chase Mahan, Charles Koenig, Erin Kelley, George Zeimens, and George C. Frison. “In situ evidence for Paleoindian hematite quarrying at the Powars II site (48PL330), Wyoming.” PNAS.org, May 12, 2022, accessed Dec. 6, 2023 at https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2201005119.

- Stafford, Michael D., George C. Frison, Dennis Stanford, and George Zeimens. “Digging for the Color of Life: Paleoindian Red Ocher Mining at the Powars II Site, Platte County, Wyoming, U.S.A.” Geoarchaeology 18, no. 1 (2003): 71-90. Available to patrons via interlibrary loan at Goodstein Foundation Library, Caper College, Casper, Wyoming.

- Surovell, Dr. Todd A. “The First People and Last Mammoths of Wyoming.” Presented to Geologists of Jackson Hole. July 9, 2020. YouTube, accessed Oct. 3, 2023 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_HS_esmhd4.

- Tankersley, Kenneth B., Kevin O. Tankersley, Nelson R. Shaffer, Marc D. Hess, John S. Benz, F. Rudolf Turner, Michael D. Stafford, George M. Zeimens, and George C. Frison. “They Have a Rock that Bleeds: Sunrise Red Ocher and Its Early Paleoindian Occurrence at the Hell Gap Site, Wyoming.” Plains Anthropologist 40, no. 152 (May 1995): 185-194. Available to patrons at Natrona County Library, Casper, Wyoming.

- Wreschner, Ernst E., Ralph Bolton, Karl W. Butzer, Henri Delporte, Alexander Häusler, Albert Heinrich, Anita Jacobson-Widding, et al. “Red Ocher and Human Evolution: A Case for Discussion [and Comments and Reply].” Current Anthropology 21, no. 5 (1980): 631–44. JSTOR.org. Available to patrons at Natrona County Library, Casper, Wyoming.

- Wyoming PBS. “Rancher Archaeologist, Dr. George Frison - Main Street, Wyoming.” Sept. 15, 2014. YouTube, accessed Dec. 6, 2023 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_RI4O8Ua6w.

- Click here to watch a talk about the Powars II site given in 2020 by Wyoming State Archaeologist Spencer Pelton.

Illustrations

- The photo of George Frison is from the University of Wyoming Anthropology Department, with special thanks to Marcel Kornfeld.

- The image of the projectile points is from the article cited above by Mike Stafford and other scholars, “Digging for the Color of Life: Paleoindian Red Ocher Mining at the Powars II Site, Platte County, Wyoming, U.S.A.” Used with thanks.

- The timeline of cultural complexes is from George Frison’s article “Paleoindian large mammal hunters on the plains of North America.” Used with thanks.

- The image of the faunal assemblage is a screenshot from Spencer Pelton’s talk on Powars II, recorded in 2020. Pelton is Wyoming state archaeologist. Used with thanks.

- The images of the red hillside and the pile of red ocher are from the Sunrise Historic and Prehistoric Preservation Society. Used with thanks.