- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Rancher, Hunter, Archaeologist: George Frison o...

Rancher, Hunter, Archaeologist: George Frison of the University of Wyoming

Election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1997, George Frison Day at the Wyoming State Legislature in 1998, Paleoarchaeologist of the Century in 1999, finalist for the Wyoming Citizen of the Century award in 1999 – these honors and accolades only begin to embrace George C. Frison’s impact on today’s knowledge of the ancient history and people of Wyoming, on the fields of archaeology and anthropology, at the University of Wyoming and on several generations of students. In what is a uniquely Wyoming story, Frison—Doc as his students fondly called him—put the Wyoming region on the international map for Paleoindian research, established the University of Wyoming (UW) Anthropology Department as a premier research institution and bridged the very different worlds of Wyoming agriculture and academia.

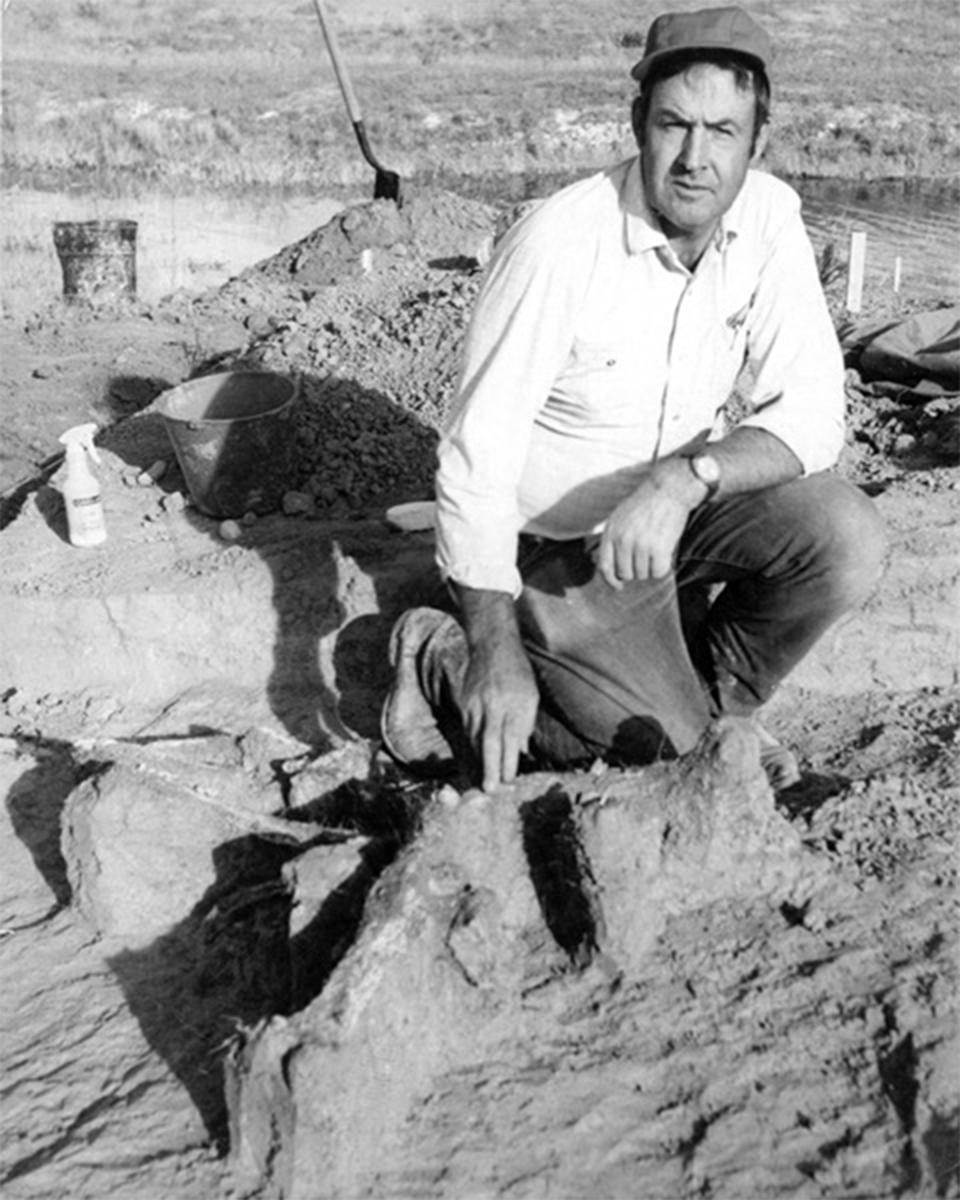

Image

Early life, service in World War II and education

Born on Nov. 11, 1924, in Worland, Wyoming, Frison was raised by his grandparents on the family ranch outside nearby Tensleep. His Depression-era childhood working the ranch exerted a lifelong influence on his study of the ancient past. His insatiable curiosity took root in days spent pushing cows and finding artifacts and, at an early age, he learned about the importance of wild game for keeping food on the table.

An entire chapter in his 2004 monograph Survival by Hunting is devoted to “The Education of a Hunter” as an essential element of Depression-era ranch life. He describes the complexities of laying trap lines for fur-bearing animals, protecting chicken coops and livestock from predators, snaring rabbits, the distress calls of prey and warnings of birdsong, the scent of elk, and tracking deer, pronghorn, mountain sheep and elk. This firsthand knowledge guided Doc’s later studies of prehistoric hunting and injected a great deal of common sense into his interpretations of hunting.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Frison was a 17-year-old high school senior. He wanted to immediately join the military, but his grandmother would not sign the necessary papers. After graduation in 1942, he enrolled at the University of Wyoming, enlisted in the U.S. Navy when he turned 18 and was sent to boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. After gunnery control system schools in Newport, Rhode Island and San Diego, California, Frison was assigned to the newly commissioned USS Navarro (APA-215), an attack transport vessel based out of San Francisco.

Frison’s sea duty, during which he was plagued with seasickness, took him to the invasion of Okinawa and around the Pacific before returning to San Francisco in 1946. He was offered a chief petty officer’s rank if he signed on for two more years. But the plains and mountains of Wyoming beckoned. He hitchhiked from San Francisco to Cheyenne and took a bus back home.

Returning to Wyoming, and practicing archaeology

The post-war years proved pivotal. Upon returning to Tensleep in 1946, he soon became reacquainted with June Glanville, the love of his life. They married that same year and adopted their daughter Carol in 1956. Their union lasted 65 years until June’s passing in 2011. The Frisons witnessed many changes in ranch life during these years: electricity, bottled gas for heat, four-wheel drive vehicles and tractors, and insulated boots. However, between infestations of insects and sheep ticks, the devastating winter of 1949-1950 and depressed livestock prices, ranch life was still a struggle, and the Frisons supplemented their income by outfitting.

Throughout this same period, Doc’s interest in archaeology deepened, beginning his transition from avocational artifact collector to professional archaeologist. Frison visited the professional excavation of the Horner site near Cody in 1951. He joined the Wyoming Archaeological Society in 1953. That same year, Doc and June located Spring Creek Cave on the western slope of the Bighorns near Tensleep and collected artifacts, coiled basketry, cordage and other rare perishable materials.

He took the collection to William Mulloy, then the only archaeologist at UW. Mulloy showed great interest and put Frison in contact with Marie Wormington at the Denver Museum of Natural History. Both mentored and encouraged him. Frison joined the Society for American Archaeology in 1956 and continued investigating several other sites as an amateur. But he began to question the ethics of artifact collecting for its own sake as his involvement with professional archaeologists grew.

In 1958, Frison took the Spring Creek cave collection to the 1958 Plains Anthropological Conference where he was badgered by Preston Holder of the University of Nebraska and Donald Lehmer of Dana College in Omaha to quit collecting and attend university to become a professional archaeologist. His first professional article, on Wedding of the Waters Cave near the mouth of Wind River Canyon south of Thermopolis, Wyoming, was published in 1962. In 1961, Mulloy invited him to the American Association for the Advancement of Science meetings in Denver, where Frison listened to professional papers and met with other noted archaeologists.

These meetings sealed the deal for a major career change. With June’s wholehearted support, on July 12, 1962, at the age of 37, Frison gave up ranching, and the family packed their belongings and headed for UW.

Studying archaeology in college

George Frison’s career as a student is legendary. Through summer school, previous credits, correspondence, by-passing introductory classes and overloading his class schedule, he graduated from UW with an undergraduate degree in 1964. From there, he headed to the University of Michigan. Under the tutelage of James B. Griffin and with Mulloy as principal investigator, Frison was awarded his first National Science Foundation grant and excavated the Piney Creek bison kill and camp site near Sheridan, Wyoming, in 1965. His dissertation established the prehistoric presence of the Crow in northern Wyoming and served as the foundation for much of his future research on bison procurement.

Image

Joining the University of Wyoming Archaeology Department, and garnering many awards

In May 1967, just under five years after leaving the family ranch, Doc earned his Ph.D. The family headed west back to Laramie, where he had accepted a faculty position in the newly formed UW Anthropology Department. At an age when most have become established in their careers, Frison was just getting started. He would go on to write an astounding 18 books and 115 articles, serve as president of both the SAA and Plains Anthropological Society, receive distinguished service and lifetime achievement awards from these and other professional organizations, the Golden Trowel Award from the Wyoming Archeological Society, and a host of other awards. In 1997, Frison was the first Wyoming native to be elected to the National Academy of Sciences, an achievement celebrated in both Washington, D.C. and by the Wyoming State Legislature.

Research

Through legislative lobbying by the Wyoming Archaeological Society, Frison was named as the first Wyoming state archaeologist less than six months after his return. He parlayed both his academic and state archaeologist positions with outside funding to embark on an ambitious research program focused on bison kills. Beginning in 1968, Doc investigated the Glenrock, Kobold, Ruby, Muddy Creek, Wardell and Vore sites, all in Wyoming. His studies demonstrated the sophisticated use of landscape to successfully manipulate bison herds to their demise.

Image

His intimate knowledge of livestock and wild game revolutionized faunal analysis. What were once considered useless piles of bones revealed information about herd structure, and whether a bone bed represented a single catastrophic kill or multiple kills over time and the season of the year in which a kill had taken place. His study of the use-lives of stone tools in 1968 still informs modern classification and typology. Throughout the 1970s, Frison also researched several other Paleoindian sites – the Casper, Agate Basin, Horner, Finley, Colby and Hanson sites. His work refined the original Northwest Plains and Paleoindian chronologies, and in 1978 he published his first synthesis of ancient Wyoming, Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains.

In 1973, Frison began another ambitious research program on the western slope of the Bighorn Mountains, centered on the deeply stratified deposits of the Medicine Lodge Creek site. Sparked by his amateur excavations during the 1950s, this work focused on the role of smaller game and plant resources for the ancient residents of Wyoming, defining what is now known as the Foothills Mountain Paleoindian adaptation. Frison was one of the first to recognize that hunting of mammoth and extinct species of bison was not the sole focus of all Paleoindian adaptations. He also established the differences between contemporaneous Plains and Mountain/Foothills peoples. His excavations formed the basis for additional research by several students.

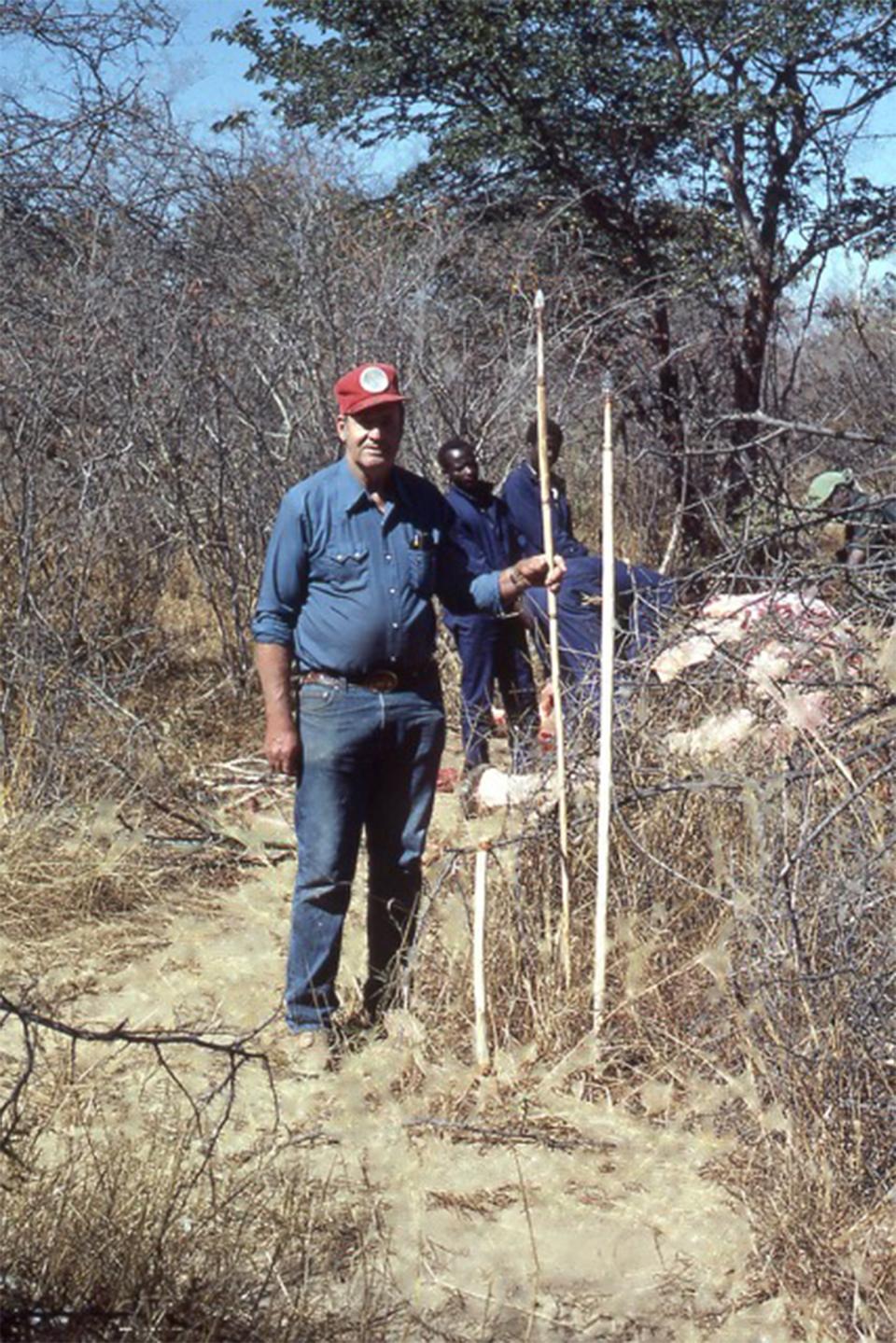

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Frison continued working on the Milliron site in Montana and the Hell Gap site in Platte County, Wyoming. A multidisciplinary approach, bringing in geologists, soil scientists and other experts, was a hallmark of his work and the foundation of today’s geoarchaeology. In a critical aspect of his work, he used experimental archaeology, including elephant and bison butchering with stone tools and spearing (dead) elephants in Africa with replica Clovis points made by Bruce Bradley.

Image

His ever-expanding professional network took him and June around the world to Africa, Europe, Russia, China, South America and back to the Pacific. Though he did not publish as extensively on these subjects, Doc extended his research to rock art, medicine wheels, cairns lines and trails, tipi rings, stone quarries, steatite sources and red ocher, as is reflected in the second edition of Prehistoric Hunters published in 1991. The third edition of this work, Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies, published in 2010 with co-authors Marcel Kornfeld and Mary Lou Larson, carried on these wider research interests.

Chair of the UW anthropology department

When Doc, June and Carol arrived back in Laramie in 1967, he joined a fledging UW anthropology department with three faculty members. Shortly after his arrival, he was appointed chair and quickly made several key hires or transfers to begin building a small, four-fields department—biological, cultural, archaeology and linguistics. By 1971, the first master’s degrees were awarded. The department continued to grow, based largely on Frison’s international research reputation. He freely shared research and publication opportunities with his students and his research interests served as the springboard for three generations of students, many of whom completed masters and doctoral degrees at institutions around the world and have gone on to successful careers in academia, with state and federal agencies, as historic preservation officers and consultants.

George C. Frison Institute for Archaeology and Anthropology endowment

Even after his formal retirement from teaching in 1996, Doc’s presence was strongly felt in the anthropology department. Except for his birthday, coincident with the Veteran’s Day holiday, he was a daily fixture in either his office or lab and continued researching and publishing until just a few months before his passing on Sept. 7, 2020. He was always available to students, faculty, visiting researchers and other archaeologists seeking his counsel.

His legacy began to be cemented when the endowment for George C. Frison Institute for Archaeology and Anthropology was established in 1996. Today, this fund supports many students and faculty. In retirement, he saw the development of a Ph.D. program. And in 2007, the anthropology department moved into its own dedicated building, with state-of-the-art classrooms, laboratories and curation facilities. On May 6, 2022, this facility was formally renamed the George C. Frison building, an honor rarely bestowed by UW.

In a quiet and unassuming fashion, George Frison spanned many different worlds and communities. His relationships with private property owners opened many gates to excavations on private lands. His ranching experience informed the world of anthropology and archaeology. He successfully bridged the worlds of research, teaching and university academia to build a widely recognized anthropology department. And he always maintained very close ties with the avocational community and the Wyoming Archaeological Society. Frison never forgot his roots, and his remarkable life leaves an indelible mark on the field of archaeology, the university and the state.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support which in part made this article possible.]

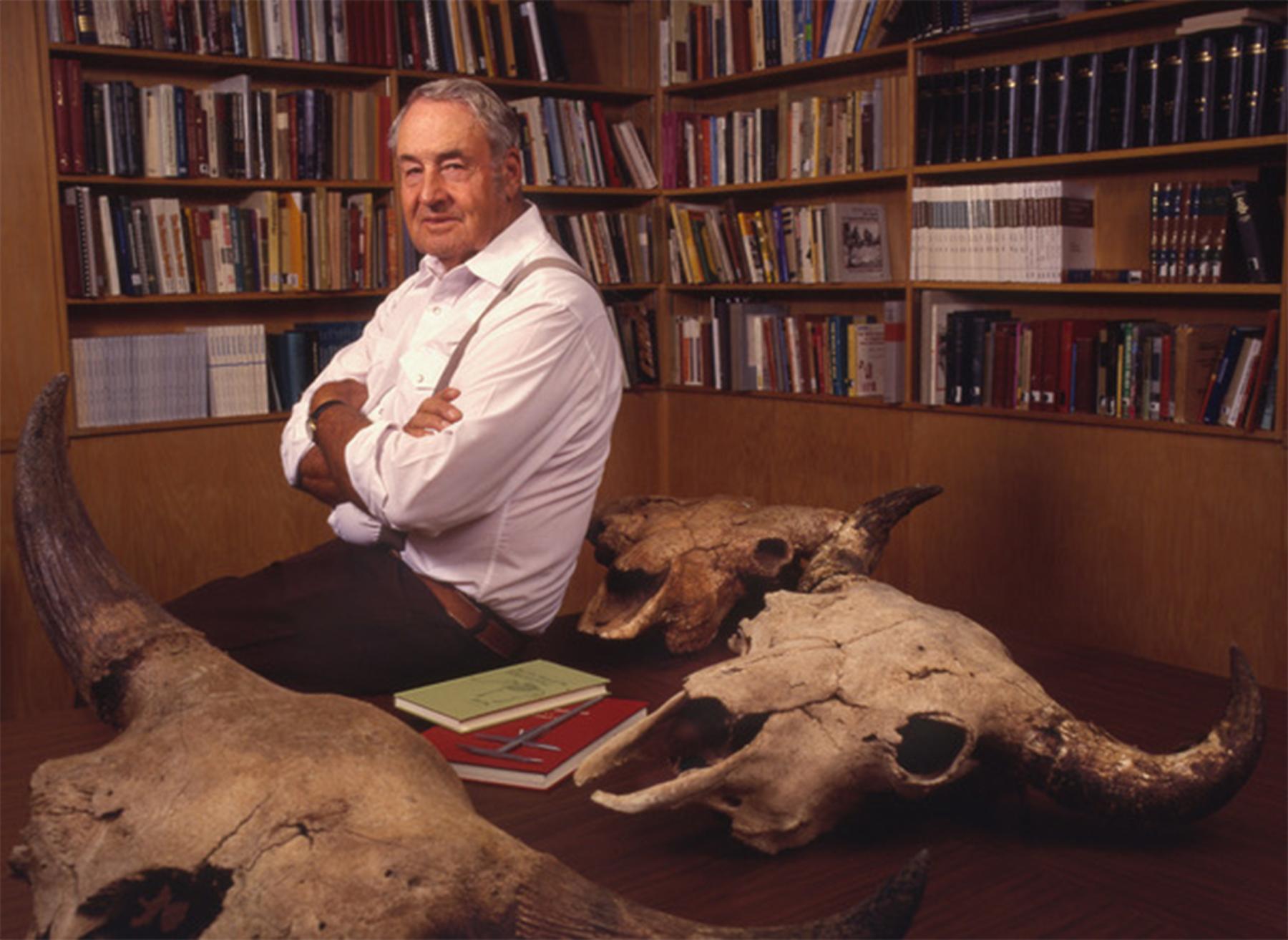

Image

Resources

Primary Sources

- Frison, George C. “A Functional Analysis of Certain Chipped Stone Tools.” American Antiquity 33, no. 2 (1968): 149-155.

- _____________. Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains. New York: Academic Press, 1978.

- _____________. Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains, 2d ed. New York: Academic Press, 1991.

- _____________. Rancher Archaeologist: A Career in Two Different Worlds. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2014.

- _____________. Survival by Hunting: Prehistoric Human Predators and Animals Prey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

- _____________. “Wedding of the Waters Cave: A Stratified Site in the Bighorn Basin of Northern Wyoming.” Plains Anthropologist 7, no. 18 (1962): 246-265.

- Kornfeld, Marcel, George C. Frison, and Mary Lou Larson. Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies, 3d ed. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, 2010.

Secondary Sources

- Anonymous. “George Frison Finalist in the Wyoming Citizen of the Century Competition.” The Wyoming Archaeologist 42, no. 2 (1998): xxiii-xxv.

- Francis, Julie. “Obituary, George Carr Frison, (1924-2020).” Plains Anthropologist 67, no. 261 (2022): 93-98.

- Kornfeld, Marcel. “George C. Frison, 1924-2020.” The SAA Archaeological Record 21, no. 5 (2021): 66-67.

Illustrations

- The first four photos are from the University of Wyoming Anthropology Department, with special thanks to Marcel Kornfeld.

- The photo of Frison in his office is from University of Wyoming Photo Services, with thanks to Ted Brummond.