- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Crook’s Powder River Campaigns of 1876

Crook’s Powder River Campaigns of 1876

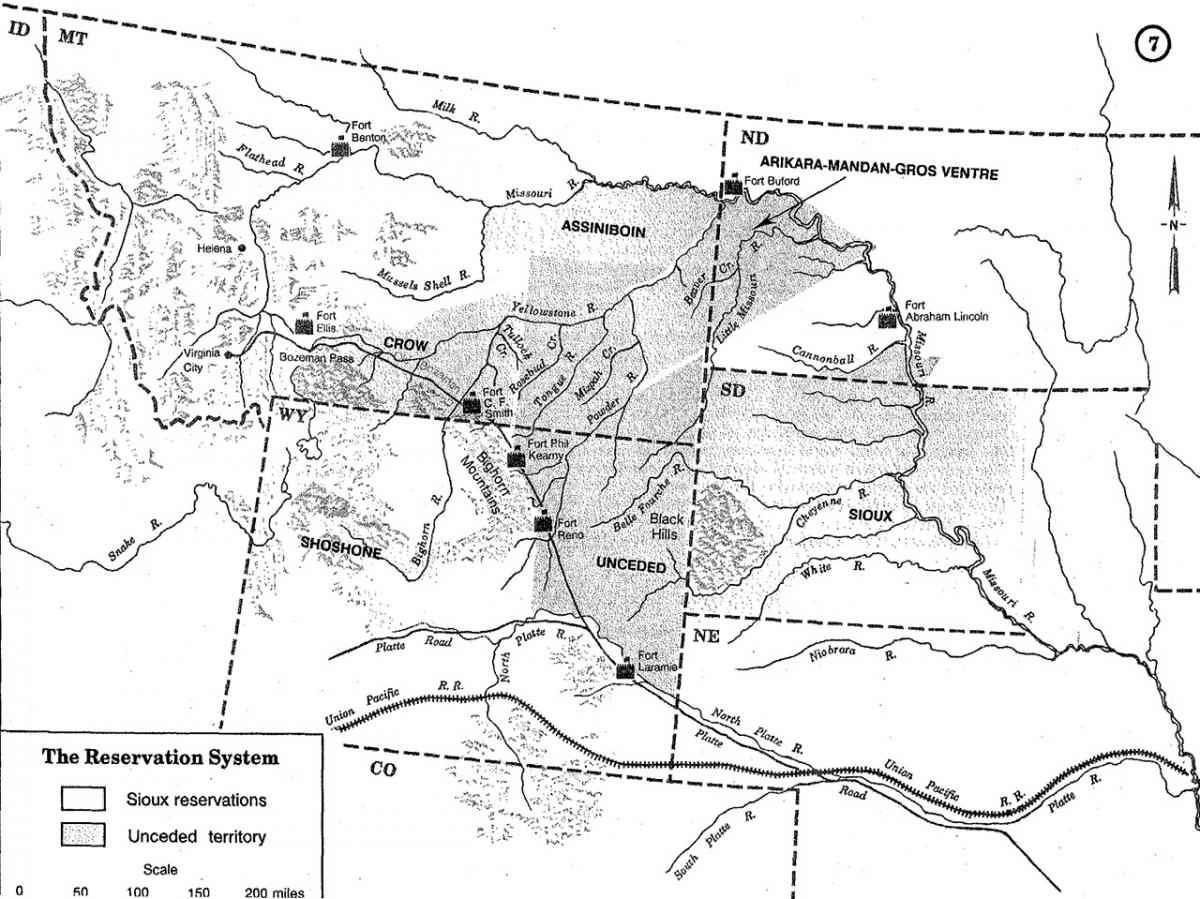

The discovery of gold in the Black Hills of Dakota and Wyoming territories in 1874 by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s expedition and the subsequent rush of fortune hunters deepened hostilities between the American Indians and whites. Though Custer’s exploration did not strictly violate the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which set aside lands for the tribes, the throng of prospectors searching the hills was not part of the bargain. The Indians resented the intrusion, and conflicts and skirmishes followed in short order.

The 1868 treaty had set aside lands for the Lakota Sioux in two categories—the Great Sioux Reservation, made up of most of the western half of Dakota Territory, and so-called unceded lands north of the North Platte and east of the Bighorns—essentially the Powder River Basin of northeastern Wyoming and southern Montana. Tribes were allowed to hunt and live in these unceded lands, where buffalo were still plentiful.

As tensions rose, however, the U.S. government officials decided the Indians needed to stay on the reservation lands and in December 1875 declared that all Indians not on those lands by Jan. 31, 1876, would be deemed hostile and subject to attack.

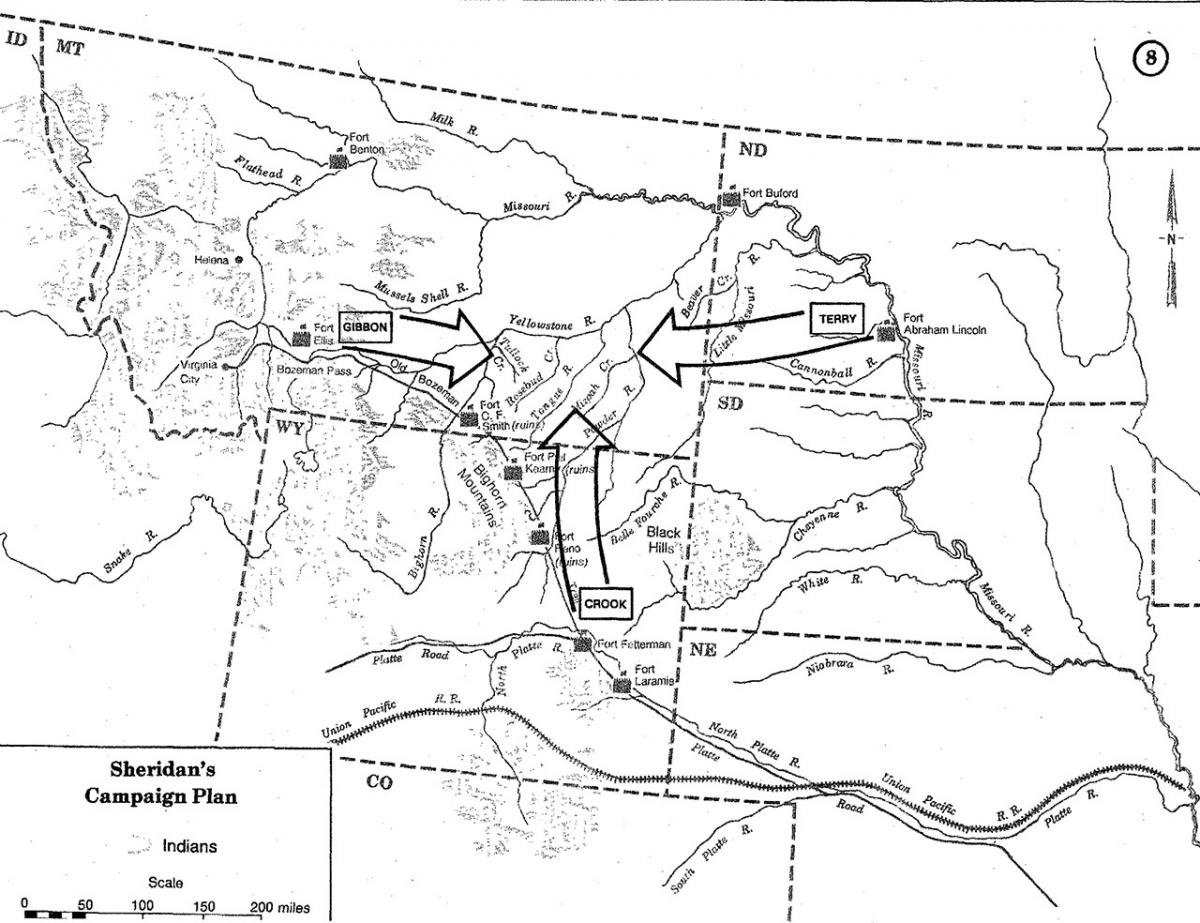

Chief of army operations in the West was Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, commander of the Division of the Missouri, which encompassed all of the Plains. Sheridan had previously been successful in campaigns in the 1860s to subdue Kiowa, Comanche and Southern Cheyenne by employing a multicolumn strategy and attacking the Indians in the winter, when their resources were needed most.

Sheridan ordered Gen. George Crook, who had been chosen in 1875 as the commander of the Department of the Platte, to lead three campaigns in 1876 from Wyoming’s Fort Fetterman to enforce the terms of the army’s order that “hostiles” return to the reservation. Crook used Sheridan’s strategies in these campaigns.

The first campaign, March 1876

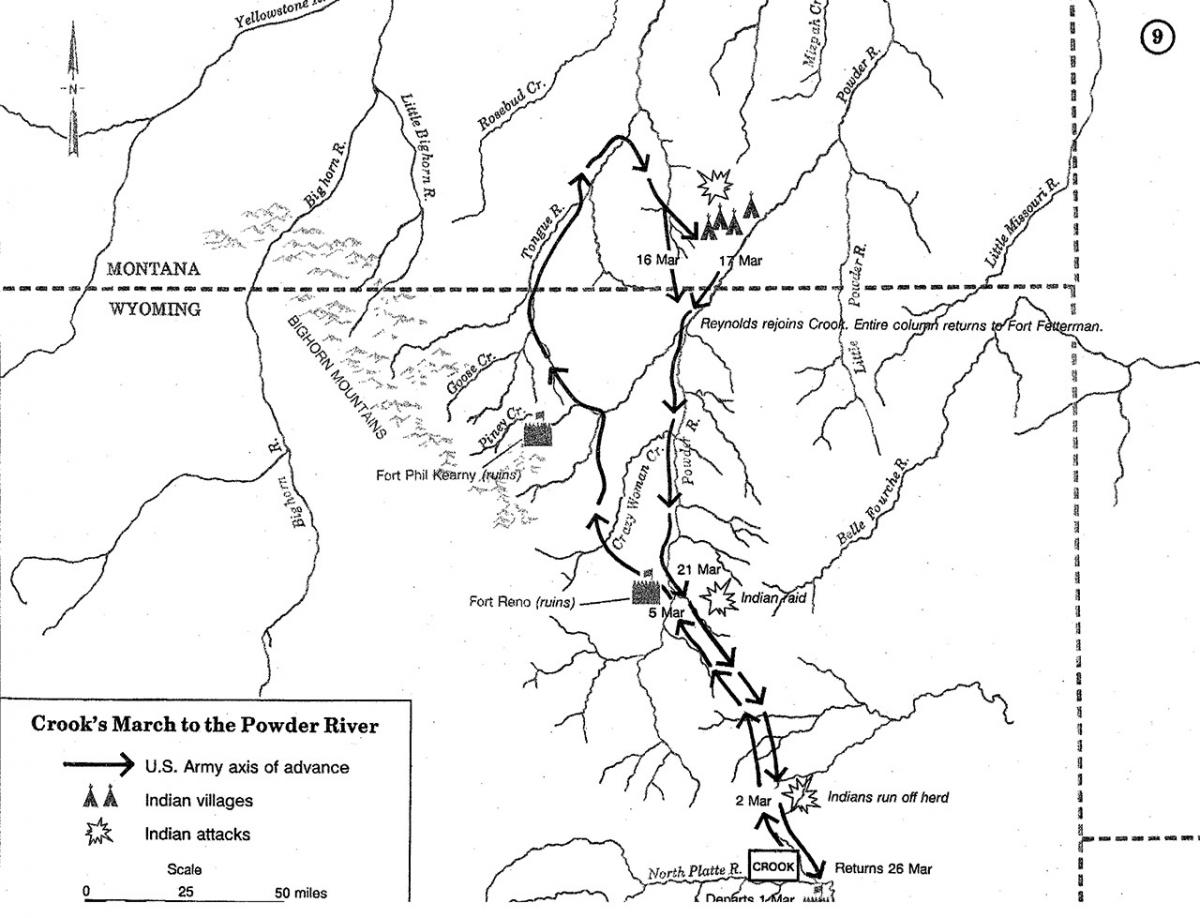

Snow had fallen the day before Crook and his command left Fort Fetterman on the sunny, cold morning of March 1, 1876, Capt. John G. Bourke of Crook’s staff recalled later. The troops marched north on the old Bozeman Trail toward the Powder River. The column, Bourke reported, included 10 full companies of cavalry, 86 wagons pulled by mules, three or four ambulances all filled with forage and a pack train consisting of five divisions of 80 mules each. Several Indian scouts accompanied Crook on the 90-mile trip as well.

On March 17, Crook and his men attacked an Oglala Sioux camp of Chief Crazy Horse on the Powder River in what is now southern Montana. Bourke recalled that the village “was bountifully provided with all that a savage could desire, and much besides that a white man would not disdain to class among the comforts of life.” Crook stayed behind “to protect the impedimenta” because the sight of pony tracks in the snow convinced him their position had been discovered.

Crook expected an attack on the supplies and remained near the place where the tracks had been found. The unit had traveled the Tongue River “to within less than one hundred miles of its mouth” and were headed toward the Powder River when they found the tracks. The general, who had a tender heart where mules were concerned, wrote, “Our pack mules’ shoes were so smooth I was afraid to take them into the rough country the village was likely to be in.”

He sent Col. J. J. Reynolds with troops to follow the tracks and find the village. Crook recalled in his autobiography that Reynolds attacked in the morning, but the village was situated under some bluffs, and the Indians gained the higher ground and drove Reynolds’ forces back. The retreat was conducted so hastily that the soldiers’ dead, and even perhaps one man who was severely wounded, were left in the hands of the Indians.

Troops suffered further from bitter cold and little food—a great disappointment for Crook, who had meat and furs at his disposal, but Reynolds had not sent word of their difficulties and so Crook had not sent the supplies he might have otherwise. Crook later brought charges of “misbehavior before the enemy” against Reynolds, who was found guilty and suspended from his rank and from command for one year.

The result of the battle was the opposite of what the military had hoped to achieve. Crook wrote, “After this affair the Indians became more openly defiant than ever.” He and his men returned to the supply base, Cantonment Reno, located at the Bozeman Trail crossing of the Powder River, few miles away from the site of the original and now defunct Fort Reno. Plans for a summer campaign were soon organized.

Stopped at Rosbeud Creek

On May 29, 1876, Crook’s troops again crossed the North Platte River at Fort Fetterman, but in ferry boats this time, a treacherous task because of the high waters of spring. Bourke described the departure, writing of “the long black line of mounted men stretched for more than a mile with nothing to break the somberness of color save the flashing of the sun’s rays back from carbines and bridles.” The wagons formed “an undulating streak of white” and “a puff of dust just in front indicated the line of march of the infantry battalion.”

They followed a route north similar to the one a few months earlier. This time, they marched toward the mouth of Rosebud Creek, a tributary of the Yellowstone north and west of the earlier attack on Crazy Horse’s people. And this time, Crook’s force would be joined by 86 Shoshone warriors, dispatched by their chief, Washakie, to help the army fight their old enemies, the Lakota Sioux.

Crook’s column was one of three converging on the tribes the government had deemed hostile. Gen. Alfred Terry led infantry troops out of Fort Abraham Lincoln in Dakota Territory and linked up with Col. John Gibbon leading more infantry from two Montana forts. Leading the 7th Cavalry, also out of Fort Lincoln, was Custer. But Crook never made any kind of rendezvous with the other troops.

On June 17, 1876, as they approached the Rosebud from the south, Crook and his men stopped and dismounted to allow their scouts to ride ahead and review their discovery of the enemy not far ahead. Crook recalled the cavalrymen took the bridles from their horses’ mouths to await the return of the scouts, not expected back for a while. Soon after, the hostile forces arrived and caught Crook’s troops by surprise.

At one time during the battle, Crook thought the hostile Indians had retreated, but they were instead keeping just ahead of the troops, ready to strike again. Crook withdrew, all the way back to Goose Creek, where Sheridan, Wyo., now lies, where his men could rest and nurse their wounds. More than a dozen men had been killed and about the same number of Indians, according to his estimate. Many were wounded on both sides.

The result was that Crook and his forces never linked up with Terry and Custer’s troops at all. Historian Martin Schmitt writes that had Crook been able to meet Terry as planned, the disastrous Battle of the Little Bighorn fought on June 25, 1876, would likely have had a much different outcome. The loss at the Rosebud, he wrote, “rankled in Crook’s memory all his life, and he steadfastly insisted that had the battle progressed according to his orders, it would have ended in real triumph.”

The Dull Knife Fight

The general’s autobiography ends after the Rosebud, but Crook’s 1876 campaigns were not yet over. Schmitt explains that Crook wanted to continue the Yellowstone Expedition to strike the Indians in winter and gain control of Crazy Horse. Crook’s superior, Lt. Gen. Sheridan, disbanded the expedition but relied on Crook’s expertise to gather the Sioux led by chiefs Red Cloud and Red Leaf at Camp Robinson in northwestern Nebraska in late October. Schmitt reports that when these Indians were surrounded and disarmed there, the military’s objective for the Yellowstone Expedition was achieved.

In November, Crook again headed into Powder River country. Winter conditions tried the patience of his soldiers during this campaign but at the same time contributed to the defeat from which Dull Knife’s Northern Cheyenne would never recover. On Nov. 25, 1876, five months to the day after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Crook sent more than half of his men—1,100 strong, including about 100 Pawnee scouts—under Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie to attack Dull Knife’s village on the Red Fork of Powder River, west of present Kaycee, Wyo.

Historian Sherry L. Smith, whose great-grandfather served under Crook during this campaign, quotes Crook from John Bourke’s diary. According to Bourke, Crook said, “We don’t want to kill the Indians, we only want to make them behave themselves.” His plan was to force the tribe’s surrender by destroying its economy—scattering the Cheyenne pony herds, burning their lodges and destroying their possessions—and this he managed to do.

The soldiers struck at dawn; they found a narrow entry through the natural shelter of bluffs and ridges and bountiful cottonwoods and willows that provided protection to the village along the creek. The troops discovered some items of the Indians—a necklace made of human fingers and recognizable scalps, for example—that aroused the soldiers’ hunger for revenge for the deaths of Custer and his men. Historian Robert Utley describes the devastating result: “Forty Cheyenne died, and the rest watched helplessly from the bluffs as the soldiers burned their tipis, clothing, and winter food supplies. That night the temperature plunged to thirty below zero. Eleven babies froze to death at their mothers’ breasts.”

Lt. John McKinney was the only officer killed in this battle; he was 29 years old. Cantonment Reno was renamed Fort McKinney in his honor.

Crook’s later career

Crook continued his service in the Department of the Platte, stationed at Omaha. He served as commanding general in that department until 1882, until he returned to Arizona where he had served in the 1870s, to lead campaigns against the Apache. In 1886 he returned to Omaha until President Cleveland promoted him to major general and he moved to Chicago, where he served as commanding general of the Military Division of the Missouri.

Bourke recalled that Crook “manifested all through his life the liveliest interest in the preservation of the larger game of the Rocky Mountain country, and, if I mistake not, had some instrumentality, through his old friend Judge Carey, of Cheyenne, now United States Senator, in bringing about the game laws adopted by the present State of Wyoming.”

Crook died at age 61 on March 21, 1890, of heart failure. Sioux Chief Red Cloud, according to Schmitt, “expressed the thoughts of his people to Father Craft, a Catholic missionary: ‘General Crook came; he, at least, had never lied to us.” The general was first buried in Maryland; his remains were later relocated to Arlington Cemetery. Crook County, Wyo., is named for him.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Bourke, John G. On the Border with Crook. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2014, 254, 269-282, 291, 487-488

- Schmitt, Martin F., ed. General George Crook: His Autobiography. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma, 1986, 189, 191, 193, 195, 198, 289, 300-301

- Smith, Sherry L., and William Earl Smith. Sagebrush Soldier: Private William Earl Smith's View of the Sioux War of 1876. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989, 45-88.

- “Fort Laramie Treaty, 1868.” New Perspectives on the West, PBS. The full text of the treaty, accessed April 18, 2014, at http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/resources/archives/four/ftlaram.htm.

Secondary Sources

- Ellis, Richard N. “Sheridan, Philip Henry.” In The New Encyclopedia of the American West, ed. Howard Lamar. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998, 1042-1043.

- Lebsack, Nicole. “Crook County, Wyoming.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed April 17, 2014, at /encyclopedia/crook-county-wyoming.

- National Park Service. “The Expedition against the Indians.” Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, accessed April 19, 2014, at http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/hh/1a/hh1b.htm.

- Robinson, Gerry. “The Dull Knife Fight, 1876: Troops Attack a Cheyenne Village on the Red Fork of Powder River.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed April 15, 2014, at

- /essays/dull-knife-fight-1876-troops-attack-cheyenne-village-red-fork-powder-river.

- Schmitt, Martin. “Crook, George.” In The New Encyclopedia of the American West, ed. Howard Lamar. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998, 275.

- Utley, Robert M. The Indian Frontier 1846-1890. Rev. ed. Albuquerque, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press, 1984, 175-179.

For further reading and research

- Cozzens, Peter. “Ulysses S. Grant Launched an Illegal War Against the Plains Indians, Then Lied About it.” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2016, accessed March 12, 2020 at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ulysses-grant-launched-illegal-war-plains-indians-180960787/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery. A look at the dissembling, chicanery and coverup in the Grant administration and the U.S. Army leading up to and away from the campaigns of 1876.

Illustrations

- The portrait of Crook in the 1870s is from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The maps of the forts, trails and movements of Crook’s campaigns in 1876 are from FortWiki. Used with thanks.

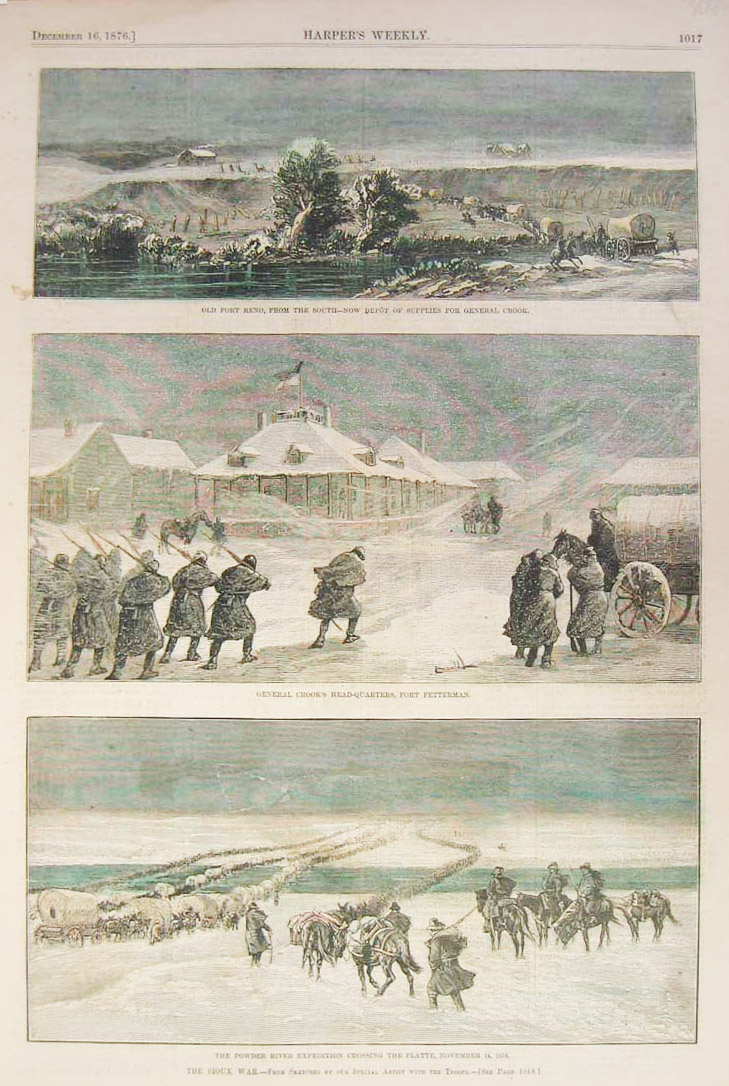

- The trio of tinted Harper’s Weekly illustrations from December 16, 1876 is from Prints Old and Rare. Used with thanks.