- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Who Was Lucretia Marchbanks? From Slavery To Ra...

Who was Lucretia Marchbanks? From Slavery to Ranch Life in the Black Hills

After a lifetime of serving others, first as an enslaved woman in Tennessee and then as one of the best cooks in the mining towns out west, Lucretia Marchbanks retired to a homestead on the western edge of the Black Hills in Wyoming. That’s when she took up ranching. As a teenager she had been taken in bondage across the continent to California during the greatest of all American gold rushes. She and several siblings spent the decade after the Civil War in Colorado gold camps. But it was in Deadwood that she parlayed her worldly experiences into success and fame. Independent and unmarried, she supported herself first as a cook, then a boarding house manager, and later owned her own hotel. She was twice voted the most popular woman in the Hills. Financial success made her move to Wyoming possible.

Image

Who was Aunt Lou?

Marchbanks was one of the best-known figures in the Hills, recognized far and wide as “Aunt Lou.” Early on, when her reputation filtered back to the East Coast, a perplexed New York newspaper editor queried, "Who is Aunt Lou?" The Black Hills Daily Times responded on Dec. 12, 1881,

We'll Tell You Who She Is.

Aunt Lou is an old and respected colored lady who has had charge of the Superintendent's establishment of the DeSmet mine as housekeeper, cook and the Superintendent of all the Superintendents who have ever been employed on the mine. Her accomplishments as a culinary artist are beyond all praise. She rules the ranch where she presides with autocratic power by divine right, brooking no cavil or presumptuous interference. The Superintendent may be a big man in the mine or mill, but the moment he sets foot within her realm he is but a meek and ordinary mortal. Aunt Lou is believed to be the first lady of color who set foot in the Black Hills. Her check is good for all she may sign for, and no one stands higher in the community than the sable of the DeSmet.1

But questions remain: Who was she? How did she see herself? What kind of life did she, as a female and racial minority, experience in the community she helped shape? How did she improbably become a prominent figure in Black Hills history?

The first White woman in the Black Hills

Even though her skin was “black as the ace of spades,”2 Marchbanks identified so completely with the dominant White, Euro American culture that, late in life, she claimed to have been the first White woman in the Black Hills.3 Her statement was not unique. George Bonga, who was “so black that his skin glistened,” described himself as one of the first two White men in the fur country of Minnesota. Though frontier race relations were complex and Black Americans were unarguably second-class citizens, Marchbanks, Bonga and their contemporaries typically recognized only two categories of people: Indians and “us.” Marchbanks and other Black American pioneers were part of, not distinct from, the Euro-American cultural front implementing the nineteenth century philosophy of Manifest Destiny4 while engaged in conquering the landscape and native inhabitants of the West. American Indians regarded the racial situation in much the same way, sometimes calling Black Americans “black White men.” Though Marchbanks’ skin was black, most everyone recognized her as being “culturally White.”5

And in fact, Marchbanks was of mixed African and European ancestry. She was born into slavery in Putnam County, Tennessee, in 1832 or 1833. Her enslaved father was the son of a White man and one of his enslaved women. Her grandfather thus owned his own son (Lou’s father), plus his daughter Lucretia and about 10 of her surviving siblings. She never attended school, never learned to read or write, and was trained as a housekeeper and kitchen slave. When she was in her teens her grandfather gave her to his youngest White daughter who took her to California during the gold rush.6 Sometime prior to the Civil War Lou was taken back to her childhood home in Tennessee.7 After the Civil War, several of Lucretia’s siblings moved to the booming Colorado gold camps where she soon joined them.8

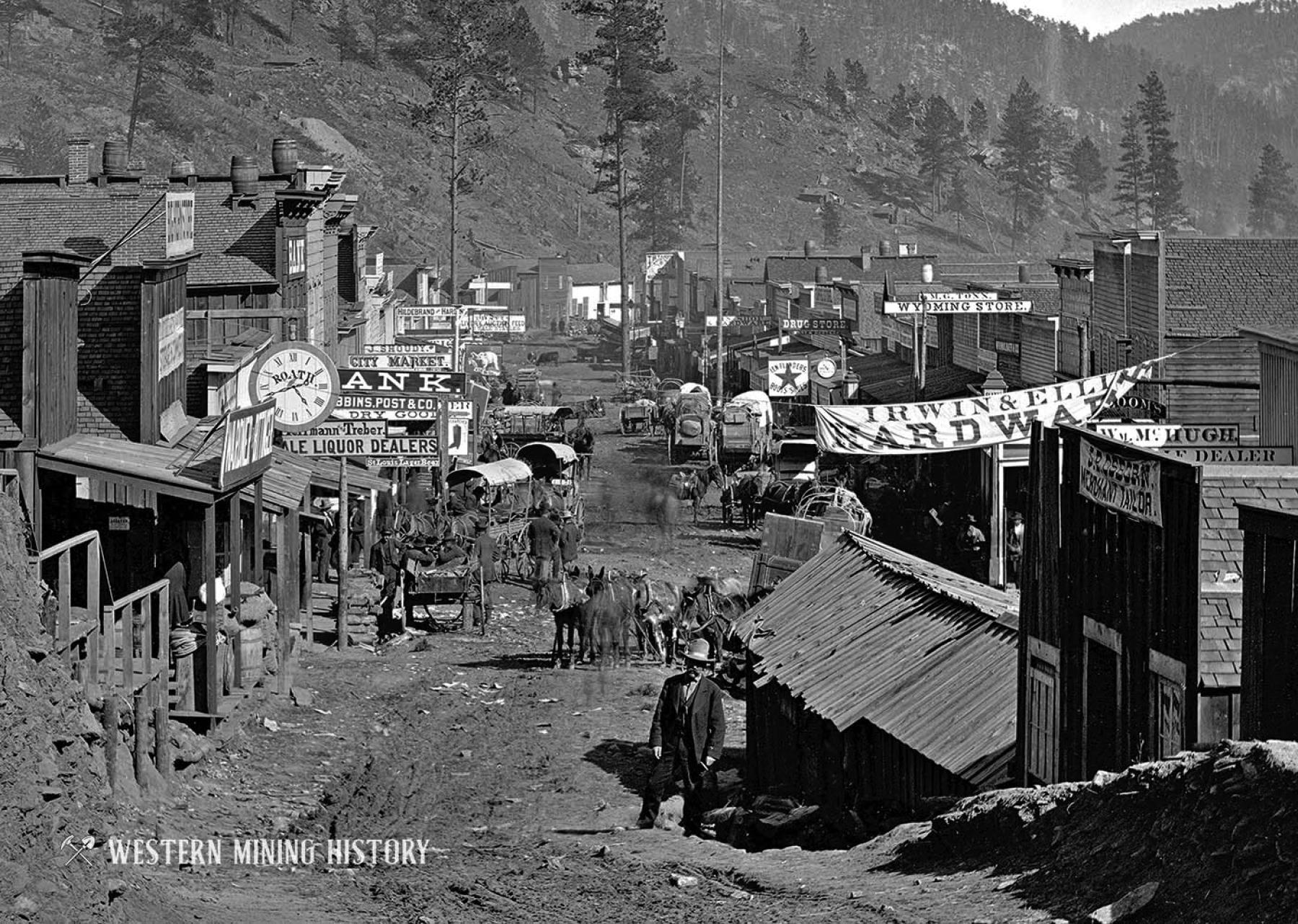

Seeking gold in Deadwood

By 1876 she joined the vanguard of the Black Hills gold rush. On the dangerous trail north her party’s horses were stolen by bandits who plagued the area. They recovered their stock with the help of a man Marchbanks identified as Wild Bill Hickock. Though appreciative, she otherwise had little use for him and later remembered the famous gambler and gunfighter as a rounder and broken-down gambler who ate in her restaurant several times.9

When Marchbanks first stepped down into the dirty streets of Deadwood she found a crowd that differed little from those she had seen in California and Colorado. They were all after gold but Marchbanks had no intention of becoming a miner. The few women who lived in mining districts typically worked in service industries supplying the various wants and needs of the miners in exchange for gold. Providing meals and lodging was one of the most important such efforts. Lou promptly secured employment as a cook in the prominent Grand Central Hotel.10

The most popular woman in the Black Hills

Maintaining Victorian feminine decorum wherein women were expected to be quiet, submissive, and retiring was sometimes a challenge in the fearsome violence of that first summer. A Mexican paraded the gruesome head of a dead Sioux Indian around town until his riotous debauch took him to Lou’s domain in the Grand Central where he,11

"with a chip on his shoulder, came in the restaurant and boasted that he had killed an Indian and perhaps let it be known that he wasn't above adding another notch to his gun. The customers were nervous as they sipped their coffee, keeping a watchful eye on the killer who strutted about the place. Aunt Lou decided he wasn't exactly an attraction to the establishment and confronted him with a gleaming knife in hand and fire in her eye. The Mexican eyed the keen blade, he looked at Aunt Lou's face and decided he had urgent business elsewhere ... pronto."12

Marchbanks, nicknamed Mahogany, was no ordinary boomtown hash slinger. Though the hotel’s guest rooms were crude, the board on her table earned fame. People were willing to pay higher food prices at the Grand Central to enjoy the results of Lou’s efforts over the stove which set the culinary standard for the whole town. A competing hotel, the Overland, advertised that their kitchen was "presided over by a clean, neat, and intelligent white man."13

In mid-September 1876, General Crook and his staff, just arrived after an exhausting season in the field chasing the killers of General Custer and the 7th Cavalry, obtained “quarters in the best hotel of the town: ‘The Grand Central, Main Street, opposite the Theatre … the only first-class hotel in Deadwood City.” Crook’s adjutant, John G. Bourke, commented that the food was “decidedly better than one had a right to look for” in such a community. Marchbanks subsequently cooked at the Wagner Hotel and later was offered a still better position in the Golden Gate Hotel. During these years, she became renowned among the camps for her wizardry in the kitchen and for her noble character. She was an employer’s dream and it was said that she "observed the principles of right living: industry, frugality, honesty and love of mankind.”14

Image

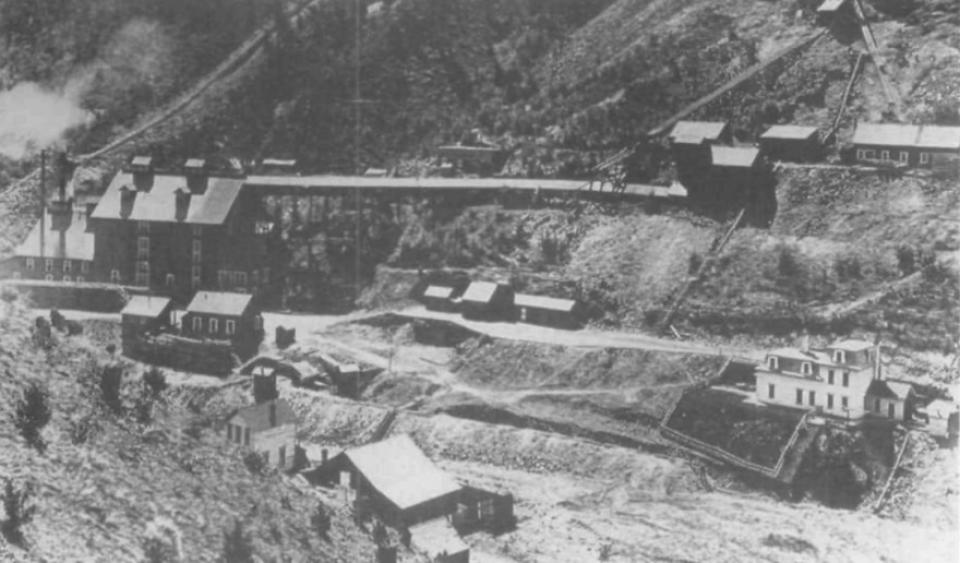

An offer of better wages convinced Marchbanks to manage the boarding house and cook for the executive table at the headquarters of the fantastically rich DeSmet Mine. She worked there for four successive superintendents at the impressive salary of $40 a month.

In 1879, the illiterate ex-slave’s fame took a tremendous leap which she could not have imagined when she was a girl growing up in bondage. The community held a fund-raiser to build a church which included raffling a diamond ring to determine the most popular woman in the Hills. The miners rallied to support of their “sable benefactress." Nearly 2,000 votes were cast at 50 cents each and Lou won handily with a total of 652 and took home the diamond. In a similar contest she won a valuable silver service.15 She once baked such a marvelous mince pie for a man that he bought her a silk dress. The best-known photo of Marchbanks was taken Nov. 8, 1881, while she was wearing the dress.16

Her own venture

Nevertheless, Lou had wearied of constant labor for others and opened a private boarding house that she christened The Rustic Hotel. The paper reported her as “doing well and looks twenty years younger.”17 The venture was successful and described as being “over run with custom,” a situation the newspaper reporter predicted was likely to continue “as long as she provides such dinners as we partook of.”18

Lucretia Marchbanks was not the only Black American businessperson in the Black Hills. Edmond Colwell ran a saloon in Deadwood in 1880. In Sturgis, a Black man named Abe Hill owned a saloon which catered to Black buffalo soldiers at Fort Meade. Black miners played a major role in fueling the flames of gold rush excitement when their early and rich discoveries were advertised at the Centennial Exposition.19

Through the years of gold rush excitement, racial harmony and racial tension in the Black Hills, Lucretia Marchbanks’ personal reputation grew. Her nickname, “Aunt Lou,” is evidence of broad acceptance. Admirers often associated Marchbanks with their own mothers. It was said that Aunt Lou guarded the human flotsam and looked after the health, comfort and welfare of the miners as if she were their natural mother. One woman went so far as to say that Aunt Lou was like a mother to all the women in the Hills: she delivered their babies and nursed young and old when they were sick or hurt. This familial warmth and responsibility contributed in part to her nickname, "Aunt Lou."20 At the same time, “Aunt” was a flag signifying that this Black woman is deferential and not threatening to Whites. Even so, some people could not accept that a woman of Lou’s caliber and success could be Black. On one occasion, when asked if she had any White blood in her veins, she responded, "No child, all I evah seen was red."21

She missed not having any real family close by. A sister, Martha Ann, called Mattie, finally joined her in 1885 but did not stay long. She married Harry Marshall, a Black American barber at Lead City and soon the couple moved to Pueblo, Colorado.22

Ranching in Wyoming

That same year, Marchbanks astonished everyone and declared that having spent a half century slaving in the kitchen, she was tired of cooking and cleaning for the hordes even in her own establishment. By June, just nine years after the Battle of Little Bighorn, she had acquired a ranch and cattle just across the border in the western Black Hills between Beulah and Sundance, Wyoming Territory. She registered her own brand, an "ML" burned onto her horses' left hips.23 In 1890, only 541 Black people lived in all of South Dakota, while Lou became one of 922 in Wyoming. According to census data, by 1900 there were only two Black farms or ranches in Wyoming, though research by this author indicates that figure is too low. She was a deeded landowner on equal footing with the grandfather who had enslaved her as a child.24

Marchbanks was well-liked by local families and played an intimate part in their lives. Her neighbors often called upon Aunt Lou to act as a midwife and she delivered babies for many families. At least one White child, Annie Lucretia Smith, was named for her. They depended on Aunt Lou who always "seemed to be around to help when someone was sick."25

Marchbanks hired Moses W. "George" Bagley to undertake the heavy labor of stock-tending, plowing and planting, fencing fuel hauling, etc. Bagley was born in 1845 and probably began life as a slave. Oddly, Marchbanks seems not to have paid him. Years later, when she died, he submitted a claim against her estate stating that he had worked for her without remuneration for 25 years. He received $450 from the estate and the proceeds from the 1912 crop.26

In 1896, her sister Margaret's son, Burr Officer, and his son, Ted, moved to the area and homesteaded almost immediately north of their Aunt Lou's. Like Marchbanks, Burr was born a Tennessee slave.27

Lucretia Marchbanks' ranch holdings were relatively small and she did not make a concerted effort to pursue wealth. She was more inclined toward retirement than continued labor.

Her final days

Aunt Lou enjoyed her last days--she would sit on her porch and happily puff on her pipe. Occasionally she would go back to the Hills and visit her many friends in Central City and Lead. They would also visit her and sometimes their children would spend several days on the ranch. The area people also thought a lot of her and during round-ups she was well supplied with choice quarters of beef. 28

Image

Lucretia Marchbanks' health began to fail in the early 1900s and she passed away on Nov. 20, 1911, at 78 or 79 years of age.29 The funeral service, conducted by Reverend Roberts from the Methodist Church in Sundance, was held in her ranch house. He later described the scene:

"When she died I had the honor to go to Beulah and conduct services. A large crowd of friends and admirers were present to pay their last tribute of respect to one whom they loved, although her skin was black. I remember well the occasion. I preached from the text, 'She hath done what she could.' We returned her body to the earth, believing her soul had gone to the God who gave it.

Loving white hands laid to rest the good woman--Lucretia Marchbanks, the Black queen of the Hills ... When the Recording Angel opens the great Judgment Book, the name of Lucretia Marchbanks ... deserves to head the list of all the argonauts who followed the rainbow to the wild Black Hills in quest of the pot of gold."30

White hands alone did not lay her to rest. A number of Black American relatives and friends, including Marchbanks' only surviving sibling, Mattie Marshall, also attended the funeral. All the regional newspapers printed lengthy eulogies and obituaries as the Hills mourned her passing.

The legacy of Aunt Lou

Lucretia Marchbanks, ex-slave and veteran of the California gold rush, was in the wild Black Hills from June of 1876 at the height of the boomtown excitement, alongside "the restless, the ambitious, the curious ... the prospectors and miners ... the representatives of every prominent mining district of the west, as well as ‘tenderfeet’ from every state of the Union ... the buckskin clad hunter [and] the dandified gambler and the pilgrim from New England."31

In that throng were hundreds of Black Americans, among whom she was the most prominent. Lou Marchbanks had traveled all over the West and lived the now almost mythical life of the pioneers. She fulfilled the 1855 prophecy of San Francisco minister Darius Stokes who, in addressing the First State Convention of the Colored Citizens of California stated,

The white man came, and we came with him; and by the blessing of God, we shall stay with him, side by side, … should another Sutter discover another El Dorado … no sooner shall the white man’s foot be firmly planted there, than looking over his shoulder he will see the black man, like his shadow, by his side.32

Black Americans had indeed helped settle and develop all parts of the American West. Lucretia Marchbanks personally played a role in the process from antebellum days as a slave during the California Gold Rush until the early 20th Century when she continued to pioneer new roles as a single, female non-white rancher. She was not content to be a mere shadow, instead working diligently to live her own life on her own terms, to the greatest extent possible, and in so doing, lead the way for others to follow regardless of race or gender.

Editor’s Note: Editor's note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, whose support helped make the publication of this article possible.

Photos Courtesy of Western Mining History, Museum of the American West, South Dakota Historical Society, and Crook County Museum.

Endnotes, Lucretia Marchbanks: A Black Woman in The Black Hills.

Footnotes

- Black Hills Daily Times, Monday Dec. 12, 1881. A reference to Aunt Lou was included in a story about the DeSmet Mine published in the Black Hills Daily Times of Nov. 14, 1881. That statement, “Aunt Lou, mother of Father DeSmet, still reigns supreme in the mansion …” piqued the curiosity of staff on the New York Daily Stock Report and prompted the exchange. See also, Vernice White, "Lucretia Marchbanks A Former Slave," in Pioneers of Crook County, (Sundance, Wyoming: Crook County Historical Society?, 1981), p. 310, 311.

- George W. Stokes with Howard R. Driggs, Deadwood Gold: A Story of the Black Hills, (Yonkers on Hudson, New York: World Book Co., 1927), p. 75.

- Interview with Karen Glover, May 12, 1994. Glover is a Sundance-Beulah, Wyoming area local historian and former Crook County Treasurer whose family was well acquainted with their neighbor, Lucretia Marchbanks.

- Patricia Nelson Limerick examines the complexities of frontier race relations in The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West, (New York: W.W. Norton, 1987); Irma H. Klock, Black Hills Ladies: The Frail and the Fair, (Deadwood: Dakota Graphics, 1980), p. 12, 13; Sherman W. Savage, Blacks in the West, (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1976), p. 70.

- Kenneth W. Porter, "Negroes and Indians on the Texas Frontier, 1831-1876: A Study in Race and Culture," in Porter, editor, The Negro on the American Frontier, (New York: Arno Press, 1971), p. 392-393; Barbara A. Neal Ledbetter, Fort Belknap Frontier Saga: Indians, Negroes and Anglo-Americans on the Texas Frontier, (Burnet, Texas: Eakin Press, 1982), p. 114-118, 135-137. Physical evidence of Native American-Black American relations which demonstrates Indian recognition of the Black American role in white settlement, unwilling as it may have been, is found at the site of an 1860s trading post in eastern Wyoming, not far south of the Black Hills. Several slaves who labored at the Rock Ranch on the Oregon – California Trail were among the settlers besieged and attacked by Sioux and Cheyenne warriors when at least one slave was killed. This author assisted in the recovery and curation of his mutilated remains during and after archaeological excavations in 1980. See, Chapter 3, The Rock Ranch Site, in, Todd Guenther, "At Home On The Range: Black Settlement in Rural Wyoming, 1850-1950," M.A. thesis, University of Wyoming, 1988, p. 112-114; George M. Zeimans, Alan Korell, Don Housh, Dennis Eisenbarth, and Bob Curry, “The Korell-Bordeaux and Rock Ranch Protohistoric Sites: A Preliminary Report,” The Wyoming Archaeologist, 30(3-4 Fall 1987):68-92; George M. Zeimans, “The Rock Ranch Fauna: A Preliminary Analysis,” The Wyoming Archaeologist, 30(3-4 Fall 1987):93; and George W. Gill, “Human Skeletons from the Rock Ranch and Korell-Bordeaux Sites,” The Wyoming Archaeologist, 30(3-4 Fall 1987):103-107.

- Thomas E. Odell, "She Was Mother to All Folks in Early Deadwood," unidentified newspaper clipping, believed to be either the Sundance Times or Queen City Mail, n.d. (ca. 1946), in scrapbook in Crook County Public Library, Sundance, Wyoming. Odell is identified as a “Spearfish writer and Black Hills historian.” Odell’s article, based on old Black Hills Daily Times articles and interviews with gold rush survivors, seems to be the source for much of the recently published information about Marchbanks. Aaron Paragon (nephew of Lucretia Marchbanks) letter to Clerk of District Court L. Mauch, December 26, 1911 in Crook County, Wyoming probate files names nine siblings. The tenth, Crocket, is identified in a March 15, 1912 letter by another relative, Vincent Gardenshire, to the executor of the estate which is also found in Lou’s probate records.

- Quintard Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier, (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998), p. 76-81; Odell, "She Was Mother to All."

- One brother died in Leadville, Colorado in August or September of 1881, Black Hills Daily Times, August 16, 1881, September 13, 1881; Lou’s nephew, Aaron Paragon letter to Clerk of District Court L. Mauch, December 26, 1911, states that Lou's brother Finella lived somewhere in Colorado. Another brother, Finley, lived in Brother, Colorado and her sister Martha Ann (Mattie) Marshall lived in Pueblo, Colorado. At least one of sister Mirah's children, Walter Paragon, also moved west and resided in Estic, Nebraska. Sister Margaret's son, Burr Officer and his family moved to the Black Hills and lived near Lucretia; Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier, p. 104, 105.

- Odell, “She Was Mother To All.”

- Sally Zanjani, A Mine of Her Own: Women Prospectors in the American West, 1850-1950, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997); Stokes and Driggs, Deadwood Gold, p. 75, 76; John G. Bourke, On the Border With Crook, (reprinted, Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 1971), p. 384; the Black Hills Daily Times of August 8, 1881, notes that “Mrs. John Kam, of Central City [was] staking off a claim … that she thinks is a bonanza.” Her primary activity was running a boarding house and she did not evidently intend to mine the claim herself, however.

- White, "Lucretia Marchbanks: A Former Slave," p. 310-311.

- Klock, Black Hills Ladies: The Frail and the Fair, p. 12.

- Parker, Deadwood: The Golden Years, p. 74-76.

- Odell, “She Was Mother To All;” Bourke, On The Border With Crook, p. 384, 385.

- O’Dell, “She Was Mother to All;” “Central,” Black Hills Daily Times, August 15, 1879.

- Klock, Black Hills Ladies, p. 12,13; all 246 pages of Joseph R. Conlin’s excellent book, Bacon, Beans, and Gallantines: Food and Foodways on the Western Mining Frontier, (Reno & Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 1986) is entirely devoted to the discussion of food acquisition, preparation and consumption in mining camps; Parker, Deadwood: The Golden Years, p. 74, 75.

- Black Hills Daily Times, June 5, 1883.

- Black Hills Daily Times, June 12, 1883; see also, Klock, Black Hills Ladies, p. 12, 13.

- Parker, Deadwood: The Golden Years, p. 81, 141; Thomas R. Buecker, “Confrontation at Sturgis: An Episode in Civil-Military Race Relations, 1885,” South Dakota History, 14(Fall 1984):238-261.

- Odell, “She Was Mother To All.”

- Odell, “She Was Mother To All.”

- Odell, “She Was Mother To All;” Lucretia Marchbank probate files, Crook County Courthouse.

- Crook County Assessment Roll for 1887, page 53, Crook County Assessor’s Office, Sundance, Wyoming.

- Odell, “She Was Mother To All;” Karen Glover, "Rocky Ford, Crook County, Wyoming," (unpublished manuscript in possession of author, n.d.), p. 1; “Up-Gulch Items,” Black Hills Daily Times, October 18, 1885. The legal description of her property was W/E, NE/SE, and E/NW/SE/SW of Section 8, Township 52 North, Range 61 West.

- Interview with Violet Smith, whose husband is a descendant of Lou’s neighbors, one of whom, Annie Lucretia Smith, was named for the woman who helped deliver her into the world, May 12, 1994, Crook County Library; Karen Glover, personal communication, May 1994.

- Odell, “She Was Mother To All;” Marchbanks probate records.

- "Burr and Ted Officer," Pioneers of Crook County, p. 371; Karen Glover, personal communication, May 1994. The Officers’ homestead was located in Section 5, Township 52 North, Range 61 West. Crook County assessment roll, 1905, Crook County Assessor's Office, Sundance, Wyoming. See also Hills, Gold Pans & Broken Picks, p.146-147.

- Klock, Black Hills Ladies: The Frail and the Fair, p. 13.

- Lucretia Marchbanks probate files, Clerk of Court Office, Crook County Courthouse, Sundance, Wyoming. Knode's bill for services performed in March 1908 was submitted June 1, 1912. Clarenbach's bill was dated February 12, 1912 and itemized services he performed between February 1907 and November 1911. H.A. Lilly, Mgr., Sundance Pharmacy bill dated May 8, 1912.

- Quoted in Odell, "She Was Mother to All."

- Paul, Mining Frontiers of the Far West, p. 178.

- Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier, p. 134.