- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Rock Springs Massacre

The Rock Springs Massacre

Perhaps the odor of burnt things gave the men some idea of what they were about to see. Mixed with it was a sicker, sweeter smell — the smell of dead things that had started to decay.

The 600 Chinese coal miners had been traveling all day — toward San Francisco, they had been told, and safety. Then they stopped, and the sound of the boxcar doors being slid open came rumbling down the train. Outside it was after sundown, and dark, but still the men knew immediately where they were. They were right back in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory. Clambering out of the cars and onto the railroad tracks, they saw that little was left of the homes they fled in panic a week before.

Rock Springs’ Chinatown was gone. Even more horrifying, there still were bodies in what had been Chinatown’s streets. Not that many—perhaps a dozen; two dozen at the most. Some had been buried by the coal company, but these had not. Many were in pieces. These were bodies of their friends, sons, fathers, brothers and cousins, murdered by a mob of white coal miners.

“[M]angled and decomposed,” the Chinese miners reported later to a Chinese diplomat in New York, the bodies “were being eaten by dogs and hogs.”

And now the coal company, owned by the Union Pacific Railroad, expected the miners to bury their dead, put the memories of this abomination behind them and go back to work. Until new houses could be built, they would be living in the boxcars.

The trouble was a long time coming. The boxcar doors rumbled open on a night in September 1885, but there were Chinese miners in the United States at least since the California Gold Rush in 1849. Nearly all came without their families. In California, they could earn 10 times as much as they could earn in China. If they were careful, in a few years they could save a lifetime’s fortune to take back home.

California welcomed them, badly needing the work they could do. Soon Chinese men were working alongside whites at jobs from farming to cigar‑making.

When it came time to build the transcontinental railroad east from Sacramento, over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Chinese workers, though physically small, proved to be reliable, strong and very tough. They had to be. Blasting tunnels through hard rock, cutting ledges for the railroad along cliffs and mountainsides was dangerous, difficult work. Out of the 12,000 Chinese who built the Central Pacific, about 1,200 died on the job. In 1869, the Central Pacific met the Union Pacific in Utah, and the nation had a transcontinental railroad. Thousands of jobs disappeared.

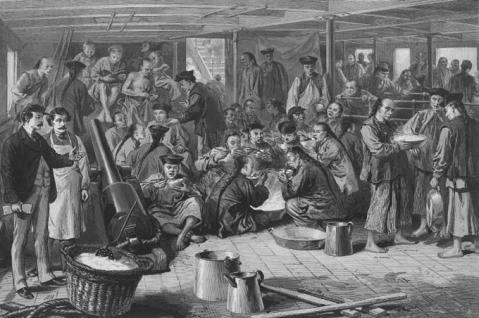

Still, the Chinese stayed. Because their families were not with them, the men did not mind living eight or nine to a room to save on rent. This kept their expenses very low. They could afford to accept jobs at a lower rate of pay. They began, in the eyes of white workers, taking jobs away from the white men.

In July 1870, white workers in San Francisco led large street demonstrations making clear the Chinese weren’t wanted—and should not consider themselves safe. In October 1871, when a fight broke out in Los Angeles between rival gangs of Chinese criminals, whites poured into the neighborhood and murdered 23 Chinese. No one was charged with the crimes.

The Chinese still kept coming to the United States. “Sojourners,” they called themselves, meaning that returning to China was always part of the plan. There was more violence—in Arizona and Nevada as well as California. In 1882, Congress finally limited the number of Chinese immigrants. But the new law was full of loopholes, and the immigration question was as open-ended and confusing as ever.

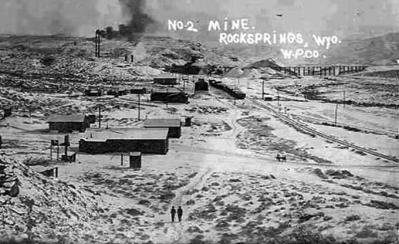

Coal was the main reason the railroad followed the route it did across southern Wyoming. The trains ran on coal from rich Union Pacific coal mines in Carbon, Wyoming, near Medicine Bow; in Rock Springs; and in Almy, near Evanston.

When the Union Pacific got in financial trouble, the railroad saved money by cutting the miners’ pay. To keep profits higher, the miners and their families were required to shop for food, clothes and tools only at the company’s stores, where prices were high. There were strikes about wage cuts, and more strikes about having to shop at the company stores.

After one such strike in 1871, the company fired the strikers and brought in Scandinavian miners ready to work for less and follow the rules. In 1875, after another strike, the company brought in additional Chinese miners ready to do the same.

It worked. Both times, federal troops came in, and the strikers lost the struggle. After the 1875 strike, the Rock Springs mines started up again with about 150 Chinese miners and only 50 whites. By 1885, there were nearly 600 Chinese and 300 white miners working the Rock Springs mines.

The whites—mostly Irish, Scandinavian, English and Welsh immigrants—lived in downtown Rock Springs. The Chinese lived in what the whites called Chinatown, to the northeast, on the other side of a bend in the railroad tracks and across Bitter Creek. There the miners lived in small wooden houses the company had built for them. Other Chinese who ran businesses—herb stores, laundries, noodle shops, social clubs—lived in shacks they built themselves.

Although they worked side by side every day, whites and Chinese spoke separate languages and lived separate lives. They knew very little about each other. This made it possible for each race to think of the other, somehow, as not entirely human.

Because the Chinese were willing to work for lower wages, everyone’s wages stayed low. This was fine with the company, but white miners resented it. They joined a new union, the Knights of Labor, growing in numbers across the nation at that time. After yet another strike in 1884, mine managers in Rock Springs were told to hire only Chinese.

In the summer of 1885, there were scattered threats against and beatings of Chinese men in Cheyenne, Laramie and Rawlins. Threatening posters turned up in the railroad towns warning the Chinese to leave Wyoming Territory or else. Company officials ignored these signs as well as direct warnings from the union.

On the morning of Sept. 2, 1885, a fight broke out between white and Chinese miners in the No. 6 mine in Rock Springs. Whites fatally wounded a Chinese miner with blows of a pick to the skull. A second Chinese was badly beaten. Finally a foreman arrived and ended the violence.

But instead of going back to work, the white miners went home and fetched guns, hatchets, knives and clubs. They gathered on the railroad tracks near the No. 6 mine, north of downtown and Chinatown. Some made an effort to calm things down, but most moved to the Knights of Labor hall, had a meeting and then went to the saloons, where miners from other mines began showing up as well. Sensing the increasing tension, the saloon owners closed their doors.

In Chinatown, it was a Chinese holiday. Many of the miners stayed home from work and were unaware of what was developing.

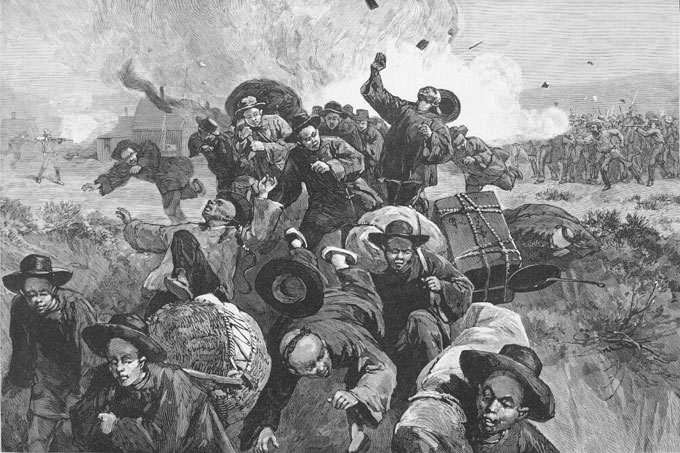

Shortly after noon, between 100 and 150 armed white men, mostly miners and railroad workers, convened again at the railroad tracks near the No. 6 mine. Many women and even children joined them. About two in the afternoon, the mob divided. Half moved toward Chinatown across a plank bridge over Bitter Creek. Others approached by the railroad bridge, leaving some behind at both bridges to prevent any nonwhites from leaving. Still others walked up the hill toward the No. 3 mine, north and on the other side of the tracks from Chinatown. Chinatown was nearly surrounded.

In the buildings at the Number 3 mine, white men shot Chinese workers, killing several. The mob moved into Chinatown from three directions, pulling some Chinese men from their homes and shooting others as they came into the street. Most fled, dashing through the creek, along the tracks or up the steep bluffs and out into the hills beyond. A few ran straight for the mob and met their deaths. White women took part in the killing, too.

The mob turned back through Chinatown, looting the shacks and houses, and then setting them on fire. More Chinese were driven out of hiding by the flames and were killed in the streets. Others burned to death in their cellars. Still others died that night out on the hills and prairies from thirst, the cold and their wounds.

With Chinatown burning, the mob confronted the company bosses who hired the Chinese and told them to leave town on the next train. They did. Over in Green River, 14 miles away, Sweetwater County Sheriff Joseph Young learned of the killing spree about an hour after it began. He rushed to Rock Springs on a special train, but no one would join him in a posse. There was nothing he could do, he said later. He and a few men protected company buildings from the fire.

In Cheyenne, Territorial Gov. Francis E. Warren learned of the murders late that afternoon. Union Pacific officials took a special, fast train all the way from company headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska, and arrived in Cheyenne about midnight. Warren joined them on the train. By daybreak on September 3, all were in Rock Springs.

Warren appeared to be the only person who knew what to do. He sent telegrams to the Army and to President Grover Cleveland in Washington asking for federal troops to restore order. And at Warren’s suggestion, the company ran a train slowly along the tracks between Rock Springs and Green River, taking stranded Chinese miners aboard and giving them food, water and blankets.

In Rock Springs, the governor met with more company officials, and then with white miners. The miners demanded that no Chinese would ever again live in Rock Springs, that no one would be arrested for the murders and burning, and they said that anyone who objected to these demands risked being hurt or killed.

To show he was unafraid, Warren left his railroad car several times during the day and made a show of walking back and forth on the depot platform. The people, now quiet and orderly, could see him clearly. Nothing happened.

Meanwhile, in Evanston, Wyoming Territory, on the railroad 100 miles west of Rock Springs, Uinta County Sheriff J.J. LeCain was nervous. Hundreds of Chinese miners lived there, too, and worked the coal mines at nearby Almy. White miners left work in Almy as well, and armed mobs were in the streets. A much larger round of killings could begin at any moment.

LeCain telegraphed Gov. Warren. With no territorial militia to command and still no definite word about federal troops, there wasn’t much Warren could do but go on to Evanston from Rock Springs. He arrived the morning of September 4. LeCain deputized 20 men who were barely managing to maintain order. On the fifth, a small detachment of troops arrived in Rock Springs. On the sixth, the striking white miners at Almy warned the Chinese that if they dared go to work, they wouldn’t leave the mines alive. Troops escorted these Chinese from their camp at Almy to the safety of the much larger Chinatown in Evanston. The company assured them their property at Almy would be safe. But as soon as the Chinese were gone, whites looted their homes.

By now, nearly all the Chinese wanted to get out of Wyoming as soon as possible. Ah Say, leader of Rock Springs’s Chinese community, asked first for railroad tickets. Company officials refused. Then, again through Ah Say, the Chinese asked for the two months of back pay the company owed them. Again, the company refused.

Two hundred fifty white citizens of Evanston next handed Governor Warren a petition asking the same thing—that the Chinese be paid off so they’d have enough money to leave. But the governor refused to do anything—a risky choice, as the situation could have exploded again at any moment. This was a matter between the company and its workers, Warren said, and none of his business.

More troops finally arrived in Rock Springs and Evanston nearly a week after the first killing. On the ninth of September, the company gathered about 600 Chinese in Evanston. Under the protection of armed guards, they were taken to the depot, loaded on boxcars and told they were headed at last to San Francisco and safety. Without their knowing, however, a special car carrying Warren and top Union Pacific officials was attached to the back of the train. About 250 soldiers were on board as well.

The train left Evanston that morning but traveled slowly east, not west, arriving in Rock Springs that evening. At the depot, an angry crowd of white miners had gathered. So the train continued a little farther, stopping just west of where Chinatown had been.

The boxcar doors opened. The Chinese realized they’d been tricked.

For several days, fearful of the jeering, catcalling white miners blocking the entrance to each mine, the Chinese would not go back to work. Again they asked for passes to California and were refused. Again they asked for their back pay and were refused. Finally, the company store refused to sell food or anything else to the Chinese who were not working and threatened to evict them from their temporary boxcar homes. About 60 refused to work and left Rock Springs any way they could.

The rest more or less surrendered. Any miner, the company declared, white or Chinese, not back at work by Monday morning, September 21, would be fired and never hired again anywhere on the Union Pacific lines. And so the miners returned to work.

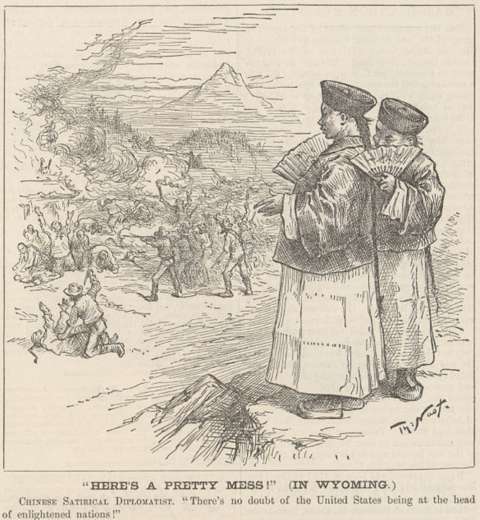

Sixteen white miners were arrested and released on bail. A grand jury was called to consider what, exactly, should be the charge. Though the killing had been done in daylight, in front of other people, no one could be found who would swear to having seen any crimes. No charges were filed.

In all, 28 Chinese were killed, 15 wounded and all 79 of the shacks and houses in Rock Springs’ Chinatown looted and burned. Chinese diplomats in New York and San Francisco drew up a list of damages totaling nearly $150,000. Congress, under pressure from the president, finally agreed to reimburse the miners for their loss. Still, the government continued to limit the number of Chinese who could come to the United States. Never having planned to stay in the first place, the Chinese gradually left Wyoming throughout the following decades.

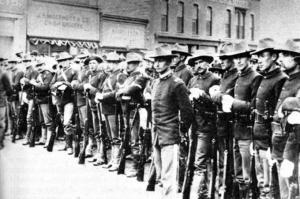

In Rock Springs, federal troops built Camp Pilot Butte between downtown Rock Springs and Chinatown to prevent further violence and stayed for 13 more years.

Thanks to Gov. Warren’s decisive courage in the first days after the riot, many more killings were avoided. But Warren also refused to help with the back-pay question and helped trick the Chinese onto the train that took them back to Rock Springs. These actions kept a big supply of Chinese miners around, making sure coal kept flowing from the mines to run the railroad and making it easier for the company to resist demands from the white miners for higher wages. And that was what the Union Pacific had wanted to do all along.

Resources

Primary sources

- “The Massacre of the Chinese,” New York Times, Sept. 5, 1885, accessed April 26, 2011, at http://www.ghostcowboy.com/node/118.

- “’Rock Springs is Killed:’ White Reaction to the Rock Springs Riot,” accessed April 26, 2011, at http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5042, a version of events published in the Rock Springs newspaper, the Independent.

- “’To This We Dissented’: The Rock Springs Riot,” accessed April 26, 2011, at http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5043/. This detailed account sent by the Chinese miners to the Chinese Consul at New York may be the best firsthand report of the September 1885 events in Rock Springs. The account includes precise physical descriptions of the corpses and of the damage to Chinatown.

- Francis E. Warren served nearly 40 years in the U.S. Senate where he quietly became one of the most powerful men in America. He died in office in 1929. He stayed a close friend of the Union Pacific throughout. His papers are among the many treasures at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Papers from his two different stints as territorial governor are at the Wyoming State Archives in Cheyenne. Finder’s guides for these are online at http://libtextml.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=wy-arrg0001_06.xml and http://libtextml.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=wy-arrg0001_10.xml.

Secondary sources

- Bowers, Carol. “‘Chinese Warren’ and the Rock Springs Massacre.” The Equality State: Essays on Intolerance and Inequality in Wyoming. Mike Mackey, editor. Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 1999, 37-62.

- Gardner, Albert Dudley. Two Paths One Destiny: A Comparison of Chinese Households and Communities in Alberta, British Columbia, Montana, and Wyoming, 1848-1910. Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, May, 2000. Excellent use of census data for a picture of 19th century Chinese communities in the West.

- Gardner, Dudley. “Wyoming History,” accessed April 26, 2011, at http://www.wwcc.cc.wy.us/wyo_hist/chinese.htm and http://www.wwcc.wy.edu/wyo_hist/ev.wyoming_and_the_chinese.htm. Background on the three Chinatowns in territorial Wyoming, and some census data. Gardner teaches history at Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 140-144.

- Nokes, R. Gregory. "'A Most Daring Outrage': Murders at Chinese Massacre Cove, 1887," Oregon Historical Quarterly, Fall 2006, accessed April 25, 2011, via JSTOR at http://www.jstor.org/pss/20615657. An account of the May 1887 slaughter of 34 Chinese gold miners by a gang of seven horse thieves on a sand bar in the Snake River on the Idaho-Oregon border.

- Storti, Craig. Incident at Bitter Creek: The Story of the Rock Springs Chinese Massacre. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1991. Storti’s book is good on the politics leading up to and following the massacre and on life in Rock Springs’s Chinatown in the 1870s and 1880s.

- Takami, David. “Chinese Americans,” accessed April 26, 2011, at http://www.historylink.org/essays/output.cfm?file_id=2060. More on the Chinese in Seattle, Wash., and the Northwest, including the forcible expulsion of Chinese from Tacoma and Seattle in 1885 and 1886.

For further reading and research

- “History of United States Immigration Laws.” Rapid Visa, accessed Sept. 19, 2019 at . A brief summary of the key provisions of immigration laws passed by the U.S. Congress from 1790 to the present.

- United States Citizenship. "Chinese Immigration and the Transcontinental Railroad." Accessed August 12, 2013 at http://www.uscitizenship.info/Chinese-immigration-and-the-Transcontinental-railroad/. Good article on the topic, with links to much more information about Chinese immigrants, their role in building the transcontinental railroad and more.

Illustrations

- The first photo shows Rock Springs’ No. 2 Mine, no date, from Wyoming Tales and Trails, with thanks.

- The illustration of the Chinese men on board ship ran in Harper's Weekly April 29, 1876, and is available from the Library of Congress.

- The Thomas Nast illustration of the massacre and his cartoon of the Chinese diplomats both ran in Vol. 29 of Harper’s Weekly in 1885, and are likewise available from the Library of Congress and the Online Archive of California. Used with thanks.

- The photo of federal troops in Rock Springs, 1885, is from Wyoming Tales and Trails.

- The photo of the street sign is by Tom Rea.