- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Law and Order In Cokeville: A Woman Mayor and P...

Law and Order in Cokeville: A Woman Mayor and Prohibition

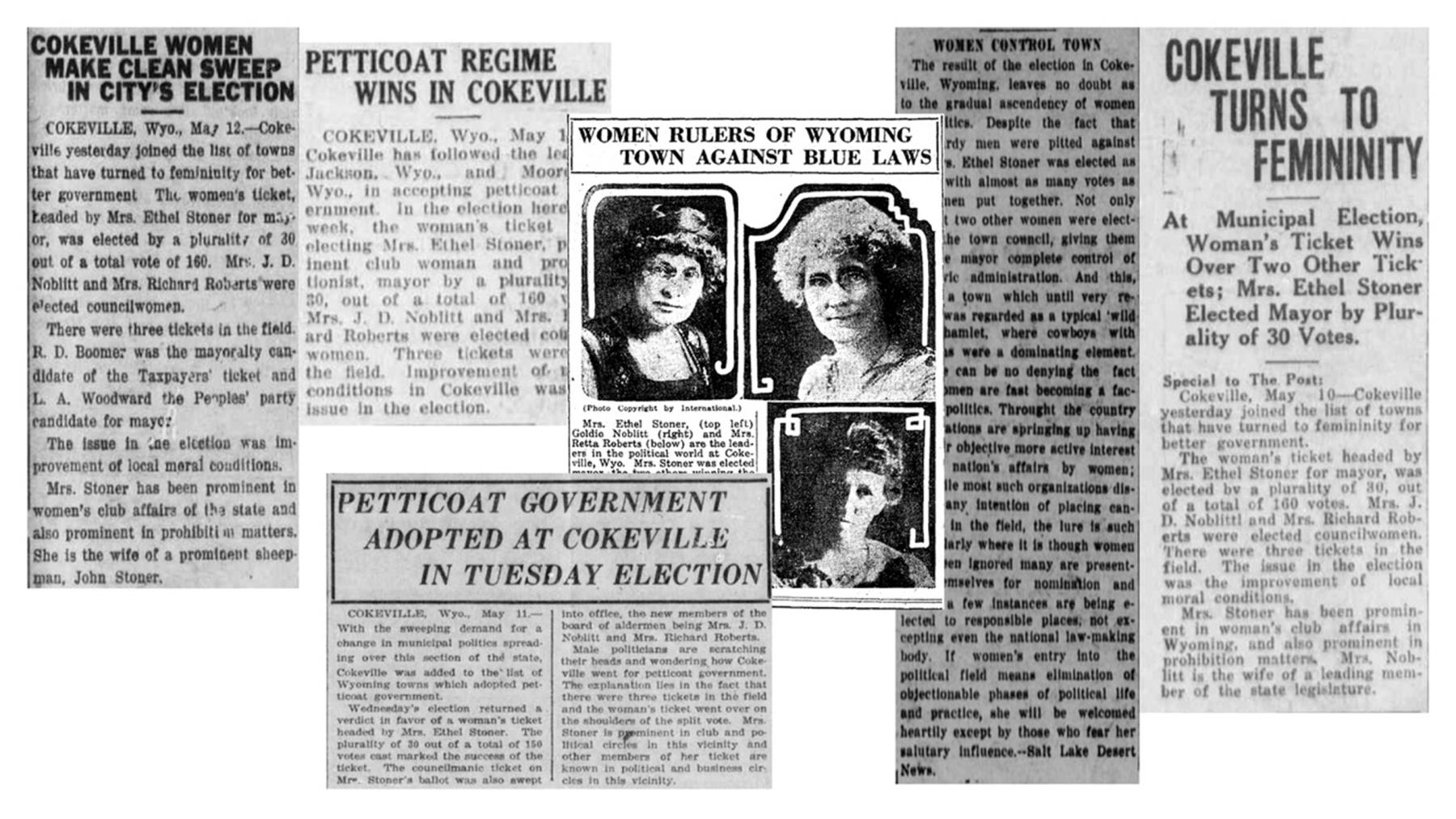

“WOMAN MAYOR IS JAILED, CHARGED WITH BEATING MAN,” read the headline. Similar versions ran on front pages across Wyoming after 1922’s Fourth of July in tiny Cokeville, Wyo., on the Idaho border. How had the town’s new mayor, elected just a month earlier on a law enforcement ticket, found herself in the middle of a street brawl?

Image

Early life

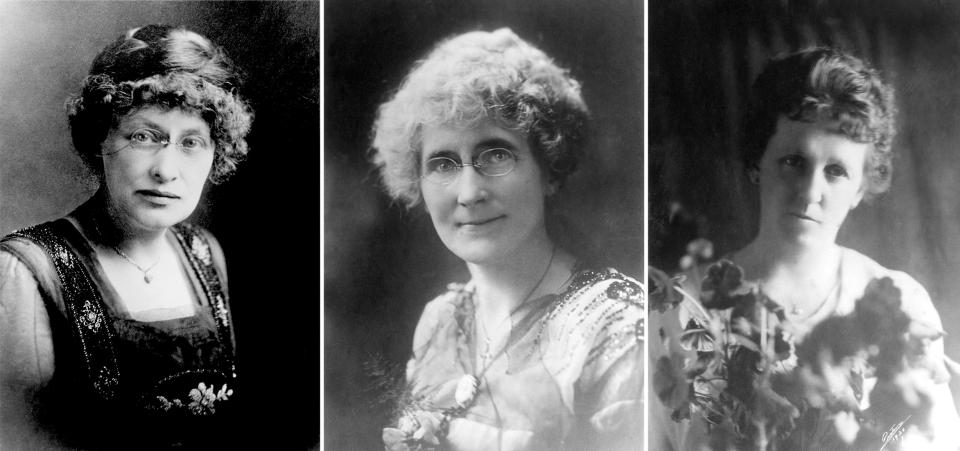

Ethel Huckvale, born Aug. 27, 1876, grew up in Bloomington, Idaho about 30 miles west of Cokeville. He parents, Jonathan and Sarah (Shurey) Huckvale, came into the area around 1861 with a party of Mormon emigrants. Ethel described herself as the “humble product of Presbyterian mission schools,” in Paris, Idaho. She went on to study in the education department of Westminster College in Salt Lake City and graduated at the age of 17.

Back home in Idaho, Ethel began teaching school and joined the successful campaign for woman suffrage, which was on the 1896 Idaho ballot and passed that year. In 1900, at the age of 24, she was hired to teach school in Cokeville and moved to Wyoming. Ethel believed that a teacher served an entire community and “must be morally efficient as well as intellectually efficient.” It wouldn’t take long for Ethel to take on the work of community moral uplift in her new home.

When Ethel arrived in Cokeville, the nondenominational Union Sunday School held the town’s only regular church service in the school building. Ethel recounted that they only employed a preacher during the summer months, so she soon found herself teaching Sunday school and Bible class, playing the organ and leading the singing. If a visiting lecturer or preacher came to town, Ethel was hostess. She even managed the upkeep of the building, acting as the school and church janitor. Recalling the experience, she later summarized, she “in short, did everything but preach the sermon and draw the salary.”

After she married John H. Stoner in January 1902, The Kemmerer Camera described her as “one of the best school teachers in the county.” John H. Stoner came to Cokeville in 1889 to work for his uncle, John W. Stoner, one of the town’s founders and a prominent merchant. Learning and working under his uncle until 1904, John H. Stoner also began raising sheep with his brother Frank in 1897. A little over a week after their first anniversary, John and Ethel welcomed a baby girl, Madaline, who tragically died 11 days later. The couple would later foster a son, Raymond A. Roberts.

For many women during this period, marriage would end her public life as a teacher and community leader. Ethel, however, continued to teach and expanded her activities. Like many women during this period, Ethel opened the door to public life through her work as a teacher and a leader in her church. She became determined to make her community a more friendly and secure place to live.

The club woman

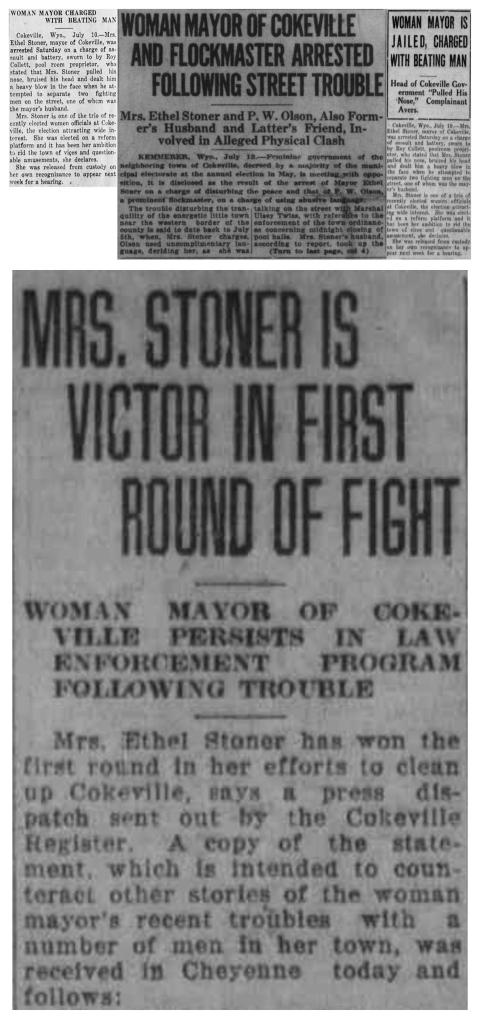

On July 5th, 1914, a brawl broke out on the streets of Cokeville. The year before Ethel had organized a Good Citizenship League, which responded to the brawl with a protest “against certain lawless conditions and corrupting influences which prevail in Cokeville today.” The protest railed against the open violation of the Anti-Gambling and Sunday Closing Law and the wild west shows given in the heart of town.

Image

The protest also demanded that public dances be placed under the discretion of “a committee who have at heart the highest moral welfare of our young people and who will at least raise the moral standard of our amusements to as high a plane as that of other towns and cities.” Nearly 60 women signed the protest, including Ethel. Ethel served three consecutive terms as president of the citizenship league. During the same period, the league stressed law enforcement and influenced elections in favor of Dry candidates who would support Prohibition.

By the summer of 1915, Ethel had taken charge of organizing a public celebration that included sporting events, music and a dance. She delivered several uplifting speeches to youth clubs and parent groups. She also coordinated the community Christmas event before wintering with her husband in Salt Lake City. Clearly, Ethel wasn’t one to just sign a protest and complain; she was the person to take charge and make things happen.

During this time, she also formed a close friendship with Goldie Noblitt, and the two women often appeared in the local newspapers traveling together with Noblitt’s daughter, Juanita. In a letter to University of Wyoming Professor Grace Raymond Hebard, Goldie described her husband, J.D. Noblitt as a well known stockgrower” with his own political ambitions. A Republican, he would go on to serve as speaker of Wyoming’s House of Representatives in 1923.

Ethel’s ambitions continued to grow as she took on leadership roles in statewide organizations like the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Wyoming Federation of Women’s Clubs (WFWC).

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Ethel naturally began organizing the countywide war effort. She served as secretary for Lincoln County’s Council of Defense and passed along recommendations for which crops to grow. She also organized Lincoln County to join the national “clean up pledge,” an effort to conserve food for the war effort. After receiving over 1,500 signatures in Lincoln County, Ethel pushed for 800 more. In her letter to the editor, she boasted:

Reports now in from over the state show that Wyoming stands sixth in the number of signatures obtained in the “clean up” campaign. We have met the challenge of the state of Florida which stands considerably further down in the list. Approximately two-thirds of the homes in Wyoming are now pledged to food conservation. The precinct chairmen are still working every where and there is a possibility that Wyoming may yet obtain the highest percentage.

The eastern magazines are praising our organization in this state. The last number of Harper’s Bazar has an article by Ida Tarbell in which she holds up the organization of our woman’s department as a model for the other states.

With national recognition of her successful leadership, Ethel’s war efforts went statewide in 1918. In her role as the WFWC chairman of the Industrial and Social Conditions Committee, Ethel pushed for the women of Wyoming to increase their Americanization efforts for new and naturalized citizens.

“Self-preservation, as well as the golden rule, now bids us make them feel at home in our land, now bids us neighbor them and patiently and sympathetically lead them to a better understanding of our government and its privileges and obligations, for we must have a united people behind the firing line.” She also warned that the war necessitated an increased alertness in safeguarding labor rights of women and children and ensuring that labor laws remained enforced.

Prohibition: Wets vs. Drys

In the midst of World War I, in December 1917, both houses of Congress passed the 18th Amendment, which then began the state-by-state ratification process. The Amendment prohibited the production, transport and sale of alcohol and would take effect one year after ratification. Thirty-six states were needed to ratify it before it became part of the constitution. Wyoming voters saw Prohibition on their November 1918 ballots.

Ethel spoke passionately about the need for Wyoming to ratify the amendment. In an address at the 1918 Annual Convention of WFWC, she spoke of the “wanton waste of man power” as men “stagger in and out of our saloons” and “jostle against” women in the streets, all while neglecting their flocks, farms and mines.

She pleaded with the women and encouraged their public engagement. “If the lives of our children were endangered by fire or flood or by wild beast, would we be too busy with our household duties to seek to protect them?” She depicted the effects of alcohol as a “worse fate than death” which “take[s] our beautiful boys and crush[es] out of them all that is pure and manly and noble and true.”

Then she ridiculed the economic argument against her position: “What are we afraid of? Afraid we might offend the man who sells this poison to our loved ones? Afraid we might lose the revenue he pays us for the privilege of ruining our boys?” With her final plea for the children, she encouraged the women to “save the boys” by voting in favor of Prohibition. Ethel wasn’t the only Wyomingite campaigning for Prohibition, with other prominent men and women across the state encouraging everyone to “vote Dry.”

When the Wyoming Legislature convened in January 1919, it ratified the 18th Amendment. On the same day, the amendment was also ratified in North Carolina, Utah, Nebraska and Missouri. Despite the votes all being held on the same day, Nebraska’s vote was the last needed for ratification, making Missouri and Wyoming the first states to ratify after the amendment passed in the required three-fourths of the states.

As Prohibition took effect in 1920, bootleggers still trafficked alcohol in and out of Cokeville, and the public drunkenness and crime that came with it continued. The local product, known as the “Kemmerer Moon,” named for nearby Kemmerer, Wyo., had a reputation for being “relatively safe” and was shipped out of Wyoming to Chicago and the West Coast. Ethel quickly became disgusted at the flagrant disregard for the 18th Amendment. Leading the fight for enforcement, she organized the Law Enforcement League. Her opponents ridiculed the league as the “Uplifting Branch,” and openly mocked the women’s efforts.

Despite the ridicule at home, Ethel’s work for prohibition and community uplift continued to be honored. Gov. Robert Carey appointed Ethel to an eight-person committee representing Wyoming at the 15th International Congress Against Alcoholism held in Washington, D.C. inSeptember 1920. Ethel couldn’t attend, however, because she was serving as a delegate to the International Council of Women’s convention in Norway at the same time. Afterward, she toured Europe with a group of women representing America before returning home to Cokeville in October.

Image

Mayor of Cokeville

In 1922, Ethel decided to challenge the Wets’ political power and began her campaign for mayor with Goldie Noblitt and Retta Roberts on her ticket for city council. She explained, “For over 20 years I have been the arch enemy in Cokeville for all that the liquor interest stood for and they would as soon have seen the de’il elected as I.” The Wets became “frantic” to defeat Ethel but couldn’t organize their efforts behind one ticket. With a split Wet vote, the three women won their election in May; Stoner won with plurality of just 30 votes out of 160 cast, according to press reports. Her mayorship lasted one year, beginning on June 4th, 1922, and she appointed Essie Dale as town clerk.

In her campaign for mayor, Ethel promised not to push for any new laws, only to enforce the laws already on the books. In a later speech, she recounted that she “soon found that enforcing the laws in western Wyo. is easier said than done.” Her hands were tied by county and state laws when it came to the search for illicit liquor, by her budget when it came to hiring undercover men, and by governmental delays when it came to bringing in federal or state agents. Though she received many promises from county, state and federal agencies, not a single arrest for bootlegging in Cokeville was made while she was in office.

A Public Brawl

The backlash against Ethel’s election resulted in more flagrant abuses of the laws she intended to enforce. She later recalled that the local leaders of the wet party accepted her mayorship in “the same spirit some unruly country boys might receive the new school ma’m pledge to keep order. They determined they would have none of this petticoat rule and they acted up accordingly, just like a lot of unruly boys.”

A month into her term, while Ethel was still figuring out how she would enforce Prohibition, the town of Cokeville held its Fourth of July celebrations. During the festivities Pete Olson, “the boss Murphy of the town, and leader of the Wets,” began to drunkenly harass Mayor Stoner in front of a crowd of his followers. (“Boss Murphy” referred to a well-known New York political kingmaker in the Democratic party, Charles F. Murphy, who, though he never held elected office, still held considerable power and influence over elections.) Olson had apparently made a habit of publicly insulting Ethel and on this night in particular, her husband John had enough. John seized Olson by the shoulders and demanded an explanation for the insults against his wife.

Ethel described what happened next in a letter to University of Wyoming Professor Hebard: “At this a drunken bootlegger sprang upon my husband's back and attempted to choke him to death. He—the bootlegger, is a cripple with only one leg, but a big man and wonderfully strong in his arms and it took the combined strength of three big men some time to tear his hands from my husband's throat, and fearing that he would be choked to death before my very eyes, I too tried to pull him off my husband's throat.”

After rescuing her husband from the bootlegger’s chokehold, Ethel determined to have Pete Olson arrested for disturbing the peace. He retaliated by having the bootlegger press charges against Ethel for assault and battery. Ethel was arrested and put in the Cokeville jail. Though she was quickly released, the story spread like wildfire across the state. Olson’s friends gave the press a story that described Ethel attacking Roy Collett, a disabled man and poolroom proprietor, by “pulling on his nose, bruising his head, and dealing him a heavy blow to the face” when he attempted to break up a street fight between Ethel’s husband and another man.

When their day in court came nearly two weeks later, Ethel prevailed. Olson admitted his guilt to the charges and paid the court costs, afterward having Collett withdraw his charge against Ethel. The Wyoming State Tribune declared, “Mrs. Stoner Victor in First Round of Fight” and that her program of law enforcement had won its first battle in the face of attempted intimidation.

In fact, Ethel had discovered the means by which she could enforce Prohibition and other laws. She recounted to the WFWC, “I rattled my sword continually, made many arrests for drunkenness and disorder, levied heavy fines and kept the bootleggers so scared up all the time that much of the joy was taken out of life for them.” She ran professional gamblers out of town, limited the pool halls to two, strictly enforced a midnight closing and kept minors from entering. “This all had much to do with bringing about a better order of things and in lessening the consumption of moonshine, but it did not destroy the traffic,” she wrote.

By March 1923, with only three months left in her term, Ethel shared her success with Hebard: “We seem to be getting Cokeville tamed down into quite an orderly little town. … The Wets think we are certainly “hard boiled” and they are living for the day when they will be delivered from petticoat rule.” Their wait wouldn’t be long as Ethel determined not to run for office again because she planned to spend the winter in Salt Lake City. Unopposed, the Wet Party still ran a smear campaign against Ethel during the election. Voter turnout dropped by nearly 50 percent in the municipal election, and Ethel believed many who voted still would have voted for her had she run again. Despite the victory of the Wets, with Noblitt and Roberts still on the council, Ethel believed that her work would not be undone. “[P]eople here will not tolerate a return to wide open conditions.”

Ethel accomplished more than cutting down on crime and public disorder while in office; she took on long-neglected projects. Under her leadership, Cokeville increased its water supply by cleaning up pollution, clearing away a bog blocking one of the springs, installing new pipes and opening a new spring. She enlarged the town cemetery and ensured the town held titles to all of the land. She improved the local campground and led cleanup efforts from city streets to the windows of city hall. She also established the Cokeville Library and ensured that it had proper funding before leaving office June 4, 1923.

After Public Service

After serving as mayor of Cokeville, Ethel spent some time in Los Angeles. She attended club meetings, took a class on public speaking and shadowed social workers in the courts and clinics. She commented to Hebard, “The club women here seem to be informing themselves upon all public questions but do not seem to be undertaking any active reform work of any kind.”

Ethel never served in public office again. But she would continue to take on leadership roles in local and statewide organizations. When Hebard asked her what she would do after leaving office she replied, “I have no definite plans yet, but I shall not be idle, and I do have visions of larger fields of usefulness somewhere, sometime. I believe the hope of the world is in its women and these must be aroused to a sense of their responsibilities. I am hoping that somewhere I may have a small part in this work.”

Author’s note: Special thanks to Angela Thompson and the Cokeville Branch Library for help in finding more sources on Cokeville and Ethel Stoner.

Editors’ note: WyoHistory.org would like to thank the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support that in part made this article possible.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Hebard and Stoner Correspondence 1923-1924. Box 45, Folder 30, Grace Raymond Hebard Papers, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo. (Hereafter AHC)

- Noblitt, Goldie. Letter to Grace Raymond Hebard, May 23, 1922. Box 28, Folder 11, Grace Raymond Hebard Papers, AHC.

- Stoner, Ethel. Address to the Wyoming Federation of Women’s Clubs, 1923. Box 45, Folder 30, Grace Raymond Hebard Papers, AHC.

- Stoner, Ethel. “Historical Sketch of Cokeville, 1923.” WPA Sub 266, WPA Federal Writers Project Files, Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- Whitney, Marion P. “The International Council of Women: Sixth Quinquennial Meeting.” Vassar Quarterly 6, no. 1. Nov. 1, 1920, accessed Jan. 29, 2023 at https://newspaperarchives.vassar.edu/?a=d&d=vq19201101-01.2.10&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN--------.

- Articles accessed from November 2022 – January 2023, from the Wyoming Newspaper Project at http://wyonewspapers.org/:

- The Kemmerer Camera 4, no. 39, Feb. 8, 1902

- “A Protest.” The Cokeville Register 4, no. 9, Aug. 8, 1914

- The Cokeville Register 5, no. 20, Oct. 23, 1915

- The Cokeville Register 5, no. 21, Oct. 30, 1915

- The Cokeville Register 7, no. 17, Sept. 22, 1917

- Star Valley Independent 14, no. 7, Sept. 28, 1917

- “Working on the Food Pledge.” The Cokeville Register 7, no. 21, Oct. 18, 1917

- The Kemmerer Camera 20, no. 31, Dec. 5, 1917

- The Kemmerer Republican 5, no. 37, May 3, 1918

- The Cokeville Register 8, no. 18, Oct. 26, 1918

- “Mrs. Stoner’s Remarks.” Star Valley Independent 15, no. 6, Nov. 1, 1918

- The Laramie Republican 30, no. 74, Nov. 5, 1919

- Cheyenne State Leader 57, no. 186, Sept. 4, 1920

- The Casper Daily Tribune 6, no. 182, May 11, 1922

- The Sheridan Post 35, no. 318, May 11, 1922

- The Sheridan Enterprise 14, no. 226, May 13, 1922

- The Cody Enterprise 23, no. 41, May 17, 1922

- The Wyoming Press 26, no. 42, June 17, 1922

- Wyoming State Tribune 28, no. 176, June 25, 1922

- The Sheridan Post 36, no. 53, July 11, 1922

- The Daily Boomerang 41, no. 165, July 13, 1922

- Wyoming State Tribune 28, no. 194, July 13, 1922

- Greybull Standard 20, no. 32, July 14, 1922

- The Daily Boomerang 41, no. 168, July 17, 1922

- Wyoming State Tribune 28, no. 198, July 17, 1922

- Dayton Daily News 36, no. 274, May 22, 1922. Accessed via subscription to Newspapers.com by Ancestry on Jan. 19, 2023.

Secondary Sources

- Bartlett, Ichabod S. History of Wyoming, Vol. 3, S.J. Clark Publishing Company, 1918.

- Beach, Cora M., Women of Wyoming. Cheyenne, Wyo., 1927, pp. 485–487.

- Clark, Eva N. Cokeville: Biographies of Her Colonizers, 1870-1900. Self-published 2011, 226-232.

- Dayton, Donetta. “Early Pioneers: Mrs. Ethel Stoner.” WPA Bio 2408, WPA Federal Writers Project Files, Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- Lloyd, Errol Jack. “The History of Cokeville.” University of Utah, 1970. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations, 7509, accessed Feb. 1, 2023, from https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7509.

- May, Kate Torgovnick. “We Can’t Do Much Worse Than the Men.” The Atlantic, Oct. 9, 2016, accessed November 2022 at https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/10/we-cant-do-much-worse-than-the-men/503432/.

- Nofil, Brianna. “In the 1920s, the Now-Forgotten Flood of ‘Girl Mayors’ Became the Face of Feminisim.” Atlas Obscura, July 6, 2016, accessed Nov. 9, 2022, from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/in-the-1920s-the-nowforgotten-flood-of-girl-mayors-became-the-face-of-feminism.

- Rankin, Charles E. “Teaching: Opportunity and Limitation for Wyoming Women.” Western Historical Quarterly 21, no. 2 (May 1990): 147-70.

- Rea, Tom. “Booze, Cops, and Bootleggers: Enforcing Prohibition in Central Wyoming.” WyoHistory.org, July 16, 2016, accessed Jan. 16, 2023: /encyclopedia/booze-cops-and-bootleggers-enforcing-prohibition-central-wyoming

- _______. “Wyoming’s First Woman Mayor.” WyoHistory.org, Oct. 23, 2019, accessed Nov. 9, 2022 from, /encyclopedia/wyomings-first-woman-mayor

- Van Nuys, Frank. “Grace Raymond Hebard and Americanization in Wyoming.” Wyoming Almanac, accessed Feb. 16, 2023 at https://wyomingalmanac.com/?p=923. First published in Phil Roberts, ed., Readings in Wyoming History: Issues in the History of the Equality State, 4th edition. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Skyline Press, 2004, 147-165.

Illustrations

- The photos are all from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The newspaper headlines, assembled into composites by the author, are from images of newspapers listed in the bibliography and available via the Wyoming Newspaper Project. Used with thanks.