- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Cokeville Elementary School Bombing

Cokeville Elementary School Bombing

May 16, 1986, will never be forgotten by the residents of Cokeville, Wyo. On that Friday afternoon in their quiet, rural town, a deranged couple entered the community’s elementary school, took those inside hostage and detonated a bomb in a first grade classroom.

At that time, about 500 people lived in Cokeville, and there were slightly more than 100 students attending the elementary school. Located in Lincoln County and nestled between the towns of Star Valley and Kemmerer on the Wyoming-Idaho border, Cokeville, many residents believed, was a safe place to rear children.

“[T]rust is big here … youngsters grow up knowing they can turn to many other members of the community with confidence,” write Hartt and Judene Wixom in Trial by Terror: The Child-hostage Crisis in Cokeville, Wyoming. The first chapter is titled “A Town of Trust.”

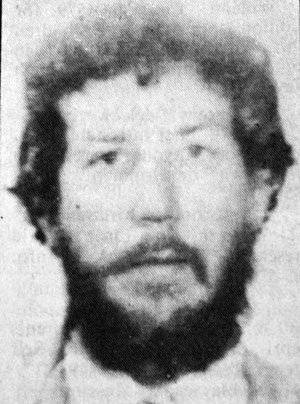

Thus, when David and Doris Young entered the town’s only elementary school with an arsenal of weapons and a gasoline bomb in a grocery cart, no one saw it coming. David Young’s journals and writings reveal that he was a troubled man who spent many years grappling with deep philosophical questions–about man’s existence, the afterlife and spirituality.

Educated at Chadron State College in Nebraska, he had earned a degree in criminal justice, and was hired as Cokeville’s town marshal in the 1970s. He was dismissed, however, from this position shortly after his six-month probationary period. Young met his second wife, Doris Waters, while in Cokeville. She was a divorcée who earned money working as a waitress and singer in a local bar. Shortly after their wedding, David and Doris left Cokeville and headed to Tucson, Ariz.

During their time in Tucson, according to Doris’ daughter Bernie Petersen, David became increasingly reclusive, focusing on his philosophical readings and writings. While he was writing his philosophy, Zero Equals Infinity, Doris took part-time jobs including housekeeping and waitressing to support their meager lifestyle. They lived in a mobile home with Princess, David’s youngest daughter from his first marriage. He was the father of two, but was estranged from his elder daughter.

It was in their Tucson home that David came up with what he considered “the Biggie,” a plan to get rich quick and create a “Brave New World.” This plan involved David’s longtime friends, Gerald Deppe and Doyle Mendenhall, who believed by investing in David’s scheme they would get rich. But David refused to reveal his plans entirely until moments before they unfolded.

David’s friends did not know that “the Biggie” was a plan to take over Cokeville Elementary School, hold each of the children hostage for $2 million dollars apiece and then detonate the bomb, transporting the money and children to his “Brave New World,” where he would be God. While David and Doris Young were not involved in an organized religion, both were deeply spiritual. They believed in reincarnation, which probably led, in part, to the creation of David’s “Brave New World” idea. David’s writings reveal that he hoped life would be better for him and Cokeville’s children in this imaginary place.

When Deppe and Mendenhall finally got wind of his plans moments before the hostage crisis unfolded, they refused to participate. David, who dared not risk their reporting him to the authorities, responded by holding them at gunpoint. He instructed Doris and Princess, by now a young adult, to handcuff them inside his van.

David, Doris and Princess proceeded to the elementary school and entered the building shortly after 1 p.m. that Friday. David had the makeshift bomb attached to his body and housed inside a grocery cart, while Doris and Princess carried an arsenal of rifles, handguns and ammunition, as well as the Zero Equals Infinity handouts.

But shortly after entering the school, Princess decided to rebel. She fled the building and drove the Youngs’ van—with Deppe and Mendenhall still inside—to the town hall, where she reported her father’s plan. Because they refused to participate, Princess, Deppe, and Mendenhall were never charged in relation to this crime.

In the meantime, David and Doris Young gathered children, teachers, staff and visitors in the elementary school into one central location. They attempted to crowd 154 people into one of the two first grade classrooms, a room with a total capacity of 30 students and a teacher. David set himself near the center of the room with the grocery cart bomb nearby, as Doris went from room to room rounding up people.

According to survivor accounts, Doris enticed many into the first grade room by announcing that their presence was required for a school assembly. Of course, most children were elated by the prospects of an assembly. Upon entering the classroom, children saw an arsenal of weapons, a grocery cart and an unfamiliar man—David Young. Some of them believed the assembly was about weapons; others began realizing something was seriously wrong.

Once all the hostages were contained in the first grade classroom, David Young informed them that they were leading a revolution and distributed copies of his philosophy Zero Equals Infinity to everyone present. Just before implementing “the Biggie,” David Young had also sent a copy of the document to President Ronald Reagan, the president of Chadron State College and numerous media outlets. Cokeville Elementary School teachers and staff tried to keep kindergarteners through sixth graders calm and entertained. In the tiny classroom, they watched movies, played games, prayed. And, then, shortly after 4 p.m., the bomb exploded.

Witnesses later testified that just before the explosion David Young had connected the explosive to his wife. Then he went to the restroom, which was attached to the classroom. Doris accidently triggered the bomb by motioning to her hostages with her arms. The explosion engulfed her in flames and burned many nearby children.

Chaos ensued. David emerged from the bathroom to find his wife in excruciating pain. He shot and killed her. Students, teachers, staff and visitors frantically exited the building, with teachers helping many of the children escape through the windows. David saw John Miller, the music teacher, trying to escape and shot him in the back. David returned to the restroom and killed himself, ending the hostage crisis. The only two fatalities were David and Doris Young. Everyone else survived, including the injured John Miller.

Reporters from all the regional news outlets were on the scene by the time of the explosion or shortly thereafter. In addition, national reporters began arriving within hours of the explosion. Students, teachers, visitors, staff who survived the ordeal and bystanders began recounting their memories of this event as it was still unfolding.

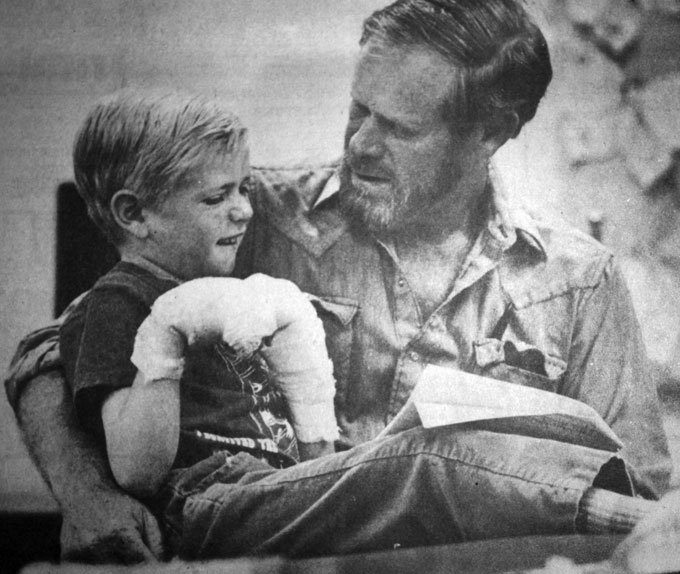

Following the explosion, 79 children were taken to area hospitals, most of which were located more than an hour’s drive from Cokeville, for treatment for burns and smoke inhalation. Survivors shared their stories with each other, investigators, family members, and hospital personnel. In the days and weeks immediately after this event, most accounts focused on the horrors of the day.

As time progressed, however, a different story emerged in this highly religious and largely Mormon community. It became a story of a miracle rather than a tragedy. Oral histories, memoirs and drawings began to reveal a narrative of fortune rather than misfortune. Survivors began to tell their stories through a spiritual lens. They increasingly spoke about their memories in public with professional psychologists, church officials and community counselors.

Many recalled praying silently, forming prayer circles and seeing angels during the crisis. This narrative was perpetuated in many publications and productions. For instance, The Cokeville Miracle Foundation’s 2005 book Witness to Miracles: Remembering the Cokeville Elementary School Bombing and the Wyoming State Archives oral history project called “Survivor is My Name” both focused on the reconstructing of this narrative as a miracle instead of a tragedy.

Kameron Wixom, son of Hartt and Judene Wixom, writes a “childlike faith saved us.” In his contribution to the Witness to Miracles book, Kameron writes: “I didn’t have to see angels, hear them, or even think that their presence might be required that day. I did not have to imagine how God would move … that day when I said my little prayer just hours before, I simply knew he would. He did deliver our salvation that day. That much I know. I’m living proof.”

Resources

Primary Sources

- “A Projectile Killed Doris Young, Not Bomb Blast, Police in Cokeville Say.” Deseret News, May 24, 1986, 11. Accessed May 17, 2013 at http://news.google.com/newspapers/p/deseret_news?id=nz1TAAAAIBAJ&sjid=BYQDAAAAIBAJ&pg=4165,3587249&dq=cokeville+bombing&hl=en.

- Castaneda, Sue and Mark Junge. “Survivor is my Name: Voices of the Cokeville Elementary School Bombing.” Produced by Wyoming State Archives for Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources, the package includes interviews with 14 people about the events of May 16, 1986. Accessed May 28, 2013 at http://archive.org/details/SurvivorIsMyName-VoicesOfTheCokevilleElementarySchoolBombing.

- “Cokeville Bombing.” Undated scrapbook. Cokeville Public Library.

- “Cokeville Children Held Hostage by Bomber.” News Examiner, May 22, 1986.

- “Cokeville Elementary School Bombing: 25-Years Later.” Accessed May 17, 2013, at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udNB_xdPiYE.

- Cokeville Miracle Foundation. Witness to Miracles: Remembering the Cokeville Elementary School Bombing. Greybull, Wyo.: Pronghorn Press, 2006.

- Fagg, Ellen. “Cokeville Trying to Rebuild A Normal and Secure Life.” Deseret News, May 20, 1986, 9. Accessed May 17, 2013, at http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=mz1TAAAAIBAJ&sjid=BYQDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6656,2193766&dq=cokeville+trying+to+rebuild&hl=en.

- Green River Star, May 20, 1986.

- Kemmerer Gazette, May 22, 1986.

- Lota, Louinn. “Healing will come Slowly From Within a Wounded Cokeville. Deseret News, May 25, 1986, 10. Accessed May 17, 2013, at http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=oD1TAAAAIBAJ&sjid=BYQDAAAAIBAJ&dq=cokeville&pg=7027%2C3851642.

- Peterson, Carol. Interview by Mark Junge. Audio/Video Recording. Sept. 21, 2010. Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources, Cheyenne. Accessed May 17, 2013, at

- http://wyospcr.state.wy.us/MultiMedia/Display.aspx?ID=86&icon=1.

- Repanshek, Kurt J. “Wyoming Town Still Healing a Year After School Bombing.” Lewiston Daily Sun, May 29, 1987. Accessed June 10, 2013, at

- http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1928&dat=19870529&id=-AogAAAAIBAJ&sjid=c2UFAAAAIBAJ&pg=1067,6238243.

- Rock Springs Daily Rocket Miner, May 17-May 23, 1986.

- “Schoolhouse Blast Still Felt a Year Later.” Milwaukee Journal, May 21, 1987, 90. http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19870521&id=w4sfAAAAIBAJ&sjid=zH3EAAAAIBAJ&pg=4596,6209063.

- Star Valley Independent, May 22-June 19, 1986.

- “Survivor is My Name: Cokeville Elementary School Bombing–1986 News Report Audio.” Audio Recording. Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources, Cheyenne. Accessed May 17, 2013, at http://wyospcr.state.wy.us/MultiMedia/Display.aspx?ID=86&icon=1.

- Wixom, Hartt and Judene Wixom. Trial by Terror: The Child-Hostage Crisis in Cokeville, Wyoming. Bountiful, Utah: Horizon Publishers, 1987.

- ________. When Angels Intervene: To Save the Children. Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Incorporated, 1994.

- “Wyoming Horror: A Fiery Schoolhouse Bomb.” Time 127, no. 21:24 (1986).

Secondary Sources

- “A 1986 Hostage Event at a Cokeville, Wyoming Elementary School.” Unsolved Mysteries, Season 9, Episode 43. 1997.

- Jarvik, Elaine. “Cokeville Recollects ‘Miracle’ of 1986: Hostage Survivors, Town Residents Compile Book.” Deseret News (May 15, 2006). https://www.deseret.com/2006/5/15/19953524/cokeville-recollects-miracle-of-1986.

- Matray, Margaret. “25th Anniversary of Wyoming School Attack.” Denver Post.com. http://www.denverpost.com/news/ci_18072820.

- ________. “The Power of Faith: 25 Years After School Bombing, Town Remembers Story of Survival.” Casper Star Tribune (May 15, 2011). http://trib.com/news/state-and-regional/article%E2%80%943077bf4a-a45e-5dad-ae3a-a99aa8fcf3aa.html.

- Mitchell, Ruth Ann. “10 Years Later, Cokeville Just Says: Let Us Be.” Deseret News (May 15, 1996). http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=336&dat=19960515&id=Ke5LAAAAIBAJ&sjid=fuwDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5227,9406392.

- Pierce, Scott D. “‘Save the Children’ is Shallow, Exploitative: Focus is on Wacko Bomber Instead of 167 Cokeville Students and Teachers.” Deseret News (April 4, 1994). http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=336&dat=19940404&id=GoQwAAAAIBAJ&sjid=iuwDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2778,1992787.

- To Save The Children. DVD. Directed by Steven Hillard Stern. N.p.: Artisan, 2003, 92 min.

- Troone, Trent. “Cokeville Miracle Marking 25 Years.” Deseret News (May 11, 2011). http://www.deseretnews.com/article/705372484/Cokeville-miracle-marking-25-years.html.

- “Unexplained Mysteries: Angel Files.” Season 1, Episode 20. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qe_ZX4Qbsi4.

Illustrations

- The black and white photos are from the Casper Star-Tribune collection at the Casper College Western History Center. The color photo of the Cokeville School is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with thanks.