- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Great Cheyenne Flood of 1985: A Devastating...

The Great Cheyenne Flood of 1985: A Devastating Storm That Changed Wyoming’s Capitol

On the evening of August 1, 1985, the city of Cheyenne experienced one of the most catastrophic natural disasters in Wyoming’s recorded history. What began as typical summer storm clouds gathering in the western sky would transform into a deadly deluge that claimed twelve lives, injured seventy people, and caused more than $61 million in damage—equivalent to approximately $145 million in today’s dollars.1

The Storm Unfolds

The disaster began around 6:00 p.m. when a supercell thunderstorm became locked in place over Cheyenne by the jet stream.2 Unlike the brief afternoon showers common to summer evenings in southeastern Wyoming, this storm system remained stationary and unleashed its full fury on the unsuspecting city below. Weather forecasters described the event as an “upslope system” that caused four to six thunderstorms to develop over the western edge of the city, creating what one National Weather Service forecaster called a “once in 500 years” storm.3

Over the course of just three hours, the storm dropped an unprecedented amount of precipitation on Cheyenne. The most intense period occurred between 8:00 and 9:00 p.m., when 3.51 inches of rain fell in just one hour.4 The National Weather Service Forecast Office recorded an official measurement of 6.06 inches of rainfall, though some areas of the city received up to 7.87 inches. This broke the previous rainfall record for Cheyenne that had stood since 1896, when 1.7 inches fell in three hours on July 15. The 6.06-inch total also broke the previous state record of 5.5 inches set at Dull Center in Converse County on May 31, 1927.5

The rainfall was accompanied by other severe weather phenomena that compounded the disaster. Hailstones measuring up to two inches in diameter pummeled the city, accumulating in nearly foot-tall piles before being swept by powerful winds and rushing water into drifts reaching three to six feet in height. Some witnesses reported seeing hail piled up to 10 feet deep in various sectors of the city. Thunderstorm winds reached 70 mph, and the storm system spawned several funnel clouds and at least two short-lived tornadoes. Ironically, while tornado warnings were issued and sirens sounded throughout the city, the tornadoes caused no apparent damage—it was the flooding that proved catastrophic.6

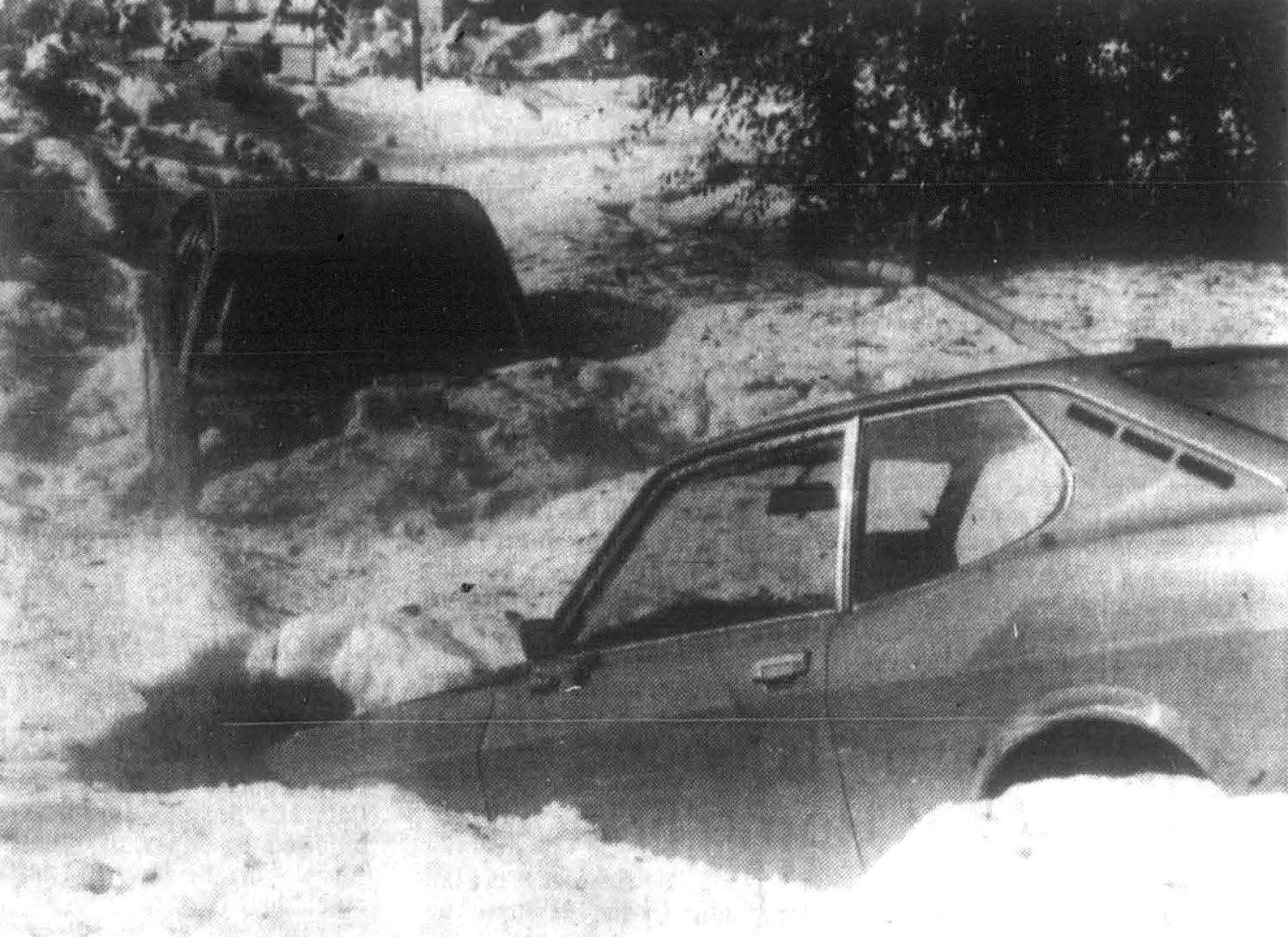

Image

Image

The Flood’s Immediate Impact

As the massive amounts of rain overwhelmed Cheyenne’s drainage systems, Crow Creek and Dry Creek were transformed from modest waterways into raging torrents. The accumulated hail played a crucial role in the disaster by clogging storm drains throughout the city, preventing normal water flow and contributing to the rapid backup that would prove so deadly.7

The fast-rising floodwaters inundated downtown Cheyenne and low-lying residential areas from Dell Range Boulevard to Holliday Park.8 Water reached depths of up to 5 feet at some intersections, and the Civic Center’s sunken parking lot was transformed into what witnesses described as a “swimming pool,” with cars stacked on top of each other by the force of the current.9 Homes and businesses were flooded as basement windows gave way under the pressure of the surging water. Many residents who had initially sought shelter in their basements when tornado sirens began sounding found themselves trapped by the sudden influx of floodwater.10

The downtown municipal block, including the Municipal Building, Civic Center, and Police Department, lost power and required emergency generators.11 Water from a parking structure seeped into the lower levels of both the Herschler Building and the Capitol. The force of water rushing down Dry Creek knocked out the underpinnings at the Sheridan Court Apartments in the Buffalo Ridge Estates neighborhood, and the nearby intersection of Sheridan and Windmill Road was left impassable for some time due to undercuts from the rushing water.12 This infrastructure damage would set the stage for massive cleanup and reconstruction efforts in the days and months to come.

The Human Toll

The human cost of the flood was devastating, with twelve lives lost and seventy people injured. Most fatalities occurred when victims were swept away in their vehicles while attempting to cross flooded streets, particularly along Dry Creek.13

Among the victims was Laramie County Sheriff’s Deputy Robert Van Alyne, Jr., whose heroic actions exemplified the courage displayed by many that night. According to the official Sheriff’s Department investigative report, Van Alyne had gone door-to-door asking residents if they needed help before obtaining ropes from a local scoutmaster. Around 10:15 p.m., he was working hand-over-hand on a rope tied between two poles, attempting to rescue 6-year-old Kristi Hernandez from a stranded vehicle at Windmill and Dell Range Boulevard. After reaching the car and putting the child on his back, he was swept away by a large swell of water as he tried to return to safety. Both drowned.14 More than 400 mourners, including at least 100 uniformed law enforcement officers, filled Cheyenne’s First Presbyterian Church on August 5 to honor Van Alyne, who was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.15

The complete list of those who perished includes Joelie Pando, 16 (daughter of Cheyenne police detective Leo Pando); Robert Van Alyne, Jr., 33; Kristi Hernandez, 6; Kumi Mostert, 7; Rose Marie Scott, 17; James R. Jenkins, 18; Alice Paulson, 73; Alanja White, 3; Donald Shanor, 67; Quintin “Bill” Moore, 59; and Lynn Williams, 27, and her son John “Critter” Williams, 5.16

Damage Assessment and Economic Impact

The economic devastation of the flood unfolded in stages as the full scope of destruction became apparent. Initial damage estimates proved consistently low as assessors discovered the extent of destruction throughout the city. Property damage estimates varied, with one insurance adjuster reporting his firm had handled claims of over $1 million by mid-morning the day after the flood.17

By August 4, initial damage assessments conducted by FEMA estimated that some 130 homes fell into the “major damaged or destroyed” category, with another 650 living units classified as severely damaged.18 However, as damage surveys continued over the weekend, these figures were revised significantly upward. By August 5, total damage estimates to private homes alone rose to $22.3 million, with 150 private homes or apartments having sustained major damage or been destroyed, and approximately 1,400 homes suffering less severe damage.19

Government facilities experienced extensive damage. The damage to the Police Department was so extensive—more than $300,000—that the city was forced to relocate the entire department, with Mountain Bell agreeing to sell their office building at 2020 Capitol Ave. to the city for $2 million under an arrangement calling for $500,000 initially and the remainder in three installments of $500,000 each.20 Property loss to the Herschler Building alone was estimated at $3.5 million.21

By the time President Ronald Reagan declared Cheyenne a disaster area on August 7, estimates of property loss had been raised to more than $40 million, the highest such loss in the city’s 118-year history.22 The final damage assessment ultimately reached approximately $65 million, making it the most damaging flood in Wyoming history.23

Immediate Rescue Operations and Emergency Response

In the first critical hours following the flood, emergency responders and ordinary citizens launched heroic rescue efforts throughout the city. Wyoming Army National Guard members organized dramatic rescue operations, working through the night to assist those affected by the disaster.

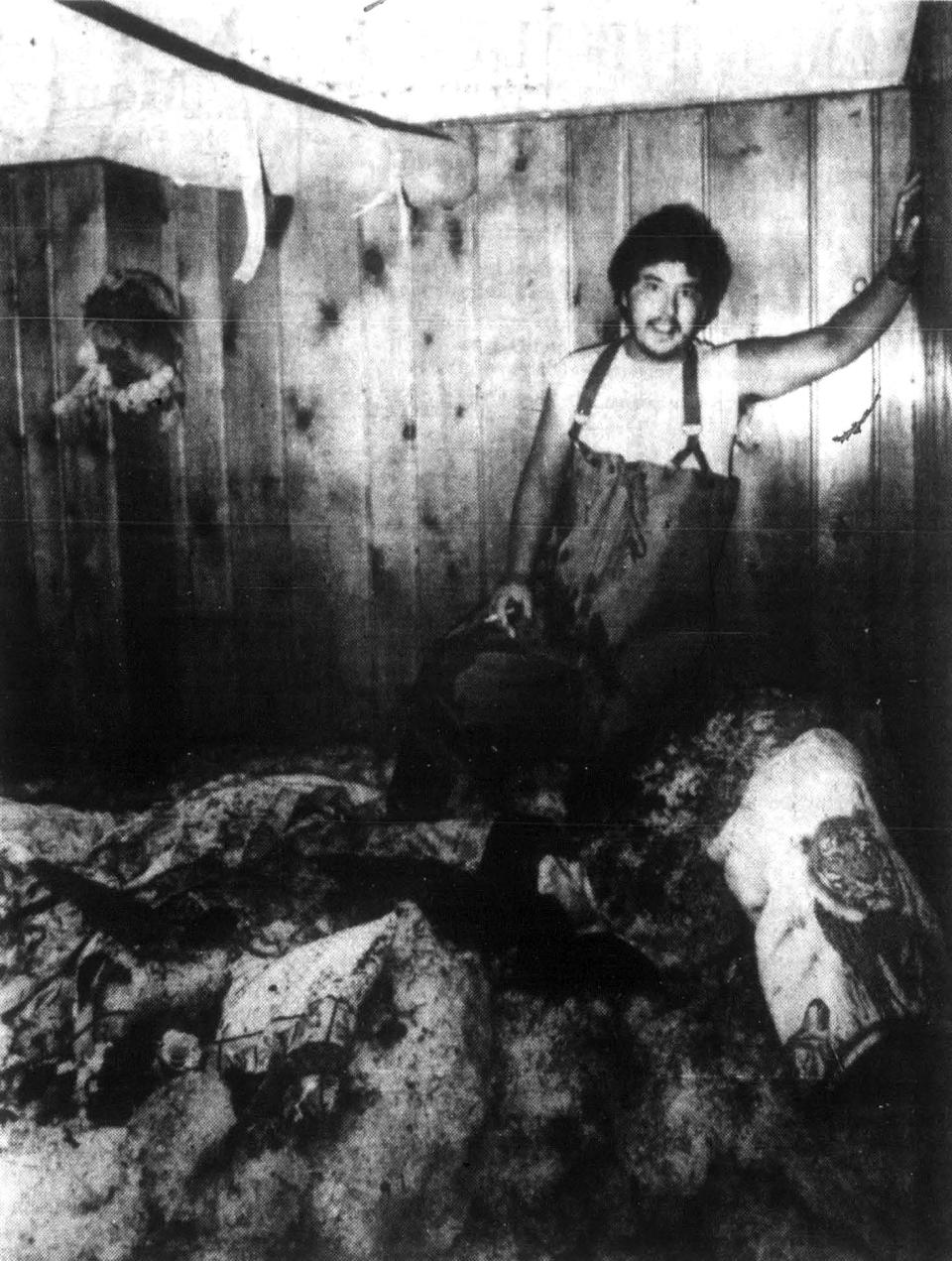

In one notable incident in east Cheyenne’s Lakeview addition, six men chained together and tied to a front-end loader swam to rescue victims, while neighbors set up a makeshift hospital in a garage complete with individual beds and heating pads.24 Neighbors helped rescue stranded residents who had climbed into trees to escape the floodwaters, using boats to ferry them to safety.25

Police Chief Byron “Rook” Rookstool later reflected on the community’s immediate response: “Those people are heroes. Those and the citizens of Cheyenne who worked hand in hand and side by side to restore some semblance of order in the chaos following... It may be a funny way to put it, but Cheyenne was like an ant hill that had been kicked. The citizens literally swarmed out after the flood, not just to look, but to help put their city back together. That was just as beautiful as the flood was awful.”26

Relief Organizations and Disaster Aid

Within hours of the flood, major relief organizations mobilized comprehensive disaster response operations. The American Red Cross mounted a wide-ranging disaster response operation, spending over $300,000 in Cheyenne—all of which was distributed locally to flood victims. The organization deployed 175 volunteers to assist flood victims, 50 percent of whom were from out of town and sent by the National Red Cross organization.27

Red Cross volunteers began manning phone lines the morning after the flood, taking incoming calls from concerned friends and relatives seeking information about Cheyenne residents.28 The aid organization also distributed 500 cleaning kits, blankets, and other emergency supplies to affected residents.29 In addition, they also established a mobile feeding program in affected neighborhoods and set up canteens at Disaster Assistance Centers.

During interviews with flood victims, Red Cross workers discovered that many people, particularly parents, asked only for assistance for their children while ignoring their own needs. Volunteers were trained to “"dig down and uncover needs” that clients felt they couldn’t ask to have supplied, including medical prescriptions, hearing aids, dentures, and prosthetic devices.30

Shelters for homeless victims were set up at the Salvation Army and by the Laramie County Chapter of the American Red Cross at the National Guard Armory. Additionally, a special disaster food stamp program was established for eligible flood victims, with distribution available from August 17 to 30. The program was administered at the old Worker’s Compensation Building and was limited to individuals and families living in designated flood areas. Food stamps were issued on the spot to eligible households with proof of identification and residency.31

Community Volunteers and Long-term Support

The disaster brought out remarkable volunteerism from across the region. Boys from St. Joseph’s Children’s Home in Torrington volunteered their time, working to remove wet carpeting, carry out garbage, and help with whatever was needed in the cleanup effort.32 Four teenagers, dubbed the “Rambo squad,” spent about eight hours a day helping elderly residents with cleanup tasks.33

Recognizing the need for sustained assistance, the reformed Interfaith Disaster Task Force was organized to provide long-term help to flood victims, recognizing that some people do not realize they need help until months later, when federal and state aid is no longer available. Nearly 75 church leaders and lay people met Wednesday morning to determine interest in reforming the task force, which had previously operated for about one and a half years during the 1979 tornado’s aftermath. The organization hoped to provide emotional, financial and moral support to storm victims, with nearly 10 different denominations participating in the program.34

Federal Disaster Declaration and Aid

When President Reagan declared Cheyenne a disaster area, it opened the way for federal assistance to thousands of homeowners as well as for local and state governments to apply for assistance in repairing their homes and public facilities. The state’s two U.S. senators, Malcolm Wallop and Alan Simpson, and Congressman Dick Cheney announced the White House action at mid-morning on August 7. The congressional delegation had sent a letter to Reagan the day after the flood predicting that such a request would be forthcoming and urging expedited White House action and approval.35

Under the two categories of aid provided by federal law, homeowners could apply for up to $5,000 each in assistance in meeting the costs of damage to their homes, most of which had no flood insurance coverage. The other category provided assistance to governmental units such as the city, county and state, for damages caused to streets, bridges and other public facilities.36 However, federal coordinating officer John D. Swanson warned that compensation would not be immediately forthcoming, as losses had to be inspected and verified before assistance could be provided.37

The Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) established a disaster field office in the Aspen Ridge Plaza on Dell Range Blvd. and set up a Service Center to help flood victims complete loan forms and check on the status of aid applications.38 The Small Business Administration also offered low-interest disaster loans to help residents rebuild.39

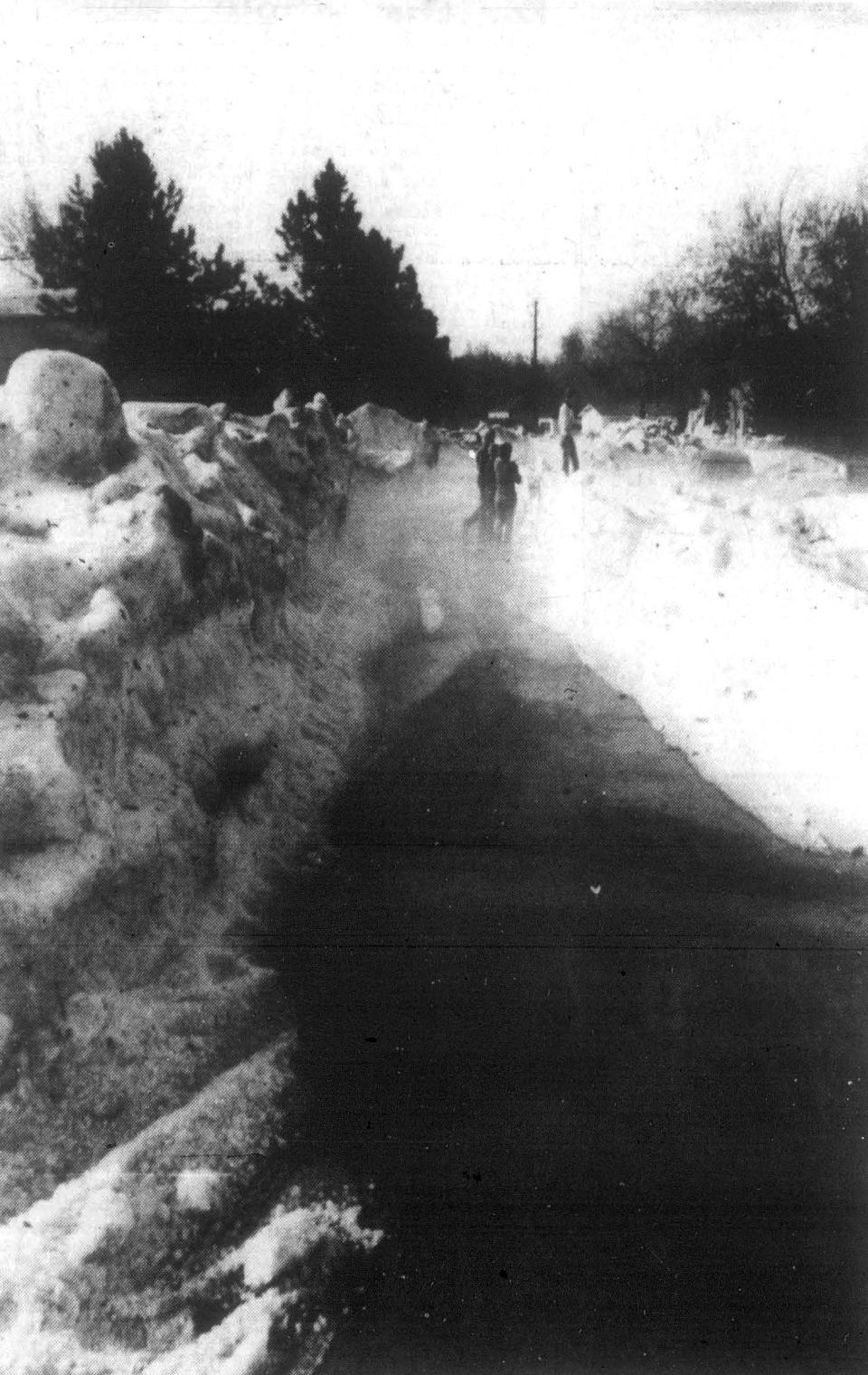

Cleaning Up

The massive cleanup effort began immediately and continued for months. Cheyenne’s sanitation department spent weeks collecting waterlogged furniture, carpets, appliances, and debris from affected neighborhoods. The city provided free debris removal to flood victims, with workers remembering piles of hail that remained six to seven feet tall even a day after the storm.40 Street crews used snowplows to clear hail, leaving mud-covered drifts in some areas as high as 10 feet to make the streets passable. In one basement on East Pershing Boulevard, the hail filled the basement to its 8¼ foot ceiling height.41

Government buildings required extensive restoration work. State maintenance crews began a race against time to remove and replace the boilers from the massively water-damaged underground level of the Herschler State Office Building before cold weather arrived. Most of the building's 722 employees returned to work Tuesday morning, though the air conditioning remained inoperable for the rest of the summer and there was no elevator service.42

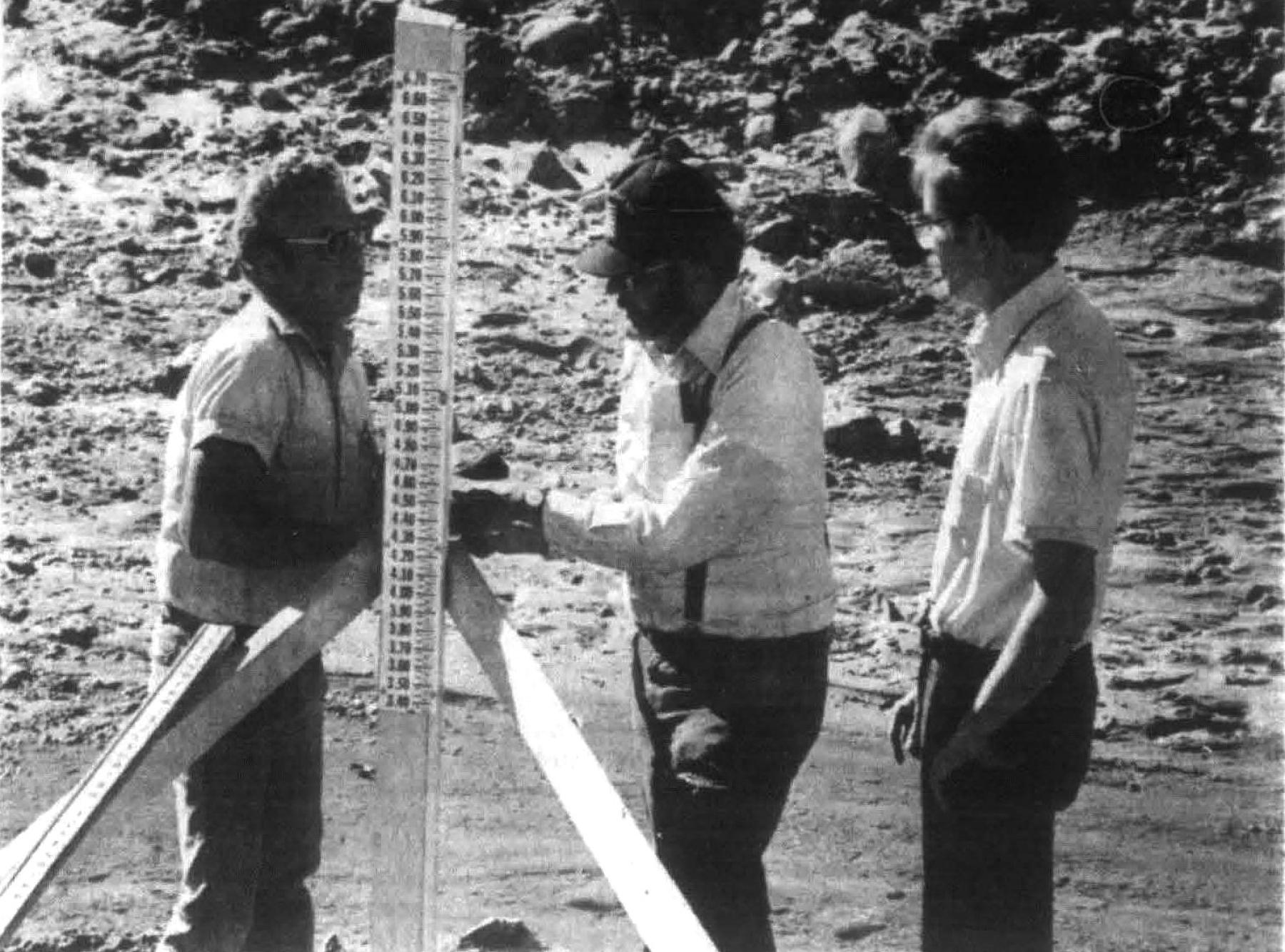

Image

Important paper records belonging to several county offices and private firms, along with a valuable stamp collection, were salvaged using a specialized vacuum drying process. Document Reprocessors of San Francisco brought a large vacuum trailer to Cheyenne’s airport, where approximately 9,000 pounds of water-soaked records were dried over a two-week period beginning August 6. The process successfully restored between 85 and 97 percent of the county records that were essential for ongoing government operations, including auto license records needed by the county treasurer's office.43

Health and safety concerns required immediate attention. The city’s environmental health director, Don Peck, warned that between 900 and 1,000 homes may have experienced sewage backup in their basements or other areas of the dwellings. Pack urged homeowners who have such problems to wear protective clothing and equipment, including disposable rubber gloves and rubber boots.44 Hundreds of water wells outside the city were contaminated by the storm, requiring homeowners to boil drinking water or find alternative sources until wells could be disinfected.45 The Public Health Laboratory requested that all water supplies outside of Cheyenne postpone their routine water testing requests during the week so the lab could concentrate its resources on water samples resulting from the Cheyenne flood.46

Both of the city’s hospitals were affected, with Memorial Hospital’s emergency room flooded and operations moved to the cafeteria, while DePaul Hospital treated approximately 20 emergency patients related to the storm.47

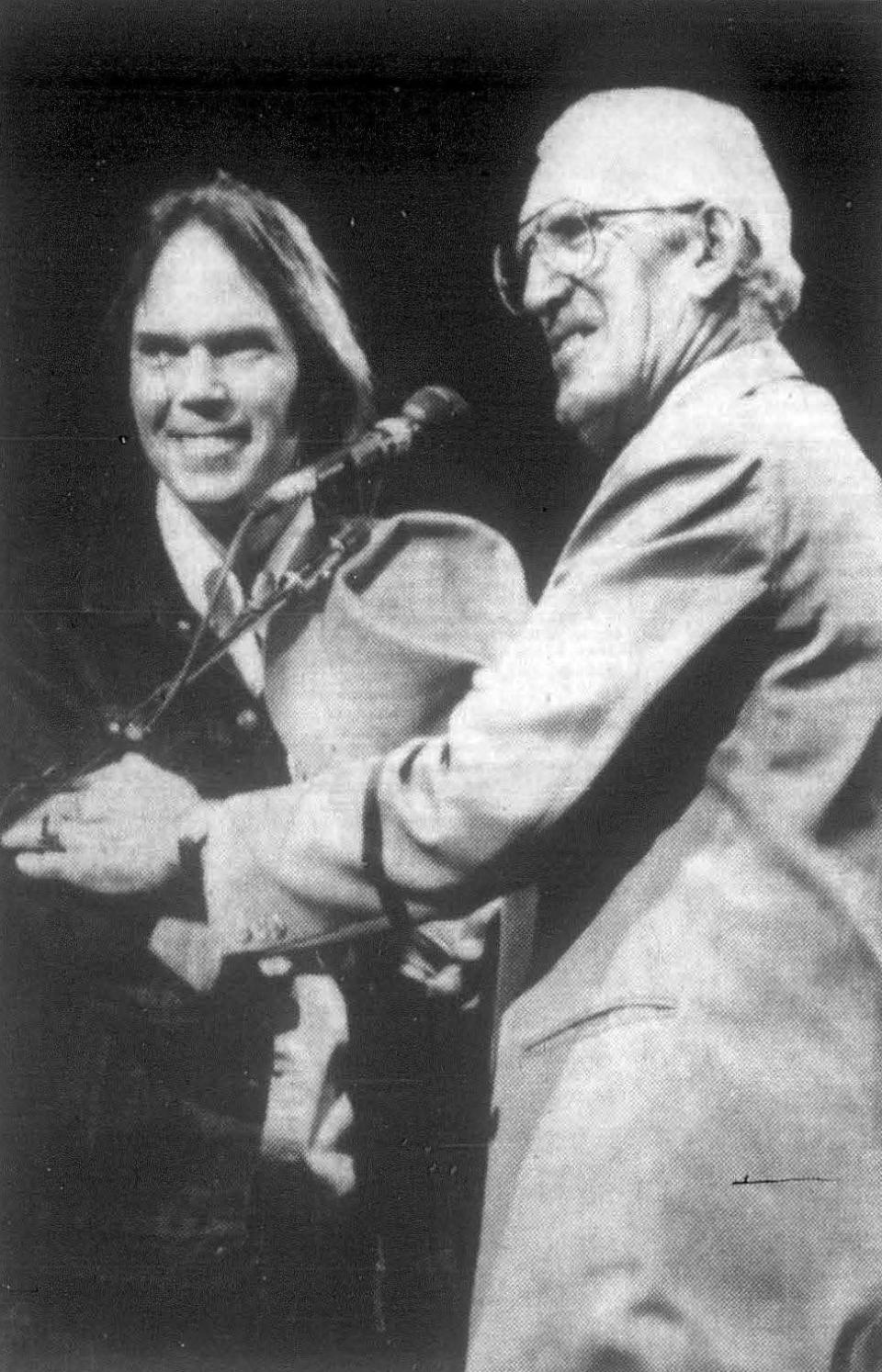

Neil Young Benefit Concert

The community’s resilience and the widespread attention the disaster had garnered was further demonstrated when renowned musician Neil Young volunteered to perform a benefit concert for flood victims. The event was the idea of Jerry Baldwin, Wyoming’s emergency management planner, who conceived of asking Neil Young to perform while sitting in his flooded house.48

The announcement was made at a press conference on August 15 by Wyoming Governor Ed Herschler, who revealed that Young, a member of the former rock group Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, would perform on August 29 at Frontier Park. The Cheyenne Frontier Days Committee donated the use of the park and provided support with ticketing and security. The concert was organized through a non-profit corporation established specifically for the event, with proceeds to be distributed among four Cheyenne agencies: the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, Community Action of Laramie County, and the Interfaith Task Force of Cheyenne.

Local musician Michael DeGreve wrote a song about the flood called “Silver Lining,” which gave the concert its name through a contest held by the Cheyenne Association of Broadcasters.49 Corporate sponsors, which included Apache Corporation, Union Pacific Corporation, Freudenthal Law Offices, the Cheyenne Association of Broadcasters, Mountain Bell, and Mayor Don Erickson, covered Young’s expenses to ensure that all proceeds would go directly to flood victims who were unable to obtain disaster relief from other sources.

Young donated his time for the performance and gave an energetic preview of the benefit concert while performing at Red Rocks amphitheater near Denver, Colorado, on August 25, telling the crowd how Governor Herschler had asked him to appear and how the state had arranged to transport his equipment. Sporting a gold Wyoming pin on his cowboy hat, Young expressed genuine honor at being asked to perform, noting his surprise at being the featured star rather than one of several performers.

Image

A separate benefit auction was organized the day before the concert at the Laramie County fair barn in Frontier Park to offer further assistance to flood victims. The auction featured donated items from local businesses, including round-trip airfare to Las Vegas, box seats to a St. Louis-Chicago Cubs game, and use of a cabin in Wyoming’s Granite Canyon. The event also featured the Budweiser Clydesdales as a special attraction.50 Governor Herschler personally attended the auction, where he purchased three permanents and haircuts for $140, joking that they were for his wife Casey and that he would charge her for them to get his money back.51

Ticket sales moved slowly, which concert organizers attributed to the relatively short notice for scheduling the event.52 The concert ultimately drew about 5,500 people—roughly half capacity of Frontier Park—and raised approximately $60,000 (about $175,000 in today’s dollars) for flood relief. Editorial staff of The Wyoming Eagle concluded: “The music was great and a lot of money was raised for flood relief... That’s not bad for an effort that was only put together three weeks ago.”53

More detailed accounting later revealed that the benefit effort raised a total of $136,365.50, with only $18,583.24 (13 percent) going to expenses. A total of $117,772.24 was distributed to four Cheyenne public service organizations: the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the Interfaith Recovery Task Force, and Community Action of Laramie County between September 19, 1985, and May 20, 1986.54

Lasting Changes and Flood Mitigation

The 1985 flood fundamentally changed how Cheyenne approached flood management and urban planning. Recognizing that such extreme weather events could occur again, city officials and engineers used the disaster as a catalyst for comprehensive improvements to the city’s flood mitigation infrastructure.55

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, an Inter-Agency Hazard Mitigation Team comprising 14 federal, state and city officials toured the areas of Cheyenne hardest hit by the flood to make recommendations for preventing similar damage in the future. The team, organized only three years earlier, was making its first visit to Cheyenne with the goal of developing cost-effective mitigation measures. Team leader Clancy Philipsborn noted that “almost $4 million is spent each year on flood damage” and emphasized the importance of working with local officials to identify prevention strategies that could save both government and individual homeowner costs in future disasters.56

FEMA released a 44-page Interagency Hazard Mitigation Report on August 26 with recommendations aimed at reducing future damages caused by severe flooding. The team of 38 federal, state and local officials estimated that total losses from the storm could approach $40 million. The report made recommendations in six key areas: protection of critical facilities, communication and warnings, stormwater management, floodplain management, interagency coordination, and public education.57

In the late 1980s, the city developed new drainage master plans and significantly updated drainage regulations. These planning documents were directly informed by the lessons learned from the 1985 flood and identified the most flood-prone areas throughout the city.58

Ongoing mitigation efforts have included the construction of retention ponds, bypass channels, and other engineering solutions designed to handle extreme precipitation events. Notable projects include significant work on Dry Creek, where a new channel was constructed around the Cheyenne Regional Airport runway and behind commercial developments to relieve pressure on the heavily damaged “Sheridan Reach” of Dry Creek.59

The flood also exposed vulnerabilities in existing infrastructure and led to legal challenges. Nearly 50 Sun Valley residents filed suit against the Union Pacific Railroad, claiming that a drainage culvert installed by the railroad to replace an old trestle was inadequate. The residents alleged that an 18-by-20 foot trestle that allowed proper drainage was replaced with a five-foot culvert just prior to the flood, creating a bottleneck that caused “backwater flooding” in the Henderson drainage area.60

The city also integrated flood mitigation considerations into all major street reconstruction projects, with storm sewer improvements becoming a standard component of infrastructure upgrades, particularly in the downtown area that was so severely affected in 1985.61

By 1991, six years after the flood, the city had made substantial progress on flood mitigation efforts. The 911 telephone system and police department were relocated to higher ground, an early warning system was installed to monitor creek levels and precipitation, and emergency communication systems were improved. However, upgrading the stormwater management system remained the most challenging and expensive aspect of flood prevention.62

Image

Ten years after the flood, the city had completed a master drainage plan detailing about $88 million in needed drainage projects. However, only about $10 million had been spent directly on drainage improvements due to funding limitations. City Engineer Jim Harker noted that if a similar flood occurred, “the general public probably would not see a whole lot of difference.”63

Historical Significance

The 1985 Cheyenne flood was not an isolated event in the city’s history, but rather the most recent and best-documented of several major floods that have struck the area. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, Cheyenne has experienced what engineers would classify as three “100-year floods” in the past 50 years. On two occasions—in June 1935 and August 26, 1955—large floods occurred in the downstream reaches of Dry Creek of approximately the same magnitude as the August 1, 1985, flood. The crucial difference was the lack of population in the flooded areas during the earlier storms.64

Earlier significant floods in Cheyenne’s history include events on July 15, 1896 (when 4.7 inches of precipitation fell), May 20, 1904 (intense rain and hail causing flooding along upstream Crow Creek Valley), 1918 (another large flood in downstream Dry Creek reaches), and other notable floods in 1926, 1929 (three separate events), 1946, and 1972. However, due to limited documentation of these earlier floods, a 1977 hydrology study conducted by FEMA completely disregarded the 1935 and 1955 floods when assessing the area’s flood risk.65

The 1985 Cheyenne flood remains the most damaging flood in Wyoming’s recorded history. Weather officials described it as a “once in 100 or 200 years” storm, highlighting the exceptional nature of the meteorological conditions that produced such devastating results.66

The disaster serves as a stark reminder of the power of nature and the vulnerability of urban areas to extreme weather events. It also demonstrates the importance of community preparedness, emergency response capabilities, and long-term planning for natural disaster mitigation.

Today, a memorial plaque bearing the names of the twelve flood victims stands at Ridge Road and Dell Range Boulevard, accompanied by a bronze statue of a great blue heron—a symbol of vigilance and the power of water. This memorial ensures that the lives lost and lessons learned from that tragic evening in 1985 will not be forgotten.67

Editor's note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, whose support helped make the publication of this article possible.

Images Courtesy of USGS and the Wyoming State Tribune.

Resources

Primary Sources

Cheyenne Newspapers (1985-1995)

- The Wyoming Eagle, Wyoming State Tribune, Wyoming Sunday Tribune-Eagle, Wyoming Tribune-Eagle

- Cartie, Kevin. “Unusual Upslope System Here Cause of Series of Thunderstorms.” State Tribune, August 2, 1985.

- Drake, Kerry. “Flood of '85 One of Best Documented in U.S.” Cheyenne Sunday Magazine, May 25, 1986; “Neil Young Gives Preview of Silver Lining Benefit Concert." State Tribune, August 26, 1985; “Neil Young’s ‘Silver Lining’ Concert Is Celebration of Life.” State Tribune, August 30, 1985.

- Flinchum, James M. “Cheyenne Declared Disaster Area.” State Tribune, August 7, 1985; “Power Outages Spotty; Crews Working to Restore Gas, Lights.” State Tribune, August 2, 1985; “State Crews Race to Install Herschler Building Boilers.” State Tribune, August 6, 1985.

- Gorges, Mary. “Long-Term Flood Relief Offered: Interfaith Task Force Organized.” Eagle, August 8, 1985; “Report on Flood Hopes to Prevent Damage in Future.” Eagle, August 27, 1985; “Team Studies Flood.” Eagle, August 14, 1985.

- Knox, Kirk. “10 Dead, 70 Injured, 2 Still Missing in Record Storm Here.” State Tribune, August 2, 1985; “County Records In Flood Usable.” State Tribune, August 22, 1985; “Report Details Van Alyne’s Heroic Rescue Effort.” State Tribune, August 17, 1985.

- Lewis, Tony. “Sun Valley Lawsuit Finally Goes to Trial.” Eagle, August 1, 1986.

- Miller, Lee. “Governor Signs Request for Aid.” Wyoming Sunday Tribune-Eagle, August 4, 1985.

- Putnam, C.J. “Flood Victims Won't Get Federal Aid Immediately Upon Applying.” State Tribune, August 8, 1985; “It's Pump-out, Mop-up Time for Many Residents.” State Tribune, August 3, 1985; “Mourners Fill Church to Honor Drowned Officer.” State Tribune, August 5, 1985; “Violent Storm Leaves Wide Path of Destruction in City.” State Tribune, August 2, 1985.

- Sauer, Linda. “FEMA Briefs Local Officials on Federal Flood Aid.” Eagle, August 9, 1985; “Good Samaritans Find Work Difficult But Very Rewarding.” Eagle, August 6, 1985.

- Schultz, Carolyn. “Lack of funds has hampered plans for drainage projects.” Wyoming Tribune-Eagle, August 1, 1995.

- Stewart, Jim. “Silver Lining Concert Raises About $60,000.” Eagle, August 30, 1985.

- Woolsey, Mary K. “Water in the Squad Room: Summer Evening Erupts Into Nightmare.” SunDAY Magazine, September 1, 1985; “’We Dig Down and Uncover Needs’: When Disaster Strikes, Red Cross Acts.” SunDAY Magazine, September 22, 1985.

- Multiple unsigned articles from The Wyoming Eagle and Wyoming State Tribune, August 1985-October 1986.

Government Sources

- National Weather Service Cheyenne. “August 1985 Cheyenne Flood.” https://www.weather.gov/cys/August1985CheyenneFlood.

Secondary Sources

- Chilton, James. “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.” Wyoming News, July 31, 2015. https://www.wyomingnews.com/news/remembering-the-flood-of-1985-in-cheyenne/article_6c79cdb0-8d3d-5f55-8051-19f2ff0d8423.html.

- Downing, Jeremy. “On The 30th Anniversary: Cheyenne Remembers the Deadly Flood of 1985.” Wyoming News Now, July 31, 2015. https://www.wyomingnewsnow.tv/news/on-the-30th-anniversary-cheyenne-remembers-the-deadly-flood-of-1985/article_4df4afd0-bd43-5896-a5e3-2b71aad82d78.html.

- Hirst, Greg. “(Aug. 1, 1985): 12 fatalities as deadly storm floods Cheyenne.” Oil City News, August 1, 2020. https://oilcity.news/community/backstory/2020/08/01/aug-1-1985-12-fatalities-as-deadly-storm-floods-cheyenne/.

Footnotes

-

Jeremy Downing, “On The 30th Anniversary: Cheyenne Remembers the Deadly Flood of 1985,” Wyoming News Now, July 31, 2015, updated September 26, 2024, https://www.wyomingnewsnow.tv/news/on-the-30th-anniversary-cheyenne-remembers-the-deadly-flood-of-1985/article_4df4afd0-bd43-5896-a5e3-2b71aad82d78.html; National Weather Service Cheyenne, “August 1985 Cheyenne Flood,” accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.weather.gov/cys/August1985CheyenneFlood.

2. James Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne,” Wyoming News, July 31, 2015, updated January 4, 2016, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.wyomingnews.com/news/remembering-the-flood-of-1985-in-cheyenne/article_6c79cdb0-8d3d-5f55-8051-19f2ff0d8423.html.

3. Kevin Cartie, “Unusual Upslope System Here Cause of Series of Thunderstorms,” Wyoming State Tribune, August 2, 1985, 1.

4. Kirk Knox, “10 Dead, 70 Injured, 2 Still Missing in Record Storm Here,” State Tribune, August 2, 1985, 1.

5. National Weather Service Cheyenne, “August 1985 Cheyenne Flood;” Cartie, “Unusual Upslope System Here.”

6. Ibid.; Greg Hirst, “(Aug. 1, 1985): 12 fatalities as deadly storm floods Cheyenne,” Oil City News, August 1, 2020, accessed June 14, 2025, https://oilcity.news/community/backstory/2020/08/01/aug-1-1985-12-fatalities-as-deadly-storm-floods-cheyenne/; Knox, “10 Dead, 70 Injured, 2 Still Missing”; “Water Turns Streets to Rivers,” The Wyoming Eagle, August 2, 1985, 1.

7. Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

8. Downing, “On The 30th Anniversary.”

9. C.J. Putnam, “Violent Storm Leaves Wide Path of Destruction in City,” State Tribune, August 2, 1985, 2.

10. Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

11. James M. Flinchum, “Power Outages Spotty; Crews Working to Restore Gas, Lights,” State Tribune, August 2, 1985, 1.

12. C.J. Putnam, “It’s Pump-out, Mop-up Time for Many Residents,” State Tribune, August 3, 1985, 1.

13. National Weather Service Cheyenne, “August 1985 Cheyenne Flood.”

14. Kirk Knox, “Report Details Van Alyne’s Heroic Rescue Effort,” State Tribune, August 17, 1985, 1.

15. C.J. Putnam, “Mourners Fill Church to Honor Drowned Officer,” State Tribune, August 5, 1985, 1.

16. Knox, “10 Dead, 70 Injured, 2 Still Missing”; “12 Victims Found; All Missing Accounted For,” Eagle, August 3, 1985, 1; multiple obituaries in State Tribune, August 2-3, 1985; Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

17. Knox, “10 Dead, 70 Injured, 2 Still Missing.”

18. Lee Miller, “Governor Signs Request for Aid.” Wyoming Sunday Tribune-Eagle, August 4, 1985, 1.

19. “Residential Damage $22.3 Million,” Eagle, August 5, 1985, 1.

20. “City Purchases Bell Building,” Eagle, August 8, 1985, 1.

21. James M. Flinchum, “State Crews Race to Install Herschler Building Boilers,” State Tribune, August 6, 1985, 1.

22. James M. Flinchum, “Cheyenne Declared Disaster Area,” State Tribune, August 7, 1985, 1.

23. Downing, “On The 30th Anniversary.”

24. Putnam, “Violent Storm Leaves Wide Path of Destruction.”

25. Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

26. Mary K. Woolsey, “Water in the Squad Room: Summer Evening Erupts Into Nightmare,” SunDAY Magazine, supplement to Wyoming Sunday Tribune-Eagle, September 1, 1985, 6, 7.

27. Mary K. Woolsey, “’We Dig Down and Uncover Needs’: When Disaster Strikes, Red Cross Acts,” SunDAY Magazine, September 22, 1985, 7.

28. Putnam, “It’s Pump-out, Mop-up Time.”.

29. Woolsey, “’We Dig Down and Uncover Needs.’”

30. Ibid.

31. “Flood Victims May Pick Up Food Stamps,” State Tribune, August 17, 1985, 2.

32. Linda Sauer, “Good Samaritans Find Work Difficult But Very Rewarding,” Eagle, August 6, 1985, 1.

33. “Organized System Begins Aid to Disaster Victims,” Eagle, August 12, 1985, 1.

34. Mary Gorges, “Long-Term Flood Relief Offered: Interfaith Task Force Organized,” Eagle, August 8, 1985, 14

35. Flinchum, “Cheyenne Declared Disaster Area.”

36. Ibid.

37. C.J. Putnam, “Flood Victims Won't Get Federal Aid Immediately Upon Applying,” State Tribune, August 8, 1985, 1.

38. Linda Sauer, “FEMA Briefs Local Officials on Federal Flood Aid,” Eagle, August 9, 1985, 1.

39. “SBA Urges Local Storm Victims to Apply for Disaster Loans Now,” State Tribune, August 24, 1985, 2.

40. Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

41. Putnam, “It’s Pump-out, Mop-up Time.”.

42. James M. Flinchum, “State Crews Race to Install Herschler Building Boilers,” State Tribune, August 6, 1985, 1.

43. Kirk Knox, “County Records In Flood Usable,” State Tribune, August 22, 1985, 1.

44. “Exposure to Sewage Is Health Problem Here,” State Tribune, August 5, 1985, 1.

45. “Hundreds of Water Wells Contaminated by Storm,” State Tribune, August 7, 1985, 1.

46. “Public Health Lab Delays Routine Water Testing,” State Tribune, August 6, 1985, 2.

47. “Memorial, DePaul Go to Emergency Generators,” State Tribune, August 2, 1985, 1.

48. “Community to Honor ‘Silver Lining’ Volunteers,” Sunday Tribune-Eagle, October 26, 1986, 1, 8.

49. Ibid.

50. “Auction Will Benefit Flood Victims,” Sunday Tribune-Eagle, August 25, 1985, 2.

51. “Horses Pull for Flood Aid,” Eagle, August 29, 1985, 1.

52. Kerry Drake, “Neil Young Gives Preview of Silver Lining Benefit Concert,” State Tribune, August 26, 1985, 1.

53. Kerry Drake, “Neil Young’s ‘Silver Lining’ Concert Is Celebration of Life,” State Tribune, August 30, 1985, 6; Jim Stewart, “Silver Lining Concert Raises About $60,000,” Eagle, August 30, 1985, 1; “It Was A Great Show,” Eagle, August 31, 1985, 4.

54. “Community to Honor ‘Silver Lining’ Volunteers.”

55. Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

56. Mary Gorges, “Team Studies Flood,” Eagle, August 14, 1985, 1.

57. Mary Gorges, “Report on Flood Hopes to Prevent Damage in Future,” Eagle, August 27, 1985, 1.

58. Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

59. Ibid.

60. Tony Lewis, “Sun Valley Lawsuit Finally Goes to Trial,” Eagle, August 1, 1986, 1, 15.

61. Chilton, “Remembering the flood of 1985 in Cheyenne.”

62. “Cheyenne has not ignored flash flood recommendations,” State Tribune, August 1, 1991, 11.

63. Carolyn Schultz, “Lack of funds has hampered plans for drainage projects,” Wyoming Tribune-Eagle, August 1, 1995, A5.

64. Kerry Drake, “Flood of ‘85 One of Best Documented in U.S.,” Cheyenne Sunday Magazine, May 25, 1986, 8.

65. Ibid.

66. Hirst, “(Aug. 1, 1985): 12 fatalities as deadly storm floods Cheyenne.”

67. Downing, “On The 30th Anniversary.”