- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Pumping Water To Powering Homes: Harnessing Wyo...

Pumping Water to Powering Homes: Harnessing Wyoming’s Wind

When an expedition led by explorer John C. Fremont camped along the North Platte River in 1842, it was greeted by a force of nature that throughout time has vexed visitors and residents alike: Wyoming’s strong and often relentless wind.

Little did Charles Preuss, a German mapmaker with the group, realize that the simple act of raising ground pins for a tipi would invite a minor calamity.

“At this instant,” Fremont recalled, “and without warning until it was within 50 yards, a violent gust of wind dashed down the lodge, burying under it Mr. Preuss and about a dozen men, who had attempted to keep it from being carried away.”

Despite such misadventures, the Wyoming wind also can be a boon, that when harnessed, has proven to be an asset to both home and industry.

By 2014, Wyoming ranked 14th nationally in terms of wind projects online with 24, and the state had 1,410 megawatts of installed capacity, according to the American Wind Energy Association. That’s about twice as much electricity as a large, coal-fired power plant is likely to produce. On the horizon, one wind project alone was expected to produce up to 3,000 megawatts of electricity.

Windmills pump water for railroads

With the coming of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1867, the Union Pacific used windmills to supply water for its steam locomotives.

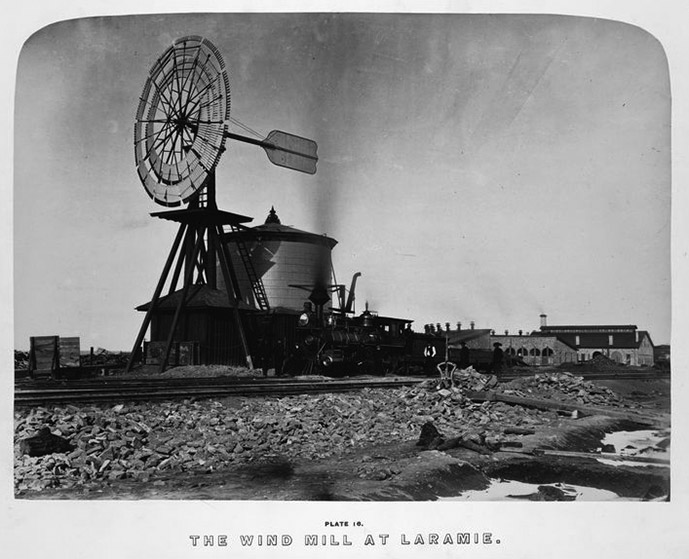

A large windmill, an associated water tank and a 20-stall roundhouse were constructed in Laramie, Wyoming Territory. The windmill’s blades spun in a circle 20 feet in diameter; the tank could hold 50,000 gallons of water and took about 10 hours to fill. Similar windmills were erected at other stations, including Sherman and Cheyenne.

These early industrial models, known as Halladay windmills, were named for Daniel Halladay, a Connecticut mechanic who developed them for pumping water and other uses. His invention automatically adjusted to wind direction and controlled the speed of the wind wheel.

Halladay patented his self-governing windmill in 1854. His company eventually relocated to Illinois in order to better serve a rapidly growing market for his products in the West.

|

Halladay’s U.S. Wind Engine & Pump Co. became a major supplier of windmills for both industrial and agricultural use. The models used by the Union Pacific were designed to withstand heavy winds that frequently blow across the high plains.

Floyd Heavener, an early Laramie resident, mentioned in the Laramie Sentinel of Oct. 25, 1879, as a foreman in the Union Pacific Car Department, may have been inspired by the railroad’s grand structures to design a windmill of his own.

“On Saturday last,” the Laramie Sentinel reported on May 9, 1879, “Mr. Floyd Heavener of our city, left for Chicago to look after the construction of his model windmill. Floyd is an enterprising and inventive genius, and will make a success out of some of his projects yet.”

It’s not clear if Mr. Heavener’s trip bore fruit.

Windmills pump water for agriculture

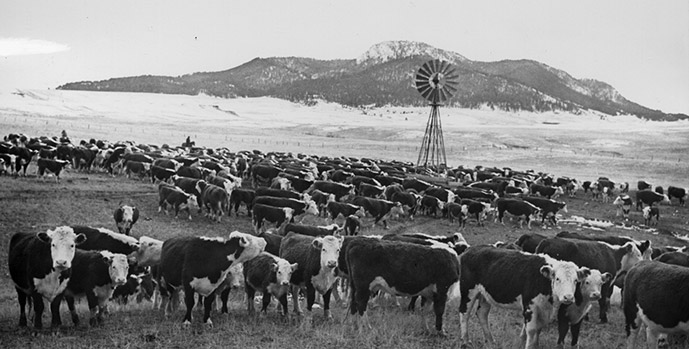

Windmills for pumping water also made ranching possible in vast areas where moisture was scarce and streams were few or ephemeral. Water yielded by windmills helped to open thousands of acres for livestock.

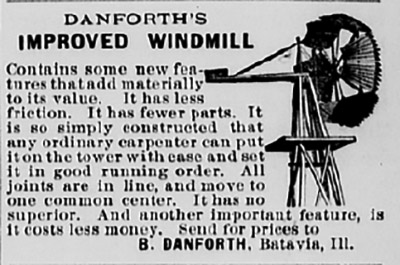

A December 24, 1886 advertisement in the Cheyenne-based Northwestern Live Stock Journal touted the benefits of a new and improved windmill manufactured by the Danforth Windmill Co.

The revamped machine not only experienced less friction, the company claimed, but it contained fewer parts as well. “It is so simply constructed that any ordinary carpenter can put it on the tower with ease and set it in good running order,” the ad said. “It has no superior.”

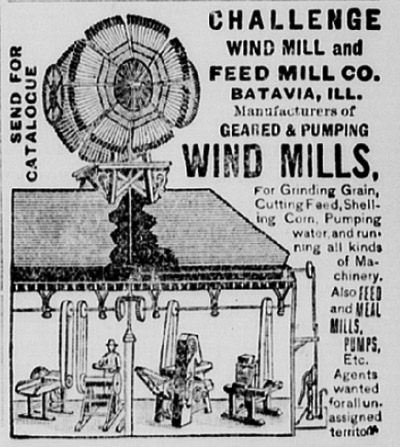

Danforth Windmill was based in Batavia, Ill., at the time a hub of windmill manufacturing. The city also hosted the U.S. Wind Engine & Pump Co., makers of the large railroad models.

Cheap windmills made mostly of wood became common sights in the West. These were either built by settlers or purchased from one of many manufacturers. Some larger models could draw water from depths of 100 meters.

“Dry farming is receiving much attention and it is a fact that within five miles of Laramie there is one man who for the past three years has supported a large family upon the income derived from a plot of forty acres of land, upon which the only water obtained is from a well and a windmill of home construction,” the Laramie County Times reported on June 24, 1905.

Over time, metal replaced wood as the construction material of choice. An Aermotor advertisement noted sales of 45 steel windmills in 1888, which increased to 60,000 in 1892.

Wind powers home-based electric plants

The 1920s witnessed the spread of small systems intended to produce electricity. Prior to World War I, electrical power was rare in rural America. But entrepreneurs like Charles Franklin Kettering, a founder of the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Co. (Delco), were determined to electrify the hinterlands.

Kettering and his team at the Domestic Engineering Co. introduced a Delco Light “farm electric plant.”

So-called wind chargers adapted two- or three-blade configurations that originally had been developed for aircraft. The first units were simple machines with attached propellers that could charge a radio battery and power a light bulb or two.

Eventually, some large wind chargers generated reasonably large quantities of power. “The companies began supplying their wind electric plants with a slightly larger capacity battery to make this possible where fuel was difficult to obtain or undesirable,” according to Windcharger.org, a website on the history of the wind charger industry.

Large wind chargers were designed to compete with or complement farm electric plants.

Early farm electric plants typically used generators that ran on kerosene or home heating fuel. “For farms that added a wind charger to an existing farm electric plant, the effect was to reduce fuel consumption and engine operating time, and thus extend the life expectancy of the (unit) significantly,” the Windcharger.org website points out.

When the battery charges fell below a preset level, the engine would start up. It would shut off once the batteries were recharged. Once fully charged, the system reputedly could power a house for several days.

In one memorable incident reported by the Douglas Enterprise on April 27, 1920, a school play was in danger of being postponed because the Douglas Electric Light Co. plant was shut down: “This predicament was overcome by Bert Thompson and Jesse Morsch who, when advised that such action would likely be taken, installed a Delco system.”

Electric companies often concluded that serving rural areas was impractical. By the early 1930s, wind chargers and Delco Light plants remained popular. But in 1935, the federal government embarked on an ambitious effort through the Rural Electrification Administration to extend the electrical grid to rural areas, thereby greatly reducing the need for small systems to generate power.

By the early 1950s, most Wyoming farms and ranches were electrified, thanks to the REA. Some windmills were still used for pumping livestock water, but rarely to produce power.

The use of wind power also fluctuated with the price of fossil fuels. As prices declined after World War II, interest in wind power likewise diminished.

Then, in the 1970s, a renaissance in wind energy resulted from an international market shock. In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries imposed an oil embargo. The price of crude quadrupled in a matter of weeks.

In the U.S., dependence on foreign oil became a matter of urgent concern. A search for alternatives prompted, among other things, accelerated research into wind and solar power. In a televised speech on April 18, 1977, President Jimmy Carter called the search for national energy independence “the moral equivalent of war.”

Wind turbines built in Medicine Bow

One metaphorical shot in this struggle was fired in Wyoming. On Sept. 4, 1982, Medicine Bow Mayor Gerald Cook proclaimed Wind Turbine Day in his community.

|

Dignitaries at the event, including U.S. Sen. Malcolm Wallop (R-Wyo.), Gov. Ed Herschler (D-Wyo.) and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Robert Broadbent, praised the Medicine Bow Wind Energy Project and dedicated its two wind turbines.

The event came exactly 100 years after the Edison Illuminating Company’s Pearl Street Station in New York City, the nation’s first central electric-generating system, began serving homes and businesses.

One turbine, a $6 million WTS-4 designed and built by Hamilton Standard, was the largest wind platform in the world in terms of both physical size and power output. The turbine stood 391 feet tall with its two blades fully extended and could generate 4 megawatts of electricity.

The second, a $4 million MOD-2 built by Boeing Engineering and Construction Co., stood 350 feet high with two blades extended and could generate 2.5 megawatts.

Combined, the two turbines could provide electricity for an estimated 3,000 homes, or about 9,000 people.

The Medicine Bow project was a joint demonstration effort of the Bureau of Reclamation, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Lewis Research Center and the U.S. Department of Energy. The hope was to tie as many as 852 wind turbines in with existing hydroelectric plants on the Green and Colorado rivers.

But it wasn’t long before this foray into industrial-scale wind farming faced major problems. The MOD-2 operated sporadically for 18 months before a main-bearing breakdown halted it for good. In 1987, the Bureau of Reclamation sold the unit for $30,000 to a scrap metal dealer.

The Hamilton Standard turbine did better, producing electricity until 1986, when a loose bolt disabled the generator. Bill Young, a local engineer, bought the unit for $20,000 in 1989. He repaired the machine and intermittently operated it as the “Medicine Bow Energy Company.”

Ironically, the Hamilton Standard unit was finally torn apart by strong winds in 1994.

Wind power develops into large industry

But the demise of the Medicine Bow project marked a beginning more than an end.

Increasingly, changes in the energy landscape paved the way for large utility companies to build major wind projects.

The American Wind Energy Association noted that wind energy became increasingly cost competitive. Supportive federal policies allowed wind developers to scale up their efforts. A renewable energy production tax credit assisted projects undertaken by the end of 2013, which resulted in a wind energy construction boom.

In Wyoming, purchases of wind energy equipment for a time were exempt from sales and use taxes.

Electric utilities also began viewing wind energy as a long-term, fixed-price hedge against more volatile energy prices that resulted from electrical generation using fossil fuels. Several states also required energy companies to provide a portion of their energy needs from renewal sources like wind and solar.

In Wyoming, PacifiCorp/Rocky Mountain Power embarked on a major wind energy program, taking advantage of the state’s favorable wind profile and the proximity of project sites to existing transmission lines.

The company’s first project–Foote Creek I located near Arlington in Carbon County–went into service on Earth Day in 1999 and consisted of 69 turbines. Foote Creek I was the first utility-scale wind project in the state.

PacifiCorp subsequently constructed eight additional wind farms following the 2006 acquisition of the company by MidAmerican Energy Holdings Co. (now Berkshire Hathaway Energy Co.). Three projects–Glenrock, Rolling Hills and Glenrock III–are located on the site of the reclaimed Dave Johnston coal mine near Glenrock in Converse County.

In 2014, six of the company’s nine wind projects were located in Carbon County (two of which also included wind turbines in Albany County). In addition to Foote Creek I, these were Seven Mile Hill and Seven Mile Hill II between Medicine Bow and Hanna, Wyo., both placed in service in 2008; High Plains southwest of Rock River, Wyo., which started up in 2009; McFadden Ridge I southwest of Rock River, also started in 2009; and Dunlap I near Medicine Bow, started in 2010.

State taxes wind-power production

Wyoming became the first state to levy a tax on wind energy output. In 2012, the $1-per-megawatt-hour tax yielded about $2.6 million to county and state coffers. Despite concerns the tax might dampen wind development, a legislative committee voted against making changes to the law.

The production tax apparently had little impact on plans for the huge Chokecherry-Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project in Carbon County south of Rawlins, Wyo. Up to 1,000 turbines would make it the largest wind farm in the U.S. Phase 1 construction of about 500 turbines was expected to begin in late 2014 and continue through much of 2018.

When completed, the Power Company of Wyoming project is expected to produce between 2,500 and 3,000 megawatts of electricity, most of which would be destined for customers in the Desert Southwest. Company officials estimated the project could provide power for about one million households.

Power Company of Wyoming is a wholly owned affiliate of The Anschutz Corporation and Denver billionaire Philip Anschutz.

Wind industry eyes manufacturing growth

In addition to wind-energy generation, a study commissioned by the Casper Area Economic Development Alliance (CAEDA) in 2008 weighed the feasibility of developing local manufacturing related to wind energy.

Officials from Business Facility Planning Consultants of Norcross, Ga., felt that turbine manufacturing could be a good fit for Casper, in part because of plans to build a large network of wind farms in the state.

“Casper’s benefits for this industry include the regional demand for turbines, its good rail connections for inbound supplies and to ports for exporting, its moderate cost for the large amount of electricity needed in fabricating equipment, and the skills available in the regional workforce relevant to assembling such equipment,” the consultants’ report said.

By 2014, however, no such turbine-manufacturing sector had materialized.

Resources

- American Wind Charger Industry. ”American Wind Charger Industry 1916 to 1960.” Accessed June 11, 2014, at http://www.windcharger.org/Wind_Charger/Welcome.html.

- American Wind Energy Association. “State fact sheets.” Accessed June 12, 2014, at http://www.awea.org/resources/statefactsheets.aspx?itemnumber=890.

- Bailey, James. “The Medicine Bow Wind Energy Project,” U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (2014), 1-6.

- Business Facility Planning Consultants “Recommendations of Marketing Targets.” Report prepared for the Casper Area Economic Development Alliance, (2008), 14-15.

- Choquette, Kara, Power Company of Wyoming, director of communications. Email communications with author, May 2014.

- Dodge, Darrell M. “Illustrated History of Wind Power Development.” Accessed June 11, 2014, at http://telosnet.com/wind/.

- Hymas, Jeff, Rocky Mountain Power, senior communications specialist. Email communications with author. May 2014.

- Industrial Siting Division, State of Wyoming. “Notice of request for a permit and hearing.” related to Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project. Cheyenne: May 12, 2014.

- Kelley, Peter, American Wind Energy Association, vice president of public affairs. Email communications with author. May 2014.

- McManus, Leslie C. “A Windmill Town Celebrates Local Heritage,” Farm Collector, December 2012. Accessed June 12, 2014 at http://www.farmcollector.com/equipment/windmill-town-zmmz12deczbea.aspx.

- Northwestern Live Stock Journal, “Danforth’s improved windmill advertisement,” December 24, 1886.

- “Seniors Merit Praise for Splendid Presentation of Comedy at Princess Friday,” Douglas Enterprise, April 27, 1920, 1.

- “Wyoming’s Resources: Wyoming Ranches Pay Well,” Laramie County Times, June 24, 1905, 1.

- “Windmills,” Laramie Sentinel, May 9, 1879, 1.

- “Railroad employes [sic],” Laramie Sentinel, Oct. 25, 1879, 1.

- Righter, Robert. "Wind at Work in Wyoming." Annals of Wyoming 61, no. 1 (1989): 32-38.

- Union Pacific Railroad Museum staff, Council Bluffs, Iowa, email communications with author, May 2014.

- U.S. Department of the Interior. Bureau of Land Management. “Wind Energy: Fact Sheet and Map.” Accessed June 11, 2014, at http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/energy/wind_energy.html.

- Voge, Adam. “First year of Wyoming wind tax blows in $2.6 million,” Casper Star-Tribune, March 14, 2013, http://trib.com/news/state-and-regional/first-year-of-wyoming-wind-tax-blows-in-million/article_ab416dcc-3b59-5325-b6f6-4982ed43b4bd.html.

- Wichmann, Kimber. Wyoming Industrial Siting Division, principal economist. Email communications with author, May 2014.

- Zichal, Heather. “A Record Year for the American Wind Industry.” U.S. Department of Energy, Jan. 31, 2013. Accessed June 11, 2014, at http://energy.gov/articles/record-year-american-wind-industry.

For Further Research

- National Center for Atmospheric Research researcher Bill Mahoney and University of Wyoming professor Jonathan Naughton describe advances in managing the power of wind. Learn more about their work: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QJwGMZN7Jig.

- Hermann, Eric. “Wind Energy: The End of the World’s Largest Windmill.” Mother Earth News, June/July 1996. Accessed June 27, 2014 at http://www.motherearthnews.com/renewable-energy/wind-energy-zmaz96jjzgoe.aspx#ixzz35sOzrsve. A feature article on Medicine Bow wind engineer Bill Young, who bought the Hamilton Standard turbine and operated it intermittently for several years.

- Click here for a video account of how Clayton Flint, despite his “bad reputation,” returned to Fort Bridger, Wyo., after time away and made a career in the wind-power business. Video produced as part of the Wyoming Voices Project by the University of Wyoming Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources and the Powder River Basin Resource Council.

Illustrations

- The Andrew Russell photo of the windmill, water tank and locomotive is from the collections of the Beinecke Library at Yale University, via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The ads from the Dec. 17 and Dec. 24, 1886 editions, respectively, of the Northwestern Livestock Journal are from the Wyoming State Library. Used with permission and thanks.

- The ad for the wind charger is from the DelmarDustpan blog. Used with thanks.

- The photos of the wooden windmill, the windmill with cattle and the Boeing MOD-3 turbine under construction near Medicine Bow are all from the Chuck Morrison collection at the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the completed USBR turbine is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The color photo of the wind turbines at Seven Mile Hill is courtesy of Pacficorp.