- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Thomas Jaggar’s 1893 Geological Survey of The A...

Thomas Jaggar’s 1893 Geological Survey of the Absaroka Mountains

Image

In the summer of 1893, the young geologist Thomas Jaggar took part in an extended expedition through the Absaroka Mountains to chronicle the rugged landscape of canyons and plateaus east of Yellowstone National Park. The leader of the trip was Arnold Hague, a distinguished geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who had been documenting the Yellowstone region since 1883.

In 1893, and again in 1897, Hague and Jaggar conducted geological surveys of the Yellowstone Park Timber Land Reserve, which later became the Shoshone National Forest. Their goal was to chronicle the geology of the Absarokas, note any mineral potential, and better understand the primordial forces that had shaped the mountains.

Jaggar was 22 years old and fresh out of college when he came to Wyoming in 1893. He kept journals throughout the expedition and field notes of his geological observations. He also took photographs of the mountains and geological features along their circuitous route.1 These photos are important historical artifacts and are among the best evidence modern researchers have that document the character of historical landscapes around the Absarokas and northwest Wyoming.

The Expedition Leaders

Thomas Jaggar is not a well-known entity in the geological world of Wyoming as he only spent two summers in the state with geologist Arnold Hague. After a few years working for the U.S. Geological Survey, and a stint as a geology professor at Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Jaggar ventured to Hawaii and spent most of his professional life studying the volcanic activity of the Hawaiian Islands. Jaggar was instrumental in the establishment of Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, serving as its first director starting in 1912. He also helped create Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park and served as the first Chief Volcanologist for the National Park Service beginning in 1926.2

When Jaggar first came out to Wyoming in 1893, he had just graduated with a bachelor’s degree in geology from Harvard. But he intended to continue his studies, and so getting field experience under a renowned leader in the profession was undoubtedly a beneficial prospect. Jaggar signed on as a volunteer assistant geologist. As such, he was not paid a salary for the three months he spent in Wyoming during the summer of 1893, but his travel expenses—food, train tickets, necessary gear—were covered by the U.S. Geological Survey.3

The leader of both the 1893 and 1897 surveys of the Absaroka Mountains was Arnold Hague. He had been surveying the geology of Yellowstone National Park for the U.S. Geological Survey since 1883. Hague had been through parts of the Absarokas before 1893, during his previous surveys of Yellowstone, but never made them a primary focus.

Hague had graduated from Yale in 1863, before continuing his studies in Germany, exploring geology in China, and examining the volcanoes of Guatemala and the Pacific Northwest. When Congress created the United States Geological Survey in 1879, Clarence King was made the department’s first Director. King and Hague had been friends and classmates at the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, so with his newfound position of authority, King appointed Hague as a principal geologist within the newly created government entity.4

Hague was initially assigned to explore the geology and mineral potential of the Great Basin region of Nevada and Utah.5 But in 1883, he was put in charge of the first geological survey of Yellowstone undertaken by the U.S.G.S., of which there would be many more. This notable appointment to such a geologically and culturally unique area served to ultimately cement Hague as one of the premier authorities on the Yellowstone region and its geology. As such he was afforded the opportunity to rub shoulders with other notable men who shared his interest in Yellowstone—men such as George Bird Grinnell and Theodore Roosevelt. Through these connections, Hague became increasingly active in the early conservation movement to protect Yellowstone. He was even an honorary member of the Boone & Crockett Club, despite not meeting the qualifications for regular membership as a qualified hunter.6

Lobbying Congress

Since the early 1880s General Philip Sheridan, George Bird Grinnell, Arnold Hague, and others had been lobbying sympathetic politicians in Washington, D.C. to expand the boundaries of Yellowstone to the east and south. Starting in 1883, Senator George Vest of Missouri introduced a succession of four bills aimed at extending the boundaries of the park. None of these pieces of legislation went anywhere—largely due to the opposition of railroad and mining interests. But anxieties about protecting forests and watersheds were an concurrent priority for many early American conservationists. In March 1891, congressmen and senators passed a bill that allowed the President to set aside forested lands as timber reserves. Although not the expansion of Yellowstone they had hoped to bring about, Hague and Grinnell advocated for a timber reserve with the exact borders they had suggested to Senator Vest in the 1880s. The proposition worked—the Yellowstone Park Timber Land Reserve was formed by proclamation of President Benjamin Harrison on March 30, 1891. It was the first of its kind, created to protect the remaining timber on the public domain and to ensure a regular flow of clean water from streams.7

Hague, Grinnell, and others saw the newly created reserve as the potential eastward extension of the park they had long tried to bring about. Again, Senator Vest tried for eight years to have the Yellowstone Timber Land Reserve added to Yellowstone National Park. His bill passed the Senate four times but always remained stuck in Congress. Eventually the matter was dropped entirely.8

Encompassing 1.2 million acres of extremely mountainous terrain, the Yellowstone Park Timber Land Reserve initially lacked any semblance of organization or coherent purpose. Indeed, government officials and Wyoming residents alike had little notion of what the new geographic entity was intended to accomplish.9 And the original legislation allowing for the designation of forest reservations did nothing to address the matter of their management. To remedy this lack of bureaucratic objective, the U.S.G.S. set out to account for the natural resources and human activity found within the new reserve. Hague, already the authority on the Yellowstone region, was the obvious person to oversee these official surveys.

Throughout the 1893 and 1897 surveys of the Absarokas, Hague assembled his observations and geological notes, along with those of Jaggar, to write the Absaroka Folio of the Geologic Atlas of the United States. This large document accounted for the geological features of the Yellowstone Park Timber Land Reserve and especially the mineral resources found therein. It also included detailed topographic maps of the Ishawooa and Crandall Quadrangles – the two survey areas they had been investigating during their expedition.10

The 1893 Expedition

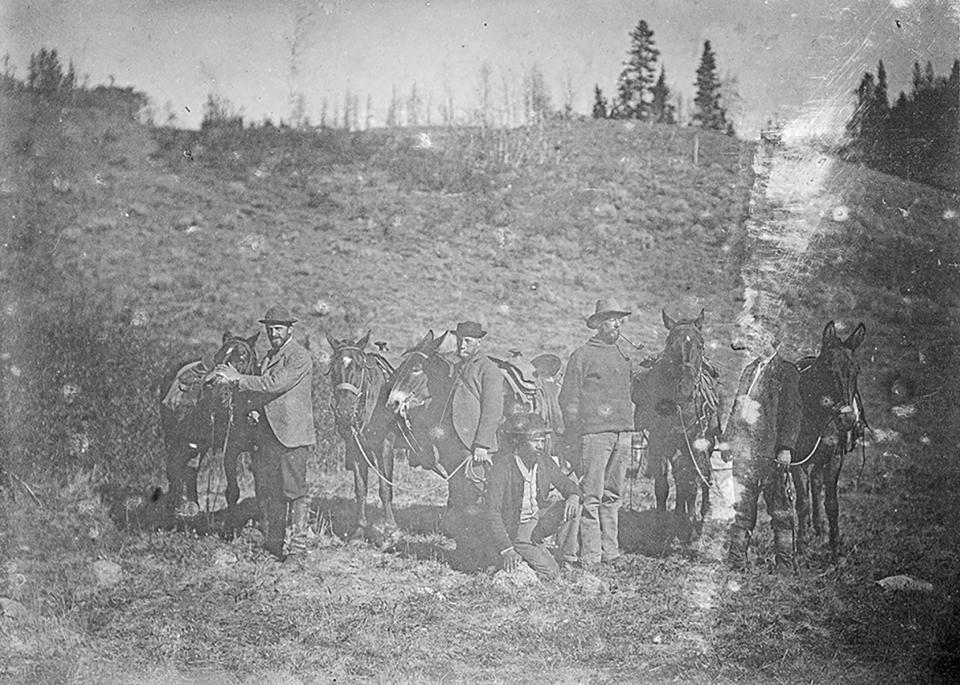

The 1893 expedition commenced when the members of the party convened in Bozeman, Montana, over the duration of a few weeks in early July. Thomas Jaggar departed from Boston on a westbound train on June 29. He stopped in Chicago for a few days preceding and including Independence Day, where he visited the World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, and bought photographic supplies. On July 5, he boarded another sleeper train for Bozeman, arriving at his destination on July 8.

Fred Koch, the head packer for the trip, had been in Bozeman for a few days assembling supplies. Koch had recently returned from Laramie, Wyoming, where he had secured horses and mules for multiple U.S.G.S. field surveys in the northern Rocky Mountains during the summer of 1893. John Condiff, the other packer, and John Anderson, the cook, were residents of the Bozeman area. The men set up a staging camp on the outskirts of town and spent a few days buying horses, securing necessary items, and drafting letters. A great deal of planning had to be done as the men were to be tramping through the Absarokas for the next three months.11

On July 15, the party finally set out to begin their work. Over the following week, the men rode east over Bozeman Pass to Livingston, up Boulder Creek, down Slough Creek to Lake Abundance, and over Daisy Pass to Cooke City. Near the isolated mining town, the men camped on lower Republic Creek—exploring the country for a few days and occasionally visiting the post office to send and receive mail.

Image

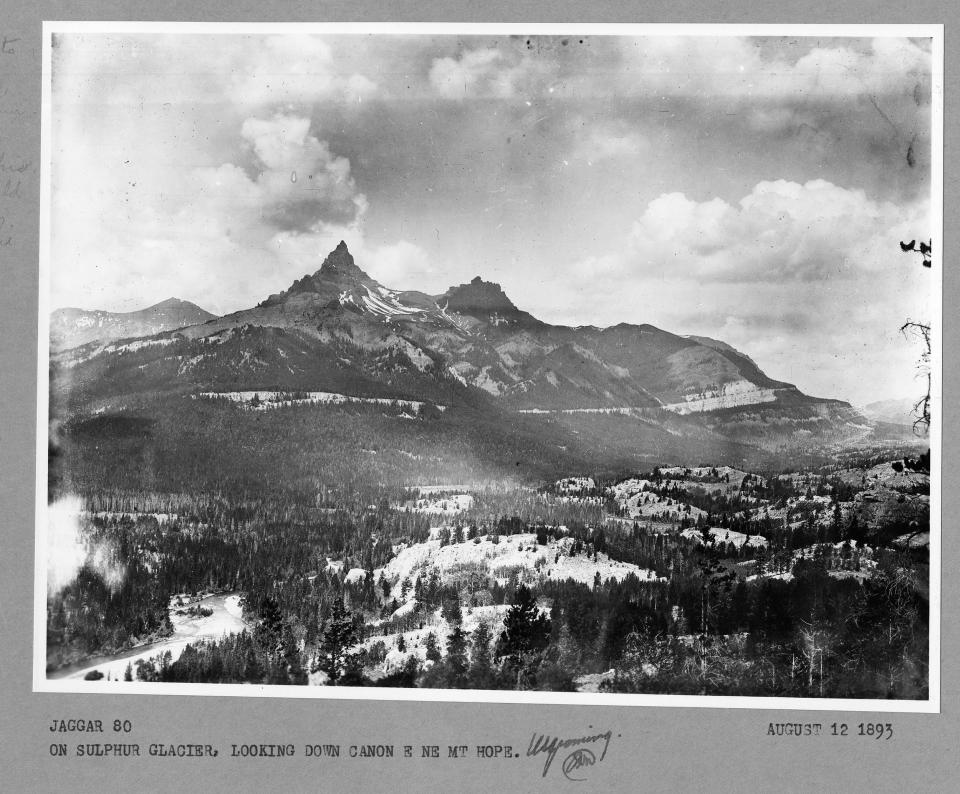

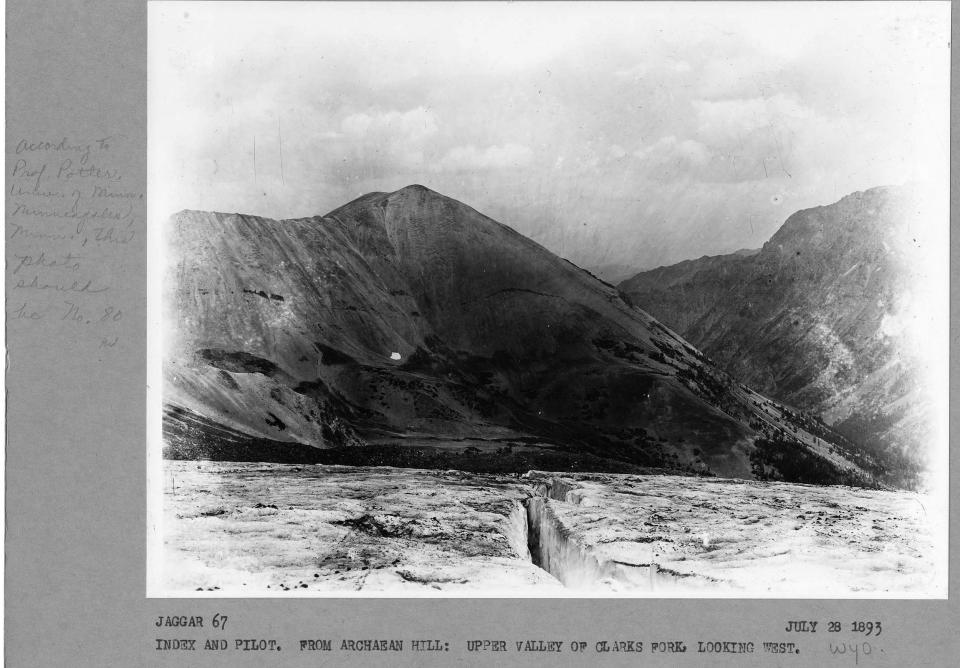

On July 27, the party broke their camp and traveled into the upper Clarks Fork Valley. Here their work surveying the geology of the Absarokas started in earnest. Their first camp was at the confluence of Pilot Creek. At this camp, they shot a deer for meat and Jaggar climbed up one of the rocky outcroppings on the north side of the Clarks Fork River to gain a proper view of the wide valley.

Two days’ travel out of Cooke City brought them to Crandall Creek, so named for the old prospector Jack Crandall who was purportedly killed in the vicinity in the early 1870s. Here they found a few small cattle ranches and associated log cabins. The party was able to travel easily in the upper Clarks Fork country because a road had been built from Billings, Montana, to the Cooke City mines in 1885. This wagon road traveled over Dead Indian Pass on the east and wound its way through the ledges and bogs in the Clarks Fork Valley all the way to Cooke City.12

On July 30, Jaggar and John Anderson climbed up a hill on the east side of Hunter Peak. Here Jaggar took a photo looking southeast across the valley floor. Jaggar’s journal entry reads: “John Anderson & I went up the mountain north of Crandall Creek: hard climb: John Anderson went up cliff where it was very dangerous…. loosening rocks & gun goes off in my face: not shot but shock.…. John Anderson & I found a well preserved large buffalo skull on the top mountain with horns.”13

Exploring the Sunlight Region

Image

The following day the party left the road and followed the old trail up Lodge Pole Creek and over the low divide into Sunlight Basin. Here they found three primitive ranches staggered across the valley every few miles, although the U.S.G.S. topographic map included with the 1899 Absaroka Folio indicated four structures. These included the ranches of Alpheus Beem at the mouth of what later became known as Beem Gulch, the Willard and Ella Ruscher homestead at the mouth of Trail Creek, Charlie Huff at the mouth of Huff Gulch, and the spread of Frank and Kitty Chatfield on the north side of Sunlight Creek below Little Bald Ridge.14 Jaggar and the survey party camped near the confluence of Little Sunlight Creek, below towering rim rocks of limestone. From the campsite, Hague and Jaggar explored the unique geology of Sunlight Basin.

Members of the party paid the Chatfields a visit on numerous occasions. As Jaggar noted in his journal: “Walked down to Chatfield’s Ranch and got a pail of milk from the old man. He gave us some points on deer; said their business was mostly cattle & dairy products. Good face: talked well: people in this country are mostly very intelligent.”15

In 1893 there was already a rough wagon road through the lower stretches of Sunlight Basin to the Chatfield’s ranch, but beyond that there was only a miner’s trail. On August 7, the men broke their camp at Little Sunlight Creek and headed up the trail to the mining area. They first camped near the mouth of Galena Creek, a “beautiful camp ground by mountain torrent; grassy among the pines.”16 From their centrally located camp along the upper section of Sunlight Creek, Hague and Jaggar explored the dike complexes and mineral prospecting in the surrounding mountains.

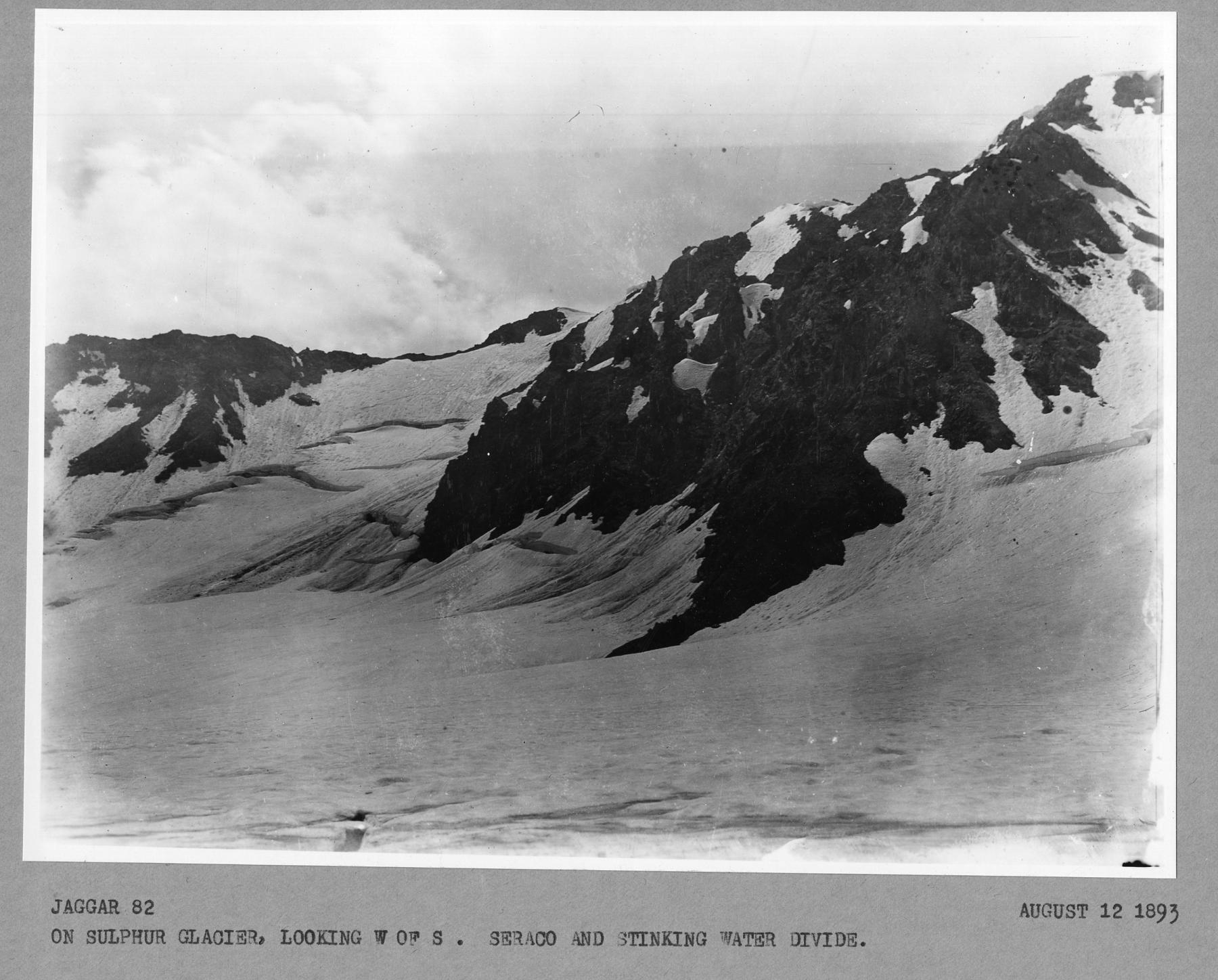

Image

On August 11, they again moved camp to Sulphur Creek, a main tributary of upper Sunlight Creek six miles downstream from the Galena Creek camp. Here they encountered the mining camp of Jack Baronette—a guy with a long history in the Yellowstone region since the days of the Montana gold rush.17 The following day, Jaggar, Hague, and Fred Koch went up on the glacier at the very head of Sulphur Creek. Jaggar took photos of the stream emerging from its base and atop the glacier itself. These latter views afforded spectacular views of the surrounding mountains and glacial remnants in the Sulphur Creek cirque.18

Image

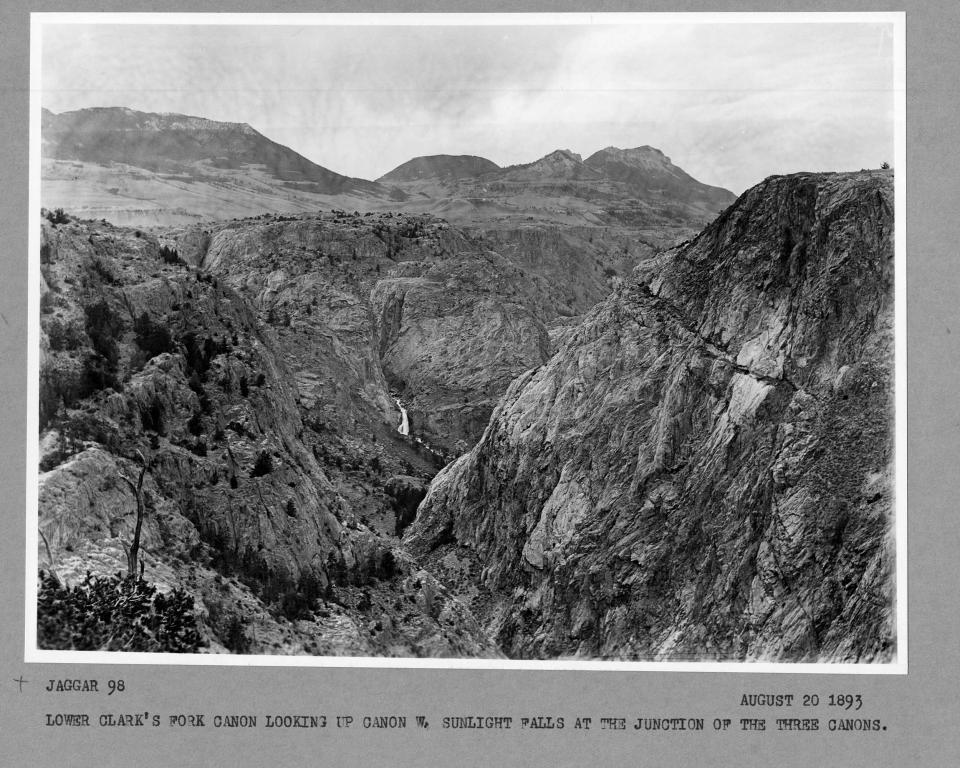

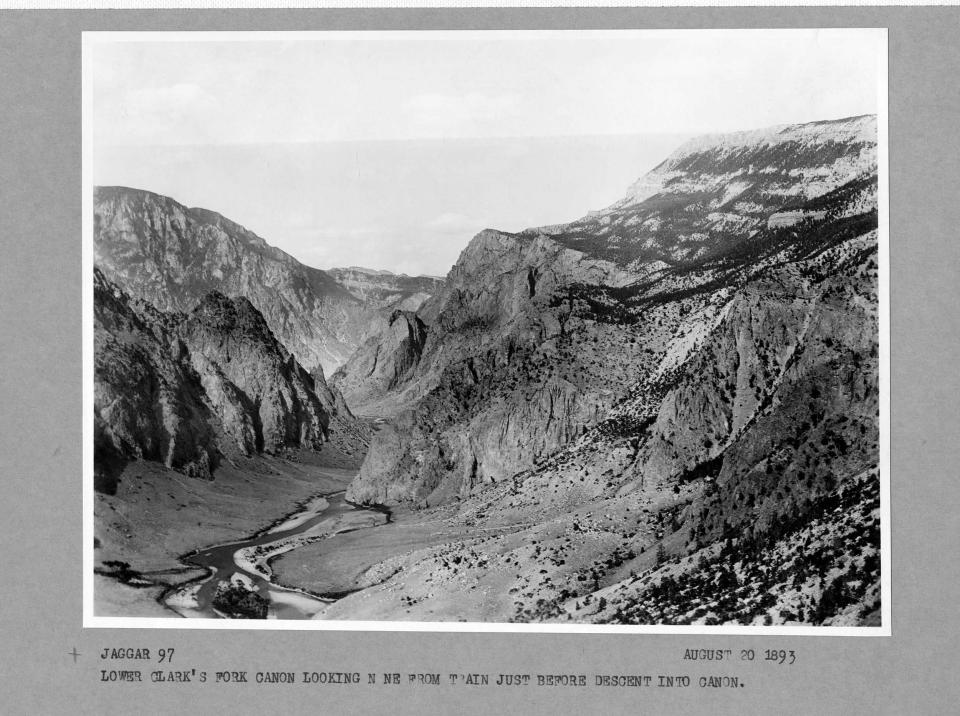

Having concluded their exploration of the upper Sunlight region, the party moved back down to Sunlight Basin and into the Clarks Fork Canyon. They camped in a natural pasture near Camp Creek—where today’s Highway 296 crosses the open benches between Sunlight Basin and Crandall Creek. In this area the geologists were interested in the faulting along the Clarks Fork Canyon, the prominent limestone terraces, and the abundant evidence of glaciation. On August 16, Hague, Jaggar, and John Condiff made the steep descent to the base of the canyon where Jaggar took four photographs.

Exploring the Canyons and Creeks

Image

The party then moved east along the Clarks Fork Canyon to a popular campsite along Dead Indian Creek. Their campsite was located at the base of the steep road descending from Dead Indian Hill to the east. The site had been a popular camping place for early white travelers and Native Americans alike. Jaggar noted in his journal the many good arrowheads found nearby and also a tourist party traveling by wagon to Yellowstone. From their camp along Dead Indian Creek, the men spent a few days exploring the narrow box canyons above and below. Jaggar noted some of the details of these surveys in his journals, writing on August 19: “Fred Koch, Mr. Hague & I rode 6-7 miles down Dead Indian and Clarks Fork Canon along trail, top of first limestone bench. Superb canon views: 3 canons, Dead Indian, Sunlight and Clarks Fork come together in a point. Lost trail: I tried to go down bed of stream into canon & failed. Afterward we found precipitous trail going down to a little island at foot of cliff. Sheep skulls & elk antlers everywhere.”19

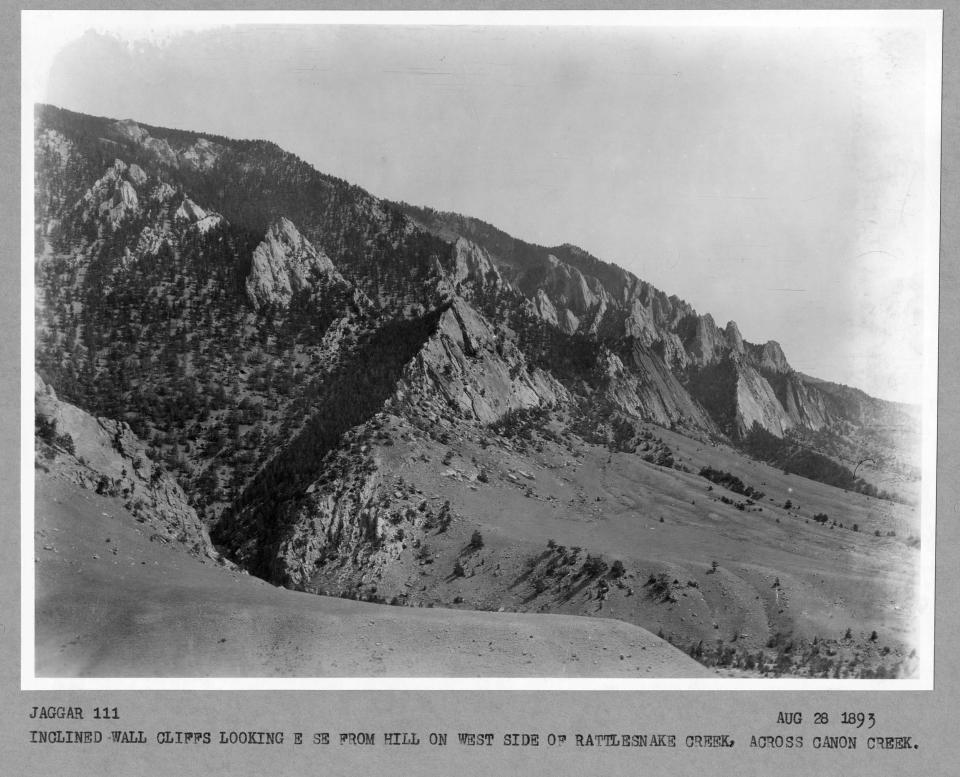

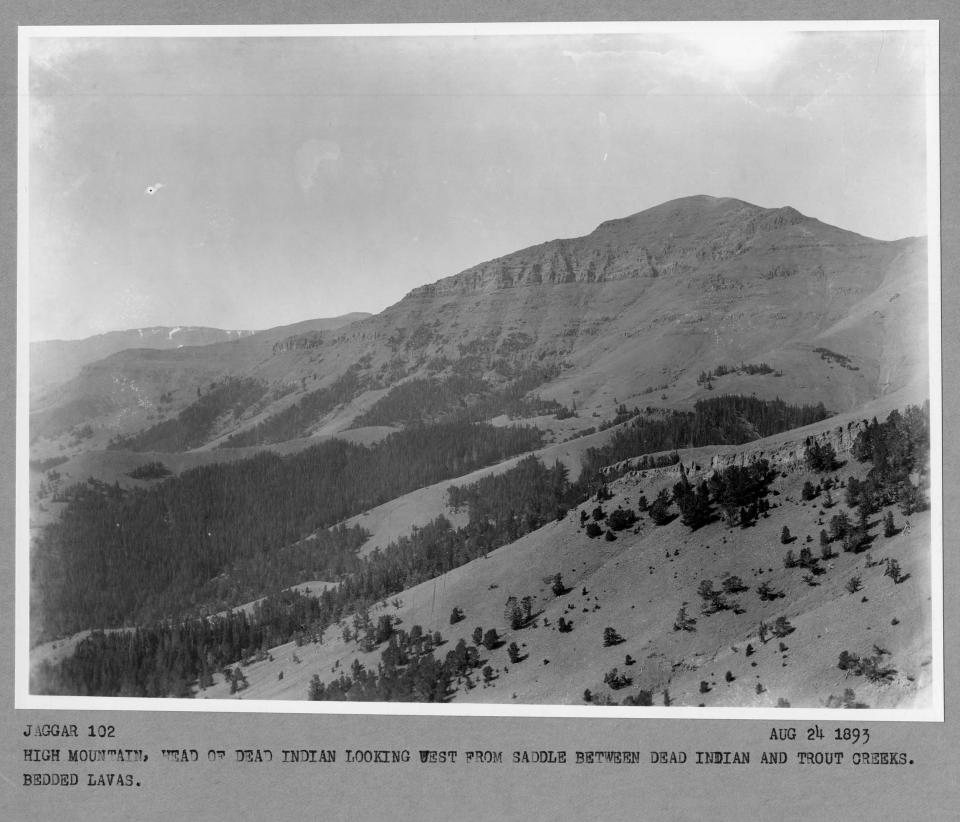

From their camp above the Clarks Fork Canyon, the party moved up Dead Indian Creek to its low saddle with Rattlesnake Creek. Along their route they passed through a camp with abundant evidence of bear hunting. As Jaggar noted in his journal: “Crossed stream at a camp where men had been bear hunting: 32 bear paws on the ground that they had left.”20 They made camp near a spring-fed stream in a grassy bottom on the edge of the pine forest. This area became known as Bear Springs and was for a long time a popular stopover spot for backcountry travelers.

Image

The following day, Jaggar climbed the ridgeline to the west. He took two photos near the head of Morning Creek and another atop Robbers Roost Peak—a hogback mountain that is the eastern spur of the slightly higher Trout Peak.

The party then moved down to Rattlesnake Creek and into the Stinking Water drainage, later renamed the Shoshone. Jaggar took a photo of the limestone palisades on the east side of Rattlesnake Canyon, as well as the isolated ranch cabin of Joseph Hunter, an old prospector based in Red Lodge, Montana, who eventually moved up to Alaska during the Yukon Gold Rush where he lost everything.21

Having traveled the entire length of Rattlesnake Creek from top to bottom, the party found itself near the scattered ranching community of Marquette where the North Fork and South Fork of the Stinking Water converged in a wide basin before flowing east through the narrow Stinking Water Canyon. Jaggar recounted in his journal: “Trotted down 5 miles to ford of North Fork Stinking Water. Arid plains, refreshing green cottonwoods, willows & rose & goose-berries bushes in stream cutting,” adding, “Next 5 miles across old lake bed. Level shore line benches & wide 10-12 miles lake bed. This great arid plain between forks of Stinking Water.” The area Jaggar was riding across would be inundated in 1910 after the completion of the Shoshone Dam, later renamed the Buffalo Bill Dam.

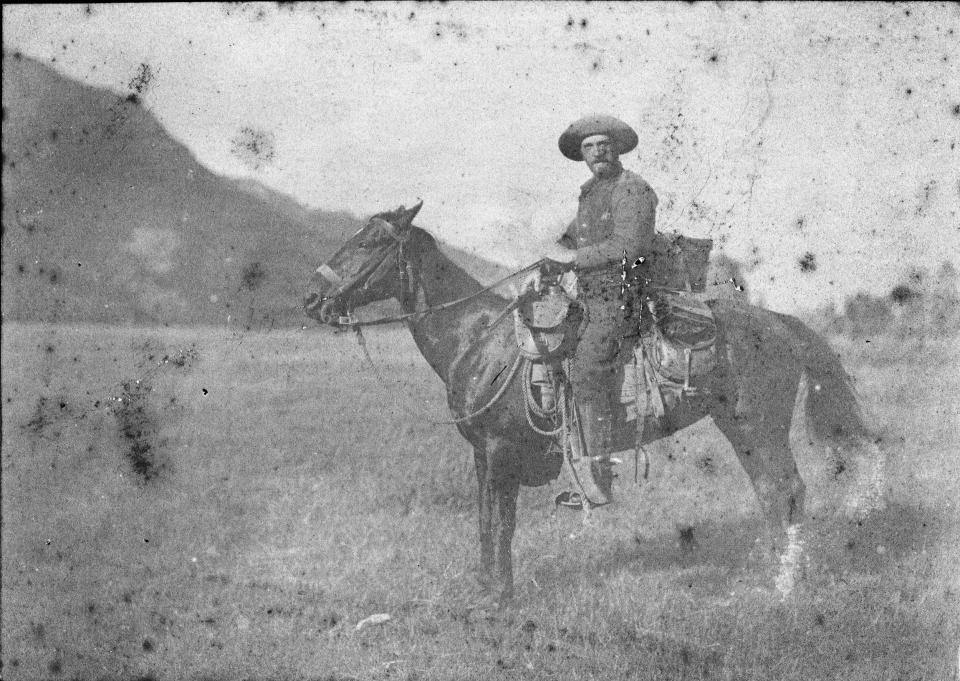

The party traveled up the South Fork of the Stinking Water to the Valley Home Ranch owned by Jim McLaughlin and his wife “Buckskin Jenny.”22 The McLaughlins had recently begun guiding visiting hunters and taking a few informal boarders to their Wyoming ranch every summer, so they were happy to accommodate the U.S.G.S. surveying crew.23 Moreover, Jim agreed to guide the party up the South Fork to the Continental Divide over the following few days.

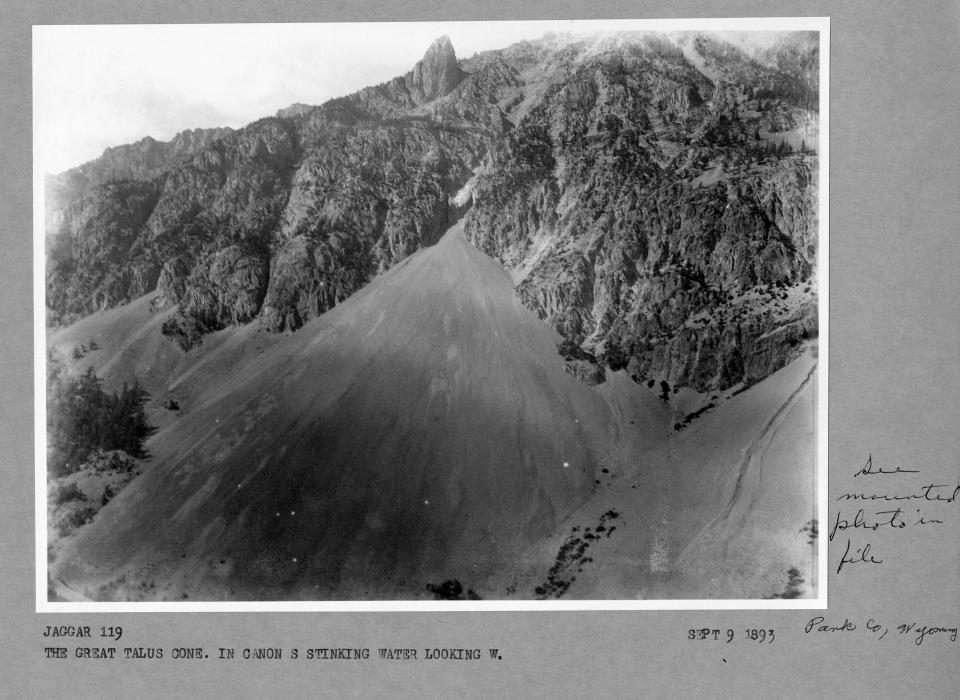

Image

On September 1, the party embarked up the South Fork of the Shoshone with Jim McLaughlin as their guide. Their trail took them on a narrow path above the South Fork Canyon, a route that had been recently cleared by local prospectors, but a perilous track nonetheless. Jaggar wrote of the journey up the South Fork: “Trail the most precipitous & dangerous we have been over canon cut deep in the lavas. Great talus cone. In one place trail cut with pick-axe through solid rock along vertical wall. Other places talus, very steep. Mules pitched ahead recklessly.”24 Ultimately the trail brought them into a relatively slender flat-bottomed valley where the little “Stinking Water Mining Region” was located. The operation only consisted of a few crude cabins in a grassy meadow south of Needle Creek.25 The mines on the South Fork would soon be purchased by William F. Cody and his business associates, but in the summer of 1893 they were still being marginally developed by a few resident prospectors.26

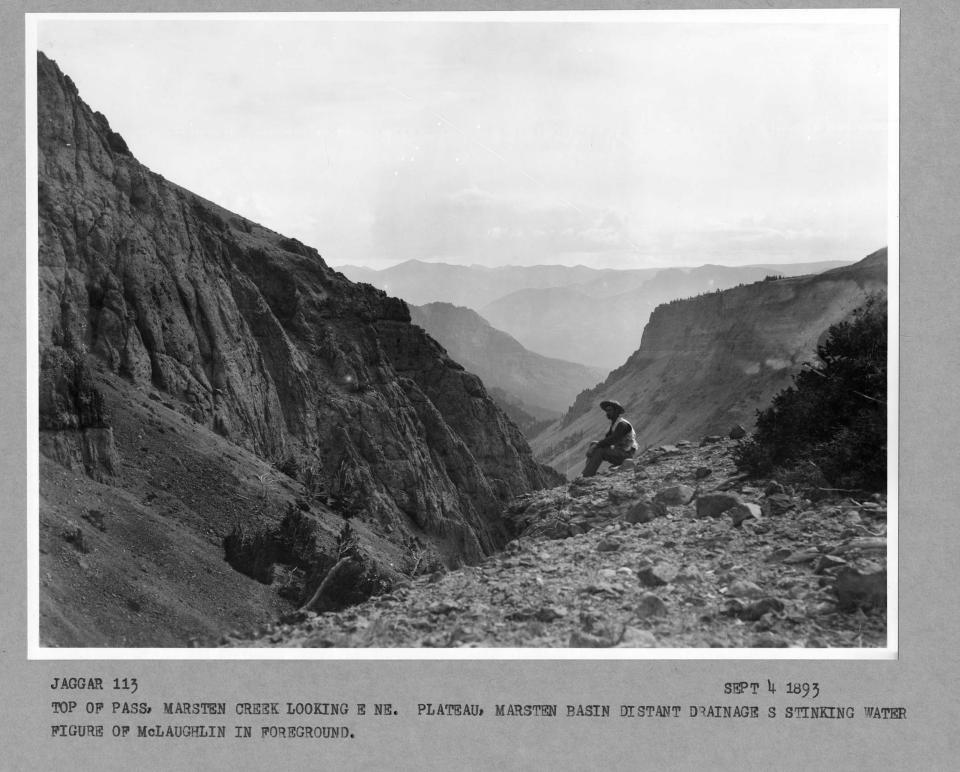

After a day spent inspecting the minerals at Needle Creek, the party continued up the South Fork, ascending Marston Creek to the wide meadow at its head just below the Continental Divide. “Marston Basin is a wide meadow surrounded by the bedded breccias in great walls 900 feet high & wooded lower slopes on north,” Jaggar wrote in his journal on September 3, noting, “The walls are section of great plateau that forms the continental divide.”27 The following morning, the party climbed to Marston Pass and the Continental Divide. From this vantage, the miles of alpine on the Buffalo Plateau were visible to the south and west. Jaggar took a few photos in the vicinity of Marston Pass—two near the old crest of the pass and a little lake near its outlet—another two from the continental divide ridge that separates Lost Creek and the Pacific drainage from the headwaters of the Yellowstone River and the Atlantic drainage.

On September 5, the party packed up their camp on the Continental Divide and backtracked down Marston Creek to the South Fork. After two days of exploring around the upper reaches of the South Fork and the minerology of the mining region at Needle Creek, the party again made camp at McLaughlin’s ranch. From this convenient and comfortable camp, Hague and Jaggar allocated five days to investigating the geological features of the South Fork valley. While on the South Fork, Jaggar encountered the U.S.G.S. parties of Philip Gallagher and Frank Tweedy. The Gallagher party was surveying the boundaries of the newly created Yellowstone Park Timber Land Forest Reserve, while Tweedy was documenting the topography of the region for inclusion in the same Absaroka Folio to which Arnold Hague was contributing geologic descriptions.

After keeping a comfortable camp on the McLaughlin Ranch, the party broke camp and struck off again, this time heading up Ishawooa Creek towards the Thorofare country. “Terrible trail. Steep & along dangerous precipices, superb canon & views each way fine,” Jaggar wrote of the trail up Ishawooa on September 13, “Worse [sic] trail we have been over & a memorable one… Camped in an open glade 17-18 miles up.”28 The following day they achieved the crest of Ishawooa Pass and descended into the broad Pass Creek. “Beautiful elk country, open river & glades in open passes—grassy,” Jaggar wrote of the country, noting the change from the rugged and narrow drainages on the east side of the divide.29

Making camp in a large meadow adjacent to the confluence of Pass Creek and the Thorofare, Hague and Jaggar traveled up to the head of Thorofare Creek the following day. Here they encountered an elk hunting camp with the likes of Sam Aldrich, Billy Hofer, Tazewell Woody, and a gentleman only referred to as Two Dog Jack, along with their dude hunters.30 Their presence in the remote country only serves to highlight the fact that even at this time, these inaccessible places were far from wildernesses devoid of human presence. While camped at the mouth of Pass Creek, John Anderson shot an elk, which Sam Aldrich helped them pack back to their camp from a narrow ravine high above. This gave the camp some much needed protein, as their supplies were running low and they had only two weeks left before their return to Bozeman..

Returning Home

The party moved down the Thorofare to Open Creek, its next large tributary. They followed its course for a few days, all the while Jaggar taking photos towards the eastern flanks of the Trident Plateau and along Petrified Ridge. On September 19, the party broke camp again with the intention of heading back to Bozeman and bringing their summer’s work to a close. They traveled down Thorofare Creek to its confluence with the Yellowstone River near Bridger Lake and Hawks Rest mountain, then turned north and entered Yellowstone National Park. Their trail took them along the east side of Yellowstone Lake and north into Hayden Valley along the Yellowstone River. “Saw 2 stages on road on opposite side [of the Yellowstone River], telephone wires, women walking: strange to see signs of civilization…Disgusting to come out of back woods to this tourist place,” Jaggar scribbled in his journal.31 While in the park, Hague introduced Jaggar to the geological wonders of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Norris Geyser Basin, and Mammoth Hot Springs. They followed the course of the Yellowstone River through Paradise Valley in Montana and back to Bozeman, arriving there on September 29 after 77 days in the saddle traipsing through the Absarokas and the Greater Yellowstone region.

Tired, sore, and eager to return to the comforts of home, Thomas Jaggar boarded an eastbound train at the Bozeman station on October 2. He arrived back in Boston five days later.

After earning a master’s degree and Ph.D. and studying in Germany at Munich and Heidelberg Universities, Jaggar returned to Wyoming in 1897 to complete the geological survey of the Absaroka Mountains under Arnold Hague. This later expedition allowed the geologists a final chance to compile the materials needed for the Absaroka Folio, published two years later in 1899.32

Footnotes

1. Jaggar’s journals, field notes, and photographs are in the collection of the U.S.G.S. Field Records Library at the Federal Center in Denver, Colorado.

2. Janet L. Babb, James P. Kauahikaua, and Robert I. Tilling, The Story of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory—A Remarkable First 100 Years of Tracking Eruptions and Earthquakes(Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, 2011), 3-9; John William Siddall, ed., Men of Hawaii:Being a Biographical Reference Library, Complete and Authentic, of the Men of Note and Substantial Achievement in the Hawaiian Islands, vol. 1 (Honolulu, HI: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1917), 151; Thomas Augustus Jaggar, Absaroka Mountains 1893 and 1897: Jaggar’s Diaries and Photographs, comp. Bruce Blevins (Powell, WY: WIM Marketing, 2002), 105-106.

3. Jaggar, Absaroka Mountains 1893 and 1897, 5.

4. “Arnold Hague,” International Who’s Who (New York: International Who’s Who Publishing Co., 1912), 558.

5. Richard A. Bartlett, Great Surveys of the American West (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1962), 149, 179-185.

6. “The Boone and Crockett Club,” Forest and Stream, March 8, 1888; Richard A. Bartlett, Yellowstone: A Wilderness Besieged (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1985), 142-142; Arnold Hague, Geological History of the Yellowstone National Park (Washington D.C.: National Park Service, 1920); Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell, American Big Game Hunting: The Book of the Boone and Crockett Club (New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Co., 1893).

7. Timothy Cocharone, Robert A. Murray, and Theodore J. Karamanski, Narrative History of the Shoshone National Forest, unpublished manuscript, Park County Archives Collection, Cody, WY, Shoshone National Forest File), 34-48; James B. Trefethen, Crusade for Wildlife: Highlights in Conservation Progress (New York: Boone and Crockett Club, 1961), 44-61.

8. Aubrey L. Haines, The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park, vol. 2 (Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press, 1977), 94-99.

9. “A Protest: On the Enlargement of the Yellowstone National Park,” Billings Weekly Gazette, October 25, 1888, page 6; “Voice of the People” Letter to Wyoming Governor F.E. Warren, Red Lodge Picket, September 5, 1891, page 4.

10. Arnold Hague, Absaroka Folio, Wyoming, Folios of the Geographic Atlas No. 52 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey, 1899).

11. Jaggar, Absaroka Mountains 1893 and 1897, 3-4.

12. “The Cooke City Road,” The Billings Gazette, May 14, 1885, 3, col. 1; “The New Road from Billings to Cooke,” The Billings Gazette, June 22, 1885, 4, col. 2.

13. Thomas Jaggar, field notebook entry, July 30, 1893, “Original Field Notebooks of 1893 and 1897,” File NO-7876, United States Geological Survey Field Records Library, Denver, Colorado.

14. The Chatfields, Huff, and Beem had originally been hunting and trapping for the market when they settled in Sunlight Basin, but in time they also participated in prospecting, ranching, and guiding visiting hunters.

15. Jaggar, field notebook entry, August 2, 1893.

16. Jaggar, August 7, 1893.

17. “Baronett’s Bridge,” Bozeman Weekly Chronicle, September 30, 1885, 3, col. 4; Aubrey L. Haines, The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park, vol.1 (Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press, 1977), 130-33, 144-146, 243, 263, 281; Haines, Yellowstone Story, vol.2, 442-443.

18. A fair amount of prospecting had been going on in the vicinity of Sunlight Peak and Stinkingwater Peak by the time Hague and Jaggar visited the area in 1893. John Painter and the Winona Mining Company would later expand these mining operations. “A Real Bonanza,” The Picket-Journal (Red Lodge, MT), August 20, 1892, 3, col. 5; “The Sunlight Basin,” The Picket-Journal, September 23, 1893, 3, col. 3; Brian Beauvais, “Hope and Hard Luck: A History of Prospecting and Mining in Wyoming’s Absaroka Mountains,” Annals of Wyoming 96, no.2 (Fall 2024): 35-40.

19. Jaggar, August 19, 1893.

20. Jaggar, August 23, 1893.

21. “Terse Town Talk,” The Picket-Journal, January 21, 1893, 1, col. 1 (mention of J.G. Hunter); “Early Cody Settler Suicides at Tacoma,” Northern Wyoming Herald (Cody, WY), June 6, 1917, 3, col. 4.

22. In 1915, the McLaughlins sold their Valley Home Ranch to Larry Larom and Winthrop Brooks, who changed its name to Valley Ranch and operated it as one of the country’s premier dude ranch resorts.

23. W. Hudson Kensel, Dude Ranching in Yellowstone Country: Larry Larom and Valley Ranch, 1915-1969 (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark Co., 2010), 22-26.

24. Jaggar, September 1, 1893.

25. “Local Brevities,” Red Lodge Picket, September 23, 1893, page 3.

26. “Stinking Water Mines,” Stinking Water Prospector (Red Lodge, MT), June 24, 1891, 1, col. 2; “The Elkhorn Camp,” The Picket-Journal, September 3, 1892, 3, col. 1; Robert E. Bonner, William F. Cody’s Wyoming Empire: The Buffalo Bill Nobody Knows (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), 162-164; George W.T. Beck, Beckoning Frontiers: The Memoir of a Wyoming Entrepreneur, ed. Lynn Houze and Jeremy Johnston (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 210; Beauvais, “Hope and Hard Luck,” 40-46.

27. Jaggar, September 3, 1893.

28. Jaggar, September 13, 1893.

29. Jaggar, September 14, 1893.

30. Sam Aldrich was an early homesteader and dude rancher on the South Fork—a neighbor of the McLaughlins, Elwood “Billy” Hofer was a well-known Yellowstone area personality who had served as Theodore Roosevelt’s guide in the Two Ocean Country along with his partner Tazewell Woody—a native Missourian who had ventured into the Rocky Mountains in the days of the Montana gold rush. Who Two Dog Jack was is anyone’s guess. Kensel, Dude Ranching in Yellowstone Country, 30; Theodore Roosevelt, “An Elk Hunt on Two Ocean Pass,” in The Wilderness Hunter: An Account of Big Game in the United States (New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1902), 177-202; Janet Chapple, ed., Through Early Yellowstone: Adventuring by Bicycle, Covered Wagon, Foot, Horseback, and Skis (Lake Forest Park, WA: Granite Peaks Publications, 2016), 60-62.

31. Jaggar, September 22, 1893.

32. Jaggar, Absaroka Mountains 1893 and 1897, 71, 103-105.