- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Stephen Leek, Father of The Elk

Stephen Leek, Father of the Elk

Stephen Nelson Leek (1858–1943), a founder of Jackson, Wyo., was an early wildlife photographer. His nationally recognized images of starving elk helped establish the National Elk Refuge near Jackson. As a hunting guide and dude rancher, his conservation advocacy came at a crucial time when the future of the species was in doubt. He was thus called “The Father of the Elk.”

In his times, Leek was intelligent, passionate and committed. Today, he’s an example of the difficulty of judging historical figures. The more scientists learn about ecology, the more concerned they become about Leek’s cause of artificially feeding elk in the winter. Leek was also a racial extremist, and in acting on those views participated in an event that even some of his contemporaries labeled “murder.”

The function of history is to report and to understand (not to participate in, cancel culture or conversely, to venerate). Who was Stephen Leek? What did he do, how and why? And what have been the effects of those actions? History provides facts to answer those questions, so that moral debates and judgments can be more informed, rational and useful.

Leadership

Leek was born in 1858 in Turkey Point, Ontario, Canada. In his youth he lived in Illinois, Nebraska, Utah and Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains. In 1888, at age 30, he homesteaded a ranch three miles south of today’s townsite of Jackson, in an area now known as South Park. One of his descendants later said, “He knew this was to be his home and took to his heart the beauty of the scenery and the wonder of the abundant wildlife.”

White people had only recently permanently settled the remote, high-elevation valley. Leek soon became a leader of the community, which then consisted of about 50 people scattered throughout Jackson Hole. Leek married Etta Wilson, niece of Elijah Nicholas Wilson, who soon founded the nearby town of Wilson. Leek recruited his half-brothers Hamilton and Charles Wort to join him in Jackson Hole; Charles’ sons later built the famed Wort Hotel in downtown Jackson.

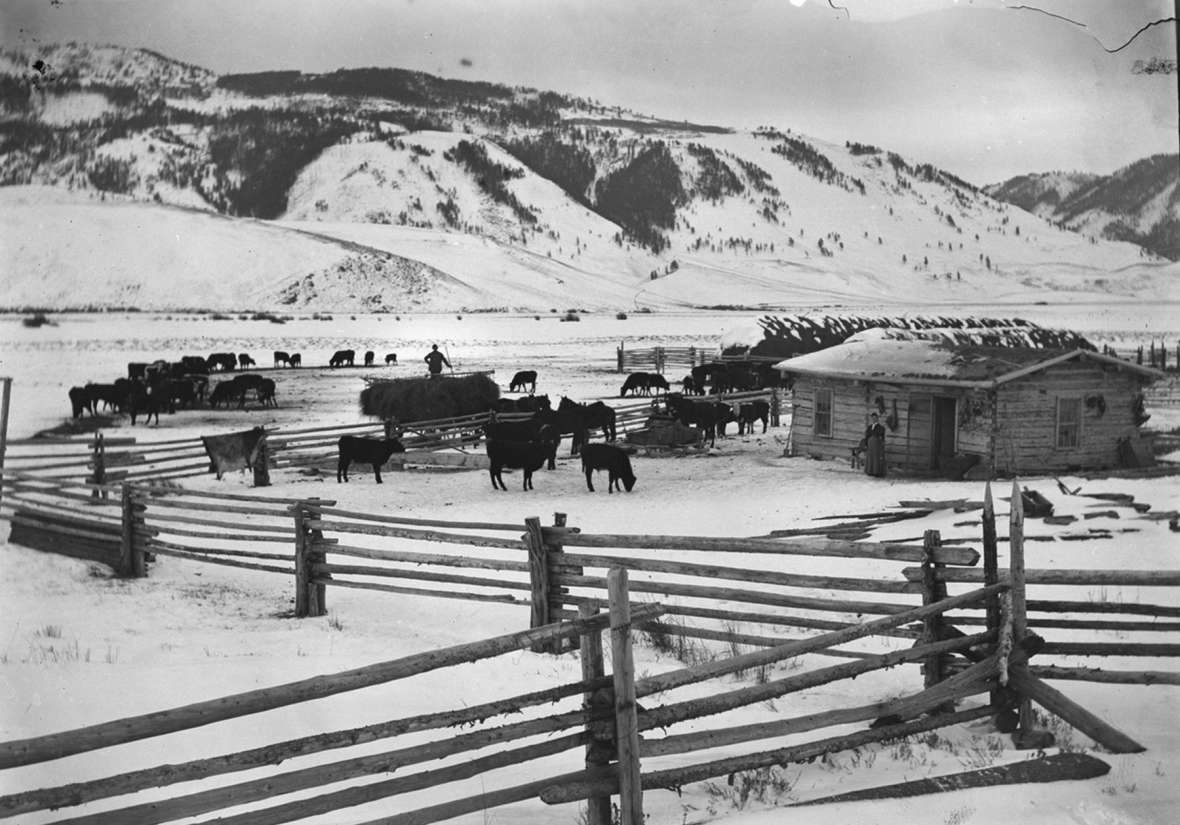

Leek established the valley’s first sawmill, a water-powered mill on Trail Creek, in 1893. He had the materials shipped 120 miles from the nearest railroad station, at Market Lake (now Roberts), Idaho). Leek was the first area resident to irrigate his ranch and plant grain. By 1895, his ranch boasted one of the biggest barns in the county, capable of holding 50 head of livestock and 200 tons of hay. In 1907 he served as a state representative. In 1919 he arranged to show the valley’s first movies.

Like many in the area, Leek’s jobs and hobbies were tied to wildlife and the outdoors. When he arrived, he was a trapper. Later he raised cattle, hunted and guided other hunters. In 1889, he established a “clubhouse” on Leigh Lake, in today’s Grand Teton National Park, where he hosted hunters from out of town—making him one of the area’s first outfitters. As guiding and outfitting gradually evolved into the industry of dude ranching, Leek is one of several people sometimes called Jackson Hole’s first dude rancher.

In the late 1800s, Leek built a hunting and fishing camp at a particularly scenic spot on the shores of Jackson Lake, north of Colter Bay. In 1927, Leek designed and built a rustic lodge of native logs and stone at the site. (At the time, the land was owned by the U.S. Forest Service, which gave him a lease.) He and his sons Holly and Lester ran a summer boys camp and hosted hunters in the fall.

Although a chimney is all that remains of the lodge after a 1998 fire, the chimney—which was the most dramatic feature of the lodge’s main room—is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The adjacent boat launch, with private boat services and a lakefront pizzeria, are still operated by the National Park Service as Leeks Marina.

Early elk losses

When Leek arrived in Jackson, in 1888, area elk populations were at a high point. By some estimates, the area herd had reached 50,000, following several mild winters. Leek later wrote that he commonly saw tens of thousands of elk leaving Jackson Hole for the Green River Basin in the fall.

There is some scientific debate about whether elk that summered in the high country around Jackson Hole traditionally wintered in the Hole itself. Lower elevations in the Green River Basin and Red Desert would have been warmer and less snow-covered. Before the 1870s, many elk must have migrated there, although some may have wintered in Jackson Hole. But White settlements gradually disrupted migration patterns. Then the harsh winter of 1889–1890 killed as many as 20,000 elk.

Jackson residents were concerned. With agriculture difficult in the high-elevation valley, many hunted game for food all year long. Several, including Leek, were also making a living guiding hunters. Loss of elk threatened both their lifestyles and their livelihoods. Leek in particular was aware that wildlife populations could be decimated quite quickly. In his youth he’d seen Midwestern skies blackened by passenger pigeons, and the Nebraska plains blanketed with bison. By the time he arrived in Jackson Hole, the entire continent held just over a thousand buffalo and maybe a few thousand passenger pigeons.

Although he had once been an individualistic trapper, a latter-day mountain man, Leek came to see that saving wildlife would require laws and enforcement to limit the activities of hunters and trappers. Thus he became what we today might call a conservationist.

His first targets were roaming bands of indigenous people. Bannock and Shoshone had hunted in Jackson Hole for centuries—and those hunting rights were guaranteed in the tribes’ treaty with the federal government. But Leek and other leaders targeted them for arrest. One such attempted arrest, in 1895, led to a “war.”

In that war, Leek joined a posse that killed two Bannocks, an infant and an unarmed, nearly blind elderly man. Although the 1890s were in general a more racist era, even the U.S. Attorney for Wyoming called the deaths “murder.” In memoirs that Leek wrote in the 1930s, he referred to the dead elderly Indian as a “good Indian.” He expected people to be so familiar with the saying “The only good Indian is a dead Indian” that he could allude to it without explanation. He also accused (almost surely incorrectly) the Black “buffalo soldiers” sent to protect the Whites of Jackson Hole of thievery.

Jackson settlers won the war, which also led to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1896 Race Horse decision ending all Indians’ treaty-reserved rights to hunt off-reservation. But Wyoming elk populations continued to decline. Blame shifted to wolves, mountain lions and other predators. But Leek also criticized “tuskers.”

Ethics

The 1890s saw a fad for wearing elk teeth as jewelry. It may have begun with Elks lodges (officially, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks), whose members considered an elk tooth on their watch chains a status symbol. To fill this demand—teeth could run as much as $100 a pair—hunters flooded northwest Wyoming. They were called “tuskers.”

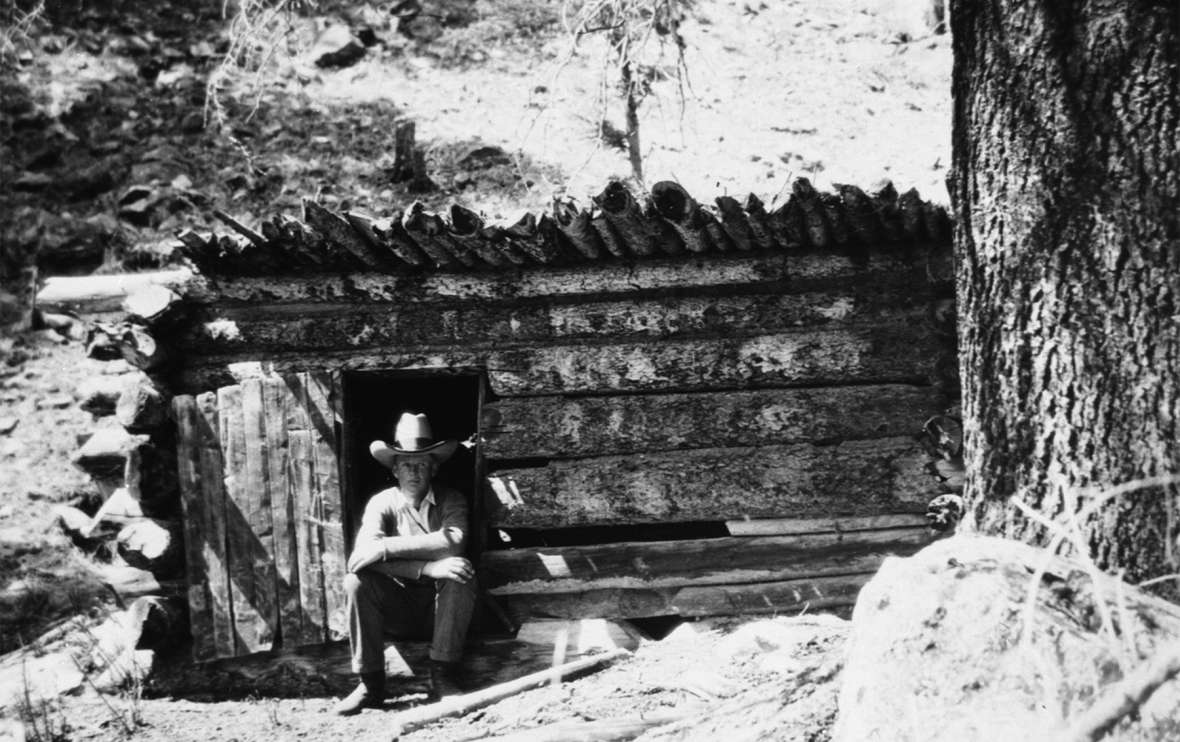

The tuskers ignored game laws; they were poaching. They built remote cabins on public lands, often hiding the structures in heavy timber or beneath overhanging ledges. Some tuskers used the cabins to smoke meat into jerky, which they could sell. However, Jackson residents accused the tuskers of wanton slaughter of elk solely for the teeth, leaving the meat to waste. One gang of tuskers was said to have killed 1,600 elk. Another was accused of driving elk into snowdrifts, where they became immobilized, and taking their ivories without bothering to kill them. One source said that tuskers massacred and left to rot more elk in a single winter “than were killed in ten years of normal hunting.”

As with the Indians, it’s possible that Jackson residents were condemning outsiders for practices that they condoned among themselves and their clients. For example, when a 1901 party of eight hunters with two guides killed 59 elk, did they use that meat, or waste it? The following year, William L. Simpson, then living in Lander, noted that he had seen elk teeth trafficked at Jackson Lake in the presence of a deputy game warden. In 1902, local rancher Harvey H. Glidden wrote that "elk teeth are the coin of the realm, all over Jackson's Valley and vicinity, for the purchase of supplies of all kinds, particularly whiskey."

Leek could see parallels to earlier wildlife tragedies such as bison being slaughtered for their tongues. Elk, like bison, had once populated the plains, and were now hard to find outside of greater Yellowstone. Were they, too, headed for near-extinction? Jackson’s guides and outfitters organized an association to help game wardens enforce Wyoming’s anti-poaching laws. In so doing, they helped bring law enforcement to this once-lawless country, because the cause of conservation demanded it.

In 1905-06, residents of Jackson organized vigilante parties to target the tuskers. Leek is not named as an organizer, but he probably participated. In 1906 he was elected to his single term in the state legislature, and helped pass a law that made it a felony to kill big game for tusks, antlers or heads. In 1907, the Wyoming legislature, surely again propelled by Leek, asked members of Elks lodges to denounce the wearing of elk teeth—although they were six years behind President Theodore Roosevelt, who with other conservationists began publicizing the issue in 1901. Although some Elks lodge members expressed skepticism that the elks’ peril was related to tusking, the lodges nevertheless discouraged the practice and encouraged other steps to preserve their elegant wild namesake.

The tuskers gradually faded away. But the elk were still in trouble.

Preserves and bad winters

In 1905, Wyoming created its first game reserve. To protect elk, the Teton State Game Preserve banned hunting and grazing in an area from Yellowstone Park’s southern border south to the Buffalo Fork river (which joins the Snake at today’s Moran, Wyo.), and from the continental divide west to the Idaho border (its boundaries were later adjusted). But this land, already regulated as a National Forest, was largely summer range. The elks’ problems came in the winter.

For example, in March 1907, 200 elk became snowbound on Willow Creek, near Pinedale, Wyo. The Teton National Forest supervisor collected contributions to provide hay to feed them. In 1909, the state set aside $5,000 for such feeding. That year at least 20,000 elk wintered in Jackson Hole (some estimates suggested 50,000). The elk population may have become inflated because of the settlers’ success at killing wolves and other predators. But now the settlers had to feed the elk to prevent starvation—up to seven pounds of hay per elk per day. In several winters, those efforts required private funding before the state appropriation became available.

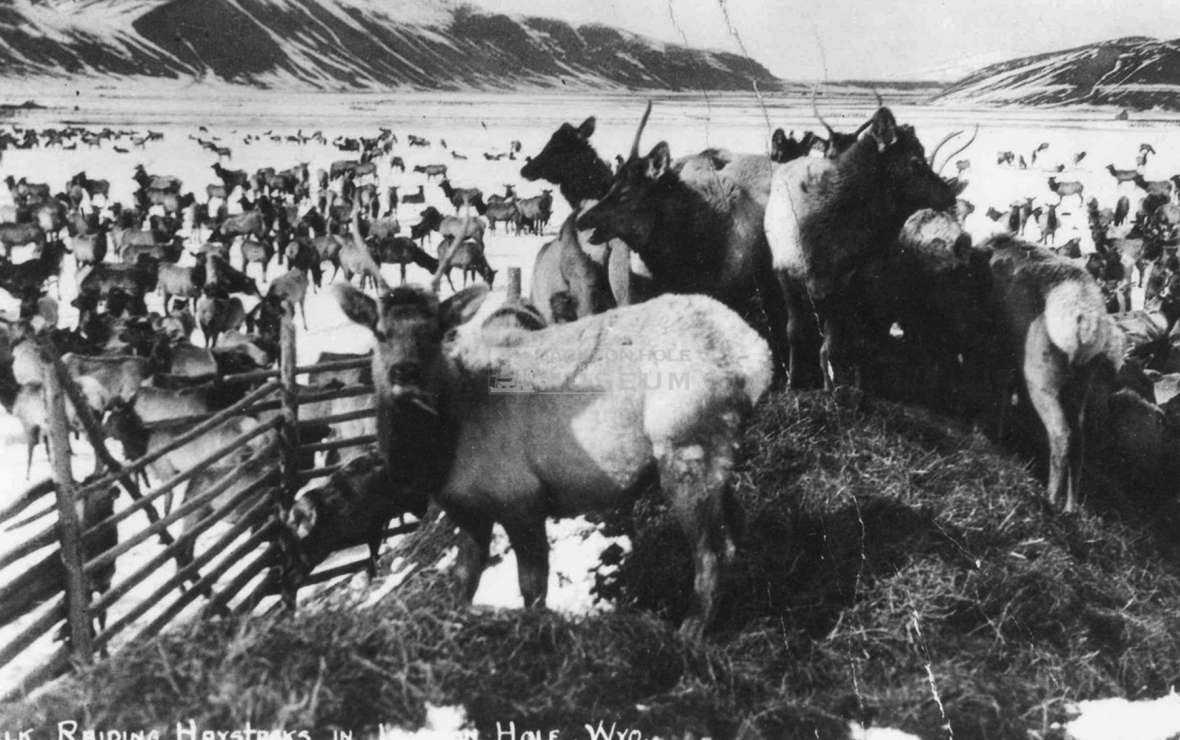

In their hunger, elk would raid ranchers’ haystacks. “When their feed is cut off by heavy snow, the elk swarm over the ranches by the thousands, tear down fences and devour the ranchman's stock feed,” wrote the Sheridan Daily Enterprise on March 9, 1910. Some ranchers would sleep, armed, in their haystacks to keep the elk away. However, many of them understood the economic importance of elk. Jackson residents appointed a committee of Leek, James M. Simpson and L.B. Hoagland to develop a permanent organization to feed and protect elk.

Then the winter of 1908–1909 proved especially severe. Several thousand elk died. Area sentiment settled on the need for some sort of winter refuge. In 1906, state game warden D.C. Nowlin had suggested setting aside a winter refuge in the Gros Ventre valley, east of Jackson. In 1909, the Wyoming state legislature asked Congress to give the state six 36-square-mile townships of Gros Ventre valley land for an elk refuge. But the proposal would have displaced homesteading ranchers, and public opposition killed it.

Photography

George Eastman (1854–1932) was the inventor of roll film and founder of the pioneering photography company Eastman Kodak in Rochester, N.Y. In 1905 he vacationed in Wyoming. Although neither man recorded the date, it was probably on this trip that Eastman met Leek and gave him a camera.

Legend suggests that with this gift, Leek suddenly discovered his talent for the new art of photography. That’s probably exaggerated: photos attributed to Leek date back as far as 1891, and an account in the Feb. 8, 1904, Wyoming Tribune noted that his elk photos would be featured in an upcoming state pamphlet. But Eastman’s device was certainly easy to use, and the connection also may have helped Leek acquire a Pathé motion-picture camera in 1907.

Through these painful winters, Leek photographed the starving elk thronged around Jackson. He would dress in white and paint his camera white to sneak up on elk in the snow. He took large-format glass-plate photographs of starving and dead elk. In 1908, he also took movies of elk, including scenes of them being fed from a hay wagon.

Leek used his photos to illustrate articles that he wrote for Outdoor Life, In the Open and many other publications. He assembled photos in a small illustrated book that he published under various titles, most often The Elk of Jackson’s Hole, Wyoming: Their History, Home, and Habits.

Most important, he went on tour. In 1909–10, on a vaudeville circuit of Orpheum theaters throughout the West, he showed lantern slides and movie footage of starving elk. The elk he showed resembled pets, domesticated but with personality. His pictures showed “graphically the needless suffering and death among these noble animals,” one reporter wrote. Publicity for the lectures billed Leek as “The Father of the Elk.” His efforts built sympathy across the nation for the plight of the Jackson Hole elk.

A national elk refuge

Meanwhile, sympathies within Jackson Hole also started turning. Support shifted to the idea of having the federal government buy out local ranches to establish a wildlife refuge. Hay could be grown on the property all summer, and fed to the elk in the winter.

On Aug. 10, 1912, Congress appropriated $50,000 for three purposes: to purchase 1,760 acres in the Flat Creek area north of Jackson, to set aside an adjacent 1,000 acres of public land and to purchase additional hay. At this point, elk occupied only 10 percent of their original winter range. By feeding these elk through the winter, the Biological Survey (predecessor of today’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) could ensure that elk didn’t go extinct, while also separating them from haystacks and people.

The refuge proved successful. It added adjacent ranchlands to eventually reach 24,000 acres. The Jackson elk herd remains one of the largest in the country, and a tourist attraction. For many decades, elk from Jackson and Yellowstone were shipped to 37 states plus Canada and Mexico, to reestablish elk herds across their former range. Biologist Olaus Murie studied Jackson’s elk for 18 years, leading to landmark advances in ecological science.

The refuge is also notable in political history, because Jackson Hole residents supported federal government ownership of land for conservation. Although in coming decades many of these same people would resist the creation of Grand Teton National Park, that effort was arguably more about preservation than conservation.

Should elk be fed?

Beginning with state appropriations in 1909, people have fed Jackson Hole elk all but 10 winters since. (Early exceptions included 1915 and 1926; more recently, 2018.) The feeding traditionally took place from January through March, when deep snows covered Jackson Hole. Under a plan adopted in 2019, feeding activities will slow considerably, with the volume of alfalfa-based pellets distributed each winter cut in half, and eliminated entirely during average winters.

Ecological science has demonstrated problems with feeding, hence this change. For example, the free food accelerated the decline of traditional migration routes. Soon after establishment of the Refuge, elk that summered in the nearby high country completely ceased winter migrations to the Green River valley and Red Desert. Area elk started wintering exclusively in Jackson, and concentrated their foraging near the feedgrounds.

Concentrating elk populations can lead to disease. Most other Western states have abandoned winter feeding programs. Amid concerns about chronic wasting disease—an untreatable, easily spread, always fatal malady that destroys the brain and central nervous system of animals in the deer/elk family—environmental groups have sued the National Elk Refuge and the U.S. Forest Service for moving too slowly in discontinuing feeding.

Although the federal feeding practices are better known, the state of Wyoming runs 22 additional feedgrounds across Teton, Sublette and Lincoln counties. These facilities help elk live through difficult winters. However, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department sees today’s elk populations as too high. Among other issues, overpopulations of elk out-compete mule deer, upsetting natural balances.

Artificial sources of winter forage disrupt the complex natural processes called ecosystems. For example, wolves are attracted to elk feedgrounds; elk respond by moving unpredictably. Sometimes vast numbers of elk move across the geographic boundaries set by Game and Fish, complicating the allocation of hunting permits.

Elk that winter on the National Elk Refuge can now be classified in two populations: “Suburban elk” have thrived by summering on private ranches and subdivisions in the southern part of Jackson Hole, while elk to the north have struggled, probably due to comparatively higher predation from Yellowstone-area wolves and grizzlies that avoid settled, “suburban” areas.

On the other hand, closing feedgrounds would be painful. It could mean fewer Wyoming elk to hunt and more conflicts with livestock. Most important, it could mean that Wyoming residents would have to watch thousands of elk die during each difficult winter—precisely the problem Stephen Leek so effectively demonstrated.

Leek’s legacy

After establishment of the Refuge, Leek continued to tour with his images. He continued to speak on behalf of the elk, and of Jackson Hole. His reputation grew. In 1920, an article by William T. Hornaday in Scribner’s magazine on “Masterpieces of Wild Animal Photography” said, “Mr. Leek has made so many stunning elk pictures that it is difficult to choose the masterpiece.” The 1920s were a heyday of dude ranching, and Leek lived in comfort. He spent the rest of his life as a community and industry leader.

Leek’s view of wildlife was very much in tune with his times. Like the writer-illustrator Ernest Thompson Seton, he built sympathy for animals by making them seem accessible, cuddly, almost human. Like the pioneer photographer William Henry Jackson, he used the new medium to make the wonders of Wyoming feel real, even for people who had never visited. Like the artist Charlie Russell, he used visual imagery to capture the tragedy of animal starvation in a difficult winter. Leek both built sympathy for wildlife and helped translate that sympathy into a sense that humans had obligations to those creatures. Because of his work, the National Elk Refuge could be seen as (in the words of one commemorative video), “our gift to this majestic species.”

That courage and vision should not be underemphasized. Leek helped lead one of the biggest humanitarian efforts of his day. At the time, it was easy for people to shrug off the potential extinction of species like elk and bison, as a small price to pay for progress. Leek’s efforts helped change those philosophies.

Yet in part because of Leek’s accomplishments, we now have different views of wildlife. We highlight their wildness, not their tameness; their difference from humanity, rather than their pet-like accessibility. We know much more about how they survive in the wild, and we have much more respect for those natural processes. These new values put us at odds with the consequences of Leek’s actions.

So do our values of racial justice. Leek’s racist words and actions are impossible to excuse. It’s hard to imagine how he could see a wild animal as so noble and deserving of sympathy, while denying such nobility and sympathy to large numbers of human beings simply because of the color of their skin. The best we can say is that Stephen Leek, like many of us, was a complex mixture of heroic and reprehensible traits. How we judge him says as much about ourselves as it says about history.

Resources

Primary sources

- “Against Elk's Tooth Charms.” Los Angeles Herald, Vol. XXIX, No. 78, 18 December 1901, accessed Sept. 14, 2020 at https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19011218.2.127&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------1.

- The Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y. online collections include photos from George Eastman’s Wyoming trips as well as some photos by Leek, at https://collections.eastman.org/people/36884/-/objects/list.

- Leek, Stephen N. “Chapters from the Eventful History of Jackson’s Hole.” 1939 typescript. Other Leek materials include a letter about elk, accessed Nov. 10, 2020 at https://jacksonholehistory.org/2002-0114-016/. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum, Jackson, Wyo.

- “Profusely illustrated,” Wyoming Tribune, Feb. 8, 1904, page 3, accessed Nov. 10, 2020 at https://pluto.wyo.gov/awweb/main.jsp?flag=browse&smd=1&awdid=7.

- “Ranchers organize to feed wild elk during winter,” Daily Enterprise, March 9, 1910, accessed Nov. 10, 2020 at https://pluto.wyo.gov/awweb/main.jsp?flag=browse&smd=1&awdid=1.

- Stephen Leek Collection. American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyo. Typewritten manuscripts as well as Leek’s photographs, many of which are online at https://digitalcollections.uwyo.edu/luna/servlet/uwydbuwy~74~74.

- Wyoming Newspapers. http://newspapers.wyo.gov. This resource has several articles about Leek, and others about elk. Search for “S. N. Leek” and other names or phrases.

Secondary sources

- Anderson, Chester C. The Elk of Jackson Hole: A Review of Jackson Hole Elk Studies. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Wyoming Game & Fish Commission, 1958.

- Betts, Robert B. Along the Ramparts of the Tetons: The Saga of Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Boulder, Colo.: Colorado Associated University Press, 1978.

- Brown, Roland W., Jr., ed. A Souvenir History of Jackson Hole. Salt Lake City: 1924, accessed Sept. 16, 2020 at https://archive.org/stream/jacksonholehist/jacksonholehist_djvu.txt.

- Burkes, Glen R. “History of Teton County (Part I).” Annals of Wyoming 44, no. 1 (Spring 1972): 73-106.

- Cole, Eric & Foley, Aaron & Smith, Bruce & Dewey, Sarah & Brimeyer, Douglas & Fairbanks, W. & Sawyer, Hall & Cross, Paul. (2015). “Changing Migratory Patterns in the Jackson Elk Herd.” Journal of Wildlife Management. 79, 877-886. 10.1002/jwmg.917, accessed Sept. 16, 2020 at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280134699_Changing_Migratory_Patterns_in_the_Jackson_Elk_Herd. Cole, a National Elk Refuge biologist, has published several other scientific studies.

- Commission on the Conservation of the Jackson Hole Elk. The Conservation of the Elk of Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Washington, D.C.: National Conference on Outdoor Recreation, 1927, accessed Sept. 16, 2020 at https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/157096.

- Cromley, Christina M. “Historical Elk Migrations Around Jackson Hole, Wyoming.” Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, accessed Aug. 26, 2020 at https://www.emwh.org/issues/brucellosis/WY%20ID/Historical%20Elk%20Migrations%20Around%20Jackson%20Hole%20%20Wyoming.pdf.

- Daugherty, John, et al. “Conservationists.” In A Place Called Jackson Hole: A Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park. Moose, Wyo.: Grand Teton Natural History Association, 1999, accessed Sept. 14, 2020 at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/grte2/hrs17.htm

- Dean, Ron, Ph.D. Feeding Big Game in Western Wyoming: A Tiger by the Tail. Ron Dean, 2016.

- Hornaday, William T. “Masterpieces of Wild Animal Photography.” Scribner’s Magazine, July 1920. Vol. LXVIII, no. 1, 11-31, accessed Sept. 16, 2020 at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Scribner_s_Magazine/qwIwAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Stephen+Leek+elk&pg=PA22&printsec=frontcover.

- Horowitz, Ellen. “Rocky Mountain Ivory.” Montana Outdoors. September-October 2012, accessed Sept. 14, 2020 at http://fwp.mt.gov/mtoutdoors/HTML/articles/2012/ivories.htm.

- Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. “National Elk Refuge and Stephen Leek.” Oct. 24, 2012 video, accessed Sept. 14, 2020 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pdVsq3h2A88.

- Koshmrl, Mike. “National Elk Refuge poised to change century-long feeding practices.” Jackson Hole Daily, Oct. 28, 2019, accessed Sept. 15, 2020 at https://www.jhnewsandguide.com/jackson_hole_daily/local/national-elk-refuge-poised-to-change-century-long-feeding-practices/article_a12cf579-4ad4-5a8b-b2a1-59226ce9c528.html.

- ____________. “Wave train of feedground litigation rolls on.” Jackson Hole Daily, April 27, 2020, accessed Sept. 15, 2020 at https://www.jhnewsandguide.com/jackson_hole_daily/local/wave-train-of-feedground-litigation-rolls-on/article_76bf628e-fcb8-596e-9e53-eaf56930f6a4.html.

- Mitman, Gregg. Reel Nature: America's Romance with Wildlife on Film. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Morriss, Steve. “National Elk Refuge: 1912 – 2012: Grass Roots Conservation.” Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum, accessed Sept. 16, 2020 at https://jacksonholehistory.org/national-elk-refuge-1912-2012/.

- Smith, Bruce. Where Elk Roam: Conservation and Biopolitics of Our National Elk Herd. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2012.

- Spadt, Zach. “Lawsuit Challenges Feeding Elk in Bridger-Teton National Forest.” K2 Radio, April 21, 2020, accessed Sept. 15, 2020 at https://k2radio.com/lawsuit-challenges-feeding-elk-in-bridger-teton-national-forest/.

- Thuermer, Angus M., Jr. “‘Decade of the elk’ for hunters as herds top goals by 32%.” WyoFile, Sept. 15, 2020, accessed Sept. 15, 2020 at https://www.wyofile.com/decade-of-the-elk-for-hunters-as-herds-top-goals-by-32/.

- ___________________. “Elk populations booming ahead of hunting season.” WyoFile, Sept. 11, 2018, accessed Sept. 15, 2020 at https://www.wyofile.com/elk-populations-booming-ahead-of-hunting-season/.

- U.S. Forest Service. “Early Fur Trappers,” accessed Sept. 15, 2020 at https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/btnf/learning/history-culture/?cid=fsbdev3_063669.

- Wyoming Game and Fish Department. “Stephen Leek: Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2015,” accessed Sept. 14, 2020 at https://wgfd.wyo.gov/Get-Involved/Outdoor-Hall-of-Fame/Stephen-Leek. See also the video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lhh3jJ3VFGU.

- Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. National Register of Historic Places. “Leek’s Lodge,” accessed Sept. 16, 2020 at https://wyoshpo.wyo.gov/index.php/programs/national-register/wyoming-listings/view-full-list/867-leek-s-lodge. The original nomination form contains much hagiographic material on Leek.

- ____________________________________. National Register of Historic Places. “Wort Hotel,” accessed Sept. 16, 2020 at https://wyoshpo.wyo.gov/index.php/programs/national-register/wyoming-listings/view-full-list/890-wort-hotel.

Illustrations

- The photos of Leek’s ranch and sawmill, the photo of Leek in the elk herd and the photo of Leek photographing elk are from the American Heritage Center. Used with permission and thanks. We assume that Leek took most or all of the photos that he is not featured in.

- The photos of the elk raiding the haystack and of the tusker’s cabin are from the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of Leek’s lodge and of him in his reading chair are from the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Used with permission and thanks.