- Home

- Encyclopedia

- National Parks, Science and The 1963 Leopold Re...

National Parks, Science and the 1963 Leopold Report

Zoologist A. Starker Leopold (1913–1983) was a widely admired professor at the University of California, Berkeley, author of several scientific books and leading member of a nationally prominent conservation family. But his greatest contributions came when he was presented with a Wyoming-based problem—and produced a solution far bigger and more useful than anyone had expected.

Image

Too many elk

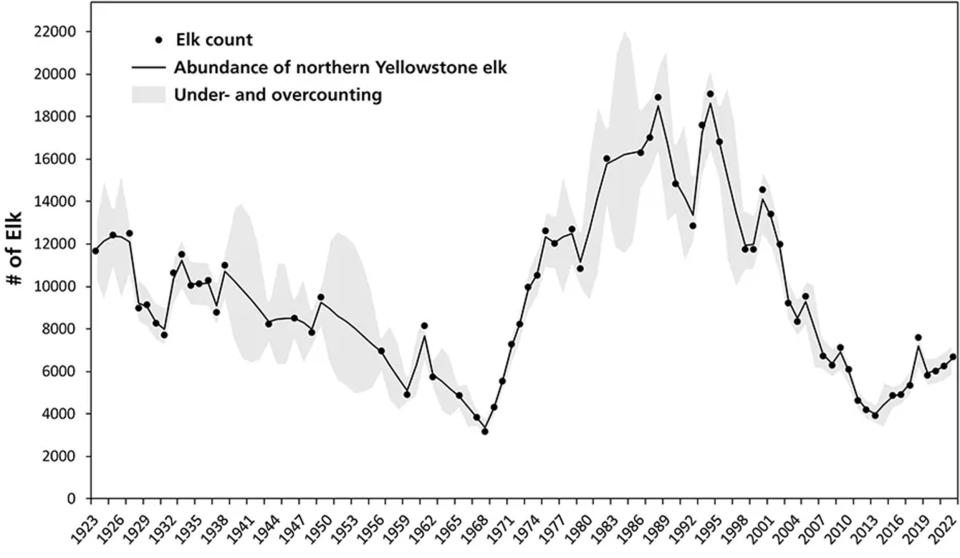

Although the story of 19th century Wyoming was one of dwindling wildlife populations, the situation reversed in the 20th century, through actions involving laws, the swaying of public sentiment, and ugly scapegoating. This was especially true inside Yellowstone National Park: Hunting was prohibited, Indigenous people banished and predators exterminated. In response—though few at the time fully grasped the ecological complexities—elk populations rose. Sometimes, even, too high.

Population explosions of elk and deer, known as irruptions, were surprisingly common around the West. Irruptions on the Kaibab Plateau north of the Grand Canyon in the 1910s, and in New Mexico’s Gila Wilderness in the 1920s, influenced the thinking of famed conservationist Aldo Leopold (1887–1948). He saw that irruptions led to overgrazing. That degraded the quality of the land, often permanently. Such habitat destruction harmed many forms of wildlife.

Beginning in 1913, Yellowstone tried addressing its elk surplus by trapping them for export. Today, most elk in the United States are descended from Yellowstone exiles. But as elk populations elsewhere became self-sustaining, demand for Yellowstone’s exports declined. Furthermore, the takings had never been sizable enough to slow Yellowstone’s irruption.

Image

During harsh winters in 1916–17 and 1919–20, rangers tried artificially feeding elk with hay. But this only facilitated the irruption. In 1934, rangers started killing elk. The park kept statistics: Over the next 27 years, 5,765 elk were transplanted elsewhere, 8,825 shot by rangers, and 40,745 shot by hunters outside park boundaries. Yet by 1961 the herd still numbered 10,000. The range was deteriorating—because, scientists at Montana State University said, it could support only 5,000 elk.

Attention focused primarily on the Northern Range—the drainages of the Lamar and Yellowstone rivers in the northern portion of the park. Many animals in this herd historically migrated down the Yellowstone River in the fall, to winter in lower elevations outside the park boundary in Montana. As those lands became developed, and hunted, elk learned to instead stay inside the park.

But inside the park, the high numbers of elk ate aspen saplings faster than the aspen could regenerate. They ate willows and bushes down to the nub. They stripped the bark off mature trees. They even ate normally unpalatable conifer boughs and sagebrush. The result hurt other animals. For example, elk out-competed beaver for aspen and willows. Fewer beaver meant fewer dams, which meant fewer wetlands, which meant fewer willows for animals to eat, a vicious cycle. The results rippled out from there—birds declined, weeds came in, topsoil washed away. This all threatened the natural conditions that defined the wondrous Yellowstone ecosystem.

Yellowstone superintendent plans to kill elk

In 1961, Yellowstone superintendent Lon Garrison embraced a bold plan: On a single cold December day, rangers would kill up to 5,000 elk. In a military-style operation, helicopters hazed herds of elk toward a line of men with high-powered rifles. The plan was as humane as possible: The elk were immediately butchered by members of the Blackfeet tribe; the meat was donated to their reservation and other needy causes. But the operation’s scale—rangers ended up shooting a total of 4,309 elk through the winter—made for a hideous scene.

“We’d just mow them down until they were all dead,” one ranger recalled. “That was just plain slaughter… I’ve never aimed a rifle at anything since. It was just too much.”

Hunters and outfitters were particularly enraged. In Cody, Wyoming, three hunting guides filed a lawsuit to try to stop the reductions. To an ethical hunter, respect for the animal stood in stark opposition to this industrial carnage. Hunting was a regulated activity that aimed at maintaining sustainable wildlife populations. Yet hunting was prohibited in Yellowstone. If the Park Service wanted to kill elk—a job that rangers found distasteful—why not reach out to hunters?

In Sports Afield magazine, conservationist Arthur Carhart noted that the problem was nationwide, and structural. National parks hadn’t been designed as wildlife refuges. They were set aside as scenic spots, which ended up being useful for wildlife because most parks outlawed hunting. But their boundaries hadn’t been drawn around ecosystems. Irruptions of elk or deer were hard to address because they crossed boundaries, creating problems for other federal agencies, state game departments and private landowners.

An ecological solution might involve reintroducing predators such as wolves. But most experts of the time believed that was impractical. For one thing, Carhart said, “not allowing the park camper to carry a gun inside the park, could raise the question of whether these areas are set aside for people or for animals.”

Many fans of national parks opposed opening them to hunting. Many of the protesting hunters were actually hunting guides, who would make money off hunting inside the park—so should it also be opened to grazing and other moneymaking ventures? To the contrary, advocates felt, providing sanctuary to all forms of nature was the best path to preserving unimpaired natural conditions in national parks.

Caught in a crossfire, in April 1962 Interior Secretary Stewart Udall did what great politicians always do. He called for a review from an independent blue-ribbon commission. To chair the Advisory Board on Wildlife Management, he turned to one of the nation’s leading experts on irruptions, ecosystems and hunting.

Starker Leopold’s expertise

Starker Leopold was Aldo Leopold’s oldest son. (His full name was Aldo Starker Leopold; Starker was his paternal grandmother’s maiden name.) Like his siblings Luna, Carl, Estella and Nina, Starker aspired to not only tend his father’s amazing legacy, but also build on it. His father, trained as a forester, had practically created the discipline of wildlife management. Starker got a Ph.D. in zoology to better ground that discipline in pure science.

Starker used his science and discipline on behalf of animals. He wrote comprehensive books about wildlife in Alaska and Mexico (where his study took advantage of the Spanish he learned from his mother, a descendant of Hispano New Mexicans). He recommended policies to address deer irruptions north of Yosemite National Park. While teaching at Berkeley, he joined the boards of the Sierra Club, Nature Conservancy, Wilderness Society, National Wildlife Federation and California Academy of Sciences. He was interested in using science to make good wildlife policy, and he would help anyone—university, nonprofit or government—who shared that goal.

Leopold was also an avid hunter. He enjoyed showing people wolf teeth-marks on the butt stock of his father’s old rifle. He once wrote a magazine article that quoted the poet and hunter Archibald Rutledge: “I would not say anything against hiking, but it is as much like hunting and fishing as a mother-in-law’s kiss is like a bride’s.”

As a scientist, Leopold continually called for game managers to make more animals available to hunters, usually by improving habitat. As a scientist, Leopold also killed a lot of wildlife for specimens. A colleague on one of his Mexico trips recalled, “We just shot everything that was loose in there.” Leopold did not see these actions as hypocritical: He believed that regardless of how many animals any individual hunter killed, the key to thriving wildlife populations was habitat—a healthy ecosystem. Like his father and many other giants of conservation history, he believed that hunters collectively could be harnessed to improve those ecosystems.

Leopold was thus a fascinating choice to head this commission. Nobody could dispute his scientific credentials. Yet hunters could hope that as one of them, he would call for a landmark change in policy: to allow hunting in Yellowstone.

Image

Leopold’s innovation

Leopold wrote the report himself, with consent but little participation from the rest of the commission. “I really worked long and hard on that,” he later recalled. “I got in a lot of the ideas that had been brewing in my mind for a long time.”

Udall had asked the commission to recommend the best way to control elk populations. But, Leopold realized, that was a discussion of management methods. Before you could evaluate a method, you had to know something about the goals and policies it was designed to implement. What were the goals of wildlife management in the national parks? And what policies would best achieve those goals?

Such surprisingly simple questions had surprisingly insufficient answers. Park Service values had been established by the 1916 Organic Act, which sought “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." The law restated a tension also expressed in the 1872 law establishing Yellowstone: between preserving “natural conditions” and having them provide “enjoyment” to people.

The laws were commendable in identifying this tension. But they didn’t provide much help to resolve it. Park Service founder Stephen T. Mather was a millionaire businessman who donated his time and fortune to the cause; his able assistant Horace M. Albright (later the first civilian superintendent of Yellowstone) was at the time a mere law student. Their lack of land management experience created a gap. How was an administrator supposed to act in choosing between preservation and enjoyment? If, say, a proposed hotel would degrade wildlife habitat, what guidelines could help a park superintendent weigh those values? For decades, the only way to answer those questions was to speculate: What would Mather do?

Leopold now suggested a primary goal for park management: that the plants and animals (he referred more technically to “biotic associations”) “be maintained, or where necessary recreated, as nearly as possible in the condition that prevailed when the area was first visited by the white man.” Those original conditions had entranced people enough to set these places aside as parks. But since then, they’d been too vastly manipulated.

For example, Leopold wrote, “A visitor entering Grand Teton National Park from the south drives across Antelope Flats. But there are no antelope. No one seems to be asking the question—why aren't there?” Whether regulating animal populations or encouraging mature open forests, the report said, parks should manage their landscapes toward a goal: “A national park should represent a vignette of primitive America.”

New perspectives

To achieve this goal, the report boldly recommended a policy of management. Amid the complexity of ecological issues, you couldn’t just leave things alone. Furthermore, Leopold continued, that management should involve native species. “Restoration of antelope in Jackson Hole, for example, should be done by managing native forage plants, not by planting crested wheat grass or plots of irrigated alfalfa.”

Such management required research. Rather than merely allowing scientists from universities or other agencies to conduct research in parks to meet their own goals, the report said, the Park Service should pay for its own science based on its own needs. “Most of the research now conducted by the National Park Service is oriented largely to interpretive functions rather than to management,” the report noted. By contrast, for management purposes, the Park Service should encourage more research along the lines of the ecological studies that had identified the Yellowstone elk problem.

Leopold arranged to present the report to Interior Secretary Udall in front of the 1,100 attendees of the 28th North American Wildlife Conference, in Detroit in 1963. But after Udall saw a draft of the report, somehow a conflict emerged in his schedule and he sent an underling instead.

Leopold later claimed that Udall skipped the conference because he was afraid of controversy surrounding the report’s new perspectives on fire. “Of the various methods of manipulating vegetation, the controlled use of fire is the most ‘natural’ and much the cheapest and easiest to apply,” the report said. Most people—even most scientists—then believed that fire was dangerous, or even evil. Leopold was proposing that in some cases it might be good.el

Contrary to Udall’s fears, the report’s new perspectives were well received. (Controversy around Yellowstone fires would not ignite until 25 years later.) Indeed, Leopold remembered Udall apologizing for skipping the report’s unveiling: “Starker, God damn you, you hit a home run, and I didn’t know it!”

Image

Management and hunting

After outlining his philosophy, Leopold’s report returned to the question he’d been asked. The best way to manage animal populations to meet the levels they had at first contact, he said, was through natural predation. “The effort to protect large predators in and around the parks should be greatly intensified,” although that would probably not be enough to sufficiently reduce elk herds. Trapping and transplanting elk were also justifiable, but again not sufficient. Special late hunts to capture migrating herds outside park boundaries worked well, despite the dangers of causing changes in migration habits, but they too might not be enough. Thus, finally, “Where other methods of control are inapplicable or impractical, excess park ungulates must be removed by killing.”

How to do the killing? This was a question of the methods that would best accomplish management goals: “Every phase of management itself [must] be under the full jurisdiction of biologically trained personnel of the Park Service.” Whether it was manipulating habitat or reducing Yellowstone elk, any park management effort was “part of an overall scheme to preserve or restore a natural biotic scene. The purpose is single-minded.” State regulators did not share that singlemindedness: They had other goals. Recreational hunters had other goals.

“A limited number of expert riflemen, properly equipped and working under centralized direction, can selectively cull a herd with a minimum of disturbance to the surviving animals or to the environment,” the report said. By contrast, recreational hunters were a bad option. “General public hunting by comparison is often non-selective and grossly disturbing.” (Leopold clearly favored rangers for the task of killing elk, although the report held out the possibility that it could be done by private hunters hired under stringent criteria.)

Hunters, outfitters and state hunting regulators had to accept Leopold’s conclusions. After all, nobody could dispute his credentials. And the report exhibited the sort of clear thinking and eloquent presentation that Leopold’s father had made famous.

The report’s drawbacks

Although the report was well received, and its message consistent with contemporaneous scientific reports, its short-term policy impact was mixed. Some park managers misinterpreted it, or mis-characterized their actions as fulfilling the report’s philosophies. And some wondered how scientific managers, or the academics at Montana State, could be so sure of the numbers produced by their models.

Continued public outrage over rangers killing Yellowstone elk caused the Park Service in 1967 to simply stop addressing the elk irruption. To satisfy political demands, managers decided that regardless of what the ecological models said, the optimal elk population must be whatever the real-world population was. They wouldn’t manipulate it. Thus by the 1980s, elk populations had doubled from the levels that had prompted Garrison’s 1961 plan. The range condition, which by some accounts had failed to improve from 1962–67, was further degrading. Only after the reintroduction of wolves in 1995 did elk populations begin to decline.

What’s more, the idea that scientists should manipulate nature—which for Leopold was beyond doubt—proved difficult for many people to accept. For example, The Living Wilderness, the quarterly magazine of The Wilderness Society, gave the Leopold Report big and mostly positive play in its spring-summer 1963 issue. But in an editorial, Howard Zahniser objected to Leopold’s focus on management. People’s attitude toward nature, Zahniser felt, should be “to let natural forces operate within the wilderness untrammeled by man… With regard to areas of wilderness we should be guardians not gardeners.”

Zahniser had authored, and was then lobbying for, what would become the 1964 Wilderness Act. Its “guardian” view, that wilderness should be protected and left alone, would prove far more popular than Leopold’s “gardener” view, that wilderness should be managed. Zahniser’s hands-off approach dominated wilderness philosophy for decades—although today, climate change is posing new threats to unmanaged natural conditions.

Some public resistance to the Leopold Report arose from its own misinterpretation of ecological principles. Leopold basically suggested freezing ecological processes in time. He later admitted that “stopping the clock” was wrong. Instead, he acknowledged, nature consists of “dynamic processes that don't stop” and he should have recommended that parks retain “natural biological and geologic processes” in order to “perpetuate the ecosystem as first observed by the white man.”

Sadly, Leopold never seemed to realize that even this formulation was still inappropriate. It embraced a duality of white-men-versus-nature, and implied that places like Yellowstone were a Garden of Eden ruined by the White man’s arrival. But America had never been an untouched wilderness. Indigenous people had been shaping (“trammeling”) these ecosystems for millennia.

The report failed to acknowledge Indigenous contributions to Whites’ cherished landscapes. Worse, it also seemed to imply that the Indigenous people were impotent—a part of the wilderness like rocks or trees, incapable of transforming it like White men. This both misread the ecological record and dehumanized Indigenous cultures. Leopold’s well-meaning but arbitrary management goal, “a vignette of primitive America,” ended up deepening the nation’s racial divides.

In 2012, the National Park Service published “Revisiting Leopold: Resource Stewardship in the National Parks” to update the Leopold Report. It didn’t specifically mention these criticisms, instead referring to changing environmental, cultural, socioeconomic and scientific conditions. This report is generally admired. But it garnered less public attention, less surprise, less controversy and less ongoing discussion. The original Leopold Report mattered because it gave its primary audience something they’d never had before.

Long-term impact

The Leopold Report proved profoundly useful to park managers. It provided them with a decision-making framework. They could point to accepted policies to justify decisions that favored nature over development, for example, or native plants over imports.

More broadly, they now had a definition of “good management.” In Steve Mather’s day, good management had seemed self-evident: build roads, improve hotel service levels, and prohibit hunting to help wildlife. By the 1960s, managers had to account for any number of constituencies: tourists, ecologists, other scientists, employees, concessionaires, politicians, wilderness advocates, hunters, RVers, cyclists, other recreationists and more.

The world had become more complex, and the discipline of management had arisen to help organizations function effectively in such a world. Leopold showed the Park Service how to apply that discipline: You set scientifically-informed goals, develop policies to achieve those goals, and choose the best methods to implement those policies.

The Leopold Report’s most important effect may have been spurring the Park Service to embrace science. Leopold showed that science wasn’t just interesting for its own sake, it was a tool to support sound management. Thus in 1967, the Park Service established an office of chief scientist, asking Leopold to fill it. Not willing to leave Berkeley and teaching, he did so only on an interim, part-time basis.

Decisions driven by science

Some of the biggest decisions in Yellowstone’s past fifty years—such as policies around wildfires, the feeding of bears and the reintroduction of wolves—have been driven by science. Specifically, they’ve been driven by the insights of newly empowered scientists within the Park Service. Today, ecological management of the Northern Range continues to be a hotly debated topic in Yellowstone, but the debates are much more scientifically informed than they were in the 1960s.

The newly scientific focus of the Park Service has shaped Wyoming history in smaller ways, too. For example, science has now established that pronghorn from Antelope Flats in Grand Teton migrate 120 miles to winter range in the Green River Basin. Fences and other barriers clogging this migration route were the reason Leopold saw so few pronghorn at Antelope Flats. In the past few decades, numerous agencies and nonprofits have spent millions of dollars protecting and restoring the “Path of the Pronghorn,” America’s first federally protected migration corridor. Ongoing developments in that protection often warrant major news headlines.

It’s a wildlife restoration success story, and among those deserving credit are scientists and their supervisors at the Park Service. They prioritized and funded research to preserve the natural conditions of Grand Teton National Park. The 1963 Leopold Report had both identified that problem and suggested the philosophical and organizational approaches to address it.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support which in part made publication of this article possible].

Resources

Primary sources

- A. Starker Leopold papers, BANC MSS 81/61 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Contains letters, diaries, project files, clippings and other material. Sources consulted for this story include:

- Leopold, A. Starker. “Preserving the Qualitative Aspects of Hunting and Fishing” Conservation News, Oct. 15, 1954, carton 6, folder 29.

- Leopold, A. Starker. “The hunter's role in wildlife conservation,” typescript, carton 11, folder 20.

- Colwell, Rita, et al. "Revisiting Leopold: resource stewardship in the national parks." National Park System Advisory Board Science Committee, Washington, DC, 2012.

- Howe, Robert E. “Final Reduction Report: 1961-62 Northern Yellowstone Elk Herd.” Yellowstone National Park, May 17, 1962, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at http://npshistory.com/publications/yell/no-elk-herd-reduction-rpt-1962.pdf.

- Good, John. “Reminiscence from the Firing Line.” Yellowstone Science 8, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 3-6, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at http://npshistory.com/publications/yell/newsletters/yellowstone-science/8-2.pdf.

- Leopold, A. Starker. Oral History. Sierra Club Oral History Project, 1984, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/roho/ucb/text/sierra_club_nationwide2.pdf, 117-174.

- _______________. “’What We’re Talking about Here are Dynamic Processes that Don’t Stop’: A Speech to the National Park Service Western Region Superintendents' Resource Management Seminar, April 28, 1975,” The George Wright Forum 30, no. 2 (2013): 202-211, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at http://www.georgewright.org/302leopold.pdf.

- Leopold, A. Starker, et. al.. “Wildlife Management in the National Parks.” March 4, 1963, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/leopold/leopold.htm.

- Zahniser, Howard. (Unsigned editorial.) “Guardians not Gardeners.” The Living Wilderness 83, spring-summer 1963, 2. See also “Leopold Report Appraised,” 20-24 in the same issue.

Secondary sources

- Carhart, Arthur Hawthorne. “Shall We Hunt in National Parks?” Sports Afield, 1961. Vertical File Collection, Yellowstone Research Library, Gardiner, Montana, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://wyld.wyldcatalog.org/Record/a889990.

- Chase, Alston. Playing God in Yellowstone. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt Brace, 1987, 31-37. See also the epilogue to the paperback edition.

- Evans, Leon. “A Summary of the History of the Yellowstone Elk Herd.” Yellowstone Nature Notes, Vol. IXV, January-February, 1939, Nos. 1-2, accessed Nov. 6, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/yell/vol16-1-2b.htm.

- Forbes, William. “Revisiting Aldo Leopold’s ‘Perfect’ Land Health: Conservation and Development in Mexico’s Rio Gavilan.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas, 2004, accessed Oct. 27, 2023 at https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc4708/m2/1/high_res_d/dissertation.pdf.

- Goldfarb, Ben. Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of our Planet. New York: W.W. Norton, 2023, 41.

- Koshmrl, Mike. “Path of the Pronghorn at ‘high risk’ of being lost, new analysis finds.” WyoFile, Nov. 3, 2023, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://wyofile.com/path-of-the-pronghorn-at-high-risk-of-being-lost-new-analysis-finds//.

- Pritchard, James A. Preserving Yellowstone's Natural Conditions: Science and the Perception of Nature. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1999, 2022, see especially Chapter 4.

- Pyne, Stephen J. “Vignettes of Primitive America: The Leopold Report and Fire Policy.” Forest History Today, Spring 2017, 12-18, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Pyne_Vignettes.pdf.

- Rydell, Carol Henrietta Leigh. “Aldo Starker Leopold: wildlife biologist and public policy maker.” M.A. thesis, Montana State University, 1993. Rydell, a former Park Service historian, is preparing a book-length biography of Leopold, which we should all look forward to.

- Sellars, Richard West. Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2009, 244-247.

- Sowards, Adam M. “The Slaughter of Elk at Yellowstone National Park.” Jstor Daily, Aug. 18, 2021, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://daily.jstor.org/the-slaughter-of-elk-at-yellowstone-national-park/.

- Smith, Jordan Fisher. Engineering Eden: The True Story of a Violent Death, a Trial, and the Fight over Controlling Nature. New York: Crown, 2016, especially 92, 290-291, 302.

- Thuermer, Angus M., Jr. “In Grand Teton, retiring biologist sees wildlife restored.” WyoFile, Jan. 27, 2015, accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://wyofile.com/grand-teton-retiring-biologist-sees-wildlife-restored/.

- United States National Park Service. “Elk: An Icon of the West.” (Population data), accessed Nov. 6, 2023 at https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/elk.htm.

- Urbigkit, Cat. Path of the Pronghorn. Honesdale, Pennsylvania: Boyds Mills Press, 2010.For children.

Illustrations

- The photos of Starker Leopold at Rio Gavilan, July 1948 and hunting in the Tremblor Mountains, November1955, are from the Aldo Leopold Archives at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Used with thanks.

- The images of the bull elk in winter in Yellowstone and the Jeff Henry image of the 1988 fires in Norris Basin are National Park Service photos. Used with thanks.

- The elk population chart is from a National Park Service publication, “Elk: an Icon of the West,” which gives lots more detail on reasons for the population’s rise and fall. Used with thanks.