- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Amalia Post, Defender of Women's Rights

Amalia Post, Defender of Women's Rights

From territorial Wyoming, Amalia Post wrote in a letter to her sister in Michigan, “I suppose you are aware that Women can hold any office in this territory. I was put on the Grand Jury. I am intending to vote this next election [which] makes Mr. Post very indignant as he thinks a Woman has no rights.” By 1870, Wyoming was the only place in the United States where women could serve on a jury or vote in a general election, so Amalia Post was announcing her intention to stand at the forefront of a revolution.

American women had been agitating for the right to vote for a long time. During the drive for American independence in the 1770s politically astute colonial women had sought to include female voting rights in the new states’ constitutions. They achieved no success. In the 1830s and 1840s, women’s participation in the political process began to increase again when activists found a rallying point in anti-slavery campaigns. Yet although the Civil War ended with universal male suffrage, females were still excluded from the polls.

Amalia Barney Simons Nichols Post was an unlikely revolutionary. Born Jan. 30, 1826, in Johnson, Vt., she was raised in the mid-19th century ideal of separate spheres. Separate spheres assumed that men and women were different but complementary in their natures. Women were passive, nurturing and domestic. Men were aggressive, competitive and better suited to work outside the home. It was the husband’s job to support and protect his wife and children. It was the wife’s job to provide her husband with a refuge from the corruption of the world in the domestic sphere. When Amalia Simons married Walker T. Nichols in Lexington, Mich., in 1855, she expected her life to follow this pattern.

Domestic life on the frontier

Life, however, did not cooperate with the ideal. Walker and Amalia Nichols left Michigan to seek financial opportunities in the then-frontier town of Omaha. After struggling to establish himself in Nebraska Territory, Walker Nichols decided that there would be better opportunities in the even more remote mining camps around Denver. He did not discuss this decision with his wife. He did not even inform her of it. “Walker has gone to the mines,” she wrote to her sister Ann. “I did not know that he was going. . .[H]e left me without any money all alone among strangers. . .but I suppose that he has done what he thought best.”

Amalia was forced to borrow money from her father so she could return to her family’s home in Michigan. In May or June of 1861 she traveled to Denver to be reunited with her husband. The town was only a little over two years old, but it had “five or six large Hotels, very large stores & some beautiful dwelling houses.” However, Amalia was shocked by the moral tone of the place, where couples could form quite casual relationships. She wrote that she didn’t know “who is married nor who is not.”

Within a year Walker Nichols had deserted his wife again, this time in the company of another woman. Amalia sought and gained a divorce. This time she did not go back to Michigan, partly because she was ashamed of her status as a divorced woman, but also because she found that she was quite able to negotiate the world of money-making and commerce on her own. She raised chickens and loaned out the money she made at interest. She formed business partnerships with men. In October 1864, she married one of these partners, Morton E. Post.

A second marriage

Morton Everel Post was born in New York in 1840—14 years after Amalia. He had relocated to Colorado Territory in 1860 and was engaged in freighting goods between the Missouri River and Denver. He was often separated from his new bride, however. In order to create a more stable home, he moved to Wyoming Territory in 1867 where he began building a store in Cheyenne in partnership with George Manning.

But the building went slowly, society in Cheyenne was “very rough” and money was unusually tight. Their reunion was put off to the following year. By summer, Morton was so discouraged with the country and the state of his business that he wrote of selling out, but Amalia was determined to end their separation. She got on the train and arrived in Cheyenne in July 1868.

By the time Amalia Post arrived in Cheyenne, she had ceased to be the retiring domestic partner prescribed by the theory of separate spheres. Even after she remarried, she retained financial independence by maintaining her property in her own name, a precaution possible to her only because of the relatively liberal married women’s property laws of Colorado and Wyoming.

First women on juries

About a year and a half later, the first territorial assembly of the newly formed Wyoming Territory--of which Cheyenne was now the capital--passed an act to grant women the right to vote and hold office. Reasons asserted by the all-male legislators for their unusual decision ranged from a desire to do justice to a desire for publicity. One legislator later alleged that the passage of the act was a joke. Certainly the act did not seriously threaten male domination of territorial politics, since Wyoming contained six men for every adult woman. Whatever the motives, Wyoming had taken a step unique in western democracies at that time.

Until the passage of the suffrage act, Amalia Post showed very little interest in voting rights, but she was soon caught up in the experiment. The first tests of women’s new civic responsibilities came before the September election. Some judges ruled that, as jurors were selected from the voter rolls, women were now eligible for jury service. Accordingly, women were called up for service on grand and petit juries in the spring of 1870 and 1871. Amalia Post was called to serve on a petit jury in 1871.

“I was Foreman of the Jury,” she wrote, “& the man was condemned & sentenced to be hung. [W]e found him guilty of murder in the first degree as found in indictment. . . .There is no fun in sitting on a jury where there is murder cases to be tried. [T]his one that is to be hung killed two.”

The brief experiment with women jurors may have been intended to discredit female suffrage. Although that did not happen, there were consequences. For one thing, according to Wyoming historian T.A. Larson, the male jurors felt inhibited about smoking and spitting inside the jury box, reducing their level of comfort. In addition, it was believed that female jurors were stricter and less inclined to accept pleas of self-defense in murder cases.

Amalia Post’s testimony would seem to support that perception. Women, it was reported, also tended to impose heavier fines. Overall, it seems the women jurors simply applied the moral values of their domestic sphere to society at large. Men, apparently, decided this was carrying the experiment too far. After 1871 the weight of judicial opinion concluded that jury service was not a requirement of suffrage after all.

National woman suffrage politics

Events soon pushed Amalia Post into becoming a leader of the women’s rights movement not only in Wyoming but nationally. In January 1871, she traveled to Washington, D.C., as a delegate from Wyoming to the annual lobbying conference of the National Woman Suffrage Association. There she conferred with such leaders of the national movement as Susan B. Anthony, Victoria Woodhull and Isabella Beecher Hooker.

“I was made more of than any other Lady in convention,” she boasted when writing to her sister. But when Mrs. Hooker pressed her to stay on and “besiege congress,” she refused. Whatever Amalia’s reasons, they had nothing to do with deference to her husband’s political opinions. Amalia Post was an active Republican, while Morton E. Post was a staunch Democrat.

Agitation for women’s rights would continue for nearly 50 years before women were granted the right to vote nationally. Opponents cited St. Paul’s biblical injunction to women to be “discreet, chaste keepers at home and obedient to their husbands.” They objected that women would sully their pure minds by thinking about politics and would endanger their weak bodies by “elbowing their way through the promiscuous crowd that collects around the ballot box.” They threatened that men would be “relegated to the domesticity of the kitchen and nursery” if women voted, and that soldiers would wear petticoats.

Defeating a repeal attempt

In the fall of 1871, the second Wyoming Territorial Legislature sent a bill to the governor to repeal women’s suffrage in the territory. Amalia Post is credited with making a personal appeal to Gov. John A. Campbell to veto the bill. She probably did make such a request, but Governor Campbell very likely would have vetoed the bill in any case.

The governor returned the bill unsigned with a multi-page message refuting in detail the arguments against women’s suffrage. He defended women’s intellectual capacity. He cited the success of the experiments with women voters and jurors. He appealed to the injustice of giving some property owners more rights than others.

Amalia Post is also credited with lobbying legislators to vote against the attempt to pass the bill over the governor’s veto. The attempt to override the governor’s veto passed the House but failed by one vote in the Council—the territorial senate. Women have retained the right to vote in Wyoming ever since.

The Posts in Cheyenne

By the mid-1870s, the Posts were well established in the top echelon of Cheyenne society. Morton Post was a leading banker and businessman. The business block which he had built at the corner of 17th and Ferguson, later Carey Avenue, housed the Wyoming Territorial Legislative Assembly in 1875. He was a Laramie County commissioner from 1870 to 1876, and in 1881 and 1885 he was elected a delegate to the United States Congress from Wyoming Territory. He was the senior partner of the banking house of Morton E. Post & Co. and maintained interests in various mercantile, sheep raising and mining ventures.

However, his extensive speculations could not shield him when Morton E. Post & Co. failed in October 1887. Bad weather and overgrazing put economic strain on many of the cattle growers to whom the bank had advanced money. The bad loans multiplied, and at last, the bank closed. Morton Post moved to Utah Territory in 1889 and to Los Angeles in 1895. He engaged in real estate and coal speculation and, later, took up farming and fruit growing.

Amalia Post and her time

Amalia Post did not accompany her husband on these later moves. Her property, which she maintained separately from her husband’s, was largely in real estate, although she also owned a flock of sheep. She remained in Cheyenne, suffering from increasingly poor health, until her death on Jan. 28, 1897. Morton Post died in Alhambra, Calif., in 1933.

Amalia was a woman of her time. She was raised in the theory of separate spheres, and appears to have accepted it. The real world, however, collided unpleasantly with this ideal. Although she deferred to her first husband’s judgment, he failed to make sound financial choices, and rather than shielding her from the world, he abandoned her to it. According to the theory that women were incompetent to engage in an individual struggle for survival, Amalia should have become a victim. She should have sunk into crime, prostitution or death.

Instead, Amalia rose. She supported herself better than her husband had done. Some of her success was due to the fact that she had been abandoned in a newly settled country where women and capital were both rare. Cultural prejudice against women engaging in business was reduced, and many men were eager to form partnerships regardless of the gender of their partner. But whatever factors assisted her, the result was that Amalia Post discovered first that she could not count on a man to protect her, and then that she did not have to. She realized how dangerous the restraints of a gender role could be, and, gradually, she became active in the campaign to change them.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Cheyenne Daily Leader, March 21, 1871.

- Amalia B. Nichols vs. Walker T. Nichols, Sept. 1, 1862. Divorce Records, Denver. Colorado State Archives.

- “Has Woman a Right to Vote?” anonymous undated manuscript. Nellie Tayloe Ross Papers, 1880s-1998, Accession Number 948, American Heritage Center [hereafter AHC], University of Wyoming.

- Morton E. Post Family Papers, 1851-1900, Accession Number 1362, AHC. (Letters of Amalia Post to her sister Ann 1860, 1861, 1870, 1871; letter of Amalia Post to her father, March 1876; and letters of Morton Post to Amalia Post, September 1867-July 1868.)

- “Woman Suffrage Message of Governor Campbell to the Legislature of Wyoming, Dec. 4, 1871.” Grace Raymond Hebard Papers, 1829-1947, Accession Number 400008, Box 40, Folder 20. AHC.

Secondary Sources

- Beach, Cora. Women of Wyoming. Casper, Wyo.: S.E. Boyer & Co., 1927, 170-172.

- Dinkin, Robert J. Before Equal Suffrage: Women in Partisan Politics from Colonial Times to 1920. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1995, 106, 120.

- Donnelly, Mabel Collins. The American Victorian Woman: The Myth and the Reality. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1986.

- Dubois, Ellen Carol. Woman Suffrage and Women’s Rights. New York, N.Y.: New York University Press, 1998.

- Imbornoni, Ann-Marie. “Women’s Rights Movement in the U.S.: Timeline of Key Events in the American Women’s Rights Movement, 1848-1920.” Infoplease.com, accessed Oct. 18, 2013, at http://www.infoplease.com/spot/womenstimeline1.html.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. 2d ed., rev. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1978, 78, 80-81, 84-85.

- Myres, Sandra L. Westering Women and the Frontier Experience 1800-1915. Albuquerque, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

- Thompson, D. Claudia. “Amalia and Annie: A Case Study in Women’s Suffrage.” Women’s History Magazine 50, (2005): 4-9.

- Thompson, D. Claudia. “Amalia and Annie: Women’s Opportunities in Cheyenne in the 1870s.” Annals of Wyoming 72, no. 3 (summer 2000): 2-9.

- Trenholm, Virginia Cole, ed. Wyoming Blue Book. Vol. 1. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Wyoming State Archives, 1974, 150, 286.

- Woods, Lawrence M. Wyoming Biographies. Worland, Wyo.: High Plains Publishing Co., 1991, 155-156.

- Zamonski, Stanley W. and Teddy Keller. The ’59er’s: Roaring Denver in the Gold Rush Days. Frederick, Colo.: Platte ’N Press, 1983.

Illustrations

- The photo of Amalia Post is from the Wyoming State Archives, and the photo of Morton Post is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Both are used with permission and thanks.

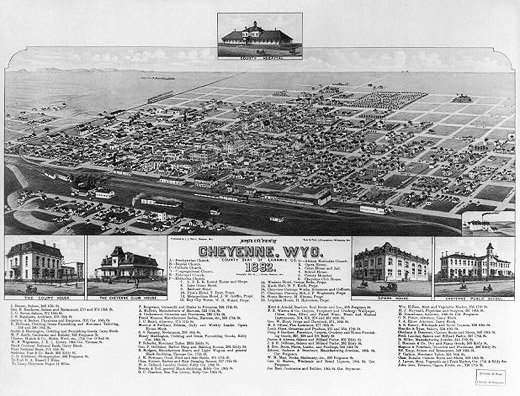

- The images of Cheyenne in 1882 and of women voting in Cheyenne in 1888 are from the Library of Congress, used with thanks.